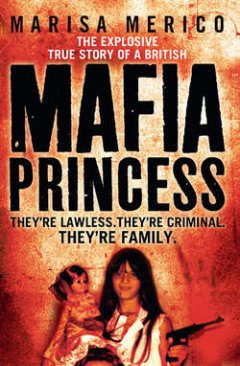

Mafia Princess

Àâòîð:Marisa Merico

Æàíð: èñòîðè÷åñêèå äåòåêòèâû

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:229.39 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 465

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 229.39 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Mafia Princess

Marisa Merico

Marisa Merico, the daughter of one of Italy's most notorious Mafia Godfathers, was dazzled by her father, Emilio DiGiovine. To her he was all powerful, sophisticated and loving; to the rest of the world he was staggeringly ruthless. Marisa knew her father would do anything for her, but she hadn't expected just how much he would ask in return.Born to an English mother, Marisa turned her back on her quiet life in Blackpool to join her charming father, Emilio DiGiovine, who had spent years trying to tempt her back to Italy. Arriving in Milan, Marisa had no idea she was returning to the heart of one of the most notorious drugs, arms and money laundering empires in the world.At first her father shielded her from the family operations and Marisa was overwhelmed by the attention and gifts he lavished on her. But soon the temptation of a new recruit was too great and Marisa was drawn ever deeper into the family's sinister and brutal regime, witnessing things she was too scared to believe.The day she eloped with her father's chief henchman was the day her father decided she was ready to be initiated into the true nature of the family business. Suddenly Marisa saw there was no limit to what he would expect her to do for him. She knew it was wrong, she knew she had to get out, but she had no idea how she could break the sacred Coda Nostra – and survive.Marisa's extraordinarily story is the most powerful portrayal of a Mafia family to emerge in recent years. It's the perfect balance of shocking violence, dangerous betrayals and enduring love.

Mafia Princess

THEY’RE LAWLESS.THEY’RE CRIMINAL.

THEY’RE FAMILY.

Marisa Merico

with Douglas Thompson

FOR LARA AND FRANK

‘The family – that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape nor, in our inmost hearts, ever quite wish to.’

DODIE SMITH,

I CAPTURE THE CASTLE, 1948

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat:

‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat. ‘Or you wouldn’t have come here.’

LEWIS CARROLL,

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND, 1865

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u7249a9e0-c0a9-5378-8e98-156d7d39d303)

Title Page (#ucf645041-953e-5468-8841-83f6ac204de2)

Dedication (#u73a9af8e-978c-5302-8b9b-948c3eee32d2)

Epigraph (#u7b61200d-a903-51c1-8950-f34502f735f8)

FOREWORD (#u1975bfb0-1499-5f4f-b228-aa84dc66a4b3)

CHAPTER ONE GUCCI GUCCI COO (#u07110d1a-fa24-5064-a2f1-44e0e2d4efa7)

CHAPTER TWO WONDERLAND (#u899540c5-e014-59f7-917a-79f309f1ab44)

CHAPTER THREE MARLBORO WOMAN (#u3a1fa8c8-17b2-57cb-9e8f-d6a3d70c710d)

CHAPTER FOUR ROOM SERVICE (#u5bf46538-39da-5fc2-bb8d-52c6c7d51cce)

CHAPTER FIVE GUNS AND ROSES (#u012d240c-358d-5e71-b8a5-e2979ced3c08)

CHAPTER SIX COUNT MARCO AND THE DAPPER DON (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN THE GOOD LIFE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT ROMEO (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE STREET JUSTICE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN MAFIA MAKEOVER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN CAT AND MOUSE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE BETTER OR WORSE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN LA SIGNORA MARISA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN RAINY DAYS IN BLACKPOOL (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN WHO’LL STOP THE RAIN? (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN LA DOLCE VITA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN MEAN STREETS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN BORN AGAIN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN FAMILY VALUES (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY DREAMLAND (#litres_trial_promo)

POSTSCRIPT GUN LAW (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_ab616686-9c61-5484-a6b3-c0dfe2afdf10)

‘Dream as if you’ll live for ever, live as if you’ll die today.’

JAMES DEAN, 1954

They shot dead my godfather with a 7.63 calibre pistol as he sat in his favourite barber’s chair waiting for a wet shave.

An explosive bullet from a high-precision rifle blew the top off my dad’s cousin’s head as he left his house, in the hurried moment between his front door and his armour-plated car.

An uncle of mine was gunned down by automatic fire as he was serving wine in his caf?-bar one lunchtime.

Soon after, the man who issued the orders for these murders was killed while in protective custody, as he took his Sunday morning exercise in the prison yard. A marksman aiming from a building outside the prison walls put a rifled, explosive bullet in his forehead.

With nearly seven hundred combatants and innocents already dead, the violence was escalating every day and my family was suffering. Which was why, at the age of nineteen, I agreed to drive South with a consignment of military weapons packed into the secret compartments of the family’s customised Citro?n, the one that was usually used to traffic heroin.

We stacked machine pistols, handguns and rifles, clips of ammunition, bullet-proof vests and jackets on top of the heavier hardware: Kalashnikovs, those awesome AK-47S which can spray out 650 rounds a minute, and bazookas that toss armour-plated vehicles into the sky.

It was like packing your sweaters and skirts first in a holiday suitcase, having all the ironed stuff lying flat, your toilet bag and shoes stashed in the corners.

I was too young to understand the complexity of everything that was happening, and too dizzily in love with the boyfriend who came with me to feel scared – even when the carabinieri stopped for a chat alongside our car, where we had stashed away enough weaponry to start World War Three.

We didn’t have a fear in the world. It was just like going on a family summer holiday.

After our delivery, the war became even more intense. The rival families didn’t have the contacts to get military weapons like the Yugoslav bazookas we’d brought. Hit squads operated as four-men units: a driver, a shooter with a 12-gauge automatic Benelli, renowned in the lethal mechanics of urban warfare, two men with machine pistols. Russian RPGs, the antitank grenade launchers, were around. There were also arson teams to burn out the rivals who were taken down by rifle fire as they struggled to flee the flames.

Still it wasn’t all one way. Uncle Domenico – a lovely, lovely man, full of laughter and fun, my Nan’s brother, one of my favourite uncles – was shot dead as he strolled onto his bedroom balcony to smoke a cigar.

How many people have relatives who are shot and killed? I grew up with it.

These were insane times.

It was violence against violence and even then it was clear to me that the winner is the one who has the more homicidal equipment. And intentions.

I’ve learned such things for, even before I was born, violence was vital to my life.

It got me born.

CHAPTER ONE GUCCI GUCCI COO (#ulink_1f36e955-9ac6-5f5a-b264-80192e916e71)

Fidarsi ? bene, non fidarsi ? meglio.

[To trust is good, not to trust is better.]

ITALIAN SAYING

I was born on my Nan’s kitchen table. I emerged reluctantly, just in time for breakfast, in the middle room of her house in the Piazza Prealpi in Milan.

It was the same table on which my Nan had given birth to her twelve children, including her youngest, Angela, who’d arrived just four weeks earlier.

My mum didn’t have any contractions. She was taking her time to deliver me and Nan’s household wasn’t used to that.

‘Push! Push, push!’ Nan’s friend Francesca the midwife shouted at her.

Mum wasn’t pushing, not at all. She didn’t know what all the fuss was about. She was in a haze. She had no energy left. She’d been in labour for more than twelve hours.

‘Go on, push!’

Nan couldn’t understand the delay. When she’d given birth to Angela the month before, the production line had been as smooth as ever. This silly English girl on the kitchen table just didn’t have a clue how to have babies. Shouting wasn’t helping. The family had been up most of the night; they wandered around, yawning, trying to stay alert, but the coffee had stopped working hours before.

Now, at 8 a.m. on Thursday the 19th of February 1970, they’d had enough. Certainly my grandpa Rosario Di Giovine had. He wanted his breakfast.

‘Nothing’s happening, nothing at all,’ said Nan.

Grandpa rolled up his sleeve: ‘Right, come on! Come on, my girl…Vai! Vai!’

He gave Mum a real slap on the leg. Then another, harder, on the backside: ‘Come on – let’s have you.’

Mum pushed.

I arrived at 8.09 a.m.

Grandpa went off to eat, as if nothing had happened. My nan went to a cupboard at the side of the room. The midwife swaddled me in cotton cloths, and Nan returned with a purple cashmere Gucci blanket, a gift from an associate, and wrapped me up in it.

