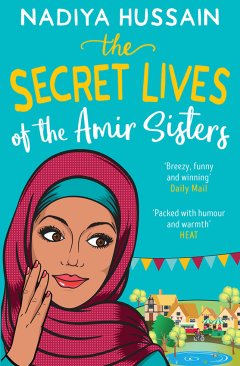

The Secret Lives of the Amir Sisters: the ultimate heart-warming read for 2018

Àâòîð:Nadiya Hussain

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:726.48 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 318

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 726.48 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

The Secret Lives of the Amir Sisters: the ultimate heart-warming read for 2018

Nadiya Hussain

‘Packed with humour and warmth’ - HeatThe four Amir sisters – Fatima, Farah, Bubblee and Mae – are the only young Muslims in the quaint English village of Wyvernage.On the outside, despite not quite fitting in with their neighbours, the Amirs are happy. But on the inside, each sister is secretly struggling.Fatima is trying to find out who she really is – and after fifteen attempts, finally pass her driving test. Farah is happy being a wife but longs to be a mother. Bubblee is determined to be an artist in London, away from family tradition, and Mae is coping with burgeoning Youtube stardom.Yet when family tragedy strikes, it brings the Amir sisters closer together and forces them to learn more about life, love, faith and each other than they ever thought possible.

NADIYA HUSSAIN is the phenomenally popular winner of 2015’s Great British Bake Off, with an ever growing public profile and a future women’s fiction star. Nadiya’s brand is growing beyond GBBO, including a cookbook with Michael Joseph, a children’s book with Hodder, and a TV series: The Chronicles of Nadiya. Her Michael Joseph cookbook, Nadiya’s Kitchen, reached the Amazon bestseller chart, and Nadiya has a strong social media presence, with almost 100K devoted Twitter followers.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2017

Copyright © Nadiya Hussain 2017

Nadiya Hussain asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008192273

Version: 2018-04-17

I would like to dedicate this book to my Baba. For putting up with my teenage angst and telling me ‘One day you will actually like me young lady’. As much as it pains me to admit it, you were right, and I do actually quite like you now.

Contents

Cover (#ub024d1ba-82c8-5a26-8795-6cb459149c29)

About the Author (#u2c98f4a7-e817-5781-a003-08ab2c4f4367)

Title Page (#u3412d1d2-25c3-5ff3-9376-0a89c11d4f5a)

Copyright (#ulink_75a50fe9-0730-5d5c-81bd-9904435506dd)

Dedication (#ued062d63-4861-56b9-b111-e0708a05a301)

CHAPTER ONE: Fatima (#ulink_a598bd8c-b204-520d-8a90-b78ad7e7e45d)

CHAPTER TWO: Mae (#ulink_50a91557-7a9b-5c95-953a-e0b0151617d1)

CHAPTER THREE: Bubblee (#ulink_eb71af69-47fa-58bb-9bac-67b4bfb7f3ac)

CHAPTER FOUR: Farah (#ulink_81ac577d-1b5f-59da-ab7a-a4a33142ac52)

CHAPTER FIVE: Mae (#ulink_af90e17d-18ea-5d19-91bf-148955e605f2)

CHAPTER SIX: Fatima (#ulink_6955e0f7-8e56-52f1-a5dc-d5d80ebec99b)

CHAPTER SEVEN: Bubblee (#ulink_900e9f61-bda4-58fe-bd70-319bef5ecd4a)

CHAPTER EIGHT: Fatima (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE: Mae (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN: Farah (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Fatima (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE: Farah (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Mae (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Fatima (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Bubblee (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Farah (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Fatima (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Mae (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_d4060eb1-32d3-5185-992d-cdafd1ec7ddf)

Fatima (#ulink_d4060eb1-32d3-5185-992d-cdafd1ec7ddf)

It’s going to be fine. I wiped the palms of my hands on my trousers that crinkled from the sweat. Before I realised it my hand lunged towards my bedside drawer, shuffling around to try and find my stash. How could I have run out? Going downstairs wasn’t an option given that I heard Mum on the phone with Jay. That’s the first time he’s called in two months. Every time after a conversation with him there’s always this odd kind of quiet that’s filled with trivial stuff like, Did you get the toilet paper? And Let’s re-arrange the family album. Mum can never quite look any of us in the eye, while Dad goes into the garden to inspect the flowers. I took a deep breath and went to open the window in my room. Just as I’d predicted, there he was, standing with his hands on his hips, staring at his begonias.

I glanced at the next-door neighbours and quickly looked away. Marnie was out, sunbathing, stark naked. My eyes hovered towards her again. Amazing, isn’t it? She hasn’t a care in the world about who’s looking at her and what others might think. What about all the insects in the grass? What if they decided to make a detour right up her … ugh. Still, that is what you call being sure of yourself. Her whole family’s like that. Naked, but sure of themselves. Dad scratched his head and bowed it so low it looked like he might’ve dropped off to sleep. I wanted to go down and talk to him about his flowerbed, but I hate leaving my room – the comfort of its four walls and dim light. I turned around and reached into my drawer again, just to double-check its contents, and right there at the bottom I felt the steely tube; crumpled, but there was hope. Lifting it out, I saw that my tube of Primula cheese had been squeezed to within an inch of its life. I unscrewed the lid and pushed into the top – a meagre bit of cheese poked out of the nose and back in again. Just then I heard Mum rapping at the kitchen window.

‘Jay’s Abba. Come inside,’ she said to Dad.

I watched Dad peer in at her, confused. Not because she referred to him as Jay’s dad – we’re Bangladeshi, after all, and there are some traditions you can’t let go of; like calling your partner by your eldest child’s name. Except in this case – even though I’m the eldest – it’s Jay’s name because he’s their only son. It doesn’t bother me though – not really.

‘Come inside,’ Mum repeated to Dad.

I guess she saw that Marnie was out too. There was nothing for it; I had to go down eventually, anyway, considering what day it was. So, I made my way down the stairs and into the kitchen.

‘Don’t be nervous,’ said Mum as I sat down at the table.

‘I’m not,’ I said, trying to smile without wanting to be sick everywhere.

She blew over me after having muttered a prayer.

‘Have you said your prayers?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ I lied.

She patted my head and put a plate of biscuits in front of me, before going to make tea for Dad. He looked towards Mum, standing at the kitchen hob, and then over his shoulder. Reaching into his pocket, he handed me some money, putting his finger to his lips. I forgot about my nerves for a minute as I mouthed ‘Thank you’ and tucked the money into my jeans pocket. I don’t know why he hides the fact that he gives me money for all my driving lessons from Mum – but it’s become our little secret.

‘Remember,’ he said, clearing his throat. ‘You look into the rear-view mirror every few seconds, they will pass you.’

‘That’s what you said last time, Abba,’ said Mae, who’d wandered in, holding her phone’s camera towards us. ‘It’s time for some new advice. For my video, thanks.’

‘Switch that off and help me make the dinner,’ said Mum to her. ‘Farah is coming later.’

Mae rolled her eyes. ‘Or maybe you should get a new driving instructor,’ she said. ‘Because he’s obvs not doing something right.’

Dad scratched his jet-black hair. I wish he’d let it go grey like normal dads do. No-one actually believes his hair is that black.

‘No,’ he said. ‘You know how long it took to find a Bengali instructor? Lucky he is just in the next town.’

But Mae had already stopped listening and was tapping something on her phone.

‘Don’t worry, Abba – I’ll remember to check all the mirrors,’ I replied before turning to Mum. ‘Is Farah coming alone?’

‘Yes, she’s not staying long,’ said Mum.

Of course she wasn’t. She’d be going home to her husband. I imagined her greeting him as he walked through the door. Or maybe she’d be in the bathroom and he’d call out to her? I do like it when the two of them come over sometimes, though. It’s like watching TV but in real life. Only, every time they leave I’m left with this hollow feeling inside, because it is real life – just someone else’s. I picked up a biscuit to go with the squeezy cheese Mum had just put on the table for me, but it was snatched from my hands. Mae, of course. She handed me a carrot stick instead while eyeing a bottle of olive oil.

‘Mum, that isn’t organic,’ she said.

‘Mae,’ said Dad. ‘We didn’t have organic in our day and we are fine and healthy.’

‘Yeah, right,’ she retorted.

A car horn beeped outside. I gulped as my mum and dad both looked at me. Everyone takes their driving test, I tried to reason with myself. What is there to be nervous about? So what if, at the age of thirty, I’ve failed before? And the time before that? And so many times before that? My heart felt too big for my chest. I took the tube of cheese as I got up and made my way to the front door.

‘Say bismillah before you begin,’ Mum shouted out.

Bismillah. In the name of God. What was the point in telling Mum that I’d tried that before each driving test and it’s not exactly worked so far.

‘I will,’ I called out.

