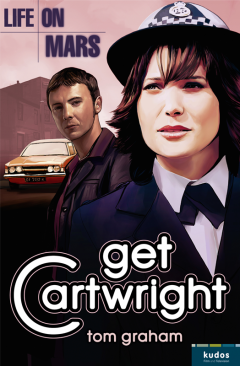

Life on Mars: Get Cartwright

Àâòîð:Tom Graham

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:229.39 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 267

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 229.39 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Life on Mars: Get Cartwright

Tom Graham

Time to leap into the Cortina as Sam Tyler and Gene Hunt roar back into action in a brand new installment of Life on Mars.‘Women in the Force?! It’s against nature! Just look what happened here when they let Cartwright in. Like bloody Yoko, she’s been.’The team at CID is falling apart. Internal conflicts are stretching loyalties, wrecking friendships and turning A-Division against itself. And somehow, with their department splitting like Rod Stewart’s tightest trousers, DCI Gene Hunt and DI Sam Tyler must deal with a case that is leaving dead coppers all over the city, threatening to destroy the mighty Guv’nor himself, and sees Annie Cartwright pursued by a killer who will let nothing stop him – not even death.

Get Cartwright

by Tom Graham

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u9fb71281-5c66-5d58-a4cf-4f6e2918b156)

Chapter One: Shadow of the Past (#u7ab2682e-44cf-5e54-bd17-59c8f8eba247)

Chapter Two: In Extremis (#u140feaee-6529-541f-b2fa-818b4bf1890e)

Chapter Three: One Spent Cartridge (#u5651f03d-a958-5593-a60c-2ecee1488143)

Chapter Four: Sleeping Dogs (#uf04f2641-abcb-5338-a4f1-1757b7665de9)

Chapter Five: Gary Cooper (#u170c8d8e-cb2a-587a-b540-b48c87c1c034)

Chapter Six: Human Remains (#udd18581c-ac31-56e9-a013-aa756f49bb24)

Chapter Seven: This is Diplomacy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: Carroll (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Saucy Jack (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Westworld (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Lost and Found in Lost & Found (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Gene, God and the Meaning of the Western (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: A Quiet Drink (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: Dead Tone (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: Dreams of Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: Cop Killer (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: Duke of Earles (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: It’s Complicated (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: Death of a Cortina (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: Gene Hunted (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: Clive Gould (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Alamo (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: Siege at Trencher’s Farm (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four: Hellfire (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five: Yellow Brick Road (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six: Into The Emerald City (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The End (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Life on Mars? (#litres_trial_promo)

The W6 Book Caf? (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Tom Graham (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE: SHADOW OF THE PAST (#ulink_399d79ab-641c-5eb7-bdfd-139d83c23654)

It was Sunday morning. Manchester was drowsy and still. And DI Sam Tyler was staring death in the face.

My God …! It’s him …

His blood had frozen in his veins.

Don’t run. Stand your ground.

Sam’s heart was hammering in his chest.

This is it. This is the showdown. Don’t run – be a man – it’s time to finish this thing here and now!

The silent confrontation between him and death had been as sudden as it was unexpected. Sam had been walking through the city on a typically dead Sunday morning. Manchester was lying in, its curtains still drawn, its head under the covers, refusing to budge. Here in 1973, Sunday trading was still just a promise – or a threat – that lay in the future. Apart from a few corner shops and wayside cafes, all the shutters were down. Hardly a car moved in the streets. An elderly man walked his elderly dog. A solitary council worker gathered up discarded cans of Tennent’s and stinking chip papers. And through this, Sam had made his way, lost in his own thoughts.

Hurrying past the Roxy cinema, a sudden movement had caught his eye. He glanced up – and at once he gasped and stumbled to a halt. Stepping out noiselessly from the dark fa?ade of the cinema came a shadowy figure, blank-faced and featureless. It positioned itself in Sam’s path, standing motionless in front of a gaudy poster for Westworld, which remained visible through its hazy, insubstantial body. Grotesquely, Yul Brynner’s face – falling away like a mask to reveal robot mechanics underneath – could be seen where the shadow’s own face should have been.

Sam knew at once what – or rather who – that phantom was. He knew the aura of horror that hung about it, had experienced before the primal terror that surrounded this dreadful apparition.

Running a dry tongue over dry lips, Sam said as calmly as he could: ‘So. Looks like you’ve found me, Mr Gould.’

There was no sign of response. Yul Brynner glared back at him through the blank mask of the Devil in the Dark.

Sam tried to pluck up the courage to take a challenging step towards this thing of darkness. But his feet would not obey him. He remained rooted to the spot. Acting tougher than he felt, he said: ‘How are we going to do this? Do we fight? Or do you just zap me with a death ray? Whatever it is, let’s do it. Right now. Let’s finish this.’

Brave words. But he felt anything but brave. A bead of sweat rolled down Sam's face.

The shadow shifted its position, and now, through its hazy form, Sam could see the Westworld poster’s tag-line, perfectly readable through Gould’s chest:

‘Don’t just stand there,’ Sam said, lifting his head and refusing to be cowed. ‘You want Annie? Forget it. You’re not getting her. She’s with me now, you filthy, bullying, murdering bastard. You’re never going to lay so much as finger on her ever again. You and her are history, done with. But you and me, Mr Gould, we have business to finish.’ He raised his fists. They felt puny and weak, like the fists of a child. ‘So let’s get on with it.’

Clive Gould, the Devil in the Dark, remained still and silent, an insubstantial shadow, a dark, hazy stain upon the air. But Sam could still recall the broad-nosed, snaggle-toothed face of Clive Gould from that awful night he had witnessed the murder of Annie’s father, PC Tony Cartwright. In dreams and waking visions, the Test Card Girl had shown him more of Gould’s cruelty, the sickening treatment Annie had suffered in life from this brute, the beatings, the assaults, the psychological torture. And although he had not seen it for himself (thank God), he knew that it was at Gould’s hands that Annie had died. She had died, just as Sam had died, and Gene Hunt and all the rest of them, and wound up here in this strange simulacrum of 1973 that lay somewhere between Life and the Life Beyond.

And at some point Clive Gould died too, Sam thought. But unlike Annie, he shouldn’t have come here. His place was elsewhere. But that hasn’t stopped him. He’s forcing his way into 1973, strengthening his presence here, becoming more and more real. At first, he was a dream, a glimpse of something awful in the dark recesses of my mind. Then I saw him personified in the monstrous body tattoos of bare-knuckle boxer Patsy O’Riordan. Then, in Friar’s Brook borstal, I saw his face, and I saw how he murdered Annie’s father.

And now – right now – I’m seeing him again. A shadow – a ghost.

Sam frowned, tilted his head, thought to himself.

‘You’re not saying very much, Mr Gould. What’s the matter? Don’t you want to kill me here and now? Or is it … is it that you want to, but you’re not strong enough yet?’

The shadow stirred at last. It seemed to push back its shoulders, as if about to attack. But Sam sensed it was all for show.

‘I’m right,’ said Sam, and he felt emboldened. ‘You’re not strong enough to beat me yet. You’re just trying to psych me out before the showdown. You sad, pathetic bully. Well … you might not be ready for this fight, but me …’

Sam lunged forward, hurling a blow at Gould, putting all the weight of his body behind it. He lost his balance and staggered forward, righting himself at once and throwing up his left arm to deflect a counter-attack. But no attack came. The street outside the cinema was empty. Sam stared at Yul Brynner, and Yul Brynner stared back, but of Clive Gould there was no sign.

‘Run if you want to!’ Sam shouted into the empty street. ‘I’m not running anymore! I’m done with running. I’m coming for you, Gould! I’ll find you, and I’ll beat you, and I’ll send you back to the hell you came from!’

His blood was up, he was ready for battle – but his enemy had quit the field. Sam brought his breathing under control and unclenched his fists. He wiped the sleeve of his leather jacket across his glistening forehead. His knees were shaking.

Despite the fear that Gould’s ghost-like appearance had instilled him, Sam felt a strange surge of hope and defiance rising up from deep within him. Gould was getting stronger, but he still didn’t have what it took for the final duel. He would delay the final confrontation until he was more powerful – unless Sam could track him down before then and finish him once and for all.

And I can do it! If I can draw him into a fight before he’s ready for it, if I can provoke him into attacking me too soon … I can do it! I can WIN!

The sense that things were moving towards an endgame between these two implacable enemies renewed Sam’s energies, even revived his spirits. Victory – or at the very least, the possibility of victory – was at hand. The chance was coming for Sam to dispel Gould forever. He had no choice – he had to win this fight; the price of failure was too high. And when he at last defeated Gould, his and Annie’s future together would be wide open, like a shining plain beneath a golden sun, just as Nelson had shown him in the Railway Arms.

‘I’m not here to carry your burden for you,’ Nelson had told him. ‘That’s for you and you alone. Be strong! It’s the future that matters, Sam. Your future. Yours and Annie’s. Because you two have a future, if you can reach it. You can be happy together. It’s possible. It’s all very possible.’

