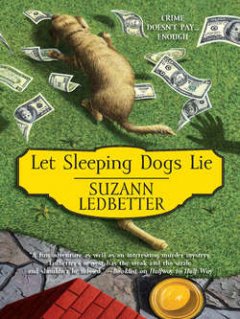

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie

Àâòîð:Suzann Ledbetter

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:367.47 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 250

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 367.47 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie

Suzann Ledbetter

Private investigator Jack McPhee has a two-word business philosophy: no partners. Rules are allegedly made to be broken, but Jack didn't expect that a contract to nab the so-called Calendar Burglar would force him to team up with a ten-pound, hyperactive Maltese. Or that as McPhee Investigations goes to the dogs, he'd fall deeply in-like with Dina Wexler, an undertall groomer, whose definition of a P.I. comes from watching w-a-a-y too many detective shows.Or that his absolutely genius idea to catch a thief would make him the prime–and only–suspect in a cold-blooded, diabolical homicide.

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie

Suzann Ledbetter

For the unsung, everyday heroes who often put their own

lives on hold to care for a loved one in need.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Once upon a time I was four feet ten inches tall, like my character, Dina Wexler. I even have vague recollections of climbing up the kitchen cabinets to plunder Mom’s stash of Brach’s milk chocolate stars and brushing my teeth with my chin hovering a skosh above the basin.

A now-five-seven adult’s memories of a time when much of the world was beyond my reach and everyone was literally looked up to weren’t enough. Huge thanks go to Veda Boyd Jones and Mary Guccione for insights on the grown-up and short-statureds’ daily frustrations and creative adaptations and the fact that larger than life has everything to do with heart and nothing to do with height. I am in their debt and stand forever in their shade.

Thanks also to John Bragdon, consumer assistant at Jacuzzi, Inc., in Dallas, Texas, for product information critical to my homicide scenario. Darrell L. Moore, Greene County (Missouri) Prosecuting Attorney, keeps the legalities straight and factual, and lets me pick up the lunch tab once in a while. Pat LoBrutto, dear friend and opera buff, filled in on the finer points of Pagliacci and sang a few bars of an aria on the phone. Without Jean Edwards, Comair customer service representative at the Springfield-Branson (Missouri) Regional Airport, I’d have flubbed my plot-oriented flight plans six ways of Sunday. The mythical Park City, Missouri, has several more connections elsewhere than available in fact, but the beauty of fiction is getting the basics right and taking it from there.

Lara Hyde and Mary-Margaret Scrimger at MIRA Books were excellent, devoted editorial glitch finders; any remaining are mine. A hearty salute also to Robin Rue, Writers House, LLC, for the past twentysomething books. Thank you, team. You rock.

As does Dave Ellingsworth. One day, maybe I’ll find the words to tell him how lucky I am to be his wife, best friend and forever partner in real life.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

1

“Aw, c’mon, Cherise. Be reasonable.” Jack McPhee’s lips pulled back in a grimace. The heel of the hand not holding the telephone receiver clunked his temple. Too little, as recriminations went, and definitely a couple of words too late.

“Be reasonable” was number nineteen on the list of sixty-two things to never say to a woman. Any woman, whether you were dating her, sleeping with her, married to her, called her Mom or she knew “the usual” was Chivas on the rocks with a twist.

Therefore, it was hardly a surprise when Cherise Taylor’s normally dulcet drawl could have etched granite. “So,” she said, “it’s unreasonable for me to be upset about being stood up for dinner. Again.”

“No, no, of course it isn’t,” Jack said, tired of reciting dialogue from a familiar script and the revolving cast of leading ladies. Any second now, she’d say…

“We haven’t seen each other since Thursday at lunch.”

“When I told you I had an out-of-town job to take care of.” An off-the-books, expenses-only one for a friend, Jack might have added, but what was the point?

“Yeah, and I stayed home all weekend, in case you called.” A derisive snort, then a plaintive, “You’ve heard about floors clean enough to eat off of? You could take out somebody’s spleen on mine.”

Jack tapped a pencil end over end on the desk blotter. He’d flown to Seattle by way of Dallas and Denver, logged twelve hours’ sleep in seventy-two and the majority of those after he fell into his own bed last night. “If I’d had a chance to call,” he said, “and you weren’t home, I’d have tried your cell phone. If you didn’t answer, I’d have left a voice mail.”

“Oh? Then it’s my fault I was bored out of my mind all weekend.”

Pretty much, he thought. A bit harsh, maybe, but before he came along, Cherise volunteered on Saturdays at a library teaching English as a second language. Sundays, she’d meet her married sisters for a girls’-day-out brunch, then hit the flea markets, catch a chick flick or zip north to Kansas City to shop at malls identical to those in Park City.

Sniffling now, Cherise went on, “And you don’t even remember what day this is, do you?”

The obvious trick question disqualified Monday as the correct answer. Jack’s eyes cut to his page-a-day calendar. July 7 was blank, apart from a sticky note to remind him to drop his suit at the cleaners before the bloodstains set.

“Who cares if tonight’s our anniversary?” Sniff-sniffle. “No big deal.”

Jack pulled away the receiver, examining the sound holes as if the pattern would reveal what the hell she was talking about. Anniversaries commemorated wars, major battles, natural and unnatural disasters and wedding ceremonies. None of those applied, yet all of a sudden, the commonality seemed oddly significant.

“For six months, I’ve put up with your weird hours. With dates canceled at the last minute and knowing your mind’s anywhere but on me sometimes when we are together. But have I complained? Uh-uh. Not even once.”

I wish you had, Jack thought. Repeatedly and often.

On a shelf above the microwave at his apartment was a framed sampler that read: “The lower the expectations, the higher the probability a man will tunnel under them.” His ex-wife had cross-stitched it and given it to him for a divorce present. Whether she’d coined the phrase, or copped it from Gloria Steinem, a louse with good intentions should have it tattooed on his forehead.

“I’m sorry, Cherise,” he said. “I really am.”

A lengthy silence acknowledged the subtext. “Me, too.” Cherise’s sigh implied a middle-distance stare at the ceiling, select memories scrolling behind her eyes, her head shaking in futility. The image skewed somewhat at her muttered, “Honesty in a relationship, my ass.”

Jack scowled. “Hey, now wait a sec. I have been honest with you. A hundred percent from the first time we went out.”

“Sure you were,” she agreed. “But how was I supposed to know that?”

His mouth fell open. Bereft of an intelligible response, he raked his fingers through his hair and wondered if a lapsed Episcopalian was eligible for the priesthood.

“First date,” she said. “Between the beer course and the pizza, I asked you to describe the perfect woman. I expected the usual answers—Julia Roberts, Angelina Jolie, Salma Hayek. If you’d said your mother, I wouldn’t have stuck around for the cinnamon bread.”

Jack could do worse than a gal like the one who’d married dear old Dad. And had more times than he cared to count. “For the record, my mom’s a wonderful woman, but not exactly my type.”

“I gathered that when you said ‘The perfect woman for any man doesn’t confuse supportive with taking his crap and making excuses for him.’” Cherise laughed. “Ten points for creativity, but you really didn’t expect me to believe it, did you?”

Actually, he had. For one, it was the truth. Plain, simple, straightforward. For another…

He didn’t have another. Couldn’t imagine why he’d need it. “Look, I—”

“Don’t, okay? Let’s leave it at we had fun, it’s over, no hard feelings, time to move on.” Cherise hesitated a moment, her voice somber, the drawl more pronounced. “I’m gonna miss you, though.”

Jack nodded, as if she were seated across the desk, not downtown in a triwalled cubicle with less square footage than a municipal jail cell. “Same here, kid,” he said, curbing the impulse to suggest a fresh start.

Barring dual amnesia, there was no such thing as a mulligan in a relationship. Jack’s crazy uncle George once owned a beater Oldsmobile that wouldn’t shift out of Reverse, but for most people, going backward to go forward was a dumb idea.

Cherise knew that as well as he did. “Let’s leave it” was code for “Goodbyes hurt, but we aren’t in love and in like isn’t enough for the long haul.” Still, the handset’s glowing redial button dared Jack to ask her forgiveness. To give him a second chance at being the dependable, thoughtful guy she deserved.

Uh-huh. Sure. He docked the phone. And while he was at it, he’d learn Parsi, buy season tickets to the opera and take up water polo.

By noon, Park City Florist would have delivered the half-dozen pink carnations Jack sent to Cherise’s cubicle. Figuring she’d understand the quantity, but not the symbolism in their color, he’d asked the clerk to write “I’ll never forget you” on the card. Although sincere, his latest failed romance was the last thing on his mind as he cruised by the Midwest Inn’s guest entrance.