It was appropriate. I’d been born into the Mob. I was a Mafia Princess.

My mum didn’t have a lot of milk, so Nan breastfed me a few times. I loved my nan. I was always her favourite. Yet that Gucci blanket was no glass slipper. My early life was more like Cinderella’s before the prince came on the scene. And certainly no fairytale.

As I grew up, the family were ferociously pursuing their business, and that involved a great deal of guns and drugs and death. For my father’s family it had always been that way.

Nan was a pure bloodline Serraino, born in Reggio Calabria to one of the legendary ’Ndrangheta clans that make up the Calabrian Mafia. Pronounced en-drang-ay-ta, it translates as honour or loyalty, and loyalty to the family (or ’ndrina) is in the blood, flowing through their veins.

Nan can’t sign her name – she uses an X on documents – but she is one of the most remarkable Mafia figures of the past few decades, known widely as La Signora Maria, the Lady Maria. The authorities are ever so complimentary about her. I’ve seen Italian legal paperwork that ranks her the most dangerous woman in Italy.

I was named after her – Maria Elena Marisa (Di Giovine) – but people always called me Marisa; to avoid confusion, they said. Confusion? That was a good one. La Signora Maria is unique.

You don’t join the ’Ndrangheta; your membership is ordained. All Nan’s children knew the laws of such an indigenous and territorial Mafia family. They saw it as kids in Calabria, where my nan learned the gospel of violence first hand. People think that men run everything in the Mafia and the little woman isn’t even allowed to stir the pasta sauce. About half an hour’s sail across the Strait of Messina in Sicily, home of the Cosa Nostra, female roles were more like those you see in the movies, but in Calabria’s ’Ndrangheta, built for more than 150 years on the blood family, women have always been heavily involved in both the kitchen and the crime. There are even sisters in omert? – the Mafia code of silence. There are stories of initiation ceremonies for women not born into the family to be formally accepted. Blood relations and family ceremonies such as weddings, communions, christenings and funerals, are the core of the life. And death. There wasn’t ever a grey area with my nan. Nothing ambiguous about La Signora Maria.

She was the boss, the ultimate law.

And Pat Riley from Blackpool’s mother-in-law.

Mum was a stunner – blonde, shapely and fun to be around – but brought up in the suburbs of north-west England to be practical and sensible. Up to a point. She’s always been determined, her own person. The Blackpool Illuminations were never going to be the only bright lights in her life.

Patricia Carol Riley is a baby boomer, born on 17 January 1946, a little more than a year after her father, Jack Riley, returned from his wartime service in the ambulance corps. He and Grandma Dorothy had two more daughters, Gillian and Sharon. Granddad worked as a greengrocer, and Grandma had two jobs, one in a grocery store and another at the local Odeon. The long hours finally allowed them to buy themselves out of a council estate and into their own home for the sum of ?3,000.

A treat for the girls was salmon paste sandwiches and tea on the beach next to Blackpool Promenade. It was a good life but quiet, ordinary. There were never going to be any surprises. It’s easy to understand that it got boring for a bright teenager like my mum.

She has her artistic side, she has an ‘eye’. She’s absolutely brilliant at art. She’s got an ‘A’ level in it and could have taught it but her dad wouldn’t let her go to art college. He thought it would be a waste of time – a degree and then she’d be off to get married and have kids. He and my grandma just wanted husbands, not complications, for their girls.

Mum was fed up. She liked her job as a window dresser for Littlewoods in Blackpool but she felt she was going down a predictable road, which she had to somehow turn off. As Monday to Friday rolled along she felt more and more trapped. She had a nice boyfriend: Alan, tall, good-looking and someone you could take home to fish fingers for tea. It wasn’t hot passion. When Alan started talking marriage, the alarm bells went off. There had to be something more, hadn’t there? Brenda, her best pal, had found that working as an au pair in America. Or so she said in her many gossipy blue airmail letters about the boys and the wild nights out.

‘America? Never!’ screamed Grandma Dorothy. ‘What’s wrong with life here? It’s good enough for the rest of us.’

But it wasn’t for Mum. She felt she’d been nowhere, done nothing. And, strangely, she didn’t belong. She was searching for something that she, never mind her mum and dad, couldn’t understand. She dismissed her parents’ predictions that she’d be bored and homesick. But she respected them enough to compromise about going to America. She read an advertisement in the Lancashire Evening Post placed by an Italian company that employed English au pairs. The catch was she had to get to Italy to get the job. Her mum and dad reluctantly gave their blessing – Italy was better than flying across the Atlantic – and after eleven long weeks of Saturday night telly, spending nothing, going nowhere, she had the fare to Milan.

‘Our Gracie’, her Nan’s favourite old-time singer Gracie Fields, who’d been born over a fish ’n’ chip shop in Rochdale, Lancashire, now lived in Capri. That was Italian! It was all very well to go to America, she thought, but at least with Europe it would be easier to get back home if she hated it. She arrived at Milan’s Malpensa Airport with thirty pounds, not one word of Italian, and the astonishing high hopes and optimism of a twenty-one-year-old Lancashire lass.

She was a sensation. In 1967, blonde English girls were still something of a novelty. And she had an instant friend, Ada Omodie, who was eighteen years old and the eldest of the four children she’d been hired to look after. They were soon in a bartering relationship: Pat helped Ada with her English and Ada taught Pat Italian.

It was La Dolce Vita. Pat and Ada would go shopping together, and she went on holiday with the Omodie family to Rimini where they had their own villa. Guests included Giovanni ‘Gianni’ Rivera, a star of AC Milan and the Italian national soccer team. And Pat attracted as much attention as the celebrities at the swimming pool parties. It was something she was getting used to. The Omodie family lived in central Milan and there would be lots of wolf whistles as she walked the kids to school each day, even more when she wandered home on her own. She looked straight ahead, ignored everyone.

Except Alessandro.

He was the lot, the Trinity, tall, dark and handsome: he had an angelic face, like a Renaissance painting from her art books. Pat fell head over heels when she spotted him standing in the doorway of the barber’s shop where he worked. She saw him, and he watched her every school day. But they didn’t speak to each other until one day when Pat was struggling with some brown paper sacks of shopping and Alessandro offered to help her home.

The romance began, her first true love, her first lover. She spent every moment she could with Alessandro: he filled her days, her thoughts and her life. It was that unbearable first love, the one that catches your breath, that’s so intense, so overflowing with energy, it’s a surprise you don’t explode.

They talked in Italian all the time; Pat had learned her lessons. They spent days off and holidays travelling around to Rome, Naples, and most often to nearby Lake Como where they would picnic by the water and he would whisper her name and they’d make love.

When the Omodie family said they were leaving Milan she didn’t go with them but searched desperately for a job close to her man, near Alessandro’s barber’s. She rejected nanny and au pair positions all over the city until one location worked for her. The kids were a nightmare but that wasn’t going to ruin her dream. Alessandro, a young twenty-three years old, was going to do that all by himself.

They were on one of their regular Sunday afternoon trips out to the Lakes. Alessandro was quiet and thoughtful as he laid out their blankets. They’d been together for more than a year and Pat thought he might be going to propose to her.

Instead, she shivered in the sun as he said: ‘Patti, I love you, but I can’t ever marry you. My family have arranged for me to marry someone else. I have no choice, no choice at all.’

Pat couldn’t believe it. It was absurd. Alessandro was from southern Italy, where the culture could be as strict as Islam, but an arranged marriage? In April 1969? She couldn’t, couldn’t understand.

Alessandro tried to explain how serious it was. His parents had discovered he was seeing an English girl. His father was so indignant he took a knife to his son’s throat and hissed, ‘You stay with this English girl over my dead body.’

Alessandro said they had to end their affair then and there. It was over, for ever.

‘I’m so sorry, Patti, but there is no other way. I have no control over it. I have to do what my father is asking me.’

She begged him to change his mind. He could run back to England with her. They could hide in Italy. Go to France. America. It did no good. They were both crying as Alessandro drove them back to Milan. He gave her one final kiss when he dropped her off. It felt cold.

Pat sobbed and sobbed for weeks. She only slept when she was utterly worn out with exhaustion because her mind was spinning, asking questions around the clock. It was really just one question: why?

The only thing keeping her sane was the hope that it was all a mistake: Alessandro would come back to her, the arranged wedding would be abandoned and all would be well.

