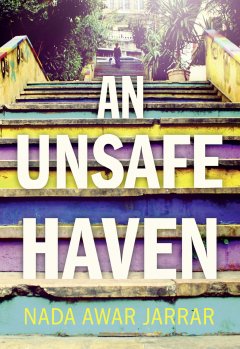

An Unsafe Haven

Àâòîð:Nada Jarrar

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:831.24 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 308

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 831.24 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

An Unsafe Haven

Nada Awar Jarrar

'Captivating …There's a breadth of humanity in An Unsafe Haven which is very moving. I loved the sense of Lebanon and of what is unique and precious about the Arab world' Helen DunmoreSet in contemporary Beirut, a rich, illuminating and deeply moving novel about a group of friends whose lives are shaped and affected daily by the war in Syria.Imagine trying to live a normal life in a world which changes daily and where nothing is certain …Hannah has deep roots in Beirut, the city of her birth and of her family. Her American husband, Peter, has certainty only in her. They thought that they were used to the upheavals in Lebanon, but as the war in neighbouring Syria enters its fifth year, the region’s increasingly fragile state begins to impact on their lives in wholly different ways.An incident in a busy street brings them into direct contact with a Syrian refugee and her son. As they work to reunite Fatima with her family, her story forces Hannah to face the crisis of the expanding refugee camps, and to question the very future of her homeland.And when their close friend Anas, an artist, arrives to open his exhibition, shocking news from his home in Damascus raises uncomfortable questions about his loyalty to his family and his country.Heartrending and beautifully written, An Unsafe Haven is a universal story of people whose lives are tested and transformed, as they wrestle with the anguish of war, displacement and loss, but also with the vital need for hope.

AN UNSAFE HAVEN

Nada Awar Jarrar

Copyright (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Nada Awar Jarrar asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover layout design: Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016. Cover photography © Mario Ramadan/EyeEm/Getty Images (steps) and Shutterstock.com (http://shutterstock.com/) (texture)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008165017

Ebook Edition ©July 2016 ISBN: 9780008165031

Version: 2016-06-01

Dedication (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

For Bassem,

With all my love.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u0571efe0-a27a-5a04-ba66-5c793df23cf1)

Title Page (#ubf278bd2-4e2b-5daa-9aab-5f6c71a7367f)

Copyright (#u982f6734-f621-57fc-bf43-2347d62750da)

Dedication (#ucac3292d-6799-5841-bac0-ca3d55204a36)

Chapter 1 (#u5a8bd607-572b-5722-a9b4-0c329199c345)

Chapter 2 (#u9b424929-9019-545d-9248-64eb7f9e52c2)

Chapter 3 (#ud9a07ffa-2630-50cf-876b-6e8428b66974)

Chapter 4 (#u97aeb2a4-97e6-58a2-8825-d888ec1c4215)

Chapter 5 (#ua5e5e8cf-35f7-5d37-a3f6-9b0ac07f865d)

Chapter 6 (#ua20b4be1-0d95-551f-a0d4-db19375b6ce8)

Chapter 7 (#u423c0969-47af-5940-9411-db114371fdd1)

Chapter 8 (#ue267d6c1-fca2-56a7-8b38-41c52ef95ead)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Nada Awar Jarrar (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

They are still on daylight saving and the light, soft and hesitant, comes early, through the gap in the curtains and on to the bed, shaping itself to the contours of their bodies, gently waking her.

Peter does not stir when she sits up. She looks at him, his features in repose beautiful to her, fair skin unblemished, his greying hair fine as silk, an implied calmness to his demeanour even in sleep that still moves her after so many years.

She gets out of bed carefully, puts on her dressing gown and looks back to make sure she has not disturbed him. In the kitchen, Anas is already sitting at the breakfast bar, hair ruffled, his eyes, when he looks up from behind his glasses, uncharacte?ristically flat.

—Anas, Hannah says quietly. You’re up early.

He does not respond.

She places her hand over his and feels a slight tremor in it.

—Is everything all right?

He squeezes his eyes shut and shakes his head. She puts an arm around his shoulder and, feeling him shudder, realizes that he is crying.

—Anas, please tell me what’s the matter. You’re scaring me.

He finally looks up at her.

—It’s Brigitte, he says in a whisper. She’s left Damascus and taken the children with her.

She lifts both hands to her mouth.

—I don’t understand, she exclaims. Where did they go? What happened?

There is a pause before he can reply.