I steeled myself as I put my hand on the front door handle. You can do this. Because whatever happens you don’t just give up on a thing, do you? Opening the door, I saw my instructor’s red Nissan Micra parked outside our home. Ashraf lowered his head, dark hair flopping over his eyes, and waved at me. I took another deep breath before setting foot outside the door.

*

‘You shouldn’t get so nervous,’ he said as I steered the car into a parking spot outside the test centre after I’d had my lesson.

I tried to swallow the lump in my throat as I looked up at the brown building. I can’t fail again.

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘Don’t just say okay. Mean it,’ he replied, softening his tone. ‘You drove well.’

‘Okay.’

‘Fatima, the problem isn’t whether you can do this or not – the problem is you believing you can do it.’

I stared at the steering wheel because he was right, of course. But it was all such an embarrassment. Which thirty-year-old woman struggles this much with a driving test? It’s just that I know if I can do this, I’ll be able to get my life in order. I’d be free. Independent – not have to rely on someone to drop me off or pick me up for my next hand-modelling shoot. I looked at my hands – my source of income.

‘And don’t feel sorry for yourself,’ he added.

I looked at him. ‘I’m not feeling sorry for myself.’

‘Okay, okay,’ he replied, putting his hands up, the cuff of his electric-blue shirt riding up. ‘Just checking.’

I took a deep breath and got a whiff of Ash’s aftershave. Maybe I was feeling sorry for myself.

‘How’s Sam?’ I asked, glancing at the clock and wanting to forget that my test was in under fifteen minutes.

‘Teenage girls will be teenage girls,’ he replied. ‘But she’s a good girl, really. Just hiding it well. Really well. Either that or she’ll take after her mum,’ he added.

I tried to give him a reassuring smile. ‘No. She’s half you too,’ I replied.

‘I’m not sure that counts for much. But at least my son’s tamer. He might be two years her junior but he’s also about ten years wiser.’

‘He does sound it,’ I replied, remembering all the stories I’d heard about him.

It’s so weird to think that Ashraf has two teenage children when he’s not more than five, maybe six or seven, years older than me. It’d be rude to ask.

‘She probably regrets things,’ I said.

He smiled and brushed something off his black jeans. Mae would have something to say about a man who wears black jeans. ‘So uncool.’ I wish I had been as sure of myself at that age; to be able to say what you think out loud. I wish I was that sure of myself now. My little Mae, who’s able to say what she wants and still manage not to offend anyone.

‘If my ex-wife regrets leaving, then her getting married to another man is a huge mistake,’ he said.

‘Oh. I didn’t know. Sorry.’

‘Don’t be. He’s giving her a detached house and an expensive car – all the things I couldn’t. Or didn’t. Either way, it doesn’t matter.’

How did we even get talking about his wife? If you have a driving instructor for long enough you’ll probably end up knowing more about their life than you do your own brother or sister’s. At least, that’s how I feel. I remember when I started my lessons he’d only just left her. She did sound like a bit of a shrew; not that Ash would say as much, but why would you come all the way from Bangladesh to England to marry a man, only to get permanent stay here, then make his life so miserable that he’s forced to leave you?

‘What matters is your test,’ he added. ‘Did your mum tell you to say your prayers?’

I nodded.

‘And your dad told you to check your mirrors?’

‘Yes.’

‘And Mae …?’

‘Gave me carrots.’

‘Good – so everything as usual then.’

I laughed. He must think my family is crazy. They do sound it when I talk about them. Funny that I always feel fonder of them when I tell him about the latest drama in the Amir household. My hands had stopped sweating and when he said it was time to go I didn’t want to reach into my bag for some Primula cheese.

Because we should always remember: what doesn’t kill us, only makes us stronger.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_ad7ef541-486f-5010-91f6-9785346d0c82)

Mae (#ulink_ad7ef541-486f-5010-91f6-9785346d0c82)

‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. That’s my sister, Fatti’s, motto every time she fails her driving test, which would be – not even exaggerating – for the fifteenth time now. That’s right. Fifteen. It’s kind of a rich thing to say when she walked into the house, with cheese all over her chin. Remember, guys: saturated fat does not make you stronger. Just looking at the gooey substance smeared on her face made me want to take a shot of wheatgrass. Anyway, ciao for now. More on the trials and tribulations of a millennial living in a Wyvernage later.’

I came out of Snapchat and stopped jogging on the spot for my warm-down after my run. Checking my Fitbit as I walked into the house, I called up to Dad from the passage.

‘Bet that run would’ve taken care of your headache, Dad.’

Headache – yeah, right. I walked back into the kitchen because where else would Fatti be? ‘Look what I made,’ I said, carefully placing the phone upright so the video captured me opening the fridge.

Fatti looked at the celery salad in disgust, scrunching up the pudgy nose she hates so much, even though I think it’s cute in its own way. But, hey, I’m the youngest in the family – what do I know?

‘Is that camera on again?’ asked Fatti. ‘Where’d Mum put the prawns?’

Of course the camera was on again. What would it take for my family to realise that this wasn’t some hobby now – it was work. I’d have the best GCSE media project in the year. No other student had eleven thousand subscribers on their YouTube channel. I stepped in front of our huge silver fridge. ‘It’s a scientific fact that celery can speed up your metabolism,’ I said, putting the bowl down in front of her.

‘Don’t worry, Fatti,’ said the mothership who’d walked in. She adjusted the drape of her sari and glared at me, which meant I should move out of the way or I might have a slipper thrown at my face. ‘You will pass the test next time.’

And she handed her the prawns, which I guess brought a bit of balance to the synthetic cheese in a tube.

‘Mae, can’t you eat like a normal girl?’ said Mum, looking at my salad. ‘Don’t you want your amma’s delicious curries?’

No, thanks. I’d rather not have a heart attack, but of course I didn’t say that because it would’ve been rude. I stepped back and zoomed the camera in on Mum who put her hand on Fatti’s cheek. I had to shirk off this weird feeling I got – as if I’m missing out on something. I tried to remember the last time Mum put her hand on my cheek. I couldn’t. Just then the front door opened and slammed shut again. Farah tumbled in with about seven shopping bags as Fatti went to help her. There was a look on Farah’s face, which I wanted to capture, but I couldn’t zoom in close enough – what was it? Like sadness, but it disappeared too quickly, because as soon as Mum came into view Farah put on a smile.

‘I see Mae’s busy with her high-school assignment,’ said Farah, raising an eyebrow. ‘Perhaps put the camera down for a moment and help with the bags?’

I rolled my eyes. The thing is, I don’t mean to, but it kind of just happens. Apparently it’s called having an attitude problem. Whatever.

‘Is …’ Farah cleared her throat. ‘Is Bubblee here?’

Farah’s movements slowed down as Mum told her: ‘She’s so busy in London. She said she can’t make it this weekend either.’ Mum’s sigh was audible.

‘All she’d do is smear mud all over the carpet and call it art. Ugh,’ I said, repulsed at the chocolate digestives that Farah put on the breakfast table. ‘Do you know obesity is one of the top killers in the UK?’

‘Tst,’ said Mum to me as she continued: ‘If Bubblee comes I might be able to show her some boys. She is so beautiful – maybe someone will marry her before she opens her mouth. And then at least she will give me grandchildren.’

Mum glanced at Farah not so discreetly, waiting to catch her eye, just so she could give her an aggrieved look. Because that’s how Mum rolls.

‘You haven’t heard that for five minutes, have you?’ I said to Farah.

She pursed her lips as she turned to Fatti. ‘Well. How’d the test go?’ she said, a hopeful look on her face.

Fatti shook her head. ‘But it’s okay. What doesn’t kill you—’

‘—Yeah, yeah,’ I said, catching Fatti staring at Farah’s wedding ring. ‘We know.’

Mum slapped me across the back of the head. I swear I have a bald patch because of her. I got my phone and tapped on the Twitter icon:

Some people have alopecia, others suffer from male-pattern baldness – I have a mother who likes to hit me across the head #Abrasiveparents #Hairloss #Aintfair #Meh #Whatever

Fatti walked out of the kitchen as I saw Farah’s eyes settle on our sister’s widening arse. I mean, hello, why doesn’t anyone say anything to her? I’m the only one who cares enough about her arteries to make a celery salad, and then I’m the one everyone shouts at for being ‘insensitive’. Yeah, well, when she’s in hospital because she needs a bypass at the age of thirty-five, then we’ll talk about who’s been insensitive.

‘Mum, you really need to stop buying all that cheese in a tube,’ said Farah.

Mum, as usual, opted for selective hearing and asked Farah whether she got more prawns. Fatti likes to mash them up and mix it with the cheese. If that doesn’t make you vom, I don’t know what will.

‘Here,’ said Farah, handing an envelope to Mum. ‘Five hundred.’

Mum quietly took it and slid it into her drawer. More money. From Jay, the prodigal son. Why our brother doesn’t give it to Mum and Dad directly, I don’t know. I decided that no-one cares about what I have to say and took the bowl of salad upstairs to Dad.