That was a fantasy; the reality meant more heartache. Friends told her Alessandro had met his future wife and the wedding date had been set. She snapped. The crying stopped. With no more tears left in her, she went to see Alessandro at his barber’s shop. Hysterical, she screamed for her lover to come out.

‘You’ll get me killed, Patti!’ Alessandro shouted back. ‘You’ll get me killed if you do this! Go away before someone sees us.’

He slammed the door in Pat’s face. With a loud crack he threw back the heavy bolt. It went into her heart.

She found the tears again. They flooded out as she limped off down the street. She was sobbing so much she could hardly see the two young guys asking if she was OK, if she wanted a lift home.

Love had turned into frustrated anger and Alessandro, the man she wanted so terribly, was the only one she could take it out on; cursing him, she was thinking in a mixture of English and Italian: ‘Right! I’ll show him what’s what. Vivi il presente.’

Without a thought about what she was doing, she got into the back of what she soon realised was a very smart car. It seemed brand new. She could smell the leather.

The driver, who introduced himself as Luca, said: ‘Momento!’ They had to wait for another friend, just a couple of minutes and they would be on their way. They would look after her, take her home. She mustn’t worry, must stop crying. The other guy, Franco, got in the back of the car with her.

Pat didn’t care as the moments ticked on. She sat silently all wrapped up in her aching upset. It was the end of her world, of her life. She was traumatised. She felt dead inside.

Suddenly, the driver was talking to someone. There was a clunk and a pull at the front passenger door. A short, wiry young man with a flowing flop of black hair climbed in beside the driver.

He twisted, whirled around, and stared at Pat with a naughty grin: ‘Ciao, bella! Ciao, tesora.’ [‘Hi, lovely! Hi, beautiful!]

His name was Emilio. Emilio Di Giovine.

CHAPTER TWO WONDERLAND (#ulink_d5a4026f-3bc7-5d24-8a3a-e0c84507d21f)

‘To be honest, as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.’

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE,

HAMLET

Luca, the driver, invited Pat to a nightclub and she agreed. She wanted to forget Alessandro. She put on a yellow dress to brighten her spirits and went out intending to have some harmless fun.

That evening Luca’s best pal Emilio Di Giovine once again magically materialised in his tight shirt and tighter pants. He arrived late at the noisy, smoke-filled nightclub, explaining that he’d crashed a borrowed car and the owner was not amused. Emilio was not bothered. As his friends jabbered questions about the accident, he shrugged: ‘It happens.’

His eyes were watching Pat dancing and he was soon making his way across the crowded dance floor to talk to her. It was as if Luca didn’t exist.

‘Do you want me to take you home? Why don’t you go out with me?’ He said he would take her out the following night.

‘You’d better not take me home,’ she said. ‘I came here with Luca.’

But Emilio came round the next night and the two of them went to a funfair. From then on, he kept coming to pick her up, each time driving a different car. They were all spanking new and when she queried this he told her: ‘My dad has a garage.’

After stealing a kiss on an early date he said, ‘Pat, you’re the kind of girl I want to marry.’

Mum was twenty-three years old and she’d heard plenty of chat-up lines so she laughingly brushed this off as nonsense. It was silly, Italian Romeo talk from a boy who was only nineteen years old. Her instinct was to tell him to hop it. Yet it was nice to hear the passionate patter after the heartbreak of Alessandro. It was good for her self-esteem to feel wanted.

And so was his lifestyle. She couldn’t get her head round the new cars: a Porsche on Tuesday, a Mercedes on Thursday and a nippy Alfa Romeo for Saturday and Sunday. There was always something new for the weekend.

‘Emilio, what do you do?’

With a charismatic smile and not a hint of shame, he replied, ‘I race cars and work as a mechanic at my father’s garage.’

As far as Pat was concerned, he might have said he was going to the Moon along with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin who’d just become the first men to take a stroll up there. It didn’t make sense to her. It was curiouser and curiouser. Their trips around town only confused her more. The flash cars weren’t the attraction. He was like a magnet for people, who hurried over to talk to him as if they just wanted to be seen near him.

Everywhere he went his language was cash but in many bars and restaurants his money was foreign to them; the owners wouldn’t take it, saying their meals and drinks were on the house. He wore bespoke suits, his shirts and ties from the Via Montenapoleone designer shops, his shoes imported, English and cap-toed. He was groomed to perfection, having a wet shave and his moustache trimmed every day at the barber’s. There, his double espresso and his toasted cheese panini were always waiting as he took the central chair, like a celebrity. It was fascinating. She seemed to have stepped into some extraordinary wonderland.

And Emilio was a get-things-done kind of guy. Certainly, when Pat had problems with the family she was working for he was quick to sort things out.

One night after she put the kids to bed, the father tried to get it on with her. Pat realised he was horribly drunk and told him to get lost. She went off to bed in the room where she slept next to his daughter. She woke up with the guy trying to feel her up under the duvet and that was that. She ran out of the house and called Emilio.

‘Pack your stuff,’ he told her. ‘You’re not staying there. What’s he going to do next?’

She went back to get her things but the family wouldn’t open the door to her. When Emilio arrived Pat was a wreck, sobbing outside the apartment building. He took one look and told her to wait in his car. She tried to say he shouldn’t do anything but he took off in a rush of virility.

Within minutes he’d returned with her bags all neatly packed. He’d ‘sorted’ the problem. The sex pest would never bother her again. She never found out what he had said – or done. Emilio had no difficulty finding a girlfriend who would let Pat stay until she found another job. By then they had become very much a couple and Pat found out she was pregnant with me.

They’d been lovers for just sixteen days.

Emilio was delighted and his parents were even more so at the prospect of their first grandchild. Emilio was the adored eldest son and Nan opened the doors of her home to him and Pat.

At that time, Nan’s had two bedrooms, a huge front room, kitchen and bathroom, and eleven kids, aged from nineteen downwards, with Auntie Angela only a few weeks more than a twinkle in Grandpa’s eye. Mum and Dad were given their own bedroom. Nan and Grandpa had the other. The rest had to lump it where they could. It was pandemonium. There were kids everywhere, crying, shouting, screaming, laughing, and they all seemed to be fighting. It was like a coven of hysterical little demons.

‘They’re all mad here,’ thought Pat with a grim grin to herself.

It was all falling into place, as if her destiny was mapped out for her. She had no choice. She wasn’t really in love with Emilio. She was still in love with Alessandro and Emilio was her boyfriend on the rebound. He helped her.

When she was a few weeks’ pregnant she went to Blackpool and told her parents, who were distraught. Where was the man who’d got their girl pregnant? Where was this Emilio? They were horrified, in their quiet, behind-the-curtains English way, at how things had turned out. They had hoped Pat would return quickly after her Italian adventure but she had arrived home to announce she was pregnant and was going back for good to raise their first grandchild. Their big, repeated question was: ‘Who is this Emilio?’

Pat didn’t tell them because she still wasn’t sure herself. Instead she offered: ‘He’s a good man. He’s looking after me. I’m happy.’

And deep down Pat really hoped she would be.

When she returned to Piazza Prealpi, she started getting affectionate with his parents, with all the brothers and sisters, learning much if not all about the family’s history. Her emotions were all over the place, but she wanted to belong, to make it work with the young Emilio and the baby that was on the way. She’d never met a man quite like him before.

‘Better,’ he’d always say, ‘to live like a lion for one day than live like a sheep for one hundred years.’

Yet even in the Mafia, there were questions of propriety. Nan put pressure on Emilio to ‘do the right thing’.

Only eighteen days after I was born, on 9 March 1970, they became man and wife at a registry office close to Piazza Prealpi, with Emilio in a dark suit and Pat in an understated brown dress she’d bought at C&A in Blackpool. Grandpa Rosario, who was a witness, looked as if he was at a funeral. Pat’s parents weren’t there. The wedding reception was pasta at Nan’s.

There, Pat overheard her husband and father-in-law talking in the kitchen.

‘Emilio, I’m worried about this girl. She’s going to ask too many questions. She’s English – she won’t understand how things work. She could really fuck things up for us.’

Grandpa was told there was no problem. No one was going to stand in the family’s way, certainly not Pat. It was business as usual.

As if to prove it, Emilio celebrated his wedding night by going out drinking and gambling with his smuggling crews. His bride spent the night alone, looking after the new baby – me – and worrying about our future.