The three-story, stucco-clad motel was situated on a backfilled knoll facing I-44’s prime business interchange. From the air, the building was shaped like a capital M with a swimming pool puddled between its legs. Tourists seldom traveled through southwest Missouri in helicopters, so the snazzy architecture was wasted on pigeons, drive-time traffic reporters and the local hang gliders’ club.

The all but deserted rear parking lot angled in concert with the M’s ascender points. Jack knew the checkout time was 11:00 a.m., and check-ins were prohibited before 3:00 p.m. The black Lexus sedan and a forest-green minivan parked several discretionary spaces apart credenced the adage about rules being made to be broken. Or at least bent, in exchange for the folded fifty-dollar bills Jack had slipped to the desk clerk. Two President Grants was the agreed-upon bribe for the clerk to call Jack’s cell phone with Mr. and Mrs. Smith’s room number and precise location.

He pulled in beside the Lexus and lowered his side window. It was risky to forgo tailing his quarry to the motel, but he sensed he’d been spotted at last Friday’s rendezvous at a Best Western across town. The rapid metallic ticks emanating from the Lexus’s engine confirmed the greedy desk clerk’s ETA.

Shifting his aging Taurus into Park, Jack left the engine running and snagged an equipment case from the backseat. While the building’s height shaded the asphalt for a few yards behind his car, air-conditioning wasn’t optional when midday temperatures flirted with the century mark.

He snapped photos of both vehicles with a still camera, then switched to a digital. Elbows propped on the steering wheel, he aimed the telephoto lens at room 266’s plate-glass window and adjusted the zoom.

The miniblinds were closed, as always, with the slats tilted down, rather than up. From Jack’s or anyone else’s ground-level vantage point, the interior view was akin to lurking at the bottom of a stairway to peek up a lady’s skirt.

Motels and hotels provide drapes for a reason, and it wasn’t just to give the bedspreads something to match. If married couples hot for a nooner with someone other than a spouse knew how the law defined an expectation of privacy, Jack would have to find another line of work.

Domestics weren’t his specialty. Maximum sleaze factor and aggravation—minimum challenge. But it’d been a slow summer and a guy’s just gotta do what a guy’s gotta do to cover the rent. Whether Cherise believed his excuse for canceling their date tonight or not, Jack hadn’t lied about meeting a client for dinner. Hopefully there wouldn’t be a scene, until after he’d polished off his steak and steamed veggies. Either way, he’d leave the restaurant with a check in his pocket and craving a long shower.

A couple more shots of the lovebirds’ striptease were all Jack needed and all he could stomach. The camera was whining its second electronic high C when the Taurus’s passenger door swung open. The young man tilted the whole car as he crammed himself into the seat. “Mr. McPhee,” he said, huffing a bit from the exertion. “This is your lucky day.”

A fleshy inner tube oozed from under his rock-band T-shirt and spilled over the waistband of his jeans. He smelled like a deep-fried Esquire cologne sample. Two days’ growth of stubble fanned from a goatee and bristled his chins. A ham-sized knee, then the other, wedged against the glove compartment. The .38 Police Special inside might as well have been in a bank vault in Wisconsin.

Then again, if Moby Dick was a carjacker, he’d need the Jaws of Life to stuff that gut behind the steering wheel. Jack eyed a manila folder clutched in the man’s fist. A process server would have shoved a subpoena at him and waddled off. There’d be balloons and a camera crew if the dude was with that magazine outfit’s prize patrol. Besides, you had to enter to win.

“Who the hell are you?”

“Brett Dean Blankenship.” He offered his hand. Jack didn’t take it. Nonplussed, he went on, “Pleasure to meet you, sir, but who you are is why I’m here.”

A smirk exposed teeth not many years removed from orthodontic appliances. Attention turning to the folder, Blankenship recited, “You’ll be forty-one on October 4. Married once, divorced, no kids—” he glanced sideward and heh-hehed “—as far as known. You’ve got a B.S. in criminal justice, graduated from the Park City Police Academy, then resigned two years later. You bounced around from rent-a-cop to long-haul trucking, dabbled in auto repair, retail sales and telemarketing. For the past fifteen years, you’ve been a marginally successful private investigator.”

Jack took exception to “marginally successful.” He’d had many a good year and a fair share of great ones. Self-employment ordained lean ones proportional to sweet ones. It kept you humble and out there hustling. Or it should.

“Not too shabby for a one-man operation.” Blankenship handed over three sheets of paper. “But it’s safe to say, you ain’t setting the world on fire.”

The pages’ bulleted lines noted Jack’s Social Security number, previous and current home and office addresses, savings and checking account balances, registration info on the Taurus and his pickup, average utility bills at his office and apartment…Junior G-man stuff either in public records or easily obtainable if you knew where to look.

What raised Jack’s hackles was an account of his activities over the past week. Blankenship had tailed him and Jack hadn’t even noticed. Which explained the Lexus driver’s sudden hinkiness last Friday.

He balled the sheets and tossed them into the backseat. “Whatever your game is, sport, I’m not playing. Now get outa my car, before you void the warranty on the shock absorbers.”

Blankenship blanched, then exhaled, as though a lung had collapsed. “I worked like a dog on that report. I thought you’d be impressed.” He stretched a shirtsleeve to mop the sweat trickling down his muttonchops. “The correspondence school instructor said that showing we can run background checks is the best r?sum? we can have.”

God deliver Jack from schmucks with matchbook private-detective-school diplomas. And from the Missouri law mandating a year’s apprenticeship with a licensed investigator. That and a written exam weeded out the wanna-be overnight Sam Spades, but presented certain liability issues. Like mentorship being a pain in the butt for a working, marginally successful P.I.

“I live with my mom, so I can work for free,” Blankenship wheedled. “Double the manpower, double your billable hours. Maybe triple ’em.”

Halve them was more like it. Jack needed Baby Huey under his wing like a duck needs a concrete flak jacket. “Sorry, but like you said, McPhee Investigations is a one-man agency.”

“It wasn’t when it was Gregory, Aimes & Watkins.” Blankenship shrugged. “Okay, so Watkins was dead and Aimes’s wheel was throwing spokes before Chuck Gregory took you on. If it hadn’t been for him, you wouldn’t have a license, much less your name painted on the window.”

With uncustomary patience, Jack said, “I was in the right place at the right time.” His inflection relayed as opposed to you. “Chuck wanted to retire and he loved showing rookies the ropes. Me, I’d rather hang myself with them.”

Desperation edged Blankenship’s laugh. “Come on, gimme a thirty-day trial. If it doesn’t work out, no hard feelings. At least I’ll have a month’s experience to add to my r?sum?.”

Jack’s eyes rose to room 266’s window, then lowered to the dashboard clock. By the time Blankenship extricated himself from the passenger’s seat, Mr. and Mrs. Smith could waltz out arm in arm from the building’s rear entrance.

He’d also bet McPhee Investigations hadn’t topped Blankenship’s list of employment prospects. The Park City telephone directory’s business pages advertised about two dozen agencies, including a pricey nationally franchised outfit. If the kid had a brain, he’d started there and worked his way down.

“What I will do,” Jack said, stashing the camera equipment on the floorboard, “is give you some friendly advice, while I drive you around front to your vehicle.”

“It isn’t here.” Blankenship yanked on the shoulder harness. “I took a cab so I wouldn’t blow your surveillance.”

Well, well. That hiked Jack’s previous estimation a few notches. Not enough to hire him, but maybe the kid had a brighter future than he thought. Wheeling around the motel’s east side, he said, “Where to?”

“1010 West Danbury.”

Jack gripped the steering wheel tighter—1010 West Danbury was his office address.

“I can’t wait to show you what I can do with a computer. The background check on you? Just a warm-up.” Blankenship played an air-piano solo. “Finger exercise.”

Jack reconsidered a long-held supposition about predestination. To wit, days that started off swell were fated to free-fall into the toilet. Conversely, days beginning with a cosmic swirly would inevitably improve—though the increments ranged from microscopic to worthy of a parade with lots of tubas, bass drums and scantily clad majorettes.

So far, this one was a crapper with an automatic flush.

He didn’t need a computer geek. A trusted subcontractor provided information above and beyond Jack’s expertise or time constraints. Much as he sort of admired Blankenship’s chutzpah, he’d sabotaged his fledging career from the get-go. Ditto, no doubt, at every other agency in town. Giving him the hows and whys wasn’t Jack’s purview, but if the kid listened, he might wise up.

“You’d do about anything to score an apprenticeship,” he said.

“Yes, sir.” Blankenship grinned. “As long as it’s legal.” The latter inferred illegal activities weren’t off the table, depending on the likelihood of police involvement.

“Then make a list of everything you’ve done to impress me, then do the opposite when you apply somewhere else.” Jack braked for a traffic light. “Starting with your wardrobe.”

Blankenship looked down, thoroughly bewildered. “I paid a bundle for this shirt at a Sister Hazel concert. It’s a collector’s item.”