‘Come in,’ he said as I entered Mum and Dad’s room.

He was lying on the bottom bunk, scratching at the wood panel above him, but sat up, craning his head forward so he didn’t hit it against the bunk’s panel.

‘How’s the headache?’ I asked.

‘Hmm? Oh, yes,’ he replied, putting his hand on his head. ‘Better.’

Of course it was.

‘Mum was on top last night then?’ I said, settling down next to him, holding on to the bowl of salad.

He looked at me, momentarily taken aback. ‘Oh. Yes. On top,’ he replied. His eyes settled on the salad.

‘I guess you don’t want it either,’ I asked.

They say youth is energy. Like, you should be grateful for it and stuff. But youth to me feels like wading through a mass of crap, wishing someone would give you direction because you can’t see (because there’s crap in your eyes, obvs). Dad’s top lip twitched – his eyes still on the salad.

‘Yes, yes. I’ll have it,’ he said, picking up a celery stick and crunching into it. It took him about five minutes to swallow the thing.

We sat in silence for a few minutes. Then Dad said: ‘How is school?’

‘Yeah, cool,’ I replied.

He scratched his chin. ‘And, er … this video,’ he said, looking at my phone with concentration. ‘You are filming things?’

‘Correcto-mundo.’

He looked at me, confused.

‘It just means, yes, Abba.’

‘Ah, good, good,’ he replied.

‘My teacher said I’ve got talent,’ I told him.

‘That’s very good.’

I waited for him to ask me some more questions: like, what kind of talent, and what will you do with it when you leave high school? That kind of thing.

After a bit more silence, he asked: ‘You like those smoothies, don’t you?’

‘Only the homemade ones, because you can’t trust what supermarkets put in stuff.’

‘But we buy everything from supermarkets.’

‘Yeah, but they’ve got all those e-numbers and stuff.’

‘E-numbers?’

I nodded. ‘It’s unhealthy. It’s killing us.’

‘But there is nothing wrong with us,’ he replied, looking at his body up and down as if it was an example of supreme health.

It was like trying to explain fashion to Fatti. I gave up.

‘You know what is healthy?’ he asked.

‘What?’

‘YouTube,’ he answered. ‘Very good. For the brain.’

What the hell was my dad going on about?

‘Er, okay.’

He hesitated then said: ‘You said you had scribers.’

‘Subscribers, Abba.’

‘Oh, yes. That’s what I meant.’

‘And?’

He cleared his throat. ‘Just … carry on.’

‘Sure, Abba. Thanks.’

We both sat in silence for a few minutes.

‘Oh, I know,’ I exclaimed. ‘I’ll make tofu curry tonight. For dinner.’

Dad nodded, as if there was someone forcing the movements of his head, and patted me on my back. It’s not on the cheek. Not like it is for Fatti, or a hand on the head like it is for Farah; the pinching of the nose like it is for Bubblee. But who really cares?

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_f59f320b-93af-53ee-bffb-530befab3260)

Bubblee (#ulink_f59f320b-93af-53ee-bffb-530befab3260)

‘You need to get the contours right,’ said Sasha, clearing her throat and observing my latest piece. ‘It’s … it’s coming along.’

I looked at my sculpture, Sasha’s hand resting on the hip of my centaurian woman. The idea is to subvert expectation by showing the interchangeability of sexuality.

‘But that’s the point,’ I replied. ‘What is right?’

‘Still,’ she said, walking towards the window of my poky studio flat and lighting up a cigarette. She regarded the sculpture again. ‘I’m not sure your aim is quite, you know, coming across.’

Sasha really has nothing good to say about anything. My mobile rang and ‘Mum’ flashed on the screen.

‘You gonna get that?’ asked Sasha.

‘Later,’ I replied, looking at the sculpture.

Something was amiss, but why should that be wrong? Isn’t it like in life, where the imperfections are hard to pinpoint and yet are just there?

‘You’ve go to stop over-thinking things,’ she said. ‘Your problem is you always want to create something with multiple layers of meaning, but that should be the end result, not the starting point. Art is about feeling.’

‘A glimpse of the world as you see it,’ I muttered, reminding myself.

Well, I definitely see it as being amiss, so I must’ve been on the right track. My phone rang again. This time Dad’s name flashed on the screen.

‘How many times do they call you in a day?’ said Sasha. ‘No point in exhaling. They can’t hear you. Just pick it up.’

‘I’m busy.’

Before I knew it, Mae was FaceTiming me.

‘Is someone dying?’ I said, picking the phone up, staring down at Mae’s pixie-like face. ‘I’ll call you back.’

‘She failed again,’ she said.

‘Who failed?’ I asked.

‘Fatti.’

‘What?’

‘Tst, her driving test, of course. Don’t you remember?’

‘Oh, yeah. I forgot. I hope you hid the cheese from her,’ I said.

I glanced over at Sasha who was still leaning out of the window, puffing away.

‘One sec,’ I said to Mae, muting the phone and putting it face-down on the sofa while I asked Sasha to put her cigarette out.

‘It’s not like your family can see me,’ she responded.

‘What if they do? Then they’ll think I smoke and it’ll be something else for them to rail against. It’s bad enough I’ve left my family home and that I’m living alone in London; thinking that I smoke will give someone a heart attack,’ I whispered, even though I’d muted Mae.

Sasha sighed and shook her head, throwing the cigarette butt out of the window.

‘You wouldn’t know you’re a twenty-eight-year-old woman,’ she said as I got back to Mae’s call.

‘What was that?’ Mae asked.

I saw her scan something behind me and it was Sasha, waving at her. Mae waved back unsurely.

‘I’ll see you tonight, Bubs,’ said Sasha before leaving the flat.

‘Don’t you, like, have any other friends?’ asked Mae.

‘What do you want, Mae?’

Mae seemed to be sitting on the steps on the staircase. I recognised the green carpeting against the cream walls. I could just imagine her peeking over the railing, spying on everyone with them unaware of exactly what she’s catching on camera. On the one hand it’s an ethically dubious thing to do, but on the other, I’m glad she has some kind of passion that isn’t related to a bureaucratic, unimaginative career-choice. Thank God there must be some kind of an artistic gene in our family. She made her way down the steps and everyone’s face flashed in front of me.

‘Look who’s here,’ she said, as Mum squinted and recognised me.

‘I tried calling you – where were you? Why didn’t you pick up? I was worried.’

Before I had a chance to answer, Farah’s face was in front of me.

‘Say hello to your fave,’ said Mae.

Farah straightened up from stuffing the kitchen cupboards with God knows what.

‘Salamalaikum,’ she said.

‘Hi,’ I managed to mumble.

The sun shone from the kitchen window, right into her eyes. She shielded them as she asked: ‘How’s the big smoke?’

I shrugged. ‘Better than home,’ I said, lowering my voice.

She gave a faint smile. We might be identical twins, but our smiles are different – hers is soft and sweet. Mine? Well, not so much. She looked away but I couldn’t see what she was doing with her hands. I always did hate it when Farah looked like that; so helpless and at a loss.

‘How’s your husband?’ I asked. Only it didn’t come out in the well-meaning way I intended.

Before I knew it Farah was out of screen-shot, and swiftly replaced with Mae’s face.

‘Where’s Fatti?’ I asked Mae, pretending it was normal to have Farah walk away like that. Actually, it had become quite standard.

‘Well done,’ Mae said, ignoring my question. ‘Farah’s only gone and left now, and I needed to ask her about my tofu curry recipe. You need to let it go, it’s been five years. I mean, come on – so what Farah’s married?’ she added, looking at the leftover shopping. ‘Now I’m going to have to put it all away.’

I wanted to tell her she’s lucky she has Farah who manages to do that for her, as well as everything else.

‘So, she was helping out at home as usual. Not much change then,’ I said.

‘And handing over money from our dear brother, as per,’ added Mae. ‘Who, by the way, decided to call Mum and Dad today. Ugh.’ Mae leaned into the screen as I realised that she’d caught sight of my sculpture. ‘What’s that?’

‘A work in progress,’ I replied, turning the phone the other way.

‘What? Like you?’ She found this a lot funnier than I did and laughed as she made her way up the stairs again.

‘Wait. I wanted to speak to her,’ I heard Mum call out after Mae as she passed the living room.

Not that Mae listened. ‘I’ll pretend I didn’t hear. You can thank me later. Ssh.’

I saw she’d stopped outside Fatti’s room and leaned into the door. Mae put her finger to her mouth, waited for a few moments before shrugging and going into her own room.

‘How’s school?’ I asked, turning around to look at my sculpture, wondering what it was that made it seem so incomplete. What did Mae know? My sisters were so uncultured when it came to anything to do with the art world.

‘Better than your relationship with Farah,’ she replied.

‘Not now, Mae.’

Would I ever be able to say anything to Farah without her taking offence?