Emilio was nimble-witted, nerveless and remarkably fluent in violence and villainy. He was an heir to that audacity. Just like his mother.

Nan was born on 14 November 1931 in San Sperato, right by the tip of Calabria, on the Strait of Messina across from Mount Etna in Sicily, as deep in the wilds as you can go. Her family were partisans in the mountains during the Second World War, and ‘partisan’ in their world meant they were fighting for each other, for themselves.

They were infamous. They fought fiercely against the Germans, against Mussolini. They were against anybody and everybody. They quite liked the American soldiers for the black market in chocolate. In their own interests, they dealt in protection, extortion and contraband. It was more ruthless than sophisticated.

They were traditionalists, keeping the faiths of the ’Ndrangheta, whose bad business goes back to Italian unification in 1861. The ’Ndrangheta didn’t need secret codes because the Calabrian dialect is impenetrable. In the early days the poor but proud and angry Calabrians banded together against the rich squires who’d taken over what they saw as their land. There were about 400 people in San Sperato and most families managed to grab a chunk of land.

It hadn’t changed much when Nan was growing up with eleven brothers and sisters, a family bred to war in the Calabrian hills. All of them were crushed into a half-built two-bedroom stone house. The Serraino family, like the others, grew olives and lemons, but they also dealt in contraband cigarettes and liquor, mostly cognac stolen from Calabria’s huge Gioia Tauro port – Italy’s ‘passport to the world’ – which was under ’Ndrangheta control. In the shade of melon stalls on the dirt roads all around the countryside, the illicit booze and tobacco were bought and sold. The police collected their payoffs in kind, bottles of brandy and wine, a couple of cartons of smokes, towards the end of Friday afternoons.

‘Have a nice weekend,’ they were told.

It was the family legacy, the family economics, venal but effective: control the trade, supply the demand, and fear no one. Indeed, keep the authorities close to you, pay them off, corrupt or kill them. The Mafia code: keep your friends close, your enemies closer. Perfection would be everybody on the payroll.

It didn’t always work. Some of the police, not many, were straight, or under some sort of regional government control and obliged to make the occasional arrest. That meant that many of those around San Sperato – for everyone had some connection with the ‘black’ economy – spent at least a short time in jail.

That included my great-grandfather Domenico ‘Mico’ Serraino, who was given six months in Calabria Prison for a robbery in the summer of 1947. They didn’t take into consideration any of his other fifty or so offences – that year – as somehow they were never registered in the paperwork.

Domenico Serraino was known as ‘The Fox’, and was cunning in the extreme. His wife, my great-grandma Margherita Medora, was from a similar family. They were peasants who hadn’t had any schooling. He lived in a narrow world: sons of sons were on pedestals, sons of daughters were undeserving of his attention. The sons of sons were gods but grandchildren with a different surname were not allowed to eat with him. If they came close he would chase them away with the back of his hand. Nan was a blessed Serraino.

It was her job to visit her father Mico in prison, to take provisions, cigarettes and wine. The prison guards would receive their ‘allowance’ during the visit. She was very much a sweet sixteen-year-old in appearance but already wily in the way of a born Calabrian, truly The Fox’s daughter. That gave her the confidence to take a chance on romance with the fresh-faced twenty-year-old prison guard who chatted her up during her visits. There was a real sparkle between them. Rosario Di Giovine was new to the prison, new to the area, but linked by bloodline to the South. His dad worked in Rome in the prison service. It was just after the war and work was hard to find so his dad got him this state job. It most certainly wasn’t a vocation.

Still, he didn’t realise that getting involved with Maria Serraino could get him killed. Just for spinning her a line.

There was no way Nan could take a prison guard home to meet the family. It would be like bringing home the cops. She’d have been disowned and Grandpa would certainly have fallen off a cliff.

Nan found a way. She offered to do the washing for the prison guards in return for a little money. It was an excuse to keep visiting the prison after her father was freed. And Rosario Di Giovine was a quick learner in the ways of Calabria. They kept their affair secret and later my grandpa quietly left the prison service and avoided the caf?s and bars the other officers went to. His time there didn’t even stay on his CV. It was as if it had never been. Instead, he became a truck driver, a very useful skill in the Serraino family.

Rosario had a way with him but his charm was tested as Nan’s father and brothers watched closely. In those days you weren’t ever left alone with a man. You had to have an escort. If you went out for an ice cream you had to have a chaperone. That’s how it worked. And it worked double for newcomers like Grandpa. He could feel the eyes on him. But true love always…

As a young couple time dragged for them, so before long they’d run off together to another village in the mountains. The family realised what had been going on and, sure enough, Nan was pregnant.

The atmosphere was difficult, with tension and violent arguments between Grandpa and Nan’s brothers, but circumstances dominated everything. They married and my dad, Emilio, was born twenty days before Christmas in 1949. The Serraino–Di Giovine dynasty had begun and so had the baby production line. While Grandpa became a trusted lieutenant and started driving contraband for the family, Nan began giving birth.

In those tough post-war years, even with all the ducking and diving, the thieving and smuggling, it was an almighty struggle to stay ahead. The ways of Calabria were always respected. My nan was the one who kept everything together and she was always taking in strays, both kids and dogs. She was a lovely, genuinely giving woman, but she had a ruthless streak in her. If you did something bad to her family or disrespected them, she wouldn’t think twice about getting you beaten to a pulp. Just like that she would kick off. That was the world she had always lived in.

When her son Emilio was four years old his grandfather made him watch a pig being slaughtered. The pig’s throat was slit in front of him and the blood dripped into a bucket. This little boy had to immerse his arm up to the elbow in the blood and stir it so it wouldn’t coagulate. There wasn’t room for waste because they wanted to make a batch of blood sausage. Emilio had to keep stirring the blood. That was the side of the family that made him a man. That’s how all the children, the masculine children, as they put it, were brought up.

Kindness to strays and buckets of blood? One extreme to the other.

By 1963, Emilio had six brothers and four sisters and they were all living like chickens, constantly scratching for space and food. It was then Nan decided life would be better in Milan. It was like moving abroad, going to Australia. It was faraway and foreign to them. But Nan packed her bags and her kids and moved north. She had some money saved, and she had guile and single-minded determination. It was enough to get them an apartment on the Piazza Prealpi, which is where La Signora launched her criminal organisation (which was worthy of that title from the start).

She made associations within the Milanese underworld but most important was the established Calabrian connection: from there, at first, came the cigarettes and booze, the currency of her start-up operation. Her gang were a young, wild bunch. Over time all her kids were in the act: Emilio and his tough-guy brothers Domenico, Antonio, Franco, Alessandro, Filippo and Guglielmo. And his sisters, Rita, Mariella, Domenica and Natalina had walk-on parts too. And the ‘strays’ were thankful to help by running errands.

Nan was ever-purposeful; nothing was done by chance. She spoke with a distinct and difficult dialect. It’s very hard to understand – she really needs subtitles – unless you’ve grown up with it. However, her meaning was always crystal clear.

The Piazza Prealpi, fifteen minutes from central Milan on a slow traffic day, was pivotal to her empire. The square housed an assortment of market stalls with flapping awnings and flaking paint where you could buy the fresh basics for breakfast, lunch and dinner. On other smaller but busier open-air stalls there were younger, louder guys selling newspapers, magazines, booze and cigarettes. It was a downbeat neighbourhood of city life and lives. But families didn’t have to go any further for their needs. The caf?s, bars and restaurants were open from dawn until the small hours. There were always people about, happier to sit outside than in the squashed, dull blocks of council flats which comprise the Piazza. There was an eager, waiting market for anyone with commercial enterprise, a bit of get up and go.

Nan instantly realised the potential to sell cheap cigarettes and hooky alcohol in the square and make a fortune. She knew that contraband bought in volume and without duty could be sourced and sold much cheaper than it was at present, but still at immense profit.

She didn’t rush at it. She began slowly by selling to the shopkeepers at knockdown prices which became lower and lower, so low that people came from all over the city to buy. She met the demand.

Nan held ‘board’ meetings every morning in her kitchen. Once her children reached a useful age they were told what to steal, how to steal it and who to move it to. Go here. Get this. Do that. Speak to him. Come back to me. If one child ratted on another, told their mother that one of the others had stolen something, the telltale was beaten. Mercilessly. The rule was you said nothing, you kept quiet or the punishment was harsh. The code of silence, omert?, trumped blood bonds. Nan’s law was: ‘You have to shut up.’