Possible – but not guaranteed.

‘“Possible” is the best odds I’m going to get,’ Sam told himself. ‘Perhaps I can improve those odds with a little help. But who can I turn to?’

At that moment, he stopped, glancing across at a grimy, gone-to-seed, urban church, out of which slow, wheezing music could just be heard. The organist was limbering up before the service. It took a few moments for Sam to place the tune – he hunted through his memory like a man rifling through a cluttered attic – and then, quite suddenly, he found what he was after.

‘Rock Of Ages,’ he muttered to himself. And from somewhere at the back of his brain, words emerged to join with the tune:

While I draw this fleeting breath,

when mine eyes shall close in death,

when I soar to worlds unknown …

‘Something something dum-dee-dum, rock of ages, cleft for me.’

Like photographs in an album, old hymns had a potency that no amount of rationalism and scepticism could entirely stifle. Deep emotions were stirred – part nostalgia, partly unease, part regret, part hope. Sam thought of his life, and of his death – and of Clive Gould emerging from the darkness – and of Nelson, breaking cover to reveal that he was far more than just a grinning barman in a fag-stained pub – and he thought of Annie, whose memory, as always, stirred his heart and gave his strange, precarious existence all the focus and meaning he could ask for.

Despite everything – the threats, the danger, the approaching horror of the Devil in the Dark – Sam felt happy. He knew it wouldn’t last, but as long as it did, he let the feeling warm him, like a man in the wilderness holding his palms over a campfire.

Sam turned away from the church, strolled across an empty street devoid of traffic, and ducked into Joe’s Caff, a greasy spoon which served coffee like sump oil and bacon butties cooked in what seemed to be Brylcreem. There were red-and-white checkered plastic covers on all the tables, bottles of vinegar with hairs gummed to the tops, and ketchup served in squeezy plastic tomatoes. Joe himself was a miserable, bolshy bugger who covered his fat belly in a splattered apron and never cleaned his fingernails. He let ash from his roll-up fall into his cooking, and checked to see if food was ready by sticking his thumb into it.

Sam loved the place.

‘Morning, Joe,’ he said as he strolled in, enjoying his brief inner-glow of happiness. ‘Any news on that Michelin star yet?’

Joe grunted wordlessly back at him. He was shoving meaty objects about in a pan, presumably preparing them for human consumption. From the portable transistor radio balanced above the stove came the strange, melancholy strains of Elton John’s ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.’

‘I’ll have a skinny Fairtrade latte to drink in please,’ said Sam. ‘And a peach and blueberry muffin, and a bottle of still mineral water. Actually, come to think of it, I’ll go for the deep-fried heart attack and a cup of black stuff so gloopy I can stand the spoon up in it.’

Joe looked at him like he’d spoken in Norwegian, so Sam clarified: ‘The full English and one of your unique coffees; quick as you like.’

A jabbed finger and a grunt told Sam that he was to take a seat, so he settled himself facing the door, waiting for Annie and his breakfast, whichever arrived first. He had suggested meeting her here partly because his own place was such a tip that he was ashamed for her to see it, but mainly because Joe’s Caff was the sort of place that cheered you up. It was hard to stay too depressed when you were pumping ketchup out of a plastic tomato. And it was clear that Annie needed a little light in her soul at the moment. Since the riot at Friar’s Brook, and their close shave with knife-wielding borstal boy Donner, she had become withdrawn and preoccupied. Long-buried memories were returning to her; memories of her life before this one, of her father, of an Annie Cartwright very different from the one she was today. It was all still hazy, but she was starting to suspect that all was not as it seemed here in 1973, and that Sam’s strange stories about her past and her family might be more than just fantasies.

I’m going to explain everything to her, Sam thought, watching the door. It won’t be easy – for either of us – but it’s the right thing to do. And with Clive Gould breathing down our necks, she’s got no choice but to understand.

Through the open doorway, Sam could see the church across the road. The wheezing music had stopped, and a straggle of worshippers was now wandering in. Sam watched the desultory handful of OAPs as they headed through the graveyard and in through the church door. It was a typical Sunday-morning turn out. And yet, the sight of it tugged at Sam’s heart. He was hardly a religious man, but that plain, threadbare, C of E church with its leaky spire and unkempt graveyard and its smattering of a congregation spoke to him of Life and Death, of worlds beyond this one, of higher purposes and plans played out in mysterious ways. It reminded him that 1973, like Lieutenant Columbo, was only a shambling mess on the outside: behind the ruinous fa?ade, wheels were turning, great forces were at work, high stakes were being placed.

‘Ee-yar,’ grunted Joe, and he slammed down a plate of runny eggs, fatty lumps of meat, and fried bread glistening with grease.

‘Is this my breakfast or something you just coughed up?’ Sam asked. And as Joe turned away he added: ‘Hey, before you disappear, tell me – do you know anything about old watches at all?’

‘Wrote the book on ’em,’ said Joe sourly, and he peered down at the gold-plated fob watch Sam had rested on the table. ‘Antique, is it?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘Take it down the market, see if someone stumps up a couple of bob.’

‘I’ve no intention of selling it,’ said Sam, closing his hand protectively around the watch. ‘I’m not parting with him, Joe. There’s something very special about it.’

‘You want to get the case replaced. Looks like somebody’s sat on it.’

‘Nobody sat on it,’ said Sam. He ran his finger over the dent that Donner had made with his kitchen knife when he’d lunged at Sam. It had saved his life once already. Maybe it'd do it again.

Utterly disinterested, Joe plodded back to his greasy pots and pans and joylessly started frying a few eggs.

Annie suddenly appeared in the open doorway, dressed in a wide-collared, canary-yellow shirt under a brown suede coat. She paused and looked in. Sam could tell at once something was wrong. Her face was pale, her eyes wide and anxious. When she sat down across from him, she said nothing, just folded her arms defensively.

‘Hi,’ smiled Sam. But Annie just frowned worriedly at him. ‘You’re very tense. Has something happened?’

Annie shrugged.

Thinking of the shadowy ghost that had confronted Sam outside the cinema, Sam asked anxiously: ‘Have you … seen something?’

‘I’m just not feeling right,’ she said.

‘Are you ill?’

‘I don’t know. I just know I’m not right.’

‘Let me order some revolting food for you,’ Sam suggested. He indicated the congealed filth on his plate. ‘You want to join me in a full English? It’ll take your mind off things. Not in good way, but it will take your mind off things. Go on, have a dip with one of my soldiers.’

But there was no response from Annie. She was not in a joking mood. Now that Sam looked at her more closely, she seemed shell-shocked.

‘Talk to me,’ he urged her gently.

‘I’ve been digging into the old police files from the sixties,’ said Annie.‘I needed some information, but the files were in a mess, so I started trying to sort ’em out, get ’em in order. God knows, nobody else in that place is going to do it.’

‘Well ain’t that the truth.’

‘So, I started going through it all. Everything was all filed badly and mucked about with. At first I just thought it was just the usual thing, people being careless, sticking reports in the wrong folders and not bothering to label things right. But then I noticed there were gaps, Sam – gaps like there were things missing on purpose.’

‘You’re saying those files have been tampered with?’

‘I’m sure of it, Sam. Somebody’s been covering things up.’

Sam nodded: ‘There were a lot of coppers on the payroll of villains back then, far worse than today.’

‘And I think I can name a few of them. There’s the same characters who keep cropping up, all of them in CID, all of them in relation to those gaps in the files or with reports that don’t quite make sense. I’ve got their names.’

She placed a sheet of paper on the table.

Sam read it out: ‘DCI Michael Carroll, DI Pat Walsh, DS Ken Darby. Any of them still serving in CID?’

‘No. They’re all retired now,’ Annie said.

‘The corrupt ones always retire. Mmm – these names don’t ring any bells for me.’

‘Nor for me, Sam. But I wonder if the Guv remembers them?’

It was possible. DCI Gene Hunt must have been working his way up through the ranks of CID at the same time as these men were around.

‘I wrote these names down so I wouldn’t forget,’ Annie went on. ‘But there’s one name I can hardly forget – the name of a uniformed copper working at the same time as these three.’

‘Let me guess,’ said Sam. ‘Cartwright. PC Anthony Cartwright.’

Annie looked at him with wide, confused eyes, and then dropped her gaze and nodded.

PC Cartwright. Annie’s father. Sam had seen him, met him, spoken to him – and then watched him die at the hands of Clive Gould, the villain who had all these coppers and detectives on his payroll. Sam had seen it all, though it had happened ten years ago. He had been there.

Choosing his words carefully, Sam asked: ‘What can you tell me about Anthony Cartwright?’

‘I looked him up,’ said Annie. ‘He was a uniformed officer, quite young. Something happened to him, and he died. I think there may have been some sort of a cover-up.’

‘But the name, Annie. What does it mean to you?’