Mae shrugged. ‘Whatevs. I’ve got more interesting things to do than think about everyone’s crises anyway.’

Just then there was a loud knock on her door.

‘It’s Abbauuu,’ she said, smiling at our dad. ‘What’s up, Abs?’

‘Your amma needs to talk to Bubblee.’

‘Our amma always needs to talk to someone,’ she replied.

If I’d said half the things at her age that she did I’d have been locked in the cupboard under the stairs.

‘Soz, sis. I did my best but we are all veterans of our familial battles.’

‘Just pass the phone, Mae.’

Before I knew it there was Dad’s face as he spoke. ‘Fatti failed her driving test again so your amma is a little more stressed than usual. Just speak to her for five minutes and make her feel easy.’

‘She’s not going to feel easy until I move back home. And let me tell you, Abba, that’s not happening.’

‘I know, I know.’ He paused as I saw him stop at the top of the stairs. ‘Erm, what is that?’

I’d turned around again without realising that Dad could see the sculpture.

‘Something I’m working on,’ I replied.

‘Hmm.’ He furrowed his eyebrows. ‘And this is what you’re doing in London? Making sculptures of women …’ he leaned in closer. ‘Animals? What is it?’

‘Never mind, Abba. Just give the phone to Amma so I can get the conversation over with.’

I don’t mean for my words to sound short or irritable but that’s just how they come out.

‘I’ll speak to you properly later, okay, Abba?’

He was still looking at the sculpture, worry lines spreading over his features.

‘Hmm? Okay, Babba.’

By the time he’d walked downstairs I heard Mum complaining about Naked Marnie who was apparently out again, basking in the glory of unexpected sunshine.

‘It is a free country,’ I heard Dad say to her.

‘What do you want then?’ said Mum, taking the phone from him and giving me a view of the kitchen walls again. ‘For us all to go out naked?’

‘No-one wants you to go out naked,’ he replied.

‘Hello?’ I said. I had a sculpture to work on, after all.

‘Yes,’ said Mum, putting the phone up to her sour-looking face. ‘I called you two, three times and you didn’t answer.’

‘I was going to call back.’

‘When? Next week? Next month? Next year?’

I didn’t see why, between Fatti failing and Jay calling, I had to be the one who faced her aggression. This is why I make a point of calling home as little as possible. What’s the point when you’re only going to get told off? I’m an adult, for God’s sake. I bet Jay doesn’t get this antagonism. No, the golden child is probably showered with all manners of kindness.

‘Poor Fatti failed again,’ said Mum without any prompt from me.

‘Hmm.’

‘You know how hard it is for her. She doesn’t have your confidence – you should help her but you don’t even answer your family’s calls.’

‘It’s not as if I’m loafing around, Amma. I’m working.’

She looked up at my dad, presumably, and decided to mirror his worried face.

‘But, Bubblee, what kind of work? Look how beautiful you are – such a small nose and light-brown eyes. You shouldn’t take these things for granted. Maybe you should think of getting a proper job where you are making some money. Maybe banking, hmm? Whenever I have a nice boy’s amma on the phone who asks me what you do, I tell her and I never hear from them again. If you had a normal job they would see you and then your beauty would do the rest.’

‘These aren’t exactly the type of people I want to know anyway, and you need to stop trying to find me a husband. I don’t want to get married yet.’

‘Your youth won’t last for ever. Already you’re so old for marriage.’

‘I’m twenty-eight, Amma. And Fatti’s older than me. Why don’t you bug her about marriage? I’m pretty sure she cares a lot more about it than I do.’

Mum shook her head and looked up at the ceiling. ‘Allah, what have I done to deserve a girl who answers back so much? A girl who doesn’t even speak to her own twin sister?’

Which was, of course, a complete exaggeration. I speak to Farah. When we’re in the same room. Which, granted, might not be very often, because I avoid it as much as humanly possible, but that’s for her sake as well as mine.

‘And why?’ Mum continued. ‘Because she married a man?’

‘A man who’s not her equal,’ I replied, feeling the heat rise in my cheeks.

Why does everyone find it so hard to understand? Why couldn’t they see that my twin sister deserved better than this prosaic, uninspired individual? Why does a husband have to be horrible, or abrasive, or neglectful to not be right for you? Of all the things Farah could’ve done with her life, achieved or aspired to, she decided to settle down and marry the first man that asked her. Forget the first man – her first cousin. And I bet it was all because he wanted to stay in England; coming here to study and then conveniently ‘falling in love’ with my sister, who then – na?ve woman that she was – decided to fall in love right back. I mean, don’t even get me started on the notion of falling in love, let alone marrying your mum’s sister’s son.

Mum sighed and muttered something under her breath. ‘And when will you visit your family? Or do we have to wait for someone to die?’

‘Jay’s Amma,’ said Dad. ‘Don’t say things like this.’

I looked as Dad seemed to be putting grass in the blender. ‘What are you doing?’ I asked.

He turned around as he put the lid on the blender after adding a banana to the mix. ‘Making Mae a smoothie,’ he explained.

‘With what?’

‘She likes fresh things, you know. Says that supermarkets are no good, so I took some leaves from the hedges for an extra … boost.’

‘I only say what is true, Jay’s Abba,’ replied Mum, ignoring what was happening in her kitchen.

I mean, how can I take seriously the words of two people who refer to each other as the parent of their only son? Their only son who comes and goes as he pleases, hardly ever showing his face and exists more as an idea than an actual being. Not that he gets any flack for it because, of course, he’s a boy and the same standards don’t apply.

‘Maybe at Jay’s wedding,’ I said, straight-faced.

‘Bubblee,’ said Dad, abandoning the blender and taking the phone from Mum as he glanced at her. ‘Remember she is your mother.’ He looked from side to side as if he wasn’t quite sure of this fact. Or perhaps he was just looking out for a slipper that might come flying his way if he did anything but agree with her.

‘Yes, Abba. Thanks.’

He gave a short nod and winked at me before he ‘accidentally’ hung up on me. Dad will probably end up paying for that in rationed dessert servings tonight.

I exhaled as I sat on the edge of my chair and looked at my sculpture. It was difficult to concentrate, what with Mum mentioning Farah. I turned to look at a photograph of us on my wall; it was taken on our thirteenth birthday. We were so excited about being teenagers. We thought there’d be this shift where things would change and life would somehow be more exciting. And it was in some ways; I discovered art and how a painting could make you feel things that life somehow couldn’t; how there was beauty in the stroke of a brush or the curve of a shape; the way a drawing might speak a truth that reality only hinted at because it never stayed long enough for you to capture it. But art – it kept that feeling static in time, and you could re-visit it and be moved by it all over again, in a different way. I wanted to make people feel that way with my art. And I wasn’t about to give up until I succeeded. Farah never took to art. Or literature. I waited for her to talk passionately about something. I urged her to read the same books as me, but she’d be tidying up after Jay, or straightening out her room, sewing a button on someone’s jacket. Always busy but never with the important things. Never outraged at a news story, or delirious with joy when a dictator had been overthrown, or even about something stupid, like winning fifty quid on the lottery.

‘Oh, Farah,’ I whispered, picking up the photo, rubbing my finger over the frown on my face as if that’d wipe it away.

Why does no-one understand that I wanted more for her? After all, isn’t that what sisters are meant to do? Want great things for each other? I turned my attention to my sculpture again, pleased with what I was in the middle of creating. This was going to wow people. I just had to get it right. It would be spectacular. I shook my head at my family and their ways. No-one understands: there’s nothing great about mediocrity.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_b83b0236-d202-5c83-b53b-0fc476cdfab3)

Farah (#ulink_b83b0236-d202-5c83-b53b-0fc476cdfab3)

House cleaned? Check. Shopping done? Check. Shopping delivered to Mum and Dad’s, along with money from Jay, that’s not actually from Jay but me? Check. I needed a minute and ended up collapsing on the sofa. Bubblee’s face swam in front of me even though I tried to blink it out of existence. It shouldn’t bother me – it’s been five years since I’ve been listening to the same passive-aggressive tone. I suppose you just don’t get used to your twin’s disappointment. The doorbell rang. It was Pooja who came to give back the electric screwdriver she’d borrowed.

‘Have you seen the monstrous boutique they’ve opened up on Henway Road? The designs of the Indian suits are awful. And you know our neighbours will be queuing up to buy some if there’s a South Asian wedding within a ten-mile radius.’

I smiled and gestured for her to come in but she said she had to go and make sure her husband didn’t feed her children Tuc biscuits for dinner.

‘Oh, an email’s gone around to confirm our meeting. You’re okay with next week?’ she asked.

There was a burglary a few months ago and we’d set up a neighbourhood watch as a result.

‘Yes, that’s fine and let’s have it at mine. I’ll respond to everyone.’

‘As long as we don’t ask Marge to bring snacks, because honestly, I don’t think I could stomach it,’ said Pooja.