Emilio and the others never went to school. Nan was the headmistress, discipline was the whack of a big, stained wooden soup spoon. There was one supreme teaching: ‘First make them fear you. Then they will respect you.’

Nan had few dreads. Maybe God, the Catholic church. I would watch her in the afternoons when she stepped outside the apartment and put her chair out on the street. She would sit there quietly holding her rosary beads and I’d get goose bumps hearing her prayer: ‘God, forgive me for anything I’ve done today.’

Yet, the legend was she knew things before God did. She had eyes in the back of God’s head. She certainly paid him off. The Church was the only place her money went, other than the family and professional expenses. She gave thousands to the Church, perhaps to assuage her guilt. Maybe it was bribery of the Almighty – paying for a place in Heaven? She used to send fabulous clothes (stolen, of course) inside the prisons. She gave thieves heroin: it was a vicious circle. She donated all kinds of goodies to the nuns and priests who worked with the poor in Milan. No one ever asked where they came from, which was just as well. I think it made her feel a bit better inside, that she was balancing things out. None of the family went to confession because everybody thought the priest would have to be paid off to keep his mouth shut. I’m not sure if Nan was bartering with God but she certainly did that with every living thing.

Elsewhere it was cut-throat business. She abruptly axed the legitimate suppliers who had been dealing to the Piazza Prealpi stallholders for decades. It was simple business from both sides of the market stalls. Nan could sell everything cheaper and eventually almost all the shopkeepers and landlords in the Piazza took daily deliveries of knockdown stock.

Supposedly, Grandpa Rosario worked as a regular truck driver. It was a pretty transparent ‘cover’ to prove the family had legitimate income. All that was regular were his trips – over the border to Switzerland where cut-price cigarettes were available.

He and Emilio ran the smuggling syndicate. Emilio was only fifteen years old when he began running a team of two dozen teenage drivers to and from Switzerland with secret compartments under the back seats of their Fiat 500s jammed with contraband cartons. In this way, more than ten thousand packs of cigarettes a day were delivered to Nan’s. When they arrived, crow bars were used to wrench forward the back seats to reveal where the cartons were concealed.

The other legitimate suppliers were severely pissed off. They complained to the police. Uniformed officers felt obliged to investigate and they became regular visitors, always leaving with one or two twenty-pack boxes of Marlboros and a kiss on each cheek from Nan. As word got around the precincts the police faces changed and the gifts became more lavish: expensive jewellery, champagne, a stereo system. She could afford the tempting payoffs.

Nan’s ability to obtain cheap cigarettes and move them on without fuss or interference from the police earned her a reputation across Milan. Soon she became a major fence dealing in all manner of stolen merchandise, whether it was a car radio or a gold Rolex, a cashmere sweater or a used video. If anybody nicked anything anywhere it would go to my Nan’s first. She had first refusal. When someone brought a stolen goat she didn’t blink; she tethered it, fattened it and sold it ten days later. There was nothing Nan wouldn’t buy and nothing she couldn’t sell on at a profit.

And she wanted no competition. If any opposition tried to move in, she dealt with it the Calabrian way. She eradicated the problem. She carved out, literally in some cases, a fearsome reputation. With the police in their pocket it was made very obvious the Di Giovines were the kingpins. The family was devious in many things.Nan hadn’t been educated and couldn’t read or write but she could count money. Very well and very quickly. Nan was the Godmother. People would come to her with their problems and she would help. It established loyalty and connections.

She ran her organisation with military precision and controlled it by military methods. The rules and the consequences for breaking or challenging them were severe. If someone had to be punished Emilio would be instructed, given the assignment. If he was pulling the trigger to whack someone on the street at 11 p.m., it was Nan who had told him where to aim the gun five minutes earlier.

And there was always a beef to sort out. If a rival came into the Piazza trying to deal stolen goods or sell smuggled cigarettes, Emilio would go to sort it. The square belonged to the Di Giovines and my nan’s view was that the bastards had to know who was the boss. Emilio was the Enforcer, dealing out beatings, kicking people to the brink of death. He was short, only 5 foot 4 inches tall, because he’d had a milk allergy as a baby. They fed him tomatoes instead, and the doctors said the lack of calcium stunted his growth. But despite his short stature, no one doubted how deadly he was. He had a reputation for being big down there, well proportioned. His family nickname was Canna Lunga, the long cane. His brothers used to joke about it. He was very good-looking, very charismatic. He just had a way.

When he was younger Emilio wore insteps in his shoes to make him taller. But it was confidence that gave him his swagger on the streets; a brash Napoleon, he did not fear anyone. Idiots would always get one warning to clear out the area but the second time they would get hit.

‘Fuck up a third time and I’ll kill you.’ He meant it.

He got results and his fearless determination to protect and control the area for the family attracted businessmen, shopkeepers and families with their own difficulties. They would go to Nan’s, leave cash and wait for Emilio to solve their problems. With that, the family had one of the most profitable protection rackets in Milan. And if protection duties were slow there was also the flip side, extortion.

‘Maria, these guys keep coming in and stealing stuff off my shelves.’

‘La Signora, some fellas smashed up my bar on Sunday night.’

‘Maria, this guy two blocks down is setting his prices so low I am going to go bust and I can’t buy from you any more.’

‘Send for Emilio’ was the chorus, the solution; going to see Nan meant things were dealt with more efficiently and far quicker than if they went to the police – who Nan was paying to keep their noses out anyway. She had all the ends covered in her kingdom. For Nan this was a gold mine.

However, it meant that my kindergarten was an armed compound and my criminal career began when I was a few months old. That’s when I went on my first smuggling mission. The police have the photographs to prove it.

CHAPTER THREE MARLBORO WOMAN (#ulink_526b3b82-091c-5b5f-af6b-520626debcc5)

‘I said blow the bloody doors off!’

MICHAEL CAINE AS CHARLIE CROKER,

THE ITALIAN JOB, 1969

When my mum first moved into the Piazza Prealpi apartment it had been customised for crime. Nan was an exceptionable presence in Milan and despite the payoffs police raids were always a threat. There were compartments, nothing more than holes in the wall riddled around behind the kitchen skirting boards, where Nan kept handguns. There were other hiding places – beneath radiators, in cisterns, at the neighbours’ – for more guns and cash. Many of them were places where only a small child’s arm could reach. She was a female Fagin, my nan.

And her den, the apartment, was a constant bustle. Everyone was asking for more – more tobacco, more bottles of booze, more anything-off-the-back-of-a-lorry, and, always, always, more money.

Mum was dazed by the chaotic and crazed lifestyle; there were usually so many people sleeping over she couldn’t count the number. Names? She was still keeping up with the names of Dad’s brothers and sisters. So from dawn till midnight she just nodded hello when the scores of strangers marched into the apartment carrying boxes. Mum had an idea of what was going on around her but never imagined the scale of it; any questions never quite got an answer. She didn’t push my grandparents; she was grateful for all they were doing for her and for me.

In return for the generosity, Mum helped run the household, working with Nan and Dad’s sisters cleaning, washing, ironing and preparing food. There was always someone around to watch me, play with me. I had all the love and attention in the world.

Mum learned to bake bread, make pasta and create authentic Italian meals, mostly using recipes by Ada Boni, the famous 1950s Italian cookery author. She favoured feed-everybody dishes like Chicken Tetrazzini, a casserole with chicken and spaghetti in a creamy cheese sauce. Nan would be up at six in the morning cooking. In between doing her deals, she was at the stove. We’d wake up to the smell of food. It wouldn’t just be sauces; she would cook all sorts of dishes, including veal, chicken, fish, even tripe. She had a freezer full of meat, polythene bags stuffed with cash hidden among the ice cubes, and boxes and boxes of nicked gear in her larders. She was a regular Delia Smith, but with a .38 revolver in the spice cupboard and a couple of other handguns in the dried pasta. Instead of shopping lists, she would have notebook catalogues of dubious contacts for every possible chore, surrounded by cans of chopped tomatoes. Cooking was her therapy. She never went out. She never did anything. She didn’t smoke, she didn’t drink. Her interests were totally family and business, the Calabrian way. And I adored her. She always had time for me no matter what dramas were going on – and being an Italian household everybody knew about them. You heard them! Very loudly. But even the noise was a comfort to me. It meant that the family were all around and I was safe. It was my warm blanket.