‘I … I don’t know what it means to me, Sam. When I saw it, I tried to think if I had any relatives with that name. Uncles, cousins. But … I couldn’t think of any, Sam. I mean, I couldn’t think of any, no names at all! I couldn’t remember nothing, Sam! Not me mum’s name, not me dad’s – nobody! I tried, but my mind was a blank. It was like I was going mad.’ Annie ran a hand over her forehead, and let out a shaky breath. ‘I got really scared. But then, looking at the name again – PC Anthony Cartwright – it played on my mind …’

‘Did memories start coming back?’

‘Not memories as such, just … impressions. Feelings. Echoes of things. God, I don’t know, I can’t explain it.’

The same thing will happen to me if I stay here long enough, thought Sam. This place – this 1973 us dead coppers find ourselves in – it takes us over eventually, erodes our memories of the life we used to lead, makes us forget everything except the here and now. But those memories of what we used to be are still in there somewhere – buried deep – waiting to be unearthed.

‘I’m really confused, Sam,’ Annie muttered.

‘Believe it or not, I completely understand you,’ Sam replied.

Annie looked at him intensely: ‘Yes. I think you do. You know things, don’t you.’

‘Yes. I know things.’

‘Something’s going on, isn’t it. Something weird.’

‘Pretty weird, Annie, yes.’

‘Then help me,’ Annie urged him. ‘Tell me why I can’t remember nothing. And tell who you are. And who I am! And where the hell we are!’

Sam hesitated. It was a long story – long and mysterious, and full of things he didn’t understand and dark corners where real horror lurked. Where to begin?

Slowly, he took a deep breath, preparing himself for an explanation he had no idea how he was going to phrase. But he only got as far as one word.

‘Well,’ he said. And then, without warning, he was on his feet, staring past Annie through the open door of Joe’s Caff. ‘Oh my God …’

‘Sam? What is it?’

‘A fella …’

‘A fella?’

‘With a gun. I've just seen a fella with a gun.’

‘What? Where?’

‘Right there! Walking into the church! I just seen a fella with a gun walking straight into that church!’ Sam ran for the door, shouting: ‘Joe! Dial 999! Now!’

Joe stood and gawped, slow-witted as a Neanderthal, so Annie shoved past him and grabbed the phone as Sam raced out into the street. He heard Annie’s voice calling after him – Don’t go, Sam, stay here, wait for back up! – but he couldn’t stop himself. His instincts had kicked in.

Is this the final showdown? Sam wondered as he sprinted across the street and through the little churchyard. Was that Gould I saw? Is he ready now? Is this how we’re going to finish this business between us – in an armed stand-off in a church? So be it, then. If that’s what he wants, let’s do it. Let’s do this thing! Let’s finish it once and for all – right now!

He reached the arched entrance of the church and flung the doors open before he could talk himself out of it.

CHAPTER TWO: IN EXTREMIS (#ulink_fa264e4b-c88c-5324-9788-30ed8b0a1259)

Sam dashed into the church and skittered to a halt. Dotted about in the pews were various elderly people, old ladies mostly, waiting for the service to begin. But Sam’s attention was fixed on the man who stood at the very back of the church, just inside the main doors, only feet away. He was in his sixties, dressed in a denim jacket, orange nylon shirt, and beige corduroy slacks. He had a hard face, square-jawed and deeply lined. His hair had receded to a collection of wiry, grey curls about his ears. Motionless and silent, he stood at the end of the aisle and glared fiercely ahead.

He’s certainly not Clive Gould. So who the hell is he?

Sam looked down, and saw the revolver gripped tightly in the man’s white-knuckled hand. His finger flexed repeatedly on the trigger.

This guy’s right on the edge. He’s all nerves. Is he deranged? Is he high on something?

‘Hey there,’ Sam said softly. He edged carefully forward. ‘You look strung out.’

The man ignored him. His jaw muscles convulsed.

‘Maybe I can help you,’ Sam said. ‘It’s okay. I’m not going to try anything. My name’s Sam.’

There was a flicker in the man’s eyes, and he turned his head suddenly to turn that furious gaze upon Sam.

‘Sam?’ the man grunted. ‘Sam Tyler? DI Sam Tyler?’

Oh God, have I nicked him in the past? Sam thought, trying to place the man’s face. Has he got a grudge against me? Should I just grab that gun off him and pin him down before he makes a move?

‘Yes, I’m DI Tyler. Have we met?’

‘So … it’s you …’

An old lady turned round in her pew and shushed angrily.

Sam inched closer to the man: ‘Listen, why don’t you give me the gun and we’ll talk outside. There’s a caf? just across the road. I’ll get you breakfast.’

‘SHHH!’

The vicar had appeared, a small, round-shouldered man with pebble glasses. He took his place at the lectern and perused his Bible short-sightedly, oblivious to the drama playing out at the back of his church.

The man with the gun was shaking, his jaw muscles clenching, eyes glaring. Whatever he had come here to do, he was on the verge of doing it. Sam had to get him out of there right now. He’d give it one more go with the softly-softly approach but if that failed, he’d wrestle the gun from him by force and keep him pinned till back up arrived.

‘You don’t need that thing,’ Sam whispered, and he held his hand out for the gun.

‘It’s all because of you, DI Tyler …’ the man muttered.

‘I don’t know what you mean. Give me the gun and we can straighten everything out.’

‘It should be you not me …’ His voice was almost inaudible now. ‘You’re the one he wants … It should be you …’

‘The gun. Give me the gun. We can’t talk properly until you give me the –’

At once, the man raised the gun – and thrust it against the side of he own head. His eyes were wide and round and bloodshot. A livid vein pulsed along his temple.

‘Don’t do it!’ Sam yelled.

‘SHHH!’ hissed half a dozen old ladies.

The vicar peered up, mole-like.

‘My name is Detective Chief Inspector Michael Carroll,’ the man with gun declared, speaking loudly and clearly like he was giving a public address. ‘I worked for Manchester CID. I served this city for twenty-five years. I arrested villains. I made the streets safe. I am a good man!’

‘SHHH! SSSSSHHH!’

Sam’s mind was reeling. DCI Carroll. That name was on Annie’s list of corrupt ex-coppers from the sixties.

No coincidence, Sam thought, his mouth going dry. This is no bloody coincidence.

‘I am a good man!’ Carroll insisted, his voice growing louder. ‘I AM A GOOD MAN! I do not deserve this!’

The barrel of the gun was pressing deep into the side of his head now, his finger hooked tightly around the trigger. If Sam rushed him, Carroll would blow his brains out before he could do a thing.

‘What’s happening back there?’ the vicar called out, squinting through his glasses.

‘Those boys are playing cop ‘n robbers with a water pistol,’ a phlegmy man growled, not looking up from his prayer book.

‘Well take it outside!’ an old lady barked, banging the back of the pew angrily with her arthritic hand.

‘I’m a police officer,’ Sam announced. ‘I’m a real police officer.’ And then, with more hope than conviction, he added: ‘A situation is in progress but I have got it fully under control.’

‘You know my name, Mr Carroll,’ Sam said, fixing his attention on the man’s eyes, willing contact between them. ‘And I know yours. We’re acquainted. So let’s talk.’

‘I am a good man, and I should be rewarded as a good man!’

‘Yes, you’re a good man, and that’s why you’re going to do the right thing. You’re going to put down that gun.’ Taking a gamble, Sam added: ‘Let’s go across the road, sit down over a coffee, and talk about Clive Gould.’

The name had an instant and devastating effect on Carroll. His face contorted wildly as if he were suddenly in agony.

‘Clive Gould …!’ he snarled. ‘I told that bird I had nothing to say about Clive Gould!’

‘What bird?’

‘Cartwright’s daughter! She came asking!’

Sam’s jaw fell open.

‘Annie?’ he gasped. ‘You’ve been talking to Annie?’

The colour drained from Carroll's lined cheeks. His eyes screwed up and filled with tears.

‘I told her it weren’t me, I was nothing to do with what happened!’ he cried, his voice tight and constricted. ‘What the hell else could I say? And then, after she went, he turned up ...’

‘Gould. Clive Gould. He came for you, didn’t he?’

Baring his yellow-stained teeth like a wild animal, Carroll suddenly thrust the gun straight at Sam.

Sam froze.

‘What is going on?’ whinged the vicar, peering myopically.

Carroll glared along the barrel of the gun, grinding his teeth furiously.

‘I am good!’ he growled, his throat tight and constricted. ‘I’m not perfect, but I am GOOD! It should be YOU not me, Tyler! I do NOT deserve this!’

‘Deserve what, Mr Carroll?’ Sam said, in a voice that he fought to keep from wavering. He tried to look past the muzzle of the pistol that was pointing right between his eyes, and instead fixed his attention on the man’s face. ‘Tell me. I’ll help you. We’ll work together. What is it you don’t deserve?’

‘It’s you he wants, not me!’ Carroll snarled. ‘You and her! Oh, I’d blow your head off, Tyler, I’d blow your damned head right off and stop all this … but it’s too late … too late for Pat, too late for me …’

‘Please, Mr Carroll, put away the gun and talk to me. I understand more than you think. I can help you. Together, we can –’

But the vicar was marching down the aisle towards them, peevishly demanding to know what in God’s name was going on.