I laughed and told her I’d delegate with that in mind as she said goodbye. Since I was up I checked whether Mustafa had paid the bills I’d found a few weeks ago. They all still needed to be paid. I picked up my mobile.

‘Hey,’ I said to Mustafa.

‘Hon, listen, I’m on my way to an important meeting. I just know this idea’s going to be the one,’ he said.

Which is what he said last time, and the time before that, and the time before that. I’d told him before that I knew this company was his dream – a place where he and his associates would get together and think about new inventions and apps – and then try to create them. But all the money he made in the stock market, coming out of university, was being used up in this company to no avail. Still, it was his money, and he still traded, which gave us a comfortable life, so I couldn’t complain. There was just no nice way of saying that his ideas were … not good. I didn’t want to be the cynical wife, though, because maybe, just maybe, he’d surprise me. And it would make me happy to see him happy.

‘I’ll call you in a bit, okay?’ he said, sounding distracted.

‘I just needed to know when you were transferring that money into our joint account. You still haven’t paid those bills, so I thought I’d do it.’

He paused.

‘Today,’ he replied.

‘Babe, that’s what you said last week. And the week before that.’

I included the ‘Babe’ to stop myself from sounding like a nagging wife. I waited for him to speak but it took a few moments.

‘I know. I’ll sort it out today. I promise,’ he added. ‘Are you okay?’

‘Yeah, fine.’

‘What’s wrong?’ he pressed.

‘Nothing,’ I said, then lost the will to pretend. ‘Bubblee.’

‘Oh.’

Why didn’t she see that despite the fact that this man’s been shunned by her, he still manages to bite his tongue when her name’s mentioned. But I suppose rage isn’t his thing. It’s neither of our thing. That’s what I love about him.

‘How is she?’ he asked.

‘Still Bubblee.’ I sighed and took out the groceries from the bag, putting them on the kitchen counter. ‘I thought going to London might soften her a bit.’

He laughed. ‘For a born-and-bred Britisher, you don’t have a very good idea of what London’s like.’

It still amuses me when he says ‘Britisher’.

‘You’ll transfer the money then?’ I said, suddenly feeling tired from having to talk about Bubblee.

I don’t need her to understand my marriage to Mustafa – I understand and so does he and that’s all that matters. I waited for him to respond. Five years with a person can help you to read their silences and hesitations as well as the intonation of their speech.

‘Is everything okay, Mustafa?’ I asked.

I just had to check – his silences weren’t normal. I don’t see how things couldn’t be okay. We had everything, after all. I looked around the house and the lack of toys cluttered everywhere; no playpen, no children’s books, no pieces of Lego or dolls left lying around. I hear people complain about what their children have or haven’t done and it stirs something inside of me – making me want to shout – not sure what I’d shout, but that doesn’t matter.

‘Everything’s fine, Far,’ he added. ‘I’ll always look after you. You know that, don’t you?’

Of course he will. He always has.

‘Have you heard from Jay lately?’ he asked.

‘He emailed last week. Why?’

‘Just wondering,’ he said. ‘I er …’ he paused. ‘I promised your parents I’d get him to help out with work. Just to give him a hand.’

‘Oh.’

It was the first I’d heard of it. Why hadn’t anybody told me? When I asked Mustafa he simply said that it was only bits and pieces Jay was doing – nothing major.

‘I’ll see how he gets on – it’s nothing permanent.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘For helping him out.’

‘You’re happy with it?’

‘I know it’ll mean a lot to Mum and Dad. But take it one step at a time with Jay. I love him but it’s not exactly an ideal plan.’

‘Yeah, yeah, of course.’

‘And come home early tonight if you can,’ I added.

He replied that he would as he put the phone down, when the doorbell rang again.

‘Hi, Abba,’ I said as Dad walked into the living room and switched the television on.

‘Your amma thinks I’ve gone out to buy some things for the garden,’ he said.

He settled down on my large white sofa, giving a satisfied sigh and smiled as The Arti-Fact Show flashed on our fifty-inch screen.

‘I’ll make the tea,’ I replied, glancing at the television screen. ‘The presenter’s put on weight, hasn’t he?’

‘Look at that,’ said Dad, observing what can only be described as a painting of a swan, studded with crystals. ‘Beautiful. Even your amma would like that,’ he added, turning to me, and possibly seeing the disgusted look on my face.

I gave him his tea with a slice of cake and sat down next to him.

‘You’re okay?’ he asked, not taking his eyes off the television screen.

‘Yeah.’

‘Bubblee’s ideas are different,’ he said, sipping his tea.

I picked a bit of walnut off my cake and put it to the side.

‘London,’ Dad said, shaking his head. ‘Everyone talks about London, but we are happy here, aren’t we?’ he added, putting his arm around me, squeezing my shoulders.

‘Yes, Abba.’

‘She’s a good girl, but if she could just get married so your amma would stop worrying, it would help me very much. Now your brother, on the other hand; we might not always see him but he still thinks of us, sending us money. Plus, you know boys will be boys.’

It was useful to have the TV as a distraction, because the look on my face might’ve given my secret away. I couldn’t quite bear the idea of Mum and Dad thinking that their only son’s one redeeming feature of sending them money was actually me.

‘Before I forget,’ said Dad, taking out a letter. ‘What is this?’

I read through it.

‘It’s just about parking meters. You can read, Abba.’

‘Yes, yes, but the English sometimes is confusing.’

‘It’s nothing,’ I added. ‘Won’t affect our road.’

‘Very good.’ Dad smacked his legs with his hands and got up to leave.

‘Don’t forget to get the soil that’s on offer, Abba,’ I said. ‘Not the full-price one. Mum won’t stop telling me about it otherwise.’

He nodded, gratefully, kissed me on the head and left. When he’d gone I wandered around the house. I do this often; when all the chores are done and the kitchen and bathroom can’t get any cleaner. I look at the high ceilings and arched doorways, the mowed lawn, with flower beds dotted all around. Mum used to tell us that a woman makes a house a home. But sometimes these spaces seem so empty I’m not sure what else I can do to fill the void that seems to stretch. There are potted plants in the home, picture frames and even some organised clutter I’ve arranged, but nothing fills the emptiness apart from when my husband comes home.

I remembered the day we moved into this house. I couldn’t believe we’d be living in a place so big and beautiful, but thanks to Mustafa’s job and some help from Mum and Dad we were able to afford it. There’s nothing quite like making your own home; filling up the spaces with things you’ve been given or have bought; deciding where to put the television; disagreeing over the paint, only to settle on a colour that looks dangerously close to Magnolia. Mustafa had come up behind me and put his arms around me.

‘Do you like it?’ he asked.

‘I love it,’ I replied.

‘The small room upstairs would make a perfect nursery, wouldn’t it?’ he added.

I shook myself from the memory and sat at my laptop, looking at baby items on the Internet. If I had a baby girl I’d dress her up in pink – I don’t care what people say about the colour; it’d look beautiful on her. And my boy would be in blue. I’d want the girl first so she could play me to our baby boy, who’d obviously have some of his Uncle Jay’s looks. She’d hug him when he fell over, cover for him whenever he got in trouble with me or Mustafa – she’d call him when we asked where he was before he’d come stumbling home, careful not to wake us. Before going to sleep he’d creep into her room and plant a kiss on her forehead, which she’d accept before hitting him on the arm for making her lie again. I laughed at the memory it conjured and missed Jay so much, I wished he’d visit us. Five years ago it would’ve been Bubblee I’d have gone to, but now he’s the only one I could tell: No, Jay. I can’t have babies.

I looked through my inbox and clicked on his latest email to me.

From: Amir, Jahangir

To: Lateef, Farah

Subject: Hi

Hi Sis,

Thanks for sending through that money again. You know how much I appreciate it. I promise I’m trying to get my life together. Sometimes it’s hard, but this time I really think I’m going to get my big break. I’ve a friend who’s got a business plan and he wants me to be a part of it.

Don’t tell anyone about it yet, not until it all goes through. I know it’s been a while since I’ve called Mum and Dad but I promise I’ll do that too. I’m just concentrating on this business plan.

Take care,

Jay

P.S. I do know how I’m lucky to have a sister like you.

God, please let this work. At least he did call Mum and Dad, even if it was five days later. I’d asked him what this plan was but he didn’t want to go into detail because he said he’d jinx it. I don’t know why it is that for some people things just don’t seem to go smoothly. It’s always been something with him – whether it was school or work. I prayed that next time he emailed, it would be good news.

I ended up falling asleep on the sofa. When I awoke it was already six o’clock and Mustafa wasn’t home yet so I called him. No answer. Whenever I get up from a nap I feel anxious – as if I’ve missed something while I was asleep. I need to stop looking at Internet sites for baby clothes.

‘Right – dinner,’ I said to myself.

Adding the tomato puree to the fried onions, I glanced over at the clock. Six thirty-five. As the chicken simmered in the pan I reached for my mobile and called him again, but it went straight to voicemail. When it got to seven-thirty the demeanour of easy-going wife began to slip. I checked our joint-account balance online and saw no money had been transferred.