—I telephoned them several times yesterday but no one was in. I’d been worried since that car bomb exploded in our neighbourhood after I left. I wanted to make sure they were all right, but when I called my mother late last night, thinking they might have gone there, she said they were gone.

—Gone?

A thought occurs to Hannah though she does not say it out loud. Please God they haven’t been kidnapped, she thinks. It is not unusual for people to go missing in Syria. Since the revolution and consequent civil war began, there have been tens of thousands of abductions.

—It’s not what you think. Anas has read her thoughts. Our neighbour downstairs saw the taxi we always use parked outside for them. They had lots of luggage. When my mother asked the driver later, he said he’d taken them to the airport.

—Thank God. She breathes a sigh of relief. Where do you think they went?

—I’m sure she went to her parents in Berlin. Where else would she go?

—So you’re going to call them?

He shakes his head.

—My in-laws moved recently and I don’t have their number. I didn’t think I’d ever need to get in touch with them without Brigitte there.

—At least you know they’re safe, Anas. Hannah is not sure what else she can say in the way of comfort.

—She waited until she knew I’d be coming here for the exhibition and left without saying anything about it. There is bitterness in his reply. She knows I would never have agreed to it.

—Brigitte has talked about leaving before?

He shrugs.

—Since the fighting began, whenever the subject came up. I always told her Damascus is home and I would not abandon it no matter what happened.

He waits for a moment until Hannah begins to feel a hint of his anguish.

—I also said I would never allow the children to leave. I reminded her that they would always be Arab.

—But, Anas, you can’t be surprised that she would want to get the children out of a country at war? Surely, you can’t.

—She doesn’t feel the way I do about Syria, he says. Why should she? After all, it’s not her country.

Hannah begins to ask him if he really believes any mother, regardless of her nationality, would not choose to remove her children from danger, no matter the cause, but decides to remain silent.

She sits down and feels a now familiar hopelessness rising through her chest, gloom that comes from her many years as a journalist writing about the affairs of a region constantly in turmoil. Silently, she gathers together the thoughts that she will later write down to use in the stories she is always working on.

In the past five years, the Arab world has swelled and raged as dictators have fallen and people in their hundreds of thousands have been killed and millions of others displaced. In Syria and in Iraq, in Egypt and Libya, and in the farther reaches of the Arab Gulf, we have looked on in horror while humanity appears to stumble over itself; and Lebanon, in the wake of all this turmoil, teeters on the brink. There are moments when it seems too big, too unfathomable and overwhelming a reality to take on, when I feel as if I – along with the region I once believed in – am moving through mud, fearful and hesitant, unable to take that next step towards release.

Living in Beirut can be deceptive; it offers a false impression of safety and permanence in the midst of all the upheaval. We feel the direct consequences of the tragic events in Syria, but it is hardly by choice. Is Brigitte wrong in distancing herself from what is going on? And are we, all of us, mistaken in standing by, believing ourselves helpless like this?

There is something else to be learned from the experience of this situation, something to do with the conflict’s essential incongruity, even to those of us who are closest to it. Nothing about brutal battles is acceptable, nor are they a normal function of human interaction. This is how people diverge in their perceptions. For the suicide bombers who have been striking in the heart of Beirut or Baghdad, in Benghazi or Sanaa, in heavily populated areas and at times of day when ordinary people are getting on with their lives and the highest number of casualties is likely to occur, for these extremists, there is no such thing as everyday life, nothing in their psyche that points to normality and recognition of the other as legitimate and worthy.

She sighs and places a hand on Anas’s arm.

—You’re in despair, I know, habibi, she says quietly. You have the sensitive soul of the artist that you are and are feeling overwhelmed right now. But things will work themselves out, you’ll see. We’ll find your family. I know we will.

*

During those foggy moments before complete wakefulness, Peter hears murmurings, imagines himself going outside in search of them, feet bare and his eyes, unbelieving, squinting in the breaking sunlight that bathes the furniture and floors.

It is only Hannah and Anas talking, he realizes.

Getting out of bed slowly, he stands still for a moment and listens further, the voices beyond gently rising and falling. He smiles to himself. It pleases him that his wife and good friend should get on so well.

When he joins the others in the kitchen a short time later, he is already showered and dressed.

—Morning, hayati, says Hannah. Sit down and let me pour you some coffee.

Peter looks at Anas but he has a hand over his eyes.

—Is everything all right? Peter asks. Anas, are you OK?

Hannah hands him his coffee and tells him what has happened.