‘Stay back!’ Sam ordered.

‘I will do no such thing!’ the vicar snapped. ‘Not until you boys tell me what you think you’re d –’

In the next moment, Carroll had the vicar in a head lock, the pistol jammed against the poor man’s face hard enough to send his glasses skittering away across the stone floor.

‘I’m not going to end up like Pat!’ Carroll howled. His voice broke, making him sound like a desperate, wailing child. ‘I’m not going to end up that way! No, no, no, no ...!’

From outside came the clanging of police sirens. Carroll stopped howling and gritted his teeth.

‘Keep them out, Tyler!’ He barked. ‘Nobody comes in here! Anyone comes through that door, anyone so much as sticks his face at a window, and I start killing hostages.’

‘Hostages?’ an old dear piped up. ‘Does that mean none of us can go?’

‘I think it does,’ put in a lady with a hat like a giant powder puff.

‘Oh. Oh dear.’

The vicar struggled against the headlock and issued a series of muffled cries.

‘What is it you want, Mr Carroll?’ Sam asked.

‘Keep them out, Tyler!’

‘I’ll keep them out, Mr Carroll, but if you don’t tell me what your demands are I can’t help you.’

‘I just want to be safe!’ Carroll screamed, tightening his grip on the vicar. ‘I don’t want to be left alone, not with him after me! Now keep ’em out of here! Keep everybody away!’ And then, venomously, he cried: ‘God damn you, Sam Tyler, you bastard, it should be you not me! IT SHOULD BE YOU NOT ME!’

Sam opened his mouth to say something, but Carroll shrieked insanely, and for a moment it seemed that he was going to shoot the vicar and then turn the gun on everyone else. So Sam held up his hands and stumbled backwards, saying: ‘Okay, it’s okay, just stay calm, I’ll see no one comes in, I’ll make sure everything’s cool …’

He backed out into the churchyard, and at Carroll’s command pushed the door closed.

He’s seen Gould … but something happened, something terrible. It’s freaked him out. But what was it? What did Gould do? What did Carroll witness that drove him to this?

Would Annie know? She had evidently been to see him, following up leads she had unearthed in the police files. She was drawn to the story of PC Tony Cartwright, no doubt sensing that there was far more of a connection between her and them than the sharing of surname. Did she know yet that Tony was her father? She must surely be suspecting … and at the same time, she must be doubting her sense of reality, wondering just who she is and where she is.

He turned – and at once ran into a huge wall of camel hair.

‘Morning, Tyler – somebody call Siege-breakers?’

DCI Gene Hunt loomed over him, flinging open his coat to reveal his ridiculous leather body holster, one hand already resting on the grip of his trusty Magnum, ready to draw. Behind him, the road outside the church was filling up with patrol cars and uniformed officers. Men were bustling. Radios were crackling. Police tape was fluttering like bunting between the lamp posts, cordoning off the street.

‘Back!’ Sam ordered.

‘Forward!’ Gene growled, and took a manly stride towards the doors of the church.

‘I said back!’

‘And I said ruddy forward, and I’m bigger than you!’

Sam grabbed him by the lapels and thrust him back.

‘Don’t you shove me, Tyler!’

‘Back, Gene, back back back!’

‘The Gene Genie don’t have no reverse gear, you know that by now!’

‘You’re going to kick off a bloodbath mucking about like this! Now get BACK!’

Sam barged Gene away. The Guv’s face fell into an expression that mixed shock, rage, and explosive indignation into one. His eyes blazed. His nostrils flared. He thrust the Magnum back into the holster and put his fists up.

‘You wanna duke it out, you and me, is that it, Tyler? Well come on then!’

Raising his voice, Sam bellowed at the uniformed officers massing nearby: ‘Everybody get back! We have an armed man in there with hostages! Nobody is to approach the church, nobody is to look in the windows, nobody is to do anything! Back, back, back!’

He waved his arms, shepherding the officers away. Gene watched him, open-mouthed.

‘Ordering plod about is my jurisdiction, Tyler!’

‘For God’s sake, Guv, just grow up!’

‘Oh, so you’re calling me a kid an’ all now, are you? You’re picking the wrong day to tangle my todger. This is Sunday. I shouldn’t even be here. I am royally miffed! I should be home with me tinnies and me feet up waiting for The Big Match. The Genie doth resteth on the seventh day, an’ all that. It was only coz I was hunting in the Cortina for me spare fags that I caught news of this shout on the radio, and being the conscientious DCI that I am, I decided to –’

‘Stop whinging and get back along with everyone else. That fella in there’s on the edge. He’s ready to start blowing the heads off a vicar and his flock at the drop of a hat. So if you don’t want blood on your hands, Guv, get you and your off-white loafers right back!’

Sam shoved and elbowed Gene back through the church yard and onto the pavement.

Annie pushed her way through the bustle of uniforms to get to Sam.

‘You were mad running in there like that!’ she scolded him.

‘He were showin’ off,’ observed Gene, giving Annie a knowing nudge. ‘He’s got his sights set on the contents of your extra-large British Home Stores pants with the reinforced gusset. Different strokes, I suppose.’

‘I’m all in one piece,’ Sam said, ignoring Gene and focusing on Annie. ‘And I got a name. The gunman’s called Carroll – ex-DCI Michael Carroll.’

Hearing the name, Annie’s eyes went wide as saucers.

‘Carroll!’ she gasped.

Sam nodded. He desperately wanted to tell her that he knew she had spoken to Carroll – but in front of the Guv, he decided to keep his mouth shut.

Frowning, Gene looked from Sam to Annie to Sam again, and said: ‘Um, do you want to include your Uncle Gene in this private chinwag? I mean, I know I’m only your boss and superior officer and professional role model and all that …’

‘DCI Carroll’s one of the names on Annie’s list,’ said Sam.

‘Oh aye?’ grunted Gene. ‘Annie’s list of what? Blokes round the department she’s ready to gobble for a quid?’

Annie was too preoccupied with her own thoughts to even hear this. But Sam reacted sharply.

‘Jesus Christ, Guv, that’s bang out of order what you just said!’ he shouted. Then he glanced guiltily at the large cross standing boldly atop the church, backlit by the sun, and mouthed at it: Sorry. In a lower voice, he hissed at Gene: ‘Flippin’ heck, Guv, that’s bang out of order what you just said.’

‘Loosen up, Tyler. I understand the way it is. How else is Inspector Jugs going to get promotion if it ain’t on her knees?’

Sam kept his temper in check, took a moment to gather his thoughts, then explained patiently: ‘Mickey Carroll is a retired DCI. He was on the force back in the sixties. Annie’s been digging into the old records and reckons him and a couple of others were on the payroll of a local villain.’

‘And what’s Annie doing spending her time on cold cases, eh?’ Gene asked, narrowing his eyes and peering at Annie suspiciously. ‘Ain’t we got enough villains on the prowl to keep her fully occupied?’

‘I think there’s secrets hidden in them files, Guv,’ said Annie. ‘Nasty secrets. I got the strong impression that Carroll was corrupt – him and others. DS Ken Darby, DI Pat Walsh …’

‘Pat Walsh!’ Sam exclaimed. ‘Of course! Carroll mentioned the name Pat in there. It’s got to be Pat Walsh, his old DI. Guv, we’re uncovering something here. If Annie’s right, and they’re both bent coppers from the sixties, then I think there’s more than just coincidence going on here. We should track down Walsh – ten-to-one he can shed some light on what’s happening inside that church right now.’

‘Well this is all ‘appening a bit sharpish,’ said Gene.

‘You can thank Annie for that, Guv.’

Gene sneered: ‘Don’t lay it on with a trowel, Tyler.’ He pulled his coat straight and added: ‘Okay. This DI Pat Walsh. Where do we find him?’

‘57, Streeling Street.’ It was a uniformed officer standing close by who spoke up. Sam, Annie and Gene turned to look at him. The bobby added: ‘It’s a call that came through right before this one. Mrs Walsh, 57 Streeling Street, reporting a break-in and possible missing person – her husband, Patrick Walsh. Some of the other lads went to see to that one. I got sent here.’

Sam reacted at once: ‘Let’s get over there, Guv – pronto!’

He sprinted towards the Cortina where it sat amid the patrol cars, gleaming in the mid-morning sun. Annie ran with him. They leapt in, Sam in the front passenger seat, Annie in the back – and then waited while Gene sauntered arrogantly over, paused to light a cigarette, adjusted the leather strap of his string-back glove, then pretended to forget which pocket he’d put his car keys in. He was not to be rushed – least of all by his minions and flunkeys.

‘Come on, come on!’ Annie hissed from the back, glaring through the windscreen at Gene.

This isn’t a police investigation for Annie, any more than it is for me, Sam thought. Annie’s unearthing her own identity here – and all the dark secrets that identity contains. And as for me – this is the start of the showdown, the final face-off between me and Clive Gould, the murderer of Annie’s father, the Devil in the Dark itself …

Without warning, Annie leant forward and slammed her fist into the Cortina’s car horn.