Why doesn’t he just tell me when he can’t do something? Why does he have to lie? But the anger dissolved as I looked at the dinner that was getting cold. That’s when the doorbell rang.

‘You’re late and you forgot your keys,’ I called out as I opened the door.

I looked up at two young men in police officers’ outfits.

‘Mrs Lateef?’ one of them said.

What had happened? Had there been another burglary on the street?

‘Yes?’ I replied.

‘Is there anyone home with you?’

I shook my head. Just then Alice from next door was coming home and stopped to look at what was going on.

‘Everything okay, officers?’ she asked, walking over.

‘Is this lady a friend of yours, Mrs Lateef?’ asked one of the officers.

‘Yes, I am,’ replied Alice.

The police officer gave a constrained smile as he looked at me for confirmation. I nodded.

‘What’s going on?’ I asked.

I didn’t know why but a knot formed in my stomach as I gripped the door handle.

‘It’s your husband,’ one of them said.

I couldn’t quite focus on their faces as my heart began to thud so loudly it muffled my hearing. Their image became a blur.

‘I’m afraid he’s been in an accident.’

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_b2e82b79-b08d-5584-bdd0-ab2bcbcc9345)

Mae (#ulink_b2e82b79-b08d-5584-bdd0-ab2bcbcc9345)

‘Mae, put the camera away,’ Fatti whispered into my ear.

Was she mad? This was prime videoing time; all these faces, the hospital, the tension.

‘Put it away or I’ll throw it in the bin,’ exclaimed Mum.

Everyone in the waiting room looked at Mum. Didn’t look like she cared. I tucked the phone under my leg as Dad gave an exhausted sigh. Fatti got up and made her way towards the door, outside, where Farah was sitting on her own. Looked like Dad was lost in a world of his own, so I got up and walked towards the door too with my phone. I’d just got a message from the girls from school.

Omg. Jus saw on your snapchat that your bro inlaws been in an accident. Are you alright?? Hashtagged on Twitter #Pray4family. Lemme know if you need anything. Xxx

I knew it wasn’t ideal to video all of this but it was my GCSE assignment. Plus, it’s weird how people find my family so interesting. Whenever I put something on Snapchat about them it always gets loads of hits, because some people appreciate creativity – and not the Bubblee kind, but the real, gritty, my-generation kind. What my fam fail to understand is that they don’t actually have peripheral vision. Yeah, in the literal sense they have it, but not in the metaphorical sense (I’m going to ace my GCSE English too). For example, as I walked up to the door, Mum and Dad in the waiting room couldn’t see how Fatti looked, sitting next to Farah. I sneakily got my phone out again. Of course Farah’s going to be crying and all sorts but when I zoomed in on Fatti, just a little, there was something more than upset there. A look no-one would’ve noticed if it weren’t for me and my trusted camera.

The doctor came and paused in front of Farah and Fatti as they both looked up. She started saying something about Mustafa being in a medically induced coma.

‘A coma?’ said Farah, looking confused.

‘It’s just a precaution to avoid nerve and brain-stem cell damage that can be caused by the swelling of the brain,’ she said.

‘But he’s going to be okay, isn’t he?’ said Fatti. ‘I mean, he’s going to come out of it.’

The doctor removed her glasses. ‘It’s too early to tell. The injuries to the head have been severe. We’ll have to wait to see the extent once the swelling has reduced and we take him out of the coma.’

‘Oh, God,’ said Farah, clutching her stomach.

‘So, the coma’s not permanent?’ said Fatti.

‘No, no. Just temporary and reversible.’

Farah shook her head. ‘I told him,’ she said to Fatti. ‘Always use your head-set. You’ll get caught by the police. You’ll have an accident.’

I felt a lump in my throat but pushed it back. Fatti rubbed Farah’s back, not saying much. She did look a little slimmer at this angle.

Every1s asking what’s goin on with ur bro-in-law. U should tweet sumthin.

I tweeted:

Bro-in-law in coma. In hospital with amazin staff.

#Pray4Family

‘Who was he speaking to?’ asked Fatti.

Farah shook her head. ‘Don’t know. His phone’s dead—’

She stopped and did this weird staccato intake of breath as if she’d forgotten how to breathe. I realised only then that I didn’t think I’d ever seen Farah cry. Fatti cries all the time. I know because I sometimes hear her in her room. All it takes is me offering her a salad before her eyes fill with tears. Bubblee cried the day she said she was moving to London. Those were more tears of rage, though. What a drama that was. I should watch that video back one day – ‘You’re stifling me! We’re human beings, not just girls who are made to get married and churn out babies …’ On and on it went.

Fatti took Farah into a hug and I zoomed in on Fatti’s face again, looking so sad and sorry that I decided to switch the camera off. Though I did wonder: what’s she got to be sorry about?

When Bubblee came running down the corridor, Farah looked up as if she couldn’t believe her eyes. Bubblee slowed down to a walk as she approached us and took the seat next to Farah. When I was a child I used to pretend that Farah and Bubblee were the two ugly step-sisters (except they weren’t ugly, obvs) and Fatti was my fairy godmother.

‘You came,’ said Farah. Not like she sounded grateful or anything – just surprised.

Bubblee gave a tight kind of smile. Smiling never did come naturally to her.

‘What do the doctors say?’ Bubblee asked.

‘Severe head trauma,’ replied Farah, pressing her hand to her forehead.

I couldn’t help it. I had to get my phone out again. I put it on video and then tucked it into my shirt pocket so it recorded everything without anyone going, Mae, turn it off. Mae, stop it. Maeeeeeee.

‘But what does that mean?’ asked Bubblee.

Farah looked at her. ‘It means they don’t know if he’ll make it.’

‘Oh,’ replied Bubblee.

‘He’ll be okay,’ added Fatti. ‘You’ll see. He’ll be just fine.’

Unlike Fatti’s eating habits, her voice is kind of even. Some might say it’s monotone – they’re people who have a problem with consistency – but right then her voice had a note of panic.

‘Why are you being so weird?’ I asked her later when she got up to use the bathroom.

‘Am I? No, I’m not.’

She looked at herself in the bathroom mirror.

‘It’s not that bad,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘Your face,’ I replied, laughing.

She sighed. ‘You should go and sit with Farah.’

‘And say what? Sorry your husband’s in a coma?’

‘Mae.’

Fatti closed her eyes and splashed her face with some water. The problem with Fatti is that she’s a worrier. Every little thing will have her crease her eyebrows, look from side to side and probably throw up.

‘Poor Farah,’ she said, under her breath. ‘She doesn’t deserve this,’ she added, looking at me.

‘You’re telling me.’

‘And Mustafa. Lying there with all those wires going through him, not having a clue that his wife’s crying her eyes out.’

I squirted some disinfectant soap and rubbed it into my hands.

‘He’s too nice to be in a coma,’ she added.

‘Yeah, well, it’d be great if only murderers and rapists got put in comas, but I don’t think that’s how it works.’

She paused, leaning against the sink. ‘Did you finish your history homework?’

‘Not exactly top of my list of priorities right now,’ I said.

‘You’ve had all week. You’ve got subjects other than media and English, Mae.’

‘Have I?’ I said, leaning forward in shock as if I’d just found this out. I leaned back and rolled my eyes. ‘Don’t know how I’d keep up if it wasn’t for you.’

Fatti dragged me by the arm as we came out of the bathroom and sat me down in the waiting room.

‘My poor daughter,’ said Mum. ‘My poor sister.’

I glanced at Fatti as Bubblee walked into the room. ‘Has anyone called Mustafa’s mum to let her know?’

We all looked at each other. No-one had enough of their head about them to actually call Mustafa’s mum in Bangladesh.

‘She won’t forgive me,’ said Mum.

Bubblee sighed and got her phone out. ‘You didn’t drive into him, Amma. What’s her number?’

‘No, no. I’ll call her myself.’

With which Mum got her special calling card out and left the room. Dad got up a few moments later and followed her out of the room.

‘Amazing, isn’t it?’ said Bubblee. ‘Her sister’s son is married to her daughter and they still only speak to each other once every few months.’

‘Weird, for sure,’ I mumbled, scrolling through Twitter, reading all the messages I was getting about Mustafa.

Bubblee nudged me and looked over at Fatti who was wringing her hands. She’s mostly like a human but also a bit like a puppy – especially when she looks up at you like she did just then.

‘I don’t want Farah to be unhappy,’ she said.

Er, obviously.

‘Then you’d better stop looking like someone’s about to die,’ said Bubblee. ‘Because that’s the last thing Farah needs.’

*

We all came home that night – Bubblee volunteered to go home with Farah so she wouldn’t be sleeping alone. Mum, Dad, Fatti and I went to bed but when I got to my room and put my hand in my jeans pocket I realised I’d forgotten my phone, recording and propped up against the bread-bin in the kitchen. Walking past Mum and Dad’s bedroom, I heard them muttering. I’d have just walked past but something made me lean in and listen.