He sits down and waits for his friend to look up. Anas is an extraordinarily handsome man. He has the brooding features characteristic of many Arabs, Peter believes, but in him they are softened by luminous eyes and a palpable quietness of spirit.

—How did she manage to get them out without your permission? Peter eventually asks. Surely they would have stopped her at the airport.

—If anyone did try to stop her, she would’ve paid them to keep quiet, Anas says. Anyway, they’re not too strict about things like that these days. Lots of people who have foreign passports and can afford it are leaving.

—At least we know they’re safe, Hannah interrupts the ensuing silence. Brigitte will get in touch soon, I’m sure.

—Do you have any idea where she might be? Peter persists.

—I’m pretty certain she’ll have gone to Germany to her parents. Still, it depends on whether or not she wants me to find her at this point. She’s got lots of friends to stay with.

Peter senses hesitation in Anas’s voice.

—We can try to find her.

Anas puts his cup down on the bar in front of him.

—I’d rather she got in touch first, he says. I don’t want to rush her. She’s probably confused and very angry with me right now.

—No matter how she feels, says Peter quietly, they are your children, Anas, and you have a right to know where they are.

A moment later, he wonders if this was the right thing to say to a man in such a vulnerable state. Perhaps empathy, rather than rational thinking, is what he needs right now.

Peter looks at Hannah but her expression tells him nothing. He sighs and lifts his cup to his mouth.

There are times when he harbours doubts about his true nature, wonders whether or not being a physician has made him impervious to the pain of others, or if, even with those to whom he is closest, he has developed a studied indifference, a metaphorical second skin that protects him from the dilemmas of compassion. Some of this disconnection, he knows, he brought with him from America and a childhood home where a show of emotions was discouraged. During periods of clarity, he has seen that, in trying hard over the years to adapt to a culture so different from his own, he has lost the ability to appreciate the subtle ups and downs of human relationships, a shortcoming he is reluctant to acknowledge openly but which nonetheless shapes his everyday dealings with others. Once or twice, when he has tried to approach Hannah with his suspicions, the fear that she might confirm them and judge him further for his apparent indifference has stopped him. At times distrustful of his feelings, he has become adept at avoiding them, working too-long hours to pay proper attention to anything else or simply putting on a fa?ade of detachment that leaves him only in sleep.

As the situation in Lebanon has worsened and Hannah’s anxieties continue to increase, he has been close, at times, to admitting a distance even from her, a pulling away from the concentrated passions she harbours, which are a good portion of her essential self. And although he is troubled by Anas’s sadness now, he is inclined to leave the dealing with it to Hannah, for whom extreme emotions are an everyday occurrence.

It is often like this, he thinks, my true self appears to me only in bits and pieces, like flashbacks in a film, incoherent but sharp-edged, revealing as much as they manage to hide from me. That surely is why I am bewildered at times like these.

He looks over at his wife again before continuing.

—Look, Anas, I have a friend who is with the International Red Cross here. Maysoun is Iraqi and works mostly with refugees from there, but I’m sure she can find out for us. She told me they have a register of people fleeing war. She’d be able to trace anyone who has left Syria. What do you think?

—I don’t suppose it would do any harm to find out, Hannah says, looking at Anas. Let Peter do this and then we can figure out where to go from there.

Anas smiles.

—You are good friends, he says. Once the exhibition opens and I can go back to Damascus, I’ll be able to think more clearly and decide what to do …

—Wait a minute, Peter interrupts him. You don’t have a German passport, do you?

Anas shakes his head.

—I’m pretty sure the embassy in Damascus will have closed down. If you decide you want to go to Germany to find your family, you’ll have to get your visa from the embassy here.

—He’s right, says Hannah. You can’t possibly think of going in and out of Syria just yet. Besides, there have been battles going on very near Damascus the last few days and it’s dangerous. Stay on with us for a while longer, until we can work out what to do.

Anas hangs his head. Peter looks on as Hannah puts her arms around him and, for a brief moment, is conscious of the rhythmic beating of his own heart.

When Anas goes inside to get ready to leave for the gallery, Peter turns to Hannah.

—I can’t believe Brigitte would leave like that without telling Anas about it, he says.

—Maybe she was worried he’d use the children as an excuse and prevent her from leaving. He could have contacted the authorities and had them stopped at the airport. She wouldn’t have been allowed to take the children away without his consent.

—I can understand her wanting to save the children from the war, Hannah. But she should have found a way to let him know she was planning to escape. She could even have come here with the children instead of disappearing like that.

He grabs his jacket and starts for the front door.