‘Come on!’ she cried.

Gene’s expression changed. His cheeks flushed red. A cold, hard light glittered in his eyes. He threw away his barely smoked fag, stomped furiously over to the Cortina, and flung open the rear door.

‘Out!’ he barked.

‘Oh, let’s just get going, Guv,’ Sam urged him.

‘I said, out!’

Annie glared up at Hunt, and for a moment Sam thought she might suddenly launch herself at him in a ferocious attack. But no. She angrily clambered out of the car and threw her leather handbag down hard on the ground.

Gene stared into her face and said in a low, dangerous voice: ‘You honked my horn …’

He flexed his hands, making his black leather driving gloves creak ominously.

Annie stared right back at him, her mouth pulled tight, her eyes narrow and enraged. Then she picked up her bag and strode away.

‘Annie!’ Sam called after her, but her only reaction was to rip aside a cordon of blue police tape as she went.

Gene watched her go with an expression like a very pissed off lion – then, slowly, clambered into the driving seat next to Sam. Without saying a word, he fired up the engine, brushed a speck of imaginary contamination from the horn, and hit the gas.

CHAPTER THREE: ONE SPENT CARTRIDGE (#ulink_507da481-2573-5285-8635-9cc514dd8010)

The Cortina howled to a stop outside the bungalow at 57 Streeling Street. There was a patrol car parked by the front drive, inside which a WPC could just be seen, comforting a distressed woman. A PC lurked at the front of the bungalow, licking the tip of a tiny pencil and making notes.

Gene sat behind the wheel for a moment, staring ahead.

‘What’s the story with her, eh, Tyler?’ he asked.

‘Annie’s got things on her mind,’ Sam replied, refusing to be drawn into details.

Gene snorted in contempt: ‘Got things on her mind?! She’s a bird – minds don’t come into it!’ And before Sam could spring to her defence, he added: ‘Do me a big favour, Tyler. Get her sorted.’

‘She’s her own person, Guv.’

‘In her own little head maybe, but not in my department. Stompin’ about, telling me to get a move on, honkin’ my ruddy horn ...!’ A flame of indignation flickered anew at the memory. ‘I don’t know what her problem is, and frankly I don’t give a stuff. But if you don’t rein your tart in, Tyler, I’m gonna throw her over my knee and give her a damned good slippering. And I may not be speaking metaphorically.’

‘Just give her some space, Guv. She’ll be okay.’

‘It’s my horn, in my motor!’

‘I know, Guv.’

‘And I’m the boss! And it’s bloody Sunday and I’m missing The Big Match! Don’t my feelings count for nothing round here?’

‘I’ll have a little chat with her later.’

‘Do that, Tyler – before I have a little chat with her. And you know how my little chats tend to pan out.’

And with that, Gene threw open the car door and clambered out. Sam sighed and followed him.

They crossed to the patrol car. A toothy, rather ineffectual-looking WPC got out.

‘I’m trying to comfort Mrs Walsh,’ she whined. ‘But she’s gone a bit crackers.’

Gene had a look inside the car and was confronted by Mrs Walsh’s face, contorted and mascara-streaked, a bubble of mucus burgeoning in her left nostril as she blubbered and howled.

‘Holy Moly, somebody call an exorcist,’ Gene growled out of the corner of his mouth.

‘What happened here?’ Sam asked the WPC.

‘Mrs Walsh had been away for a few days, visiting her poorly Auntie Janet in London. She came back this morning on the Intercity and found the bungalow wrecked and no sign of her husband. And now she’s panicked and gone mental.’

Mrs Walsh suddenly banged on the inside of the car window and howled. There was lipstick smeared chaotically over her wrinkled mouth and a stalactite of thick snot wobbling from the tip of her long nose.

‘Sprinkle her with holy water,’ suggested Gene. ‘It’ll buck her up or melt her – either way, it can only be an improvement.’

Hunt marched up the little garden path towards the bungalow, Sam striding along beside him.

‘Anything to report?’ he asked the PC at the door, flashing his ID.

‘Bit of a mystery, Sir,’ the copper said. He indicated the front door, which was lying flat in the hallway. It had been ripped clear from its hinges. ‘Somebody came in here full wallop. And it’s no better inside. The place has been trashed.’

‘And what about Pat Walsh?’ Sam asked. ‘No clue what’s happened to him?’

‘Not that I can find,’ shrugged the PC. ‘His missus ain’t being much help, squawking away like that, but to be honest I don’t think she knows nowt anyway.’

Sam stepped inside the bungalow, walking across the wrecked door to reach the hall. Broken glass crunched under his feet. Pictures had been flung from the walls, windows had been smashed, lampshades hung in shreds about shattered bulbs.

‘It’s like a feckin’ whirlwind tore through this gaff,’ muttered Gene, peering about at the wrecked furniture and scattered debris. ‘Or else it was the boys from forensics on one of their piss-ups.’ With the toe of his loafer, he nudged at a carriage clock that lay amid the ruin, its face smashed, its hands twisted. ‘Whoever turned this place over must have been desperate.’

‘Yes, Guv – but desperate for what?’ Sam said, pointing into the bedroom. Mrs Walsh’s earrings and necklaces lay discarded all over the bed and floor. ‘Since when did burglars leave the jewellery behind?’

‘And what about these?’ Gene said, bending down to scoop up the playing cards scattered about all over the floor. ‘What sort of bloke would break in and leave treasure like this lying about?’

‘Playing cards, Guv?’

‘Not just any playing cards, Tyler.’

Gene presented them for Sam to inspect. They were porno cards, each one graced with its very own topless, spread-legged angel. It was all hitched-up denim skirts, brown suede boots, and glossily pouting lips.

‘Well I don’t think they belong to Mrs Walsh,’ observed Sam.

‘I can’t see that crabby mare putting up with these charmin’ lovelies,’ said Gene, perusing the cards one by one. ‘Gotta be Pat’s contraband, eh. His private stash. Fodder for a crafty J Arthur when the missus is off down the Wavy Line. Can’t blame him for that, a fella needs to stay sane. I mean, be honest, there’s no way he’s going to get the horn looking at her dried-up Boris Karloff boat race every night.’

‘Guv, you give whole new depth to the term ‘ungentlemanly’, did you know that?’

Gene suddenly thrust one of the cards towards Sam’s face. It was the four of clubs, depicting a young woman with straight blonde hair sucking her finger whilst unbuttoning a very tight pair of orange corduroy hotpants.

‘Here’s a question, Tyler – and tell me straight: if this bird were your sister … would you be tempted?’

Sam looked flatly at him for a moment and then said: ‘Guv – have you ever thought about being psychoanalyzed?’

Gene perused the card: ‘Got a better set of lungs on her than your Flatty Cartwright. Just think what you’re missing.’

‘Do you think there’s any chance we could conduct this investigation like professional police officers?’

‘Perhaps it’s you what needs his head shrinking,’ Gene said under his breath as he pocketed the cards. ‘A real fella would show at least a scrap of interest.’

Sam picked his way through yet more debris, finding broken tumblers lying about, and a discarded bottle of Scotch on its side, its contents leaking onto the carpet.

‘Let’s try and make sense of all this,’ he said. ‘Scotch bottle – glasses – porno playing cards. And the wife safely out of the way. That tells me Pat had a mate over – a bloke.’

Gene shrugged: ‘Most like. But that don’t get us too far, does it.’

‘It does if that bloke was Pat’s old DCI, Mickey Carroll.’

Sam was piecing things together in his imagination. He imagined Pat Walsh here on his own, his wife out of the house for a few days. Pat calls Mickey Carroll over, or perhaps Carroll just turns up. They need to talk, to spend time together. They have things on their minds.

What? What do they have on their minds?

Was it something to do with Clive Gould? If Annie was right, they had both been in Gould’s pocket back in the sixties. Was something about Gould troubling them? Is that what the two of them wanted to discuss?

He recalled what Carroll had howled at him in the church: ‘I’m not going to end up like Pat! I’m not going to end up that way!’

Did they see Gould, just like I saw Gould? Sam thought. He felt a deep sense of conviction that he was thinking along the right lines – a conviction that came from the fact that Carroll and Walsh, like Sam, were caught up in the machinations of the Devil in the Dark.

Sam took a slow breath, relaxed, and allowed a picture to form in his mind’s eye. Where there was a lack of hard evidence, maybe his imagination, his intuition, his copper’s nose would point the way.

Walsh had the place to himself. He had things on his mind … things to do with Gould. Carroll came over, because he had worries too. Gould was haunting them both in some way. They were disturbed, frightened. So the two of them sat down here, Walsh and Carroll together, playing cards, drinking. It comforted them. They started talking things through, trying to make sense of whatever it was that was disturbing them, and then …

Sam turned, looking back into the hallway at the smashed front door, then glanced about at the shattered furniture, the broken windows, the scattered wreckage. Something came crashing in here, roaring through that front door like an express train and turning the whole place upside down. And then what?