“Frame it and hang it on the wall. The grungy jeans and tennis shoes? Garbage.” Jack adjusted his tie, a maroon silk with understated silver threads. “You want to be a professional, dress like one. Buy a razor and get a haircut. Want to work at a car wash? You’re all set.”

“Easy for you to say. Got any idea how much clothes cost when you’re my size?”

“So drop a hundred pounds.” Jack reassessed the belly garroted by the lap belt. “Make it a hundred and a quarter. Big as you are, one foot pursuit and you’re DOA from a massive coronary.”

Blankenship’s face flushed beet red. “Sure, I’m a little overweight, but I was born with a really slow metabolism and—”

Jack plucked two sesame seeds from his chin whiskers. “How many Big Macs did you slam for lunch?”

“Three, but—”

“Large fries?”

“Yeah, but—”

“Here’s a guess. You chased it down with a diet soda.”

A horn honked behind them. Jack accelerated a half block, then joined the queue in the left-turn lane. “This is America, kid. Eat whatever you want, whenever you want, but find a desk job. Investigating’s too physical for a guy your size.”

He hooked a right off First Street onto West Danbury. “Voice of experience. I stacked on seventy, eighty pounds driving a truck. Losing it was a bitch, but eating half as much, half as often did the trick. To put some distance between you and the fridge, sign up for some college courses—psychology, criminology, basic photography, Finance 101. Computers are fantastic, but not the be-all, end-all.”

Another stoplight allowed a sidelong look. Blankenship glared out the windshield, as if picturing Jack’s entrails smeared like a dead june bug’s.

“You think I’m an asshole,” Jack said. “Fair enough. I’ll stake tomorrow’s lunch money that I’m also the first one who’s taken the time to tell you what you’re doing wrong. Which is just about everything.”

He ignored the tacit “Go fuck yourself” radiating from the passenger’s seat. “Don’t ambush a prospective employer when he’s working. Don’t background-check him, either. It screams zero scruples about running anybody and everybody through the mill just because you can.”

The seat belt latch clicked open. Blankenship pushed himself through the door with considerably more grace and speed than he’d entered.

Jack called, “Hey, I’m just trying to—” a slam juddered the window glass, then reverberated through the chassis “—help,” he finished, watching Blankenship jaywalk around an adjacent delivery truck.

Gee, that went well, he thought. Evidently honesty really wasn’t always the best policy. It had, however, shored up the contention that mentoring wasn’t one of his specialties.

On the other hand, the kid’s eight-block hoof to his car wouldn’t hurt him. Maybe allow pause for thought, not to mention counteract his six-thousand-calorie lunch. Or would, if Blankenship didn’t salve a wounded ego with a banana split at the diner next door to Jack’s office.

The pedestrian crossing light flashed “Hurry up or die.” Blankenship materialized in the intersection, seemingly oblivious to the warning and the vehicle cranking a last-minute turn on yellow. The car’s tires whinnied on the pavement; its driver saluted Blankenship with an extended middle finger.

The kid didn’t notice. Didn’t flinch when the car gunned past him, fortunate the side mirror didn’t pick his pocket as it roared by. Still walking, closing the distance to the curb, Blankenship’s eyes locked on Jack. His head turned, then tipped slightly forward when his neck craned too far for comfort.

His unblinking stare didn’t project anger, defiance, disdain or the type of pity bestowed on those who’ve cast aside a golden opportunity.

Stone-cold hate, Jack said to himself. And a promise to make good on it. He looked away, confused and a little unnerved by its intensity. Keeping his own expression impassive, he glided forward with traffic.

He put a block, then another behind him. And couldn’t shake the feeling that Brett Dean Blankenship still had him in the crosshairs.

2

Dina Wexler dropped the box of macaroni and cheese on the counter and shut the cupboard door. She stepped down from the wooden stool, then side-kicked it in front of the refrigerator.

Someday she’d have a kitchen where all the food, especially junk food, lived on her level. For her, using drawers as ladder rungs to reach the cereal and a bowl to put it in was a climbing stage you never outgrew. Not when you’d stopped at four feet ten.

Count your blessings, she reminded herself. Like the man who complained about having no shoes, until he met the man who had no…

The TV in the living room went mute. “Di-na,” her mother called. “When you get a minute, would you bring me the TV Guide? I left it in the bedroom and there’s a show on at four o’clock I want to watch. For the life of me, I can’t remember what channel it’s on.”

Dina grabbed the potato chip bag off the top of the fridge. The crackling cellophane mocked her frazzled nerves. She rested her forehead on the freezer door’s cool metal face. It was only one-thirty, for God’s sake. Lunch was a half hour late, as were her mother’s medications that must be taken with meals.

In the hallway, a fabric mountain of laundry banked the utility closet’s bifold doors. The yard needed mowing. Both bathrooms were a mess. The kitchen floor hadn’t been mopped in recent memory.

Breathe in, Dina thought, breathe out. Make yourself one with the refrigerator. Better yet, be the refrigerator and chill the hell out.

The mental image of herself standing on a kid’s alphabet step stool getting Zen with a major appliance brought a whisper of a smile. No wonder Peanuts had always been her favorite comic strip. Charlie Brown refocused his chi with his head against the wall. She bonded with freezer compartments.

“Sweetheart?” her mother called, concern in her voice. “Are you all right?”

“Sure, Mom.” Dina sighed and stepped down on the ugly starburst linoleum. “Everything’s fine.”

A Park City car dealer’s commercial now wending from the living room reinforced their unspoken bargain. Harriet Wexler could keep pretending that her daughter was a human Rock of Gibraltar; Dina wouldn’t let her mother see it was a prop made of chicken wire and papier-m?ch?.

She put a saucepan of water on to boil, then spread some diet saltines with sugar-free peanut butter. Laying them on a saucer, she sidled past the early-American dinette set and into the living room.

The vacant midcentury modern duplex had seemed open and airy when Dina toured it with the landlord. The narrow galley kitchen dead-ended at a window painted shut a couple of decades ago, but the dining area’s merger with the living room gave an illusion of spaciousness. Off the hallway was a full bath, a small bedroom and the larger master with a private three-quarter bath.

A security deposit and two months’ rent had been scraped together in advance, and then there’d been furniture. Truckloads of Harriet’s dog-ugly, alleged heirlooms that Dina and her younger brother wouldn’t wish on a homeless shelter. Their mother’s insistence that her circa-1978 pine-and-Herculon-plaid home furnishings would go retro any day was attributed to the side effects of digitalis.

Dina pushed back the tide of prescription bottles, moistening swabs, tissues and assorted medical paraphernalia to make room for the saucer on the metal TV tray beside Harriet’s glider rocker. On the opposite side, another tray table held a cordless phone, paperbacks, a water glass, a dish of sugarless candy, the current crochet project and the queen’s scepter, otherwise known as the remote.

The cushioned ottoman supporting Harriet’s feet was surrounded by a paper trash sack, a tripod cane, bags of yarn, her purse, a discarded pillow and a mismatched pair of terrycloth slippers.

“Gosh, Your Majesty,” Dina teased. “The throne’s getting kinda crowded, isn’t it?”

Harriet made a face, then pointed at the crackers. “I thought you bought bread at the store yesterday.”

“I did.” Dina peered into the plastic drinking glass—half full. “I’m working on lunch, but you need to take your pills.”

“I can wait.”

Dina knuckled a hip. “So can I.” The water began to bubble on the stove. She pondered the tardy renter’s insurance premium and what effect a semi-accidental kitchen fire might have on their coverage.

Harriet nibbled a corner off a cracker. Nose wrinkling, she plinked it back on the saucer. “It’s stale.”

Petulance was as wasted as the coral lipstick she swiped on to disguise her mouth’s bluish tinge. “No, it isn’t,” Dina said. “I just opened a fresh box.”

She hadn’t, but it wouldn’t matter if elves had just carted them over from the magic bakery tree. The issue was that her mother couldn’t be trusted to take her meds unsupervised. Harriet’s newest shell game was removing the pills from their bottles and stashing them in her bra, the way Dina had palmed brussels sprouts at the dinner table and hidden them in her socks.

Harriet Wexler wasn’t senile. A bizarre sense of empowerment derived from outfoxing a caregiver she’d given birth to thirty-two years ago. On some levels, Dina understood and sympathized. On most, the pharmaceutical roulette drove her nuts.

Her mother glowered up at her, snapped a cracker in half, then shoved the whole thing into her mouth. “There,” she mumbled around it. “Are you happy now?”

“One more, and I will be.” Dina shook the appropriate pills from their amber bottles. The cost of each equaled a month’s rent and utilities. “Clean your plate and I’ll applaud.”

Sips of water, fake choking, a bit of breast-beating and voil?, the medicine went down. “I hope you’re proud of yourself, Dina Jeanne. You’re nothing but a bully.”