‘Did you see how short she’d cut her beautiful, long hair?’ I heard Mum say to Dad from outside their bedroom.

Amazing, isn’t it? Their son-in-law’s done in and in a coma, and Mum wanted to chat about Bubblee’s hair.

‘I spoke to Mrs Bhatchariya about boys for her. She said she’d send me some details, but you know what I think. We shouldn’t have let her go to London,’ added Mum.

‘Why couldn’t she be like our Faru?’ said Dad.

I was surprised they didn’t say Fatti. Nothing Fatti does is ever wrong. Speaking of the expanding devil, she came up the stairs and saw me crouching outside Mum and Dad’s door.

‘What are you doing there?’ she whispered, crouching with me.

‘Shh. I thought you’d gone to bed.’

‘Is that Mum crying?’ she asked.

I nodded.

‘Do you think Dad’s comforting her?’ she asked.

I let out a stifled laugh. ‘Yeah, right.’

Fatti began shifting on each leg until she couldn’t take it any more and sat back, leaning against the wall.

‘Why do you think that’s weird?’ she asked. ‘They’re always chatting in that room.’

‘Are they?’ I asked.

‘You might notice if you weren’t on your phone all the time.’

‘I only know what I need to know, thanks,’ I replied.

Fatti shook her head at me.

‘You think he’s going to be okay?’ she said.

‘Who?’

‘Mustafa.’

I shrugged. ‘Dunno. Hope so.’

‘What if he’s not, though?’ Fatti looked at me, fear in her eyes. ‘What if he … dies?’ Tears welled and were in danger of rolling down her cheeks.

‘You always think the worst’s going to happen.’

Fatti looked like she was about to say something when we heard Dad speak.

‘Malik is getting on a flight and coming as soon as possible.’

Our aunt and uncle are too old to travel and so their third eldest is coming instead.

‘Maybe this is why it’s all happened,’ said Mum. ‘Malik will come and then …’

Fatti struggled off the ground, interrupting my eavesdropping with her deep breaths and suppressed sighing.

‘Do you think Bubblee and Farah are okay on their own in Farah’s house? Maybe I should’ve stayed with her instead?’ she said as she hovered over me.

‘They’ll be fine. It’s not like they’ll kill each other – not while Farah’s husband’s in hospital,’ I replied.

‘You shouldn’t be eavesdropping,’ said Fatti, putting both hands on her hips.

I shooed her away. She was killing my buzz as I continued to listen in to my parents’ room, so she plodded away.

‘But is it the right time?’ said Mum.

Right time for what? I leaned in closer as they both went quiet. Then Dad spoke.

‘It doesn’t matter that he’s coming. Mustafa is here and you never worry about it.’

‘Mustafa is different. He’s the same as us now,’ said Mum. ‘Maybe Malik will also be like us one day. It will be the answer to our prayers and then we could tell her.’

‘We’ve waited very long,’ said Dad.

What were they talking about? Annoying Fatti who made me miss half the conversation with her anti-eavesdropping morals. Before I knew it, Mum and Dad began talking about shopping that was needed and how Farah should stay with us while Mustafa’s in hospital. Then I heard the creaking of the bunk as they both seemed to get ready to sleep.

I went downstairs to get my phone and switched off the recording. Before I deleted it I thought I might as well check what it had caught and, sure as anything, there was Fatti, stuffing her gob with mashed prawns and cream cheese.

*

‘Has someone tried to call Jay?’ asked Bubblee. ‘Farah’ll want him to know.’

I looked at Fatti. Fatti looked at me. It hadn’t occurred to any of us that he should be told, given that he never knows what’s going on in the family anyway. Mum and Dad were walking down the hospital corridor where we’d congregated. Farah was in Mustafa’s room. When we asked them, Dad said: ‘No, no. Better to keep him out of it for now.’

‘He’ll just worry,’ said Mum. ‘Such a busy boy, trying to make something of himself.’

Bubblee scoffed as she folded her arms. Mum looked at her and raised her finger, while Dad mumbled something about needing some tea. It’s not as if Bubblee actually said anything, but God forbid anyone even suggest that Jay’s a waste. Which, as the youngest, I can appreciate without feeling too bothered about it. Bubblee’s bothered about everything, though. It’s just who she is.

‘Your amma is already worried enough. Don’t worry her more,’ said Dad to Bubblee. ‘And she isn’t wrong.’ He looked towards Mum who was staring at him. ‘You’re getting old and must think about getting married. Look at Mustafa and think how things can turn out.’

It’s not like he raised his voice or anything, but it was a bit off-topic.

Even in the middle of a hospital Asian parents have to speak about marriage. #Obsessed #Marriage #Coma.

Bubblee went to protest but Fatti nudged her as Mum looked at her.

‘Our son is trying to be a man,’ she said. ‘You should try to be a woman.’

Dad looked at the ground and followed Mum as they both walked away, leaving Bubblee, basically bubbling with anger. Who can blame her? I mean, bit harsh telling her that the only way she’s a woman is if she gets married. Plus, what did that make Fatti, who’d turned a shade of red too when Mum said that. Our amma needs to get with the programme. Can’t fight these oldies though, they’re stuck in their ways. Shame, really. Mum’s all right when she’s chilled out and not worrying about the fact that Farah’s not had a baby, the rice has run out or that Bubblee’s not married. She’s even interesting when you listen to the stories she tells about her childhood.

‘Unbelievable,’ Bubblee exclaimed as soon as they were out of earshot. The nurse behind the desk shot us a look. ‘Our brother-in-law’s in a coma and all Mum can think about is me getting married.’

I think it was a good idea to have a hidden camera running – you have to love media equipment. This would’ve been the time I’d have had to switch it off otherwise. Fatti fidgeted with her hands. I put my arm around Bubblee.

‘You’re twenty-eight, Bangladeshi and single. What else are they going to think about?’

Bubblee looked at me as if she was about to tell me to go to my room, before glancing at Fatti.

‘I don’t understand why they’re not on your back,’ she said to Fatti, shrugging my arm off her shoulder. ‘You’re two years older than me.’

‘Mae, go check if Mum’s okay,’ said Fatti to me.

‘You check,’ I replied.

She gave me her fairy godmother look so of course I had to listen. I swear, being the youngest in the family sucks.

‘All right, Ma?’ I said, slouching in the seat next to Mum and resting my arm on her shoulder.

‘Mae – sit like a girl.’

‘Oops, sorry,’ I said, putting my hands in the air before crossing my ankles. I pointed at them to show Mum how careful I was with her instruction. She ignored me. I tell you, it takes some kind of resilience to put up with this stuff.

‘So, er, Jay,’ I said.

‘Tst, Jahangeer,’ pronounced Mum. ‘We give him this beautiful name and you spoil it.’

Talk about touchy.

‘He’s the one who prefers it,’ I replied. ‘He hates his name. Jahangeer. Jahangeeeeeer,’ I said, spreading my arms out in dramatic Bollywood fashion. I sat back after Mum slapped my leg. ‘I mean, who can blame him?’

She chose to ignore this before she said: ‘Go and see where your abba is.’

‘But I want to talk to you, Amma.’ I gripped her shoulders and shook them. ‘See how you’re feeling, talk about what’s going on in here,’ I added, patting her bony chest.

She didn’t brush my arm off, so that was something. Mum stared at the wall in front of us that had disaster warnings of AIDS and Meningitis and all the diseases under the Wyvernage sky.

‘You girls don’t understand the struggles we’ve gone through.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘You know how easy your life is?’

I wanted to say easy’s not the word I’d use, but best not to rattle cages in hospitals and all that. Mum turned to me, her eyes softening. If I could’ve angled my video camera right then I’d have focused on those eyes.

‘You were such a good baby.’

This had me straighten up in my chair with pride.

‘And then you started speaking,’ she added. ‘Every time I would tell you to be quiet, Fatti would take you and talk to you.’ She smiled at the memory. ‘Oh, I forgot to tell her I brought some of her cheese for her.’

She rummaged in her handbag to look for it, found it and put it carefully in one of the bag’s pockets.

‘Now check if your abba is fine,’ she said finally.

‘All right then. Good talk, Mum.’

I lifted myself off the chair and went in search of Dad who was standing in front of the vending machine, looking a little hard done by.

‘Every time,’ he said. ‘You put in money and nothing comes out.’

I nudged him out of the way and grabbed both sides of the vending machine, shaking it. That didn’t work so I bent down and shoved my arm up to get hold of his packet of Maltesers that had got stuck between the Bounty and M&Ms. It was too far up for me to reach. I saw him shaking his head at me. With one last try I flung myself at the machine, hitting it with my arm, and out fell the Maltesers.

‘You’re welcome, Pops,’ I said, handing him his packet of e-numbers.