His intuition could not fill in the blank. Whatever happened was beyond his experience to imagine. All he could tell for sure was that Carroll had escaped, but not before he witnessed something happening to Pat Walsh – something awful – something that sent him haring off into that church with a gun in his hand.

‘Looky-here, Tyler,’ Gene said. There was a bullet hole in the wall. Gene peered at it for a moment, then hunted about amid the wreckage at his feet. Bending down suddenly, he straightened up again with something held between his thumb and forefinger.

Sam drew closer and examined it: ‘A spent cartridge.’

‘From a pistol. The same pistol Carroll’s got with him in the church, you reckon?’

‘It’s possible, Guv. We’d need an official ID from ballistics.’

‘Let’s assume for the time being it is from that same gun,’ said Gene, his face pulled into a pinched, pensive expression as he examined the shell. ‘What does this tell us? Did Carroll whack Walsh, is that what happened?’

‘I don’t see any blood,’ said Sam.

‘No. Neither do I …’ muttered Gene, almost to himself. ‘So – he either fired at Pat Walsh and missed. Or else he fired at somebody else entirely.’

Sam imagined the bullet passing straight through Gould’s shadowy form. The image made his stomach tighten.

What weapon will stop Gould? What have I got that can hurt the Devil in the Dark?

Instinctively, he reached the gold-plated fob watch nestling in his pocket. As his fingers felt across the dented surface of the casing, he willed himself to sense some sort of magic power surging out of it, something that intimated that this simple little pocket watch was in reality a talisman, a weapon, salvation.

But he felt nothing. Nothing at all.

CHAPTER FOUR: SLEEPING DOGS (#ulink_deea3f2e-0f95-56d6-a9cc-72978813fb87)

Monday morning. The overhead strip lights of CID were burning and flickering, bathing A-Division in their unhealthy, cheesy glow. Typewriters clacked, telephones rang, great mounds of paperwork leaned precariously on desks thick with fag ash, unwashed coffee cups and crumpled betting slips.

Sam strode into the department, and was confronted by the sight of DC Ray Carling lolling about at his desk. Ray was already on his fourth or fifth fag of the morning. He had draped his corduroy jacket on the back of his chair to fully show off his sweat-stained, eggshell-blue nylon shirt in all its unironed glory. His brown kipper tie hung loosely from his collar, and his top buttons were undone enough to reveal a flash of wiry chest hair.

‘Morning, Boss,’ Ray intoned without looking up. The remains of an egg butty were still visible, clinging to the bristles of his moustache.

‘Ray – seriously – is that any way to turn up for work?’

Ray stared blankly, then glanced down at himself uncomprehendingly.

‘I’m a bloke,’ he said. ‘How the hell else do blokes turn up for work?’

‘Some of them wash, Ray, and change their clothes, and at the very least do their bloody tie up. You look borderline homeless.’

‘I had a wash Saturday,’ Ray rebuked him, lifting his stubbly chin in a display of dignity. ‘And this shirt’s clean on from last week.’ He sniffed his armpit, then looked past Sam and called out: ‘Hey, Chris! I don’t whiff, do I?’

DS Chris Skelton emerged from behind a filing cabinet, dressed in a diamond-pattern tank top and beige slacks. But instead of answering Ray, he came swaggering slowly across the room, his face impassive, his hands held strangely at his sides. Fixing Sam with a dead-eyed stare, he gruffly intoned the single syllable: ‘Draw.’

Sam stared blankly back at him: ‘… What?!’

In the same gravelly voice, Chris grunted: ‘I said draw.’

‘He went to see that flick the other night,’ Ray put in, picking at crusty bits on his shirt. ‘The cowboy one with Yul Brynner where his face falls off at the end.’

‘Westworld?’ Sam asked.

But the moment he spoke, Chris suddenly drew an imaginary revolver and pow-pow-powed it straight at Sam. Despite Sam’s total lack of reaction, a grin spread across Chris’s face. He blew the gun smoke from his finger tip and said: ‘Oh, Boss, you got more holes in you now than a ruddy sieve. I am Yul Brynner!’

‘I see the movie’s fired your imagination, Chris,’ Sam replied. ‘And yes, I admit it’s a bit of a sci-fi classic. But can we leave the gunslinger routine for the pub?’

‘The saloon,’ Chris corrected him. And then, turning to Ray, he added: ‘And in answer to your question – no, you don’t whiff. Not at all. If you do, the fags and farts cover it.’

Sam held up his hands in a gesture of surrender: ‘Hey, fellas, I’m not up to intellectual debate of this calibre so early on a Monday morning. Ray – forget I said anything.’

‘I already ’ave, Boss,’ muttered Ray.

‘Anybody got any news on the siege at the church?’ Sam asked.

‘Last I heard, it were still dragging on,’ said Chris, heading over to his desk. ‘There’s coppers all round the place, but nowt’s happening.’

‘If there are any developments at all – anything – I want to be informed at once. Understood, cowboy?’

‘Yee hah, Boss,’ winked Chris, giving a jaunty Yankee Doodle salute.

‘Understood, Ray?’ Sam added.

‘Nope,’ Ray muttered. ‘I don’t even understand how to get dressed of a morning.’

‘Oh, stop sulking,’ Sam said, striding past him. And mischievously he added: ‘Sometimes, Ray, you’re worse than a bird.’

‘Shoot him for that, Ray!’ Chris urged, and he fell back into his gunslinger stance.

Getting clear of all this idiocy, Sam headed over to Annie who was sitting off by herself, hunting through masses of old police files and making scribbled notes. She barely acknowledged him as he approached.

‘I promised the Guv I would have words with you,’ Sam said gently, half smiling. ‘You overstepped the mark yesterday: you honked his horn. And he was not well pleased. In fact, he was livid, and the only way I could stop him coming after you like a rabid Rottweiler was to promise him I would officially reprimand you for your behaviour. So. There you go. Consider yourself officially reprimanded.’

He grinned at her, but Annie didn’t look up. Her face was serious and intense as she pored over her files, ran her finger down a page of typescript, paused, then made a note. Sam’s smile faded.

The more she looks into those files, the more she starts to see of her forgotten life. It’s coming back to her – slowly, and in fragments, but it’s there.

‘Listen, Annie,’ he said in a whisper. ‘I know you went to see Carroll, that you spoke to him. I haven’t said anything to the Guv about it – in his current state of mind, I think he’d hit the roof. I understand that you feel compelled to find out more about PC Cartwright, but you’ve got to be careful. You’ve got to try to –’

‘I think he was murdered,’ Annie cut in suddenly, without looking up.

‘Who? PC Cartwright?’

She nodded, keeping her head down as she thumbed her way through yet another file.

‘PC Anthony Cartwright died while off duty,’ she said. ‘DCI Carroll compiled the official report on what happened. The report says that DI Patrick Walsh and DS Ken Darby were witnesses to what happened. Together, they testified that they had gone drinking with Tony Cartwright, and that he had admitted to owing hundreds of pounds to a loan shark to pay off gambling debts. Heavy pressure was being put on him to pay back his loan plus yet more hundreds in interest, but he simply didn’t have it. According to Walsh and Darby, Tony Cartwright got drunker and more despairing, until at last he staggered off, distraught. They hung about for a bit and then went after him. They saw him throw himself into the canal, but it happened too quickly to stop him. It took two weeks to start dredging the canal.’

‘Two weeks? Why so long?’

‘There were no qualified divers available, apparently. Eventually the body was found and hauled out. Walsh and Darby testified to what happened, and DCI Carroll signed off on it. Case closed. But look here, Sam … The coroner’s report for Anthony Cartwright. It says that the body was identified by Walsh and Darby, not by Cartwright’s wife. She never saw the body. Carroll wouldn’t let her. According to his report, it was to spare her the trauma because the body was badly decayed. But, Sam, look …’

She shoved the coroner’s report at Sam and jabbed at it with her finger.

‘The name of the doctor who carried out the autopsy,’ she said.

‘Dr F. Enderby,’ Sam read out. ‘That name’s important?’

‘Only because there is no Dr F. Enderby who ever worked as a police coroner or anything else – not here, not in the Midlands, not in London, nowhere! If there was, then he’s done a brilliant job of removing every trace of his existence from the CID files. His name isn’t mentioned anywhere else, not once. Not once, Sam. When I get the chance I’m going to go down the county coroner’s office and see if there’s any mention of him there, but I’m not betting on it. Two weeks to get a diver in, by which time the body’s in too bad a state to be seen by anyone but this non-existent coroner. That ain’t right, Sam. And look at this. It’s a file of bank statements for Cartwright’s current account and building society account at the time of his death.’

Annie thrust the file into Sam’s hands. He opened it.

‘It’s empty,’ he said.

‘The statements are marked as “mislaid”,’ said Annie. ‘No proof that he was ever in debt. And the last person registered as taking this file out of the records office –’

‘– was DCI Carroll,’ Sam finished her sentence for her.

‘And here’s a statement from a man called Terrence Fitch, arrested less than a week after Cartwright’s body was recovered. He was a money lender, a loan shark. In this statement he admits to lending seven hundred pounds to Cartwright at some ridiculous rate of interest, and then threatening to kill him and his family when the repayments stopped.’