Dina recited in unison, “Thank heaven your father isn’t alive to see how you treat your poor old sick mother.” Leaning over, she kissed a prematurely white head that smelled of waterless shampoo and hairspray. “Daddy’s definitely rolling in his grave knowing I’ll bring your lunch, test your blood sugar, hook up the nebulizer, change your sheets, tuck you in for a nap, do the laundry, fix a snack, give you a shot, poke down three more pills, walk you twenty-five laps up and down the hall, then start dinner.”

As she straightened, her mother’s never warm fingers circled her wrist. “Oh, sweetheart, I’m so sorry.” Tears glistened in eyes once as blue as a summer sky. “I don’t know why I say such awful things to you.”

Because now I’m the parent and you’re the child and you hate needing the snot-nosed kid you potty-trained to help you to and from the bathroom sometimes.

“It’s okay, Mom.” Dina swallowed audibly, then cleared her throat to mask it. Aged ears dulled to soap opera dialogue and the radio remain subsonically attuned to the slightest emotional nuance. “Besides—” she forced out a chuckle “—when have I ever listened to a word you say?”

“Humph. If you ever did, you never let on.” Harriet plucked at the sheet draping her legs, as though the air conditioner was set at sixty-two instead of eighty-two. “I thought Earl Wexler was the stubbornnest critter that ever walked on two legs. You bested him from the day you were born.”

Dina tapped her toe, waiting for the upshot. It came right on cue. “I don’t know what I’d have done if Randy hadn’t been such a happy, sweet-natured little fella. Hasn’t changed a bit, either, in spite of all the disappointment and heartache he’s suffered.”

“Uh-huh.” Dina turned and started for the kitchen. “Life doesn’t get any tougher than playing drums for a wanna-be rock band for ten freakin’ years.”

Her younger brother was everything she wasn’t: tall, blond, charming, funny, gifted and as irresponsible as a golden retriever puppy. Harriet outwardly adored the child who’d needed it more, thinking the daughter who denied being anything like her would be stronger for being pushed away. Earl Wexler had spoiled Dina, loved Randy inwardly and didn’t notice which child never laughed at his joke about the hospital switching Randy with his real son.

Politics isn’t just local or exclusive to public office. Before children can feed themselves, instinct discerns the balance of power and how to work it. The Wexlers’ parental duopoly should have triggered sibling rivalry on a biblical scale. Rather than fight each other, Dina and Randy had joined forces to sandbag the adults.

And the little shit still is, she thought. Except now I’m the adult, I’m flying solo and it sucks. Drummer Boy’s sporadic twenty-five or fifty-dollar money orders mailed from towns Dina had to squint to locate in an atlas were so not like being here.

The doorbell rang, startling her. The prodigal’s return? Dina glanced around, as though a Lifetime channel camera crew might have sneaked in when she wasn’t looking. Torn between water spitting on the stove burners and rescue fantasies, Dina threw open the door. “Randy, oh my—”

The two men on the stoop recoiled. The shorter one retreated to the concrete walk. Feeling her face flush scarlet, Dina stammered, “Th-thanks anyway, but we don’t need to be saved. We’re Jewish. Orthodox.”

She used to tell roving God squads they were Catholic, but some well-meaning missionaries took it as a challenge. While Dina’s knowledge of Judaism was gleaned from Seinfeld reruns, the tack had effectively decimated any hope of conversion.

“Are you Mrs. Wexler?” the taller man inquired. He consulted the clipboard in the crook of his arm. “Mrs. Harriet Wexler?”

Dina eyed the medical-supply-company insignia above his shirt pocket. The doctor-prescribed oxygen machine was scheduled for delivery on Monday, July 11, between 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. This, however, was Sunday. The tenth. She was absolutely almost certain of it.

Thinking back to the previous evening for confirmation, she realized that it had been Sunday, therefore this was Monday and a good chunk of it was gone. Small comfort, knowing time warps were the purview of mothers with young children and the housebound by choice.

Behind her, Harriet inquired, “Is that the Avon lady? Get me a bottle of that lotion I like. A big one. That skimpy thing you bought before didn’t last a month.”

The deliverymen—both named Bob, by their lanyards’ photo IDs—gave Dina the tight smiles she’d dubbed “Oh, but for the grace of God go I.” They probably had sisters to tend the sick, too.

Dina let them in, then excused herself to ward off a kitchen disaster. Leaving the nearly dry saucepan in the sink to cool, she wiped peanut butter across a few more crackers, poured her mother a glass of milk and grabbed a banana.

A diabetic diet’s food exchanges and substitutions weren’t that complicated. Meal timing was as crucial as the menu. The object was balancing calories and carbs to maintain blood-sugar levels. Lunch included a vegetable serving, as well, but it’d be a miracle if Harriet ate a bite of anything.

Dina returned to the living room as her mother was saying, “Y’ all go on about your business and leave me be. I signed a paper way back saying I don’t want a machine breathing for me.”

“That’s a ventilator, Mom.” Dina’s elbow evicted the tissue box to make room for the milk and fruit on the tray table. “They brought the oxygen machine Dr. Greenspan ordered to lessen the strain on your heart.”

The cardiologist had also scripted a portable tank to trundle along when Harriet left the house. Which she didn’t, other than for doctors’ appointments and lab tests. Harriet had nodded amiably during Greenspan’s treatise on blood oxygenation, simultaneously blocking out parts she chose not to hear.

“But there’s nothing wrong with my heart.” Her mother stuck out a bony wrist. “Feel that pulse. Strong as an ox, I tell you.”

Everything was wrong with her heart, but Dina replied, “And the doctor wants you on oxygen full-time to keep it that way.” She waved the men toward the hallway. “So while you finish lunch, Bob and Bob and I will move enough furniture in here to make room for the machine.”

“Oh, no you won’t.”

The Bobs halted midstride.

“I’ll go to a nursing home before you’ll shut me up back there all by my lonesome.”

“Mom, please. Don’t fight me on—”

“What in Sam Hill am I s’posed to do all day? Time and again, I asked you for a cable gizmo in my room.” Harriet grabbed the remote and clasped it to her bosom. “Stick that machine on the roof for all I care. I ain’t budgin’ from this chair till the undertaker peels me out of it.”

Dina scrunched her hair in a wad, battling the urge to scream. To run out the goddamn door. To call the constant bluff and pack her demanding brat of a mother off to whatever nursing home would have her.

She hadn’t given the TV a second thought. Why, she couldn’t fathom, other than life-sustaining oxygen taking priority over Golden Girls reruns. The excuse for a single cable outlet was that Harriet needed rest and wouldn’t, with a TV blaring in her room all night. In truth, Dina couldn’t afford the extra installation fee or monthly charges.

“Uh, ma’am?” Taller Bob said. “We can—”

“It’s not a problem, really.” Dina’s arm dropped to her side. “Don’t worry, Mom. You’ll have your TV. Everybody just relax and give me a minute to think.”

She crossed to the patio door on the far side of the room and looked back to the dining area. Taking stock and mental measurements, she said, “Okay. What we’ll do is shove the couch around over there, then move Mom’s bed in here. The oxygen machine can go between it and her chair. Easy access, whether she’s lying down or sitting up.”

Tall Bob and Other Bob exchanged weary, all-in-a-day’s-work looks. Like carpet cleaners, home-health-care equipment employees’ job descriptions entailed a lot of heavy lifting.

Wait till they got a load of—literally—Harriet’s monster, dark-stained pine cannonball bed. And the matching hutch-top dresser and highboy they’d have to finesse the mattress and box springs past without disturbing a jillion dusty knicknacks and framed photographs.

Harriet whipped back the sheet. Pushing upright, she grabbed her cane and hobbled off down the hall. Dina guessed she wanted to hide the personal, even intimate items that age and illness remanded to plain sight on the nightstand.

Dina continued, “The coffee table, end tables, bookcases—crap in general—we’ll dump in Mom’s room.” To herself, she added, And when Mom isn’t looking, I’ll sneak Randy’s crap out of the second bedroom in there, too.

Thumps in the hall preceded Harriet’s reappearance. Clutched in a quaking, blue-veined fist was Earl Wexler’s long-barreled revolver. “You boys lay one hand on my things and I’ll blow it clean off.” Her glare and the gun wobbled to Dina. “That goes for you, too, missy. I’m not an invalid like your daddy was. I’ll be damned if you’ll make me into one.”

Having lost the argument about pawning the gun, Dina had removed the bullets on the sly. The garbage seemed the obvious disposal method, until she pictured city sanitary landfill workers running from a hail of exploding shells. Safer, she decided, to bury them in the backyard.

A subtle head shake informed the Bobs that the revolver wasn’t loaded. Evidently aware of the number of people who die every year from “unloaded” guns, both men faded back behind the TV stand.