—By the way – he turns to ask her – are you visiting another refugee encampment for your articles today?

Hannah shakes her head.

—I can’t do any work after what has happened. Anas is absolutely devastated and I need to be with him.

—I realize he’s upset. But nothing we do at this point is going to make him feel better.

She looks at him with what seems like reproach.

—He can’t be left to deal with this on his own, Peter.

—Anas is going to feel upset no matter what we try to do. He has to cope with the situation in his own way and he’s aware we’re here to help whenever he needs it.

—Whatever you might think, I will not leave him today. I have to make sure he’s OK. Then, frowning, she continues quietly: You know, there are times when we seem so different, you and I.

Before he can be alarmed by what she has said, he decides to make a joke of it.

—Just as well we are and I can help tone down your angst, he says.

But she only turns away.

Chapter 2 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

From the beautiful residential neighbourhood of Abou Roummaneh in Damascus, Anas drives his children to school every morning, stopping the car to let them safely out, then placing their bags on their backs and watching them walk away, his heart leaving with them, the tug of separation lingering as he drives on to his studio on the outskirts of the city, as he sets to work and anticipates release from the everyday, as he dreams.

With Marwan and Rana, he has tried to cultivate a quietness that had been largely absent in his own childhood, in which his parents’ love had been too intense at times, too enveloping to allow him breath. Growing up, he had had the comfort of knowing that whatever the challenges, whether it was anxiety over schoolwork or rejection by friends, whether he got disapproval from strangers or simply felt disconnected from the world around him, whatever the break these experiences caused inside him, there would always be someone or something to put him together again. His mother making his favourite sweets and the pleasure in her eyes as she watched him eat them; his sisters, both older, helping him with homework, often doing it for him while he went out to play; his father insisting, at the end of the school week, that he walk down with him to the old souk to help with the shopping. Once there, Anas became so engrossed in the surrounding activity and displays, felt so much a part of them, that he forgot his troubles.

Yet he had felt stifled by this closeness at times, and recalled occasional moments of aloneness that stood out as bright and exceptional: the sun on his back as he bent down on the terrace to play, undisturbed, with a new toy, the joy in that anticipation, or at night, a little while before sleep, shutting his bedroom door and sensing in this instantaneous, temporary solitude the opportunity to be utterly himself, feeling the relief in that, the release. He has always understood that it is exactly this ability to disengage, with fluidity and without notice or regret, that makes way for the artist in him, that defines his deepest being.

He remembers the joy his parents had felt when in his final year at school he passed his baccalaureate exams with distinction, the pride and the boasting, their expressions of hope for his future – medicine perhaps, or law, they advised him –and then their disappointment when he had refused, their despair that he would be willing to give up the opportunity to elevate his standing and that of his family in a watchful and highly critical society. But the urge in him to create, to portray in shape and in colour what defined his essential being was too strong to ignore, and for several years, during which Anas and his parents hardly communicated, he had taken on menial jobs that allowed him to pay for occasional art classes and materials, until the day he was able to announce to them that he had won a scholarship to study art in Germany and their resolve was finally broken.

Anas is aware that in defying his parents’ plans for him as the only son in a traditional Arab family, he became stronger and more determined to succeed as an artist. But this is not a fight he wants to engage in with his children, not the path towards fulfilment that he wishes for them. He sees instead a flexibility in their outlook that they have gained from their mother; this pleases but also at times frustrates him. It is a mirror he is not always willing to look into.

He works on the top floor of an ageing three-storey building, once the pride of Syrian design, with an open stairwell that looks on to a garden overgrown with plants and a small pond that is long dry; and standing right outside his front door, growing in a huge, ancient pot, is a beautiful jasmine bush that dies gracefully in winter and in spring fills the evenings with its perfume. Inside the spacious, high-ceilinged rooms of the apartment are the light and shadows he has always sought, a weightless glowing, and at its edges, a muted gloom, the suggestion of colour that serves as his inspiration.

He spends the best hours of his day sitting at a wooden table placed directly beneath a large, open window, painting with colours he has painstakingly blended together or sculpting materials which he manipulates with nervous hands, slowly but surely drawing the outlines of his better self, he knows, the man he sees clearly in his mind’s eye but who in lesser moments appears dulled and ordinary.

Anas has finally found the recognition that a handful of Syrian and Iraqi artists now enjoy thanks to a greater interest in their work around the world, a recognition that is deserved. However, he comforts himself with the thought that increased material comforts and growing demand for his pieces have neither influenced his outlook nor made him change his work habits. He prides himself on that, trusting that his instincts will continue to carry him through what might turn out to be only a temporary rise. He knows that art is the one thing, above all else, that gives him life.