‘In fairness, doesn’t that corroborate the official story?’ said Sam.

‘Fitch was arrested by Walsh and Darby, and interviewed by Carroll. His statement was put into the Cartwright file, and after that Fitch disappeared from the records. Completely. No word of him.’

‘Are you saying he didn’t exist?’

‘If he did, he had the same talent for vanishing as the mysterious Dr F. Enderby. Look at all this stuff, Sam – it stinks of a cover-up. Files going missing. A dodgy coroner’s report. A miraculously convenient suspect interview that just happens to confirm the official story. And those same three names cropping up time and again: Carroll, Walsh, Darby.’

‘It certainly feels all wrong, Annie. But …’ He hesitated, fearing that the ears of Ray and Chris were flapping in their direction. Lowering his voice to a murmur, he said: ‘Why is it so important to you to find out what happened to PC Cartwright? Do you feel … close to him in some way?’

Annie paused, chewed her lip, and said: ‘I think so. I’m confused. Why does all this stuff feel so personal?’

‘Has the name McClintock turned up in those files?’ Sam asked. Here in this otherworldly 1973, McClintock was House Master of Friar’s Brook borstal. But, in life, he had not only been a serving police officer at the same time as Tony Cartwright, but he had died right alongside him on that awful night when Gould’s garage went up in flames.

‘Mr McClintock?’ Annie asked. ‘The House Master from Friar’s Brook borstal? I’d remember if I’d seen his name anywhere.’

‘No mention at all? That’s strange. Or maybe it’s not strange at all, given the way names come and go so freely in those files.’

‘This much I know, Sam – PC Cartwright died and his death was covered up,’ Annie said, her voice tight and constrained. ‘And the main culprit for that cover-up was DCI Michael Carroll.’

‘Well, at least we know exactly where he is and what he’s up to right now,’ said Sam. ‘Unlike your other suspect, DI Pat Walsh.’

‘And then there’s DS Ken Darby. We need to track them all down, Sam. We need to know exactly what happened, how they were involved, and why they covered it up.’

‘You need to know,’ Sam gently corrected her.

And now Annie looked up at him, her face drawn and pale, her eyes slightly bloodshot as if she had been crying.

‘Yes!’ she hissed at him. ‘I need to know. I need to know who I am and why all this is so damned important to me and what the hell’s going on!’

‘Shhh!’ Sam glanced over his shoulder at Chris and Ray, both of whom were pretending to do paperwork whilst in fact they were flagrantly ear-wigging. Drawing closer to Annie, Sam said in a low voice: ‘We need to talk.’

‘Well I don’t want to talk!’ Annie suddenly snapped at him. ‘I want to find out what’s going on and I want to do it my way!’

‘I did it myyyyy waaaaaaaayyyy!’ Chris suddenly bawled out.

Sam hurled a stapler at him. Chris shot him a threatening, dead-eyed, Yul Brynner look, and seemed ready to challenge him to ‘draw’ once again. Ignoring him, Sam turned back to Annie and urged her to keep it down.

Annie glared at him and said in a low voice: ‘I want to do it my way because I don’t like your way!’

‘What are you talking about?’

In the background, Chris was putting the hurled stapler back together again whilst burbling under his breath: ‘Regrets … I’ve had a few … like that curry after the film. Stone me, I’m regretting that!’

‘Your way, Sam, is all about keeping things from me, and not telling me what you know,’ Annie hissed. ‘You’ve known things … about me, about … about everything! But you haven’t said.’

‘Annie, keep it down, this isn’t the time or the place.’

‘How can I trust what you say, Sam? You’ve kept secrets from me! You knew things – important things – but you didn’t tell me!’

There was a deep, chesty rumble, and the sound of congealed phlegm being grunted out. Gene Hunt strode into CID, a fag smouldering in his gob.

‘Morning, my lovelies,’ he intoned.

‘Draw!’ Chris challenged him, squaring up for a gun fight. ‘I said, Guv.’

Gene stopped dead in his tracks, looked Chris over like he was made of freshly dropped shit, and then said in low and menacing voice: ‘If that’s Brynner from that bloody kiddies’ flick you’re doing, Skelton, then I’m giving you precisely one second to pack it in.’

Chris responded by drawing his imaginary revolver and pow-pow-powing the Guv with it.

Gene turned down the sides of his mouth in a fish-faced grimace of utter disgust and declared: ‘Brynner ain’t no cowboy! He talks like bloody Brezhnev and looks like a squeezed dick with a Chinky’s face painted on the bell.’

Looking suddenly deflated, Chris said meekly: ‘I … I thought you liked Westerns, Guv.’

‘Westerns, Chris! Westerns! That abortion showing in the flea pits out there ain’t fit to wipe the arse of a decent Western! You think John Ford would crank out some shite about wind-up toys getting porked by stockbrokers in a theme park?’

Ray’s ears pricked up at that: ‘Oh aye? I didn’t know there was porking in it. Do you get to see much?’

‘You see a bit,’ Chris said, turning to Ray. ‘There’s this bird, right, and she’s a robot-like but you wouldn’t know it, it’s not like her tits are made out of foil or nuthin’, but her eyes do go a bit silver at one point. Anyway, this scrawny fella with a ’tache is getting the right horn with her, so he …’

‘I’ll have no more talk about Westworld in my department!’ Gene bellowed. ‘Yul Brynner ain’t no cowboy – end of. John Wayne! Randolph Scott! Saint Gary of Cooper! Them’s cowboys, Christopher, them’s bloody cowboys, not that slappy-skulled Ruskie mincing about with two Evereadies up his arse and a scrote-sack full of fuses! Robots?! In Stetsons? I’ve shit ’em!’

He stomped furiously to his office, flung open the door, and disappeared inside. A moment later, his voice roared out: ‘Tyler! Cartwright! You are summoned!’

Without a glance at Sam, Annie got to her feet and strode briskly towards the Guv’s office. Sam sighed and followed her.

They found Gene prowling about, agitated and enraged.

‘Bloody robots …’ he growled. ‘Bald bloody robots, with slitty eyes. Oh, how our days have darkened, Tyler, how they have darkened!’

Gene glanced round at Sam and Annie, swallowed down his indignation at the state of seventies cinema, and plonked himself heavily into his chair. He planted his feet up onto his desk.

‘Right, enough of that, I’ve got a city to police,’ he said, appraising them both critically. ‘I take it, Cartwright, that in relation to your behaviour the other day DI Tyler has dished out a suitable bollocking – or whatever the female equivalent is … a “fannying”, if that’s a word. Well? Has he?’

‘Yes, Guv,’ Annie muttered.

‘And have the pertinent lessons been absorbed?’

‘Yes, Guv.’

‘You could at least pretend to sound like you give a toss, Cartwright.’

‘Yes, Guv.’

‘Okay then. I’ll say no more about it. But what I do want to discuss is what you’re up to.’

‘Guv?’ Sam and Annie asked in unison.

‘WPC Knicker-Elastic has been conducting some sort of private investigation,’ Gene clarified. ‘I want to know what it’s about, and I want to know right now.’ He waited for an answer, and when he got none he raised an eyebrow and said: ‘Well?’

‘It’s not easy to explain,’ Sam suggested.

‘Then let dopey-tits have a go.’ Gene narrowed his eyes and stared at Annie. ‘Come on, ducks, I’m a busy man. What are you up to with all them old police files?’

‘It’s … personal, Guv,’ said Annie.

‘Oh, cobblers it is!’ Gene suddenly barked at her, sweeping his feet from the desk and looming up out of his chair. ‘What’s “personal” in this place? We’re coppers, you drippy mare! All of us – even you! So start behaving like one!’

‘Oh aye?’ Annie shot back at him. ‘By banging on about some stupid cowboy film?’

‘Yul Brynner ain’t no cowboy!’ Gene bellowed. ‘And don’t try and change the subject. What’s in them files, eh? What are you after? And what about these ex-coppers on that list of yours? Have you been knocking on their doors asking for a chat?’

To Sam’s utter amazement, Annie simply turned on her heel, strode out, and slammed Gene’s officer door behind her.

For a few heartbeats, Gene watched the empty space where Annie had been standing, then he turned the full force of his gaze into Sam. Silently, he waited for an explanation.

‘She’s upset, Guv,’ Sam said.

‘So am I. Bloody robots!’ And then, looking intently at Sam, he added: ‘What’s going on with her, eh? Why’s she got the hump like this?’

Sam ran a hand through his hair. Damn it, this was a tight corner. How the hell could he explain?

Gene sank slowly into his chair, placed his hands carefully upon his desk, and drummed his fingers. Without warning, he suddenly stopped. Whatever thought process had been going through his head was evidently completed. The Gene Hunt mind had cogitated – and now it was made up.

‘She don’t belong here, Tyler,’ he said. ‘She ain’t made of the right stuff. Take her off my hands, will you.’

‘Take her off your hands?’