“Of course you aren’t an invalid, Mom.” Dina eased toward her. “Far from it. But if the TV has to stay where it is, it only makes sense to bring you to it.”

“Loll around where everybody that comes to the door can see me.” Harriet snorted in disgust. “Why, I’d sooner plunk myself in Penney’s front window at the mall.”

Dina removed the heavy revolver from her mother’s hand before she dropped it and broke a foot. Staring down at it, she remembered her father making the same Penney’s window remark to a hospice volunteer. She should have known that for his widow, setting up a bed of any kind in the living room was a death knell. A small, terrifying step away from the hospital type brought in for Earl Wexler’s final months.

That time would inevitably come again. A year from now, two, five—the doctors were continually astonished by Harriet’s resiliency. When they remarked on it, she always said, “The secret to livin’s being too mean to die. God don’t want you and the devil’s scared of what you’ll do if he gets ya.”

Dina laid the gun on the dining room table, then faced her mother. “I understand about the bed. I don’t have the money to put cable in your room. Dr. Greenspan wanted you on oxygen weeks ago, but you had to get sicker before Medicare would pay for it. Telling me you won’t do this and I can’t do that isn’t getting the machine in here, where you can use it.”

She turned to Bob and Bob. “Which these very patient, very kind men will put wherever they think best.” She smiled at them, adding, “I’m not passing the buck.” A shrug, then, “Okay, I am, but now that I’ve royally screwed up and pissed off Bonnie Parker in the process, you’re in charge.”

Harriet grunted. “They should’ve been in the first place.”

“I know.” Dina cupped her elbow to guide her back to the throne. “I ought to be horsewhipped for trying too hard to make you happy.”

“You’re nothing but a bully, Dina Jeanne.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And you’re gonna be sorry when I’m gone. I’m changing my will. Randy gets everything. Lock, stock and barrel.”

Dina steadied her for the awkward, off-balance descent into the chair. Her mother’s shallow, raspy breathing scared her. A glance over her shoulder at Taller Bob telegraphed, “Hurry. Please.”

3

Jack McPhee eyed the redhead striding into Ruby Tuesday’s dining area. So did every man at the bar and seated at tables. Their female companions’ heads turned, following their gazes, curious why conversations halted in midsentence or lunch dates suddenly forgot how to chew. To a woman, the object of such dumbstruck attention fostered death-ray glares.

Belle deHaven always had that effect on people. A teal silk, hourglass-tailored sheath contributed to it. So did an impeccable pair of mile-long legs, a flawless complexion and green sloe eyes. But it was the inner, indescribable something she projected that deeded the room to her.

Jack stood and pulled out the adjacent chair. “You’re late, as usual.” Belle kissed his cheek, then scrubbed off the evidence with her thumb. “After all these years, you’d be crushed if I was on time.”

“The shock might be fatal.”

Laughing, she sank into the chair and laid her clutch purse on the table. “Careful, McPhee. I know CPR, and it might be fun getting you in a lip lock again.” Belle hoisted the cosmopolitan he’d ordered for her and took a sip. “You were a lousy husband, but a world-class kisser.”

“Oh, yeah?” Jack cocked an eyebrow. “Sounds like my replacement could use a couple of pointers.”

“Dream on, hon. Carleton is everything I ever wanted. Smart, handsome, respectable—”

“Rich.”

Belle shrugged. “That, too, but money really doesn’t buy happiness.”

You’re just now figuring that out? Jack thought.

She drank again and sighed. “Poverty wasn’t as romantic as it’s cracked up to be, either.”

“It’s not like we starved. It just took me a while to figure out what I wanted to be when I grew up.”

“As if…” Four tapered, manicured fingers grazed his jacket sleeve. A squinted visual inspection elicited a gasp. “Armani? Good God, Jack. Are you robbing banks on the side?”

Hard as he tried, he couldn’t tamp the blush creeping up his neck. A former girlfriend who managed an upscale resale shop introduced him to the concept of gently used clothing. Fleeting thoughts of recycling dead men’s wardrobes gave him the willies for a while. So did the chance of acquiring Carleton deHaven’s castoffs, until Jack realized his ex-wife’s hotshot husband was about twice his size.

Across the shoulders and trouser inseams, he allowed. Where it really mattered…well, he had no complaints and damn sure hadn’t received any.

“It’s been a good year and there’s a lot of it left.” If you’re gonna lie, sport, lie big. “Make that a great year. Business slowed down a little last month, but all in all, I thought I was due a few new threads to celebrate.”

“Threads?” Belle chuckled and leaned back as the server settled a plate of Dover sole garnished with squash and broccoli in front of her. Jack had ordered it for her, as well, timing the arrival perfectly.

“You are such a dweeb,” she said. “Fortunately, it’s one of your charms.”

“Thanks.” Jack snorted. “I think.”

After assuring the server that he wasn’t the dweeb to whom she referred and that nothing else was needed, Belle picked up her fork, then frowned at the still empty place between Jack’s elbows. “You’re not eating?”

“Can’t.” He glanced at his watch. “Got to meet Gerry Abramson at his office in about fifteen minutes.”

She forked in a bite of fish. Her expression inferred it was tasty, but nothing special. “You should’ve told me when I invited you to lunch.”

“If you hadn’t been forty-five minutes late, it wouldn’t have mattered.”

“I’m punctual in my own way.” She waved at her drink and plate. “You could have eaten something while you were waiting. Grazed at the salad bar, at least.”

Jack shook his head. “Mama raised me better than that.” He added, “And I scarfed a stack of flapjacks at the diner, before you called.”

Actually, before Gerry Abramson had called. If Belle had called earlier, Jack wouldn’t have gone next door for breakfast. The food at Al’s 24/7 Eats could torture Jack’s gut, even when it didn’t feel like a pretzel that slipped under a couch cushion last New Year’s Eve.

Jack took a drink of ice water and wished it were Chivas. A slug of liquid relaxation would take the edge off his premeeting jitters. He couldn’t care less what type of work the independent insurance agent offered. The domestic Jack expected to collect on Monday night had run sobbing from the restaurant. The heartbroken client stuck him with the dinner check, in lieu of a personal one.

By Wednesday afternoon, the office’s quietude had him clicking on the desk phone’s handset, hoping the line was dead. It wasn’t. In fact, the dial tone had an increasingly mirthful quality, as though Ma Bell were having a few laughs at his expense.

“Jack,” said the gorgeous, similarly named redhead dissecting her entr?e. “Are you okay?”

He hesitated. When someone asks if you’re okay without making eye contact, it’s probable that he or she is anything but. Misery not only loves company, but it also graciously cedes the floor to yours, so his or her own appears empathetic.

Except the woman who’d been his wife for eight years and his best friend for twice that was a straight shooter. It had attracted him at the outset. After Belle dumped him for being an immature moron, her brand of honesty was what he’d missed most in subsequent relationships.

Maybe hanging with the country club set was finally wearing off on her. You can’t fake going with the flow forever. Eventually the current sucks you in, or you say “Screw this bullshit” and wade to shore.

“This year hasn’t been that good, and the suit’s secondhand,” Jack confessed. “This and a couple of Brooks Brothers set me back a friggin’ fortune. Not counting alterations.”

“I guessed as much.”

Frowning, he reached under his arm, thinking he’d pulled a shrewd move like forgetting to clip off the price tag. Nope, and nothing up his sleeves but shirt cuffs, either. “So how’d you know?”

“Guys who can afford designer clothes don’t wear them with Kmart shirts. Or ties. Or twenty-dollar watches.” Instead of smug, Belle looked concerned. She pushed away her plate and fingered the stem of the martini glass. “How bad is business?”

“Flat.” Jack smiled. “And about an hour from an uptick with Abramson’s retainer.”

“For what? A slip-and-fall? Workman’s comp case?”

Both were a P.I.’s bread and butter. Insurers and attorneys hired investigators to expose phony personal-injury claims and employees pocketing compensation pay for job-related accidents. It was astonishing and pretty sad how often paid leaves for, say, a ruptured disc inspired a claimant’s urge to reshingle his house.

Jack said, “Abramson mentioned taking a hit from a string of residential burglaries.” He stifled an impulse to check the time. Belle, of course, wasn’t wearing a watch. “So, how’s life treating you?”

Meaning, Carleton better be treating her well, or Jack would cheerfully break him in half. Too cheerfully, he admitted, but protectiveness fueled it, not jealousy.

“Just between us, I’m a teensy bit bored. Nothing a baby wouldn’t fix, if my ovaries would cooperate.”

Belle signaled the server for the tab, then pointed at her plate, requesting a go box for it. “You have no idea how many times I prayed to my crotch to get with it when my period was a little late. Now I’m hollering up there, ‘Swim, boys. Swim.’”

Jack was supposed to laugh. He said, “I didn’t think you wanted kids.” Pride bit off, With me.