But if his work has achieved success, his personal life – more specifically his relationship with his wife – has not fared well. That too is a long story which he cannot bring himself to talk about, even to his closest friends.

He had been at art school for almost a year when he met Brigitte at a gathering in the home of a mutual friend. She was tall and attractive, like many of the women he had met since his arrival in Germany, and fair: a striking contrast to his own colouring that appealed to him. Yet he had sensed something about her from the first: a willingness and humility he admired; an interest, too, in him that went beyond that initial attraction. Their affair had been passionate and serious in a way that was unfamiliar to him, demanded from him wisdom that his upbringing and consequent experience had not prepared him for, a view of relationships, of women, that was new and challenging. They had joked once about their closest moments being as lessons in love, with Brigitte as the teacher and he the willing student.

When they married not long after meeting, she had told him she looked on the prospect of moving to Damascus to live and raise a family as a welcome adventure. If she loved her husband so much, she admitted, it was in large part because she was fascinated with his culture, longed to discover a world far outside her own European upbringing.

Syria had lived up to all her expectations at first, as an authentic Arab country that remained largely faithful to its heritage, perhaps – and the irony of this did not escape her – because it had lived so long under dictatorship that Western influences were few and far between. Anas had been charmed, in those first few months after their arrival, by his wife’s wonder at the peculiarities of life in Damascus, at its manifestations of old-world sophistication alongside an innocence that he could see moved her greatly.

Once, using a cashpoint at one of the bigger banks in the city, Brigitte had at first been alarmed when a small group of what were clearly labourers came to stand beside her, apparently watching what she was doing. When Anas explained in German that the service was very new to Damascus and that the onlookers were merely curious, she had smiled and gestured to them to come closer and asked Anas to translate as she gently explained exactly how the machine worked. What she had not known, what Anas did not have the heart to tell her at that moment, was that the men were unlikely ever to need the services of an ATM since bank accounts were a privilege that only a wealthy few enjoyed.

She marvelled also at the daily proximity of people one to the other, the houses in the old neighbourhoods attached to one another in rows, their walls porous, voices and emotions filtering through them in the breathing air, people moving through the crowded alleyways that represented streets, bodies touching as if in a shared dance, the spaces above them filled also with anticipation, and everywhere, at tables eating, in rooms punctuated by conversation, by deathbeds and in silent prayer, the presence of an unseen but nonetheless all-powerful notion of God.

She told him, in those early days when they talked about their almost daily excursions into the heart of the city, that she had never known such clear evidence of vitality, of the feeling that she could, whenever she wished, dip her heart into it and come out overflowing, of the certainty that in loving and being with him, she had finally found her way home.

And if he were to be truthful with himself now, he would have to admit to his wife’s influence on his view of their relationship, the honesty with which she insisted they communicate, the transparency in their dealings with each other.

But neither of them had reckoned on the difficulties Brigitte would eventually encounter in trying to fit in with Anas’s family. His mother, he knew, had been devastated at the news that he would be returning from five years studying abroad with a foreign wife and did not hesitate to show her disapproval at every opportunity. And while his father and sisters tried to make Brigitte feel at home, there was no question as to their disappointment in his choice.

His family’s feelings about his young wife, he was certain, were not personal. Had she been merely a girlfriend who would later return to her own country, they would have found her delightful, would have welcomed her with open arms; but marriage being, to their minds, a lifetime’s commitment, they could not see her playing that long-term role with the dedication to social convention that it deserved; worse still, they could not see themselves settling comfortably with the thought of it.

Anas had been confident that once grandchildren came along the conflict would naturally resolve itself, but the birth of his son and daughter served only to complicate matters further. Brigitte mistakenly believed that she and Anas would be exclusively in charge of their children’s upbringing; she had not reckoned on the role of the extended family in Arab culture and arguments had ensued between them as a result. It began over little things like the grandparents feeding the children sweets their mother insisted were not good for them, or ignoring her instructions about meal and bedtimes when the children stayed with them, and eventually escalated into a headlong battle over who exactly was in charge.

Disagreements became especially heated over the influence of the family over the boy, Marwan, who was generally considered more important because he would eventually carry the family name.