Nan would cook lunch for whoever was there and Mum would be in charge of supper, when there were always at least twenty to feed. Mum felt she was beginning to belong. Her spoken Italian was good but bastardised, using the family dialect, a magicking of Calabrian and Sicilian; she so enchanted the market stallholders when she was out shopping that they called her ‘the blonde Sicilian’.

But she was aware she wasn’t having the same effect on Dad. She’d prayed she would feel the same heart-stopping emotions she had felt for Alessandro. That it would work out between her and Dad. That he would grow out of being a jack-the-lad driven by his lust for new excitement, for girls and fast cars. What she didn’t and couldn’t fully understand at first is what it truly meant to have the blood of the Serraino–Di Giovine family surging through him.

Her education didn’t take too long. There was little to do most evenings, after the cooking and the washing up, but talk. And, more importantly, listen. She never heard the words Mafia or ’Ndrangheta for they were never spoken. She realised there was a lot of ducking and diving going on, but if Emilio was making money dealing in dodgy cigarettes it didn’t seem too serious to her. On the crime scale she thought it was a bit like bringing in too much duty free. Certainly, that’s how the family’s ever-growing mass smuggling operation was presented to her. And Mum heard what she wanted to hear. She was wise to do that for she was about to be recruited by the ’Ndrangheta.

Dad’s smuggling crews criss-crossing in and out of Switzerland at the Italian border town of Lago di Lugano were being increasingly hassled at the checkpoints. He decided to ‘disguise’ the trips as sightseeing and romantic days out and sent drivers across accompanied by women. Dad began taking Mum on his own runs. It worked: the police pressure eased, and the volume of cigarettes being brought back to Nan’s doubled within a few weeks.

Dad tried not to let Mum in on the extent of the family operations. It was a feeble effort. She saw him carrying a gun. She saw the police arrive threateningly and leave happy. If she did question any of the bewildering events the answer was always: ‘There’s no need to worry or get involved, so don’t.’

Her big question – to herself – was when our family was going to get its own home. So, in her protective way, she was just happy Emilio was out earning some money, which she hoped would bankroll an escape from the shoebox life at Nan’s. That we would be a family unit, not part of a daily and increasingly crazy cavalcade at Nan’s. She wanted to raise me in Italy where she had made friends.

Vital to that dream of domestic bliss was her relationship with Dad. She couldn’t ignore her inner self which told her she didn’t truly love him; they were brought together by circumstances. Yet falling pregnant was a big deal and, rebound guy or no rebound guy, the rules were you stayed together and tried to make it work. Well, that was how she saw it.

After the long kitchen table drama when I was born and she held me in her arms, her emotions, her heart and mothering instincts, took over. Her life purpose was now to care for me and she didn’t want to do it as a single mum. She wanted me to have a mum and dad.

For Dad, his only concern then was business, which was booming and expanding into even more dangerous territory. The Turkish gangs running drugs throughout Milan were hiring ‘money collectors’, teams of hard men to bring in the payments. Dad started making tidy sums from this but saw the dealers themselves getting lavish payoffs of more than ?10,000 a time, which was enticing. He was still indulging in his favourite pastimes, stealing cars and dating girls. When the girls met him he always had a polished Porsche, a red Ferrari – he likes red – or a new Alfa Romeo. A racing driver? It didn’t look or sound to the girls like the buckets of bullshit it really was.

Mum was just keeping her head above it all. Dad was gone a lot of the time and she was pretty sure he was having affairs but she couldn’t prove it. She was lucky to be single-minded and determined, for the toll on her was incessant; flirting with postnatal depression and not knowing what shocks or surprises would present themselves each day – and there were usually one or two – she remained strong.

Mum desperately wanted her own space, and Dad finally got us out of Nan’s and into a small rented apartment. It wasn’t grand but it was our home and an escape from the bedlam of Nan’s house, where there was another baby, Auntie Angela, who was only a month older than me, and the raging testosterone in the house with all my uncles. They were growing up, doing their own thing, having their own bit of business here and there. There was fighting between them but nobody would dare fight with them. It was ‘I hate you, but nobody else can hate you.’ If any harm came to one of them, then everybody would band together. It was like a circus with lots of zany characters and hoops being jumped through. Nan was the ringmaster in a sauce-stained apron. Some people would shrink back when she shouted but I knew she only raised her voice to those she loved. If she shouted at you, everything was OK. Silence wasn’t golden, not at all.

I was now very much part of it, by blood, and that’s a lifetime bond. And because of me, so was Mum. But for much of the time it was the life of a single mum. She didn’t know what Dad was doing, where he was going or who he was seeing from one day to the next. He was all over the place with his smugglers. The consignments grew and grew. But the bigger they were, the bigger the problem of moving them into the country.

Mum had been to England to show me off to her parents and returned with a present, an elaborate carrycot with lots of side pockets for nappies and all the other baby paraphernalia. When Dad examined it, he noticed there was also a slot underneath where he could hide dozens of cartons of cigarettes. Instead of a traditional family lunch, he began taking us out in the grey Fiat 500 for a 45-minute drive to Lake Como, where we would collect the cigarettes and then return for tea with some of the contraband concealed in the car and me lying in my cot on the rest of it. Dad was so pleased with this scheme, he took photographs of me lying on a Marlboro mattress. There’s one picture where I have a cigarette on my lips, the Marlboro baby. Little did he know that the police would come upon these pictures one day in the future.

Mum and Dad’s life appeared to settle, but there’s no smoke without fire. He was still vanishing without warning and leaving no message telling where he was. Business. Always business. But he was around enough for Mum to get pregnant again. An accident. And a tragic one in so many ways.

Dad continued fooling around. He was still only twenty-one years old when he got involved with a blonde English dancer called Melanie Taylor, who was touring with a cabaret show. She thought she was in love with him. She was only one of the girls he’d been seeing but it had been going on for some time. Mum, heavily pregnant, heard his brothers talking about the relationship. Finally, she lost it. She marched off to the bar where the dancing girls went in the evening. She burst in, telling them to let this slag Melanie know that the guy she was screwing was her husband and she was expecting another baby with him.

When word got back to Dad about what had happened, he calmly walked into the bar and told Melanie and her friends that Mum was mad. He was cold and calculating and claimed she was pregnant by someone else and he was leaving her over it. Everyone believed what they wanted to believe.

Mum had vented much of the rage from her system, and she was mentally and physically tired and weary of it all, so she got on with having her second baby. She knew it was going to be another little girl. Dad didn’t bother to turn up for the birth, which this time, at Mum’s insistence, was at the local hospital. My sister Rosella was born but it was two days later before Dad visited and even then he turned up with another woman.

Nan saw red at this and dragged the girl, who didn’t know any better, out of the car and battered her, shouting: ‘You ugly whore!’ She loved my dad, but she didn’t like what he was doing, so she took it out on the nearest person who wasn’t family.

When Dad got to the bedside my mum said: ‘You’ve just been with other women, haven’t you?’

‘I swear on this baby’s life I haven’t.’

It was terrible, tragic. Tiny Rosella died three weeks later. She’d had lots of health complications but officially her death was down to tetanus.

Mum was devastated. She felt lost, and she knew that was definitely it with my dad. It was over. I was a little more than a year old. Mum had one baby and no income. She couldn’t afford to keep paying the rent at the apartment, so she had nowhere to stay.

She went ‘home’ – in other words, she went to Nan’s. That’s all that made sense to her. Nan was on Mum’s side. Family.

And, of course, business. Nan paid for Mum to have driving lessons. When she had her licence – Nan didn’t want any traffic laws being broken – she started in the cold mists of winter doing solo cigarette runs. She’d drive to Lake Como and also into Switzerland when cheaper consignments were on offer. Sometimes one of my uncles would go along.

It was her way of displaying loyalty to the family and earning some money for them. All the time I was happily being looked after by Nan and her troops of helpers. Dad? He was going up in the underworld, his enterprises far more dangerous and lucrative than before. His lifestyle reflected that.

For Mum it was make do as she could. She wanted us to get our own place away from the crowded craziness of Nan’s and put us down for council accommodation. It didn’t take long. I was nearly three years old when we moved into Quarto Oggiaro, into the ‘Mussolini flats’, the largest social housing district of Milan. The concrete camp of a neighbourhood started by the Italian dictator was home to immigrants, first from southern Italy and, when we moved in, from Turkey and Yugoslavia, making it a colourful melting pot.