“Woman’s prerogative. One baby would be okay. Wonderful, actually.” Belle drained her glass and blew out a breath. “Carleton isn’t the paternal type, but I’ll be damned if Abdullah Whatthefuckever will be our sole heir.”

“Abdu—oh. The dog.”

“How dare you call a champion afghan hound a dog. The old biddies at Westminster would have your head. So would the harem he’s servicing in Florida.” Belle autographed the credit card chit. “That hairball on stilts is higher maintenance than I am.”

Jack chuckled. “That’s saying somethin’, kid.”

Motion outside the window caught his eye. Vaguely attuned to Belle’s continued slander against man’s best friend, Jack leaned over the table, expanding his view of the restaurant’s parking lot.

The lunch crowd had pretty well winnowed to vacationers as logy as over-the-road truckers who were seventeen hours into a ten-hour day. Jack’s Taurus was baking in the mid-July sun. Belle’s caf?-au-lait Mercedes coupe was parked a half-dozen rows east and farther from the restaurant’s entrance.

Here and there, customers prolonged goodbyes, nodding and talking over the roofs of their vehicles. No familiar faces among them—no white-and-Bondo-colored subcompacts in the vicinity.

Still scanning the lot, Jack said, “You haven’t noticed anybody, um, hanging around outside your house lately, have you? A strange car cruising by, anything like that?”

When Belle didn’t answer, he looked at her. “Hey, no cause for the big eyes. Just curious, that’s all.”

Belle extracted a pair of sunglasses from her bag and slipped them on. Swiveling in her chair, she said, “I knew you were in trouble. What is it this time? Another pissed-off husband swinging single? Somebody pink-slipped after your background check?”

“I’m not in trouble.”

She pulled down the shades an inch and peered over the frames.

“I’m not,” Jack insisted, then groaned. “There’s this mope—twenty-something, big as an upright freezer. He tagged me for a job, I turned him down, gave him some excellent career counseling and sent him on his way.”

Belle’s stare narrowed, but remained as steady as twin-beam halogens. Her fingers waggled, Keep going.

Jack peeled back his suit coat sleeve for a look at his watch. If he didn’t haul asphalt in three minutes, he’d be late for the appointment with Gerry Abramson. “The kid thought he’d impress me with my own r?sum?, financials and an activities report.”

“You mean he tailed you?”

Jack scowled at her apparent amusement. “If I hadn’t been working a domestic, I’d have spotted his crap-mobile—” he snapped his fingers “—like that.”

“Uh-huh.” A fingernail clicked a riff on the tabletop. “You think he’s stalking you.”

“Not really.” Saying it didn’t make it true, but Jack liked the sound of it. “Trust me. He’s about as built for covert surveillance as Sasquatch.”

Belle pondered a moment. “Then you’re afraid he’ll use info from the dossier on you to stalk me.” It wasn’t a question. And there wasn’t a molecule of fear in her tone.

“It occurred to me.” Jack stood and held the back of her chair to steady it. The scenery below provoked a mental wolf whistle. Belle McPhee deHaven had an unquestionably fine set of legs, but it was the peek at her cleavage that brought back many a fond memory.

She and Jack epitomized a couple who should never have parlayed friendship into matrimony. He was damn lucky he’d escaped the latter without destroying the former.

He walked her out, saying, “Okay, I’ll admit, this dude gave me the heebie-jeebies. You know the type. A schlump, except the eye contact’s too long and a touch too intense.”

“Does this schlump have a name?”

“Brett Dean Blankenship.” Taking Belle’s keys, he pressed the fob’s remote button to unlock the Mercedes’s door. “About six-three and four hundred pounds of solid flab. How he packs it into a Chevy Cavalier defies physics.”

Belle scanned the parking lot, as if daring Moby Dick to surface. “Thanks for the warning.”

“At most, it’s a heads-up.” He kissed her lightly on the lips. “Sorry I have to run.”

“I’m used to it.” She flashed a no-insult-intended smile.

Jack couldn’t tell through her sunglasses, but bet it didn’t reach her eyes. Something was bothering her. He could feel it. “How about meeting me for a drink later? If Abramson’s retainer is over a couple of grand, I’ll even buy.”

“I wish I could.” Belle sighed as though she meant it. “Carleton and I are meeting some people for dinner at the club.”

Bars kicked off happy hour at four, but Jack gave her a rain check. “If you, uh, want to shoot the breeze some more, you know the numbers.”

She nodded and pulled the car door shut.

By the time Jack reached the Taurus, he decided his imagination was working double overtime. An occupational hazard for a semi-underemployed snoop. Belle’s admitted boredom wasn’t a crisis, even if the rival for your husband’s affections was a trophy dog. And he hadn’t seen Blankenship as much as sensed him.

He dawdled a moment beside his car to let the blast-furnace heat escape the open door. Belle was right about his being a lousy husband and provider, he thought. But for all the things she’d ripped him for, boredom had never been one of them.

The National Federated Insurers’ office was housed in a remodeled Asian restaurant. The mud-brown exterior and pagoda roof reclad in cedar shakes evoked Jackie Chan Does Sante Fe, but the parking area was large enough for employees, visitors and a bank’s repossessed-vehicles sales lot.

Jack perused a sweet electric-blue speedboat marooned on its trailer. Babe magnet. Babe-in-a-bikini magnet. He could be the Captain and she, his Tennille. The fantasy shimmied and vanished, like a cartoon genie into a bottle. Babes young enough to wear bikinis probably wouldn’t know the Captain and Tennille from Captain Kangaroo.

On that depressing note, Jack entered the insurance agency’s reception area and gave his name to the blonde behind the counter. Without missing a beat of her cell phone conversation, she pointed over her shoulder at Gerry Abramson’s private office.

A double row of desks resided where buffet steam tables had fed the all-you-can-eat multitudes until a health department inspector contracted botulism. Three of the agency’s four workstations were unoccupied. At the back on the window-wall side, Wes Shapiro waved Jack on.

The office manager wouldn’t be picked out of a lineup if a witness had a snapshot of the assailant. Medium build, medium height, medium everything from buzz cut to wingtips. One of those guys who looked the same at his high school graduation as he did at the thirtieth reunion. And not in a good way.

“How’s it going, stranger?” Wes stuck out a hand. “I haven’t seen you since the snow was flying.”

Park City received a total of three inches all last winter, but the slip-and-fall claim Jack investigated turned out to be genuine. When the victim’s civil suit against the negligent store owner went to court, Jack would testify for the plaintiff. Gladly testify. Last he’d heard, she was still in a wheelchair.

Wes lowered his voice. “I told the boss to call you two months ago.” A thumb pinched an index finger. “The cheap son of a gun has the first dollar this agency ever made.”

“Framed and hung on the wall, no less.” McPhee Investigations’ first dollar was encased in Lucite on Jack’s desk. Classy.

“Tell Gerry I’ll have the files together in a few,” Wes said. “He’ll nag me on the intercom anyway, but the photocopier’s a two-speed model. Slow and broken.”

Jack continued on, turning into a corridor with gender-specific restrooms on his right. Wes’s parting remark was an ode to middle management. Nowhere to go but out imposed a constant straddle between indispensible and justifying your existence.

He and Gerry Abramson shook on their mutual gladness to see each other. For as long as Jack had known him, the independent insurance broker had threatened retirement. Today, a hypertensive complexion and bulldog jaw implied a fatal coronary might punch Gerry’s ticket before dinnertime.

Jack asked after Letha, Gerry’s wife of forty-seven years. The vivacious grandmother of nine was battling Parkinson’s disease.

“She has her good days and bad.” Gerry winged his elbows on the arms of a leather desk chair. “The doc’s put her on a new course of treatment. It’s experimental and costs the moon, but it seems to help.”

He shook his head. “Almost a half century in the insurance business, and I’m fighting tooth and toenail with our carrier to cover the meds.” A bitter chuckle, then, “And losing.”

“Then chumps like me don’t have a prayer.” Jack rapped on the visitor chair’s oak frame. A sole proprietor fears extended illness and a debilitating injury more than the IRS. No work, no income. The flu bug can knock a zero off a month’s earnings.

“Time was,” Gerry continued, “and not that long ago, when I felt good telling customers not to worry. Fire? Surgery? Hail damage? We’ve got you covered.”

A crooked finger ratcheted down the knot in his tie, as though it were the source of discomfort. “Nowadays, I’m the villain with a briefcase full of loopholes and exclusions.” He grimaced, levering the collar button backward through its corresponding hole. “And a lot smaller check than they hung their hopes on.”

Jack wondered why Gerry didn’t sell out and retire. What kept him coming to this cozy, thick-carpeted office paneled in genuine walnut and adorned with framed certificates of achievement and appreciation? A national newspaper’s bar chart recently rated the public’s attitude toward various professions. Attorneys historically ranked number one in the most-despised category. The poll’s results now placed insurance agents in the lead by several percentage points.