Anas remembers especially one Sunday lunchtime when, as was their custom, they had all gone to his parents’ house. Once lunch was over, Brigitte had asked Marwan and Rana to help with the clearing up but Anas’s mother had been horrified when she saw her grandchildren at the kitchen sink washing dishes, had ripped the apron from around Marwan’s waist and pushed him away.

Anas had been surprised to find himself taking his mother’s side even though he was aware that Brigitte would find this unforgivable.

—How could you let her do that, Anas? Brigitte had begun. Is this how you want our son to be brought up? To think of himself as superior to women and believe they should be relegated to menial tasks?

—That’s not what I want at all, Brigitte, and that’s not what my mother meant. She’s an old woman and she’s set in her ways. Why won’t you give her the benefit of the doubt?

—Your mother effectively told Marwan he was better than his sister, that it was all right for her to do the dishes but not for him. How do you think that made Rana feel? Are her feelings less important because she’s a girl?

—When have I ever acted as if Marwan was more important? You know that’s not how I feel, Brigitte, so stop accusing me like this. Haven’t you learned anything about our culture in the years you’ve lived here? Or is it just that you think your Western ways are better?

—Western or not, Brigitte said, what happened was not right and you know it.

She took a deep breath before continuing.

—What’s happened to us, Anas? Why don’t we talk like we used to? You’ve changed so much recently that I feel I can no longer get through to you.

At these words he had been conscious of a resentment towards his wife’s foreignness that he feared he might never shake off.

—Do you mean get through to me or get me to think and do what you want? he retorted. You refuse to get on with my family and you are constantly trying to turn my children into something they are not. My children are Arab and this is their culture. When are you going to accept that?

If Anas is not able to ascertain exactly how the trouble between them had started, then he is honest enough to admit to himself that his own behaviour after that Sunday had done little to minimize it. With the growing pressure of work, he began to spend less time at home, travelled a great deal, was secretly relieved at the opportunity to avoid conflict, and left Brigitte to cope on her own. But she had not coped, he realizes now; she had become more isolated than ever, until the day the war in Syria began and all she could talk about was leaving. He had tried to make her see the conflict as he then perceived it: a challenge the country would have to go through before it could move forward, a disintegration that would eventually lead to renewal. Brigitte accused him of naivety, of being unwilling to admit to himself that with the escalation of violence, the conflict was headed towards disaster, had even told him once that he was willing to endanger the lives of his own children to maintain the illusion of Syria as home. His intransigence on that point, his insistence that they remain in Damascus, had driven them even further apart. Other matters came to light for him – and no doubt for her as well – as to the extent of their differences, matters which had not been personal at first but which eventually became so significant that they threatened to compromise their love for each other. It was clear that, faced with difficult circumstances, their backgrounds had led them to contemplate different solutions. For Anas, staying on in Damascus was not only a demonstration of his solidarity for his country but also an act that would serve to reinforce its existence, make it somehow resistant to break-up, while Brigitte maintained that a nation was not defined by its borders but by the unity and common vision of its people.

Thinking of his predicament now, despite the anger and frustration he feels at what Brigitte has done, it is almost impossible for him to imagine a life without her, though he admits to himself that there have been moments when he has hoped for just that, when he has sensed the probable inner peace that different life decisions might have afforded him. Where and at what juncture could I have done things differently? he asks himself.

There is great release for him in art; even now, at the news of his family’s departure, his first instinct is to go to the gallery where an exhibition is to be held of his work and spend the day there, among the canvases and away from worry. He is grateful for the support of his friends but for the moment, he knows, there is only one place for him to be.

Chapter 3 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

Hannah walks with Anas to the gallery in Beirut’s downtown where his exhibition will be held. On their way, they stop and sit on a bench on the Corniche, admiring the beauty of the Mediterranean, which, on this cool, sunny day, is smooth and deeply blue.

—I could never live anywhere but by the sea, Hannah says.

—This particular one, you mean?

—Probably, yes. You see how quiet and silky the water is now? Don’t be deceived by it, though.

—Huh?

—I mean, Hannah continues, during thunderstorms, the waves are massive. It’s impossible to walk here then because you’d be swept out to sea.

—Have you ever imagined living anywhere else besides Beirut? Anas asks after a pause.

—Well, we lived in Cyprus for a while during the war …

—Yes, I know. I meant now, when you can make the choice.

She sighs.

—I know many people who have the means and the opportunity are choosing to leave right now, but where would we go? Work is good here and I don’t know that we would want to start all over again anywhere else.

—You get satisfaction from your work, Hannah, but the same can’t be said for Peter.

—What do you mean?