For Mum it was our first home together and special to her. But not to anyone else. It’s the roughest place in Milan, and Milan’s a big city; a poor, grey downtrodden estate for thousands of poor people, chilled in the city fogs of winter, oppressive in the summer heat.

We had a big room, twenty by twenty, that we slept in, ate in, did everything in. It was token rent, the equivalent of a couple of pounds a week. We didn’t get much for that: one bed for the two of us, a small kitchen corridor and a little toilet. We didn’t have a bath or a shower. We’d go to Nan’s house to have a really decent wash. If not, we used to have to go to the public showers. I’d grip Mum’s hand as we stood in line to take our turn under the water. It didn’t matter what time or what day we were there, the water was always freezing cold: almost refreshing in the summer but cruel in winter.

It was about a fifteen-minute ride on the number 7 or number 12 tram and then a ten-minute walk from the Quarto Oggiaro over to Nan’s where I still saw my dad. He was always smiling when he saw me and I loved it. I wanted to hug him for ever. Yet, in a little kid way, I couldn’t understand why I didn’t see him every day. Didn’t he love me as much as I loved him?

He wouldn’t be seen dead at our place, the poorest area in the city. He drove a chocolate-coloured Porsche – this one was paid for – and lived in a really exclusive area. ‘Why are we like this, and my dad has got all that?’ I wondered.

He took me to meet Daniella, one of his girlfriends, who had a son about my age. We went to a toyshop and he told us to choose something. I was used to having the cheapest things and picked a little dressing table with make-up and hairbrushes. The lad picked a powered pedal car that you sat in – it would have cost a fortune. I liked my dressing table but later the family teased me that the lad’s present was much better than mine and I got fed up with my dad about that.

Mum was the star. She worked all hours at the Upim market, which sold everything, a sort of mini Tesco. She did shifts to work around my school timetable.

I didn’t speak English, only Italian. I understood ‘sit down’ and ‘thank you’ but Mum only spoke Italian to me. She wanted me to belong. We had picture books, Pinocchio, Alice in Wonderland and other kids’ stories. The teachers made you eat courgettes and go to sleep in the afternoon and I hated all of that. They’d prop up cot beds and we had to lie there for about forty-five minutes and have a little sleep. I pretended I was asleep because you’d get told off if you moved or said a word.

We had white overalls and each class had its own different-coloured little collar – mine was red and orange. The overalls would be various shades and sizes, some better, some worse, depending on where you bought them, but you had to have them on top of your normal clothes. It was like any school uniform, an attempt to stop there being any ‘them’ and ‘us’ in the class or playground. Most of the kids were deprived anyway for it was that sort of neighbourhood, and on the stifling hot days of summer that left you breathless it could smell like a bad Spanish holiday.

For Carnival Day on 17 February I always had to borrow an outfit from Auntie Angela. She got the costume and I had to borrow it. Whatever she had, I wouldn’t get a choice. I was a fairy one time when I was very little. One year I got a Spanish flamenco costume that Angela had never worn and I was very happy; that was special.

The school was a five-minute walk from home and Mum would drop me off just before 8 a.m. when lessons and her Upim shift began. It was all co-ordinated. I finished school at 1.30 p.m., just as Mum’s first shift ended, so she picked me up and we’d go to Nan’s, then she went back to work until 7 p.m. Nobody from school ever came back to my nan’s. Mum kept that part of our life separate. Classmates would visit at Mum’s. Her friend Linda’s daughter Simona was in my class and her son Luca was a little younger. I played ball and rode my bike with them and a lot of other kids in the yard at the Mussolini flats.

I also caught nits, one of the neighbourhood hazards. I heard Mum saying, ‘Marisa, you’re not going to like this but I’ve no choice,’ and the next thing huge clumps of hair, my long, curly ringlets, were falling to the ground. When I looked in the mirror a little boy was staring back at me. I stood there screaming with tears rolling down my face. I was wearing red wellies, a red top and jeans and a shaven head. Mum took one of her ‘arty’ photographs.

That was a big drama for me. As a youngster I was protected from all the other dramas that were going on around me. Nan’s was always warm and comfortable when I stayed there in the afternoons and early evenings. There were more people and more room than at our place, and I loved my nan’s food. Meals seemed to last for hours. I had my cousins to play with and the family would never, ever leave us out in any way. It was ‘my house is your house’. When I went there it felt like my home. As soon as Mum and I walked through the door Nan stopped whatever she was doing and walked across the room and scooped me up in her huge arms. As she wrapped me up, pulled me close and kissed me on the end of my nose, I felt as though no one could hurt me. In her arms I would never come to any harm. She was always very giving and cuddly. I thought it was an amazing place. I’d never seen so many people in one house at the same time. It was full of excitement and love.

After meals I’d play with my skipping rope in the yard along with Auntie Angela, until it was too dark to see and we had to come inside. Then we’d chase the family dog, an Alsatian called Yago, all around the house until his barking became so loud that Grandpa would tell us to quit winding him up.

Everyone loved that animal but Grandpa. He hated it. One week when he had to travel to Calabria on family business he packed up his truck and hid Yago in the back. When he reached Calabria he turfed the dog out into the woods and drove off.

Nan was beside herself when he told her Yago had gone missing in Calabria. Then a miracle occurred. Three months later when Nan answered the door to a neighbour, in walked Yago. Like everyone else, he had come back to my Nan. It turned out Grandpa hadn’t taken him quite as far as he said he had, but Yago had still found his way home from right across the other side of Milan.

I used to sit next to Nan and put my head on her generous chest and she’d talk quietly and scratch my head. I would fall asleep to that and her voice. It was lovely. It felt comforting. I didn’t know what she was thinking about. Or what she was plotting.

While I was at school, Nan and Dad were also getting lessons: about other ways to make money, including the Italian gangster growth industry – kidnapping. Huge worldwide headlines revolved around the abduction for ransom of John Paul Getty III. His father ran the Italian end of the family oil business from Rome and he’d grown up there. And that’s where he was snatched in July 1973. The kidnappers from the ’Ndrangheta wanted 17 million US dollars for the sixteen-year-old’s safe return.

The family, headed by John Paul Getty I, believed it was a hoax. The next ransom note was held up by a strike by Italian postal workers. The ’Ndrangheta decided to emphasise their seriousness. In November 1973 an envelope was delivered with a lock of hair, a human ear and a note saying: ‘This is Paul’s ear. If we don’t get 3.2 million US dollars within ten days, then the other ear will arrive. In other words, he will arrive in little bits.’

Astonishingly, the boy’s fabulously wealthy grandfather continued to negotiate. Finally, he paid 2.8 million US dollars and his grandson was found alive in southern Italy in December the same year. No one was ever arrested.

Everyone in my family took great interest in the case. Nan and Dad saw it as part of the Wild West that some areas of Italy were turning into. And an opportunity: not to get involved directly with their ’Ndrangheta brethren in the South, but to exploit the situation.

It was only a few years after the ‘French Connection’ – the huge operation that trafficked heroin from Marseilles to New York, which was turned into the 1971 Oscar-winning movie – and the stories of the profits involved remained legend. While the Italian authorities, politicians and carabinieri were focused on the plague of kidnapping, their attention and resources were taken away from drug trafficking, now the other booming business of the age. For Nan and Dad the mechanics were exactly like dealing in cigarettes. The big difference was the product. It was much, much more international and profitable, a multi-multi-million dollar industry.

And lethal for all involved.

CHAPTER FOUR ROOM SERVICE (#ulink_99ff54e1-5ae8-5c46-9606-29e4957eaceb)

‘We seek him here, we seek him there…

Is he in Heaven? – Is he in Hell?

That demmed, elusive Pimpernel.’

BARONESS EMMUSKA ORCZY,

THE SCARLET PIMPERNEL, 1905

Dad was a captain of the new industries, a crime lord, and was acting and living like one. He was turning into a proper Godfather, with scores of soldiers under his command. He seemed to be everywhere but nowhere. He was always wanted by the police for something, even if it was just some petty crime. He was never in one place for long – he scowled out of many passport photographs. The family knew him as ‘Gypsy’ because he criss-crossed the borders of Europe and into Turkey and North Africa.

His power base was Milan. Companies, bars and restaurants were on the payroll, as well as, most importantly, the authorities. This was Nan’s speciality, her business version of tender loving care – bullshit and cash, and lots of both. In pecking order she tied up the lawyers who brought in the magistrates who knew the right judges to approach and fix. She flicked through the corruption process like a pack of cards.