Gerry Abramson had two first loves. Clinging to a semblance of control over an industry he hardly recognized wasn’t as painful as watching a bastard named Parkinson steal away his wife and being helpless to stop him.

“How about a soda?” he said, rolling backward in his chair. He opened a minifridge built into the credenza. “Bottled water? Chilled cappucino?” He winked. “Just between us, these juice boxes for the grandkids aren’t bad with a shot of vodka stirred in.”

Jack declined and was relieved when Gerry snapped the ring tab on a can of diet cola. The man had every reason in the world to spike an orange drink at two o’clock on a hot July afternoon. The Abramson clan photo atop the credenza symbolized eighteen better reasons not to.

“This job you mentioned on the phone,” he said. “Since you didn’t specify, I’m guessing it’s a fraudulent property-loss claim. Probably a high-profile customer.”

Gerry glared at the doorway, then jabbed an in-house button on the console phone.

“Here’s the copies,” Wes said, entering the office at the precise moment his employer’s call connected. He cut a look at Jack, as though delivering the punch line of a private joke.

After the handoff to Gerry, Wes pulled over a second visitor’s chair. His backside was approaching a landing, but hadn’t quite touched down when Gerry cocked his head at the phone. “Three lines are on hold.”

Wes nodded. “One for Chase and two for Melanie. They just came back in from their claims adjustments.”

“Then take one of Melanie’s until she’s freed up,” Gerry said “And, do me a favor and close the door on your way out.”

“Oh. Sure thing.” The office manager left the room smiling. Behind him, the door shut with a barely audible snick.

Gerry rolled his eyes. “Wes wants to be an investigator so bad it’s almost painful to see.”

Thinking of Blankenship, Jack replied, “Doesn’t everybody?”

The copied files Gerry parceled out concerned a series of residential burglaries dating back to Memorial Day weekend. “Here’s where it gets interesting.” He gave Jack a sheaf of police reports. “The same thief or thieves hit last year, starting Memorial Day, then went to ground Labor Day weekend.”

He paused to let Jack skim the pages. “Luck of the draw, maybe, but only two of last year’s targets were National Federated clients. This year, the so-called Calendar Burglar has already nailed three of my policy holders.”

The nickname rang a bell—the tiny baby-shoe kind, not a tolling brass one. By the number of reports, the reverse should have been true. “Why haven’t I seen anything in the newspaper about this?”

“The Park City Herald focused on it to some extent late last summer. You know, ‘Another west-side home burgled while owners on vacation.’ Or east side. Or south side. Then the usual PD information officer quotes on home security, warnings about disclosing travel plans to strangers, etc.”

Gerry drained the soda can and lobbed it at the trash bin. “Property-theft complaints always jump in the summer and during the holidays. By the time the cops and the newspaper connected these particular dots, the Calendar Burglar vamoosed.”

“Feeling the heat,” Jack speculated. “Moved on to cooler pastures.”

“That was the assumption, except a unit detective followed up in his spare time. Feelers put out to regional PDs netted no thefts that resembled these—the M.O. or an exclusive preference for jewelry.”

Gerry allowed that the burglar could have switched specialties, wintered in a warmer clime or been jailed on an unrelated charge. “Whatever caused the lull, he’s back. The Herald isn’t happy about keeping the story low profile, but some influential victims and real estate developers don’t want their neighborhoods depicted as crime scenes.”

“God forbid.” Jack snorted. “They may as well leave out cookies and milk for this dude. A little snack for bad ol’ anti-Claus.”

“Residential watch groups were alerted in early June. Private security and police patrols in probable target zones have been increased.”

“Uh-huh.” Jack’s finger tapped the prior Sunday’s date on the most recent burglary complaint. “Fairly obvious, what a big friggin’ bite that’s taking out of crime.”

“I want him caught, McPhee.”

Jack looked up. The tone and content of Gerry’s statement weren’t particularly open to interpretation. “You want me to catch a burglar?”

The insurance broker leaned forward and braced his elbows on the desk. “I hope your schedule’s clear enough, or can be cleared to devote full-time to this.”

There were some less than lucrative jobs pending on Jack’s calendar. Otherwise, if the schedule had been any clearer, he’d be applying for a shopping-cart jockey’s job at the local Sav-A-Lot.

National Federated’s retainer would be commensurate with exclusivity, but a scratching sensation behind Jack’s sternum hinted that Gerry Abramson was holding something back.

Perhaps an untranscribed chat with a crime-unit investigator who suspected this Calendar Burglar carried an AK-47 in his pillowcase. Most housebreakers aren’t armed; county jail or prison-time on a theft rap is measured in single-to double-digit months. Add a weapons charge and it’s usually sayonara for a long stretch.

But kill somebody with it—say, the P.I. on your case—and it’s twenty-five to life. A punishment befitting the crime, Jack thought, except for me still being dead.

“The newspaper may be downplaying the story,” he said, “but this victims list must have lit a bonfire under the police chief’s butt.”

Gerry nodded. “It hasn’t slowed, much less stopped these thefts. If the Calendar Burglar isn’t arrested before Labor Day weekend, it stands to reason, he’ll disappear again.”

And bloom like jonquils along a fence row next May. “I understand the reasoning, Gerry. To be honest, just thinking about it has my motor running, and the fee for services could be a beaut.”

Jack laid the paperwork on the desk, then sat back and crossed a leg on his knee. “What I don’t get is why you think I can make a tinker’s damn worth of difference.”

“Fresh eyes. Fresh perspective.” His gesture relayed “If I’m footing the bill, what’s the problem?”

The response was credible, even logical, but a tad too quick. Jack thought back to Wes’s earlier remark about advising Gerry to contact McPhee Investigations shortly after the burglaries recommenced. Then the polite bum’s rush Wes received when he tried to invite himself to the powwow.

“You think Shapiro’s the Calendar Burglar,” Jack said. “He covered himself by concentrating on other insurers’ clients, then either greed or smarts told him he’d better dip into the home well, or somebody’d get wise.”

Gerry’s expression slackened. Skin folds lapping his eyelids retracted, as though an instant blepharoplasty had been performed. Chuckles escalated to a belly laugh. “Wait’ll I tell Letha. Picturing Wes tiptoeing around like Cary Grant in that old cat burglar movie will be stuck in our heads for who knows how long.”

Great. Now that he mentioned it, the image implanted itself in Jack’s mind. Sort of like Don Knotts resurrected for a remake. No, not quite that big a departure. Jerry Stiller, maybe. Or What’s-his-name—that average Joe born to play average Joes.

“It’s as simple as this,” Gerry said. “I’m an independent insurance agent. A hub in a wheel with multiple spokes. When loss claims hike, instead of one provider’s boot on my neck, it’s a centipede.” He blew out a breath. “I shouldn’t have to tell you, I don’t need the stress.”

A half hour later, Jack left the building with an armload of files, a retainer check and no idea how he’d earn it.

4

Single-story duplexes are usually long rectangles with mirror-reverse floorplans. By the county assessor’s definition, two contiguous residential units separated by a foot-thick rock firewall were patio homes. Very la-di-da, in Dina’s opinion, but such was government work. Whether duplex or patio home, the bisected building wasn’t rectangular, either, but an L painted a cruddy shade of gray.

The units shared a three-quarter pie-shaped front yard, a sweetgum tree and views of an adjacent redbrick warehouse, but respective tenants seldom saw each other. The jackknifed design had the neighbors facing north at the corner of Rosedale Court and Lambert Avenue; the Wexlers’ side pointed due east on Lambert at its intersection with Spring Street.

Visitors directed to the corner of Lambert and Rosedale would idle at the curb, look from one unit to the other and mutter “Eeny, meeny, miney.” Occasionally they chose the right “mo.” A few hit the gas and drove away in a huff. Those who rang the Wexlers’ doorbell in error kept them apprised of the current neighbors’ last name.

As Dina cruised up Lambert Avenue at 1:15 a.m., the Rosedale side’s windows were dark. Lights blazed from Casa Wexler as if a party was in progress. Where Harriet’s energy-conservation policy once consisted of “Flip off that switch when you leave a room. You think I own the electric company?”, evidently, she now thought her daughter did.

Dina pulled past the mailbox, shifted the Beetle into Reverse and backed into the driveway. The engine hacked and sputtered. Mechanical bronchitis was typical of vehicles with a couple of hundred thousand miles on their odometers.

Someday she’d have the money to restore it to its original…well, glory was a bit highfalutin for an ancient VW. She’d settle for a new milky-cocoa paint job and straightening the Val Kilmer sneer in the rear bumper.

The Beetle was as short in the chassis as she was, but the single garage wasn’t deep enough to squeeze between the wall and the car to open the front-end trunk. She shifted into Neutral, yanked on the emergency brake, then slumped in the seat. She was just too pooped to muscle up the garage door, back in the Bug, unload her stuff, then jump for the rope tied to the door’s cross brace to pull it down again.