He looked at the packet, turning it around in his hands. ‘You know, sometimes your amma is a little harsh.’

‘No kidding,’ I said.

‘But it’s only because she wants the best for you girls,’ he added, shaking his Maltesers at me.

He handed them to me and said: ‘Now go and give these to Faru.’

I sighed and walked down the quiet, grey corridor, cleaning my hands at one of the hand sanitisers attached to the walls. Farah was sitting on the green leather chair, next to Mustafa’s bed, staring at him.

‘Hey,’ I said, looking around for Bubblee and Fatti.

I opened the packet of Maltesers and handed them to her. She put them on her lap.

‘How’re you doing?’ I asked.

She nodded. What did that mean?

‘You’ve got to hope for the best,’ I said, looking at Mustafa.

I wanted to prod him, just to see what reaction, if any, I’d get from him: would he twitch? Give a deeper intake of breath? Just stay motionless? But I don’t think Farah would’ve been too happy about that. I’d have been accused of not taking anything seriously. It’s just that, granted he wasn’t dead, but he wasn’t exactly alive either, was he? It was kind of fascinating – all of us watching a man in limbo.

‘Jay’s the one who calls himself Jay, isn’t it?’ I said.

She looked at me. ‘What?’

‘Mum goes on at us as if we’re the ones who’ve spoilt his name.’

She looked at me like: What the hell are you talking about? ‘Has he called?’

‘No, I mean he doesn’t like being called Jahangeer, does he?’

She looked at me, confused, but I was just trying to make conversation that didn’t have to do with Mustafa.

‘Mae – go and see if Mum and Dad are okay.’

You’ve got to wonder, don’t you? Who’s making sure I’m okay? So I took out my phone and decided to check my Twitter account – and what do you know? I got thirty-two new followers.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_645c570b-ddfd-5134-ab77-ef3b3aaa81b8)

Fatima (#ulink_645c570b-ddfd-5134-ab77-ef3b3aaa81b8)

Oh God, oh God, oh God. Was it my fault? I looked up at the sky, in case I got a sign whether it was or not. Did I give my sister the evil eye? It’s not as if I wanted to marry her husband – just that, what would it be like to come home to someone who loves you? What’s worse is that I can never stop my tears from falling and everyone looks at me like I’m this pathetic person. How do you make yourself disappear? So you can feel what you feel without worrying about what other people see?

When we got home after the second day at the hospital Mum and Dad insisted that Farah come and stay with us – we’d all be together under one house, just like old times.

‘Apart from Jay,’ said Mae without looking up from her phone.

‘Look at this,’ said Bubblee, picking up the local newspaper. ‘Front page news.’

She skimmed through it and dropped it on the table. Mae went to read the article.

‘Car accident leaves old lady’s prize-winning poodle in need of veterinary care.’ Mae laughed. ‘The victim …’ She looked up. ‘… That’d be our bro-in-law – is in a coma. He is thought to be in a critical but stable condition.’

‘This place,’ said Bubblee, shaking her head. ‘A poodle’s disturbed and it’s front-page news.’

‘Marnie was complaining about the traffic on Bingham Road because of the branch that fell from the tree,’ added Dad.

‘That’s Mrs Lemington,’ I said. ‘She loves her dog. We should probably send her something.’

Farah stared at the page and didn’t say anything.

‘Animals matter more than humans here.’ Mum shook her head as she went straight into the kitchen and I followed her to help prepare dinner for everyone. Bubblee loomed in the doorway.

‘This is just typical.’

How does she manage to fill a room like that without being fat? I always seem to fill it in the wrong way – not knowing where to put myself – where to shift or pause. But not Bubblee. She enters a room and people have to look. You can’t not look at beauty: her brown hair, chopped and cut messily; her big eyes darting between Mum and Dad; rose-bud mouth pursed in her usual annoyed way. All this and living her independent life in London, not being tied to what people tell her; knowing what she wants and then just going out to get it. It’s almost as if she knows she has a right to it. Or at least a right to try. I suppose everyone has that right, but how do some people just feel it? I’m told she and I have the same eyes, but I don’t see it. I see nothing of myself in any of my sisters.

‘When was the last time Dad entered the kitchen?’ Bubblee added, putting down her patchwork bag that bulged at the seams.

She walked in and I had a sudden feeling of the room being too full, a need to be in my own space, within my four walls.

‘Is this how you’ll speak to your husband when you’re married?’ said Mum, looking at her. ‘You should go and borrow some clothes from Faru. I’m not letting a boy see you like that in such tight jeans and T-shirt.’

‘What boy?’ said Bubblee as I got the ghee out of the cupboard.

‘You’ll see him tomorrow,’ replied Mum.

Tomorrow! I remembered. I had a hand-modelling shoot tomorrow. When I told Mum that I’d cancel it she said: ‘No, no, no. You must still go. I want to add it to my pile.’

She opened her drawer to show the plastic wallet she has of all my hand-modelling pictures.

‘Bubblee will drive you.’ She looked over at her. ‘And you’ll wear something nice when you both come after to the hospital.’

‘No, I won’t,’ answered Bubblee.

‘Bubblee – for so long your dad and me have let you do what you want. Do you know the talk we have to hear when people know you live in London?’

Why don’t my parents ask me about marriage? Do they think I’m too fat and unattractive to be married? They wouldn’t be wrong, but aren’t your parents at least meant to see the best in you? Isn’t that the point? Dad was standing behind Bubblee. She didn’t see him until he said: ‘Malik.’

Bubblee turned to look at him.

‘Your amma and I have talked about it and we think it would be very good if you married him.’ He glanced over at Mum who was staring at Bubblee, a frown etched in her brows.

I opened the can of ghee, trying to concentrate on the sizzling onions, trying to forget that Malik – last I remembered – was thirty-two. Only two years older than me – wasn’t that the perfect age for me? I reached into the cupboard and got the cheese tube out, squirting it in my mouth while they weren’t looking.

‘But I don’t even know him,’ Bubblee exclaimed. ‘Anyway, I have to go back to London tomorrow. Sasha has an exhibition and I promised I’d be there.’

Mum adjusted her purple sari and lit the hob. ‘Sasha is not more important than your family.’

‘You shouldn’t spend so much time with just one girl,’ said Dad, clearing his throat. ‘Please, Bubblee,’ he said, taking her hand. ‘Open your mind that you might like something that your parents think is good for you. Why would we want to see you unhappy?’

‘But I’m happy now,’ she replied.

Mum and Dad were both turned towards Bubblee – me hovering in the background, frying onions. I wondered: what does happiness really feel like?

*

The following day everyone else went to the hospital as Bubblee drove me to my shoot. She’d given in and worn a pair of jeans with a kaftan, which made me think that sometimes she could do things, against her principles, just to keep the peace. She’d called Sasha and let her know she wouldn’t make her exhibition.

‘And no-one appreciates it,’ she said to me, one hand gripping the steering wheel and the other resting on the gear-stick. ‘That I’m putting my life on hold. It’s all expected.’

Weird how she didn’t expect it of herself.

‘Farah needs us all here,’ I said.

She took a deep sigh. ‘I know, I know. God, there’s no need to make me feel worse than they do. It’s just Mum is impossible and Dad nods at everything she says. It’s infuriating.’

‘At least it’s not the other way around,’ I replied.

Let’s face it, Bubblee would’ve been up in feminist arms.

‘Doesn’t make much difference, given that Mum’s intent on ruling my life and telling me what to do. All because it’s expected that I’ll get married. It’s expected that I’ll be a good little wife.’ She beeped at someone, who I’m pretty sure had the right of way. ‘Like good old Farah.’

We all know that Bubblee’s ideals – however weird they seem to me – stop her from liking the fact that Mustafa married our sister, but I never understood the strength of her opposition to it. It’s not as if we get to like everything in life, but we accept it and get on with it. There are a thousand and one things I’d change about mine: not having a driver’s licence being one of them; losing weight; being able to walk into a room with the same confidence that all my sisters seem to have. I might cry about it in my own room but I don’t make a song and dance about it to everyone – how uncomfortable would that be? There are some things that you just keep to yourself.

‘Did something happen?’ I asked her.

‘What do you mean?’

‘For you to hate Mustafa so much.’

She paused at a traffic light. ‘I don’t hate him. He’s fine.’

‘Then what is it?’

She looked at me like I was an idiot who’d missed the point completely. ‘Why did Farah settle for fine? All this playing house is so … conformative.’

I didn’t really understand what she meant by playing house. I thought that was just life – you meet someone, you fall in love, then you marry them. Wasn’t that just being happy?

‘God, I hope Mae doesn’t do the same,’ she added, picking up her phone, checking for messages then throwing it back down. ‘What another waste it’d be.’

‘Is that what I am?’ I mumbled.

It wasn’t meant to come out loud at all, but somehow the words tumbled out. I hoped she hadn’t heard them.