And Dad was just as quickly shuffling his affections. It was rare that he had Italian girlfriends. They arrived on his arm from all over the planet. Mum made sure she had good relationships with his girlfriends now, for she wanted me to stay close to him and she wanted to be comfortable with the girls if I was going to spend any time with them. It wasn’t so difficult for Mum because she had never really loved Dad anyway. She just let go. She was never real friends with him; they tolerated each other because of me.

I got on with most of his girls. Melanie, whose father was a bigwig in the RAF, even took a comb to my nits, which is beyond the call of girlfriend duty. I stayed with her and Dad a few times. I loved the sleepovers and being close to my dad. Dad being there was the most important part of the visits. There was a subliminal feeling I could not experience with any other person. That father and daughter connection. It was different and exciting to be with him. Dad was always very affectionate. He’d mess around with me, we’d have fun. All his girls made a fuss of me, and I liked that.

There were lots of them but Effie the Paraguayan – Miss Paraguay – was special. She looked like a proper Inca woman and behaved almost like a man. She had one of those Aztec top haircuts, and she sat there at my Nan’s smoking a cigar! The family all thought this was great.

Dad lived well. He moved into a luxurious apartment in Milano 2, a residential set-up in Segrate, a new town built by one of Silvio Berlusconi’s companies. It was traffic-free, with bridges and walkways, a gym and a lake in the grounds. It was very upmarket and far removed from the lifestyle Mum and I had. But if Mum ever said anything about this, he retorted, ‘My mother’s looking after you, isn’t she?’

Yet Dad didn’t always get it all his way. He was seriously involved with a stunning French girl but she took a fancy to his sister, my Auntie Mariella. They used to come to my mum’s to be together, to get it on. I came home from school one day to find them in the back of our blue Mini with the white roof. ‘What are they doing?’ I wondered. ‘Why is my dad’s girlfriend in there with my aunt?’

Much as Mum tried to keep it quiet and help, Dad found out and gave my Auntie Mariella a right kicking up the bum; he broke something on her spine, almost crippling her. He didn’t do anything to his girlfriend. Family weren’t meant to betray you.

I was puzzled about it in a little kid sort of way. I couldn’t understand why everyone was upset. Mum told me not to say anything about seeing them together. She probably thought ‘Up yours!’ to my dad. I hope so. No one else would have dared do that.

Dad was doing whatever he wanted, whatever he felt like, but he was too much of a showman and Nan’s payoffs couldn’t guarantee one hundred per cent protection. In 1974 there was a sudden clean-out at City Hall and the appointment of a new police chief with his own set of magistrates. It takes a little time for corruption to seep through the system so, against the odds, a warrant was issued charging Emilio Di Giovine with handling stolen goods. The hunt, the game, was on.

Nan’s apartment is in a courtyard block of about twenty homes. It’s quite a walk from corner to corner. When the police came for my dad one day he thought he was being clever and stole quickly over to the opposite corner from Nan’s. He walked straight into the cops.

They had no photograph of their suspect. They stopped him. Looked at him. Then asked: ‘Do you know who Emilio Di Giovine is?’

‘Oh yes, I’ve heard of him.’

‘What have you heard?’

‘He’s a right one, him.’

‘Do you know if he’s in the area?’

‘I think I saw him about twenty minutes ago.’

‘Do you know where he is?’

Dad could see police trooping into Nan’s. He pointed across the street: ‘He went that way, I think.’

‘Right, thank you.’

Dad had the girlfriend of the moment stashed around a corner. He grabbed her, jumped on a tram and was off. That was his style of stunt. He wouldn’t panic and start running. He would – and could – think on his feet. He would face them up, take the mickey. He loved it.

The newspapers compared him to gentleman thief Ars?ne Lupin, a fictional and glamorous French criminal who’d been turned into a cartoon character when I was growing up. The people he gets the better of, with lots of style and colourful flair, are always nastier than Lupin. He’s a Robin Hood-style criminal, like Raffles or ‘The Saint’. Lupin! It all added to the cult revolving around Dad.

Still the press kept searching for new descriptions of him. After his next exploit he was compared in the same sentence to Lupin and Rocambole, another popular fictional antihero. Rocambolesque is the tag given to any kind of fantastic adventure. And Dad had many Rocambolesque moments.

The flamboyant publicity just brought more pressure on the cops to get Dad off the streets. Finally, in the summer of 1974, when he was twenty-five years old, they got him into Central Court on robbery charges. He was sentenced to a year in San Vittore prison, Milan’s number one jail, which is renowned for its security.

Dad had as much regard for that security as he had for the law. He was Mafiosi. He’d been inside for only five weeks when his brother visited him. Francesco is five years younger than Dad but looks like his twin. Dad was fed up with being caged.

He and Uncle Francesco talked for a time and then Dad asked him to change sides at the visiting table, to come over and sit in the inmate’s chair for a moment. And wait. In an instant Dad walked over to and out through the visitors’ exit. The next thing Uncle Francesco was being taken into the slammer, to Dad’s cell.

He pleaded: ‘What’s going on? I’m Francesco Di Giovine, not Emilio Di Giovine!’

Finally, the guards clicked. The brothers had swapped.

‘I didn’t know what he was doing. He was so depressed. One minute he was there, the next minute he was telling me to switch seats. And then he was gone.’ That was Uncle Francesco’s bumbled explanation of Dad’s jailbreak, his stroll out of San Vittore, making him able to celebrate being a free man. At least a free man-on-the-run. Typical Dad.

The prison thought it was a set-up but the only person set up was Uncle Francesco. His story was dismissed and he was kept in jail for three months for aiding a jailbreak.

When Nan heard what had happened she exclaimed: ‘Oh, that bloody son of mine.’ No one knew whether it was praise or criticism.

For the front pages it was: ‘Rocambole a San Vittore.’

As they were writing the headlines, Dad was on a train out of the city. He went south, staying with friends, and then from Rome he made some phone calls. One was to Melanie Taylor, who had returned to England when her Continental dance tour was over.

‘My sweetheart! My love! I can’t live without you! I’m flying over to see you. I must be with you.’

He laid it on with a trowel. It was the perfect escape route, a ready-made safe haven. Dad moved to Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, to link up with Melanie, and got a job at the Huntingdonshire Hotel where she worked. He’d never worked in a hotel in his life, he’d never worked legitimately, but he swiftly moved up the ranks and was appointed assistant manager in charge of a huge staff.

One evening in the bar he got into conversation with Giuseppe Salerno, who was also from Milan. Understandably, they got on well and had much to talk about. Salerno was butler to the Earl of Dartmouth, who was staying with friends in the area. Over the hotel’s fine wine Dad and he became great mates. Salerno would drop in to the hotel when he could, or Dad and Melanie would visit him in London at the quiet and elegant Westbury Hotel in Clifford Street, near the Earl’s Mayfair home. This was the house Giuseppe Salerno ran, and his duties included the security of the silverware storeroom. He had the key to lock it. And unlock it.

Which is what he did on a rainy November evening when the Earl was at a charity dinner.

Dad turned up, they bundled out the silver jewellery, plates and cutlery valued at ?30,000. Dad drove off back to Huntingdon leaving his new friend Giuseppe tied up and gagged in the entrance hall. It looked like a perfect robbery.

It was for Dad. Not for anyone else. When the Earl returned from his evening, he found his manservant apparently assaulted and robbed, his family silver out the door. Thieves! Robbery!

Melanie helped Dad hide the silver, wrapped in blankets, in a cellar at the hotel. It would be sold when the heat died down. But Giuseppe wasn’t born to crime. He wasn’t injured, there was no sign of forced entry. To the police it looked as though the butler did it.

Giuseppe tripped himself up again and again during his police interviews. After yet another contradiction, he cracked. He pointed the finger at his fellow Italian and the hiding place of the silver. When the police reached the hotel they confronted Melanie. She wouldn’t say where the silver was and it took them three hours to find it. They never found Dad. He was on the run again. When the Cambridge police ran the name Emilio Di Giovine past Interpol and the carabinieri they got an impressive criminal CV in return.

Yet by the time the case reached the Old Bailey in London on 11 August 1975, their man was long, long gone. But his lover was there. Melanie Taylor admitted ‘dishonestly assisting in the removal or retention’ of the stolen silver.