“Someday number two,” she said. “I’ll have a garage with an electric opener and shutter.”

Leaving the Beetle to the elements, she reached into the trunk and wrestled with the magnetic Luigi’s Chicago-Style Pizza sign earlier peeled off the driver’s-side door. Her hobo bag slung over one shoulder counterbalanced the canvas tote on the other. Quietly, she closed the trunk, then relocked it.

The duplex’s front door swung open the moment the key was inserted. Dina groaned in frustration. Sirens and extended commercial breaks often lured her mother from the world that was her chair to survey the larger, outside one. When the TV program resumed, or no disaster was visible beyond the stoop, she’d shut the door and call it good.

Harriet Wexler could not—or would not—get it through her head that the day was long gone when locked doors and drawn curtains meant you had something to hide.

Inside, an infomercial hawked its wares to an unoccupied glider rocker. The habit of leaving on the TV “for company” impelled silent prayers that her mother hadn’t toddled off hours ago to the bathroom and collapsed in a heap on the floor.

Dina left her purse and bag on the table and tiptoed down the hall. Whuffly snores met her midway. In the master bedroom, clear plastic tubing tethered Harriet to the oxygen machine at the end of the bed. Yards of extra hose lassoed the cannonball footpost.

In the light slanting from the open bathroom door, she resembled a child actor made up and bewigged to play her future self. Fingers curled over the bedcovers pulled up to her chin suggested a foil for pixies and their nightly tug-of-war with the blanket.

Dina eyed the machine’s distilled-water level, then blew her mother a kiss. “Sweet dreams, Mom.”

Naturally, Harriet continued to insist she didn’t need oxygen, though her color and energy had improved in the past four days. Dina worried about her tripping over the tubing, but fear of breaking a hip made Harriet extracautious. All in all, the two Bobs’ no-fuss, no-muss solution deserved a Nobel peace prize.

In the hall bathroom, Dina ran water in the sink and pretended the mirror above it didn’t exist. Off with the black cargo pants, her sour-sweaty top and bra; on went the giant Mizzou T-shirt she’d slept in the night before. Soaping and rinsing her face felt wonderful. A hot shower would be ecstasy, but water tattooing the plastic tub surround sounded like marbles in a cocktail shaker.

Her face buried in a hand towel, she yelped when a voice said, “Where the devil have you been, young lady?”

Dina’s head whiplashed toward the door, her pulse spiking a zillion beats a minute. Clutching the towel to her chest, she shrieked, “Jesus Chr-ist, Mom. You scared the livin’ hell out of me.”

By Harriet’s expression, she was gratified to know she hadn’t lost the ability to strike terror in the heart of her kid from ambush. “That pizza joint closes at eleven on weeknights.” She sniffed several times, then puckered her lips. “This is Thursday, you look like you’ve been dragged through a knothole backward and what I smell ain’t pepperoni.”

“Oh, yeah?” Dina flinched. Sure, her defense strategies were years out of practice, but they hadn’t been that lame since fourth grade. What popped out was a snotty, even lamer, “Technically, it’s been Friday for almost two hours.”

“You said you’d be home before midnight.”

“I said I’d probably be home by midnight.” Dina hung the damp towel on the bar behind her, smoothing the wrinkles and leveling the hems. “If you needed me, all you had to do was hit the panic button.”

An emergency alert device hanging like a pendant around Harriet’s neck was programmed to automatically dial Dina’s cell phone. An autodial to 911 would be faster, but a city ordinance prohibited a direct connection to an emergency dispatcher. It was up to Dina to contact emergency services.

“Too many false alarms for a direct call,” a city official told Dina. “An average of sixteen a day when the city council passed the ordinance. And that was twenty years ago.”

A subscription service would relay confirmed panic-button emergencies, but it cost forty dollars a month. Dina couldn’t afford it and a cell phone, too.

“I’m sorry, if I—” The doorway was empty. Peering out, Dina glimpsed the tail of a seersucker housecoat rounding the corner into the dining room. When Dina caught up with her mother, she was fumbling with the tote bag’s zipper.

“What do you think you’re doing?” coincided with the TV announcer’s “Only thirty seconds left. Act now, before it’s too late….”

“Since you won’t tell me what you’re up to,” Harriet said, “I have to find out my own self.”

Paper crackled as she jerked out three white pharmacy sacks, their tops stapled shut. Her righteous scowl deflating, she delved for paydirt at the bottom of the bag.

“What’s this?” she inquired, an “Aha!” implicit in her tone. The alleged contraband emerged, cocooned in a plain plastic bag.

“Okay, you got me,” Dina said. “You’d think I’d learn it’s impossible to put anything over on you for long.” She pulled out a chair and sat down hard. “Go ahead. Open it.”

Hesitating, her eyes downcast and despair evident, Harriet unwrapped whatever Pandora’s box she’d imagined and now wished she’d left alone.

While she stared transfixed at the carton, Dina said, “The pharmacist on the graveyard shift had customers stacked up three deep when I walked in. That’s why I was so late. I wanted to ask some questions, or better, get his recommendation, instead of buying just any ol’ electronic glucose monitor off the shelf.”

Feeling guilty, among other things, for leading on her mother, letting her deliver her own comeuppance, Dina added, “The pharmacist showed me, it really is almost painless. No more finger-sticks to dread three or four times a day.”

Harriet ran a knuckle under one eye, then the other. “I shouldn’t have—”

“Oh, hush. It’s as good a surprise now as it would’ve been in the morning.”

“Yes, and you’re the sweetest daughter in the world for buying it, but—” She picked up the empty bag and started fitting the carton back into it. “These things aren’t cheap. Why, a fancy gizmo like this—”

“Is top-of-the-line and worth every penny.” Dina snatched the receipt from her mother’s hand and crumpled it. The shopping bag was taken away and wadded. “You’d buy one for me, if I was being poked and pinched bloody all the time, so end of discussion.”

Oops. She grinned, hoping to magically turn the last part, that teensy finis which might be interpreted as an order, into a joke. A witty rejoinder. A—

Her mother bent down and kissed her cheek. “Thank you, baby. You shouldn’t have spent the money, but it is a trial when my fingers are too sore to work a crochet hook.”

She was quick to grouse about everything from foods she craved that were on the restricted list to unwed celebrities who hatched their young like guppies. Aches, pains and physical discomforts were endured in silence.

Bravery was admirable. Except it forced constant vigilance, attentiveness to every subtle twitch, grimace, blemish—any deviation from whatever constituted normal. Had Harriet hovered over Dina and Randy as diligently when they were children, they’d have whistled up the stork and demanded a change of address.

The paper bags contained an anti-inflammatory prescribed for arthritis and two types of ophthalmic drops to control Harriet’s glaucoma. One of the latter required refrigeration. As she moved to the kitchen, Dina cocked an eyebrow, angled sideways in the chair, then looked back toward the hall. No oxygen hose trailed along the carpet.

“Something seems to be missing. But jeepers, I can’t imagine what it is.”

Her mother shrugged and closed the fridge. “So I left my leash on the bed for a minute or two. What’s the harm?”

Dina dropped her head into her hands. Maybe it wasn’t too late to whistle up that stork.

Jack raised his head from his hands and blew out a breath. It stank of beer, rancid onions from the chili dog and rings he’d gulped for dinner and the five pots of coffee he’d chased them with.

A scrambled egg, dry toast and a glass of milk next door at Al’s diner would absorb the acid gnawing craters in Jack’s stomach. A glance at his watch, then at the parking lot visible out the office window nixed the idea. Neighborhood bars had poured their customers out on the street over an hour ago, but Thursday-night-into-Friday-morning crowds were different from weekenders.

Rebels without a brain, in Jack’s opinion. As if knocking back a sixer the night before the work week ended was a form of social commentary. Clock in Friday with a killer hangover and perfect impression of a toilet bowl’s rim carved on your face and that’ll by God show the boss who’s boss.

“Nice attitude, McPhee,” he muttered. “Speaking from experience, I presume?”

He was. His throbbing neck and shoulders brought back memories of regular worship services at the porcelain altar. Hunkering over a desk for hours on end exacted similar punishment with none of the fun of getting there.

Sitting back in his chair, he surveyed the ream of photocopies and newspaper stories separated into categorized stacks. A case beginning with little or nothing to go on was common. One with an old-growth forest in paper form splayed across his desk should solve itself. And might, if he could see the pattern for all the damn trees.

It was there. He was just too bleary-eyed to find it. The usual remedy for mental fatigue was a good night’s sleep. A fabulous idea, if he could unplug his overloaded brain and stuff it in his sock drawer. Otherwise, the yammering in his head would be like the New York Stock Exchange after the opening bell.