—We were talking about it only the other day, Anas continues. He’s stuck in an administrative job he doesn’t enjoy and I think he misses being a doctor.

Hannah turns to him.

—He hasn’t said anything like that to me. Surely he would tell me if he really feels like that.

—Maybe he’s not sure how to approach it. After all, if he weren’t living here, he would be able to practise medicine.

—I didn’t ask him to come, Anas, she says impatiently. He wanted to be here.

—He wanted to be with you and you insisted on staying in Beirut.

She shakes her head and looks out over the water again.

—But that’s not what I meant to talk about, Anas says. I was asking you if things got worse and some kind of civil war breaks out again, would you be willing to leave Lebanon? It’s a possibility, you know, that our conflict will spill over into this country.

—A possibility? A war of attrition is already going on in Tripoli in the north and in the Bekaa, in the towns bordering Syria. It could all spiral out of control, I agree.

But Anas persists.

—You haven’t really answered my question, Hannah. What if you had children. Would that make you think differently?

She shrugs.

—I suppose we’d have to think about it seriously then, she replies. I suppose we would be concerned about their safety … Then something lights up in her head. Oh, you’re asking me if I approve of what Brigitte has done, aren’t you?

—Do you think she did the right thing?

Hannah realizes that she’s treading on dangerous ground here.

—I don’t think she should have made the decision on her own and then left without telling you. But I can perfectly understand her wanting to take the children somewhere safe.

She puts a hand on his arm to reassure him.

He gets up and she follows.

—What if she never gets in touch? he asks her. What will I do then?

—Why would you say that, Anas? What makes you think that? Brigitte wouldn’t do anything to deliberately hurt you. I know she wouldn’t.

He moves ahead of her and Hannah, trying to catch up, trips and almost falls over.

—Anas, please wait. What’s really going on here?

He stops and turns to her.

—The truth is, Hannah, the truth is things haven’t been going well between us for some time now. I think she’s left me for good.

They fall silent and Hannah wonders, not for the first time, how much longer they will have to endure the repercussions of years of war on their relationships, their family ties.

In 1982, as invading Israeli troops were closing in on Beirut, our family was evacuated on a ship taking Westerners out of Lebanon. My father used his connections with one of the embassies to get my mother, my brother and myself on board the ship. Throughout the journey to the island of Cyprus, the sea surging beneath us, Mother had clung to me and Sammy and cried. I was ten years old and felt a finality in that grief, a suggestion of relief that scared me. How can we possibly leave home? I wondered. Will we ever be able to return, and without Father, are we still a family? These questions, that initial dread, have never left me.

We spent, along with thousands of Lebanese like ourselves, a number of years on the island, during which we lived in a small apartment near the school that my brother and I attended. I remember that time as an interlude between real life in Lebanon before the war and life there once the conflict ended, mimicking my parents’ attitude towards this displacement as a period of anticipation regardless how long or how damaging the waiting to return might be. Whenever there was a temporary lull in the civil war and speculation mounted that the conflict was over, Father would decide we should return home and we would prepare to uproot ourselves, only to be told, days or weeks later, that it may be a little longer before we could pick up from where we had left off what seemed a lifetime ago. Even the friendships that I managed to make during this hiatus had hesitation in them; they predicted their ending even as they began, sacrificing the promise I might have derived from them had they endured. It was not until fifteen years after the conflict in Lebanon began that the warring factions finally signed an agreement that ended the fighting and we were able to return and be a family again.

But coming back had not been as easy as we thought it would be. Beirut had changed almost beyond recognition, not just in terms of the physical destruction everywhere but in the attitude of the people too, those who had stayed behind and harboured resentment against others who were lucky enough to escape the worst of the fighting. The friends I had hoped to meet again had either left for good or were reluctant to renew their relationships with returnees like myself.

When I began attending classes at the American University of Beirut, I felt like an outsider; the bonds I thought I had with my country, its culture and history were tenuous at best, non-existent for the most part. What I remembered of home had been irreparably destroyed by present reality, seemed only to have survived as sentiment in the minds of exiles. Eventually, my brother Sammy decided he could not live with all these changes and left for America where he studied and eventually settled down with a family of his own.

My career in journalism began soon after I graduated when I went to work for an international news agency, first as a fixer for the foreign journalists who came to Beirut to cover stories on the region, and then as a reporter. It was not long after Mother fell ill and died that I met and married Peter and, in growing older, began to believe I had gained some wisdom.