‘Give her something else to do. Dick her senseless. Marry her, if you can face the prospect. Stick her in the kitchen. Get her pushin’ a pram. Sell her to a brothel and piss the proceeds up a wall. Frankly, I don’t give a wet fart in the deep end of the swimming pool what becomes of her, just so long as she’s not cluttering up my nice, clean shiny department no more.’

‘Guv? What are you saying?’

‘I’m reviewing her suitability as a copper.’

Sam took a step forward: ‘You can’t do that, Guv.’

‘On reflection, Tyler, I think you’ll find I can.’

‘Just because she honked your stupid horn and walked out in a huff?!’

‘There is nowt stupid about my bloody horn!’ Gene bellowed. And then, calming down, he leant back in his chair and said: ‘I ain’t made a final decision yet. The ball is still in play. But if I get wind of any further abuses of police records, or conducting interviews without my say-so – or if she so much as glances at my horn – I will have her suspended and investigated. She can lose her job. She can go to prison.’

‘Oh, don’t be so stupid!’ Sam scoffed.

‘Gross misuse of official police records! Using her standing as a police officer to conduct private affairs! That ain’t just a slap on the wrist, Sammy boy, that’s the full disciplinary. Now – I think you’d better go out there and get them files off her. Put ’em all back on the shelves where they belong and forget all about them. Tell her to chuck that list of ex-coppers in the bin. And get her doing something useful round here, like dusting that plant with the big leaves outside the canteen – have you seen it? It’s a state.’

Sam threw up his hands: ‘You’re mad, Guv! Annie’s one of the best coppers you’ve got! And you’re going to flush her and her career and her life down the pan just because …’ He broke off, furrowing his brow, thinking hard. Almost to himself he said: ‘Wait a second …’

‘Don’t bother trying to change my mind on this, Tyler. Cartwright’s been a disruption in this department from day one. Her recent behaviour’s just the final straw.’

‘Wait, wait, wait a second,’ said Sam, realization dawning on him. ‘This isn’t just about Annie’s behaviour. It’s about what you’re frightened she’s going to dig up in those files!’

Gene stared at him, unblinking, fierce. In a menacing voice, he said: ‘There are dogs out there, Tyler. Big ones. Big, bastard ones with bad teeth, bad breath, and bad manners. And right now this very moment, them big, bad bastard dogs are fast asleep and dreaming of bunny rabbits – and whilst they’re asleep, so are all their grubby secrets, you see?’

‘You know there’s a cover-up in those files, Gene,’ said Sam, looking him straight in the eye.

‘Of course there’s a cover-up in them files,’ Gene answered in a low voice. ‘Hundreds of ’em. This is CID, what do you ruddy expect? But whatever Cartwright’s digging up is ancient history. It’s done with. So let’s leave them big, bad doggies snoozing, yes? Coz if some ’erbert steps on the wrong tail and wakes one of ’em up, then somebody somewhere’s gonna get bit. ’Orribly. Where it ’urts.’

‘Those sleeping dogs,’ Sam said, meeting Gene’s gaze. ‘One of them isn’t you by any chance, is it?’

Gene leapt to his feet and slammed his hands down on his desk. And then, with effort, he got control of his temper.

‘I’m ruddy Snow White compared to some,’ he breathed, shaking with rage.

And Sam could see that he meant it. He could also see that the Guv knew, or guessed at, some of the skeletons in CID’s cupboards. Perhaps he had some inkling about what went on back in the sixties, when Clive Gould had half the coppers in this place safely on his payroll.

The more Annie picks through those files, the further she walks out into a minefield – and Gene knows it, Sam thought. Maybe the Guv’s more concerned for her safety than he can bring himself to let on.

Not wanting to rile Gene up any further, Sam took a breath, pitched his voice low and level, and said: ‘I’ve heard what you had to say, Guv, and I’ve fully taken it on board. Leave it with me. I’ll see that everything’s taken care of.’

Gene glowered at him for a moment, then slowly sank down into his chair. The tension in the room eased – but only slightly.

‘Make sure you do take care of everything, Tyler,’ he said. And with that, he dismissed his DI with an imperious wave of the hand. He had things to get on with. The racing pages didn’t read themselves.

CHAPTER FIVE: GARY COOPER (#ulink_208cb0dd-6b9f-5461-b06b-757e32c8b011)

Long after the sun had gone down, and a cold night had settled over the city, Sam found himself drawn back to the church where Michael Carroll was still holed up with his hostages. The police laying siege to the place were bored, sitting in their patrol cars or pacing around, smoking. The lights inside the church were on, visible in the coloured glass of the stained windows, but apart from that there was no hint of life.

Sam flashed his CID badge and strode past the coppers, stopping at the edge of the churchyard. He felt a powerful compulsion to go up to the door, go inside, and confront Michael Carroll, and not just in order to break the siege. Sam wanted to know what Carroll had seen, what form Clive Gould had taken when he turned up, and what – if anything – Gould had said. His own future, and Annie’s too, were bound up with the events going on inside that church, with the mysterious fate of Pat Walsh, and the horrors that Michael Carroll had witnessed at first hand. Sam had to speak to him.

It was taking one hell of a risk to walk up to that door. Carroll had been half out of his mind when he’d first gone bursting in there – what state would he be in now? Would he be delirious from lack of sleep? Paranoid? Psychotic? At the first sight of Sam, would he start opening fire on the hostages like he’d threatened?

I’m risking a blood bath if I go in there … and yet, I can’t stay away. I need to speak to him.

Sam hesitated, nerving himself to move forward – and then heard a noise from behind him. The uniformed coppers were challenging a man who had drawn too close, telling him to move back behind the police cordon.

Glancing round, Sam recognised him at once.

‘It’s all right, I know that man,’ Sam announced, striding over to him. ‘And I believe he knows me.’

McClintock did not look at all surprised to see him. The House Master was dressed very soberly, in a dark coat worn over a dark suit, with a dark tie knotted tightly at its crisp white collar. And yet, in a way that Sam could not explain, McClintock just didn’t look right. He looked somehow depleted in civvies, like a demobbed officer. He was a man born to wear a uniform.

The two men – Sam and McClintock – stood looking at each other for a moment.

‘I know an absolutely revolting caf? just across the way,’ Sam said. ‘Would you care for a coffee?’

McClintock nodded slowly: ‘Aye, Detective Inspector Tyler, I would. And a wee chat too, if you could spare the time.’

They sat together in Joe’s Caff, Joe himself still frying eggs despite the late hour. The man seemed never to sleep.

Sam sipped a strong, bitter coffee. McClintock looked at the tepid brew in front of him, but never touched it. Up close, Sam could see just how severely starched his white shirt was. He wore his tie very tight, like a noose, and his collar was held in place with immaculate silver collar studs.

For some moments, neither of them spoke – until McClintock leant forward and said in a low voice:

‘I don’t know what brought me to that church. Something compelled me. And then, when I saw you, Detective Inspector, I felt not the slightest surprise.’

‘You can call me Sam.’

‘I’d rather not. I’ve never been comfortable with first names. It’s either what attracted me to a life in uniform, or else a symptom of too many years in that world.’

‘Very well, then, Mr McClintock,’ said Sam. There was something strangely endearing about this man’s need for formality. Perhaps it was the glimpse of vulnerability that it betrayed, the hint of the nervous little boy hiding in the heart of the man. ‘Our paths crossing here tonight – it’s no coincidence, is it.’

‘It’s no coincidence. Something drew us together before, in Friar’s Brook, and it has done so again this evening. I think we both understand each other.’

Sam hesitated, then said with care: ‘Understand each other how?’

‘This place we’ve found ourselves in,’ McClintock said, ‘it only appears to be 1973. But it isn’t. Not really. Is it.’

‘No. It’s not really 1973. It’s somewhere between Life and Death.’

‘Yes,’ McClintock nodded slowly. ‘A strange place. Betwixt two worlds. We’re nae the living nor the dead.’

Sam nodded, and said quietly: ‘It’s such a relief to speak to somebody who actually realises that.’

‘Yes. A relief for me too. It is a … burden to know such things. It is a source of great loneliness.’

‘When I first met you, in Mr Fellowes’s office in Friar’s Brook borstal – did you know then?’

McClintock shook his head: ‘No. Not then. I had forgotten I had a life before this one. But it all started coming back to me a little later.’

‘But why, Mr McClintock? Nobody else here remembers. Just me … and now you. Why?’

McClintock stared thoughtfully into his wretched coffee for a few moments before replying. When he spoke, it was with slow, measured words.

‘For a time, when first I arrived here, I could recall my past with clarity, just as you can, Detective Inspector. I remembered the fire that consumed me, I remembered the pain. Like you, I knew that I was dead – or leastways, I was something very much like being dead. But again, like you, though I had lost my old life I had at least gained a new job. I was no longer DS McClintock of Manchester CID, but House Master McClintock of Friar’s Brook borstal. A new post for a new existence.’

‘And what happened?’ Sam asked. ‘You could remember your past life at first ... but then?’