Since the war in Syria began nearly five years ago, it seems there is no end to the misery it can cause. Those who flee it and seek refuge in Lebanon bring their heartache with them, and for nearly four years now, Beirut’s street corners have been manned by insistent beggars by day, and at night, in shop doorways, under bridges, in abandoned buildings and anywhere a nook can be found, there are sleeping figures, whole families, wrapped in whatever they can find to shield their eyes from the light. Many others have fled to Turkey and Jordan, countries that also have borders with Syria. Most recently, hundreds of thousands of refugees have been making the perilous journey to Greece and France, to Croatia, Hungary and Slovenia, and on to Austria and Germany and still further north, in search of safety and welcome.

Things are not as they should be. There is pain where there should be strength, hesitation instead of resolve, and in the places where imagination once had free rein, the Arab people are tied to the foundations of their fears.

By the time they arrive at the gallery, Anas has told Hannah about the problems he and Brigitte have been having and she has voiced the necessary commiserations: I didn’t know; I’m so sorry; maybe it’s not as bad as you think; and, finally, what can I do to help? She eventually realizes that it is not solutions he is asking for but the simple relief that telling her affords him.

The gallery is smaller than she imagined it would be but there is plenty of light and the carpets and other surfaces are immaculately clean. Some paintings have already been hung while others remain on the floor, propped up against the walls; and sculptures, mostly small to medium-sized pieces, many of which are still swathed in bubble wrap, have been put on stands that are placed at intervals in the centre of the room.

—Do you like it? Anas asks.

—Yes, it’s lovely and welcoming.

—That’s exactly the feel I wanted for this exhibition. I wanted it to feel intimate.

—Is it OK if I take a look around? she asks.

—Yes, of course. I’ll have to get to work on the lighting, anyway.

Hannah watches him walk into the office at one corner of the gallery and turns to explore on her own.

She has always loved Anas’s work, the suggestion that it offers more than the eye can see about the circumstances in which it was conceived and executed. The pieces are mostly sombre, the colours he uses muted and unassuming, yet there is something about the square-headed figures he depicts, their limbs out of proportion to their torsos, their features fragmented and eyes usually closed, that moves her. They do not inspire joy, she thinks, but rather compel her to think about the politics of a country that has lived under dictatorship for decades and, in trying to break free, has now lost its way.

She takes a closer look at the pieces within reach and realizes that what fascinates her most in contemplating artistic works is the process itself, the ideas and people that inspire creativity, the phase during which a piece is brought into being by its creator and that moment when the artist instinctively knows that a piece has achieved completeness.

Among these objects of poignant beauty, she also experiences a sense of release, an interval of peace that dispels her misgivings and allows her, momentarily, to dream.

Chapter 4 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

In the Baghdad of her childhood, in the dazzling summer heat, Maysoun would run out to the back garden, her feet kicking dust in the yellowing grass, and play in the shade of her mother’s beloved naranj trees, fragrant and laden with fruit. The exact nature of the games she played now eludes her but she recalls their joys with unwavering clarity: the embrace of silence in those seemingly undying hours and a conviction in her young heart that life was unchanging, that love would always be to hand.

She remembers other moments too: her father’s voice calling to her to come in out of the sun; the welcome feel of cold water splashing on to her burning face; and, early in the evening, climbing up to the roof with her mother to unfurl the mattresses on which the family would sleep to escape the stifling heat trapped indoors, the marvel of darkness descending, the anticipation.

Later, lying with the dark sky above and familiar, still bodies breathing beside her, Maysoun would listen again for confirmation of that earlier happiness and receive it in the clamouring abundance of stars or in the whispers of neighbours carried across rooftops by the night breeze: memories of Baghdad that would last forever.

An only child, she was born to older parents who had until then settled themselves into the relative comfort of childlessness but who nonetheless welcomed the disruption to their lives that followed her coming. They had loved her with something like indecisiveness at first, but with time and growing confidence in their own roles their affection for her had become more sure so that instead of freeing her as she grew, they tethered her further to the notions of childhood and dependence that she had hoped to leave behind, the idea that in the realization of need is borne the willingness to love and to give.

In adolescence, at a private school for girls, Maysoun discovered the kind of freedom others enjoyed, classmates with European mothers from countries of which she had never heard and which she imagined more exotic than her own – Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, Norway and Denmark – tall, attractive girls who dressed daringly and expressed contempt for their elders with ease. In admiring and eventually emulating them, she was nonetheless aware of the necessary impermanence of these friendships, for she was conscious of her differentness, of the essential truth that while these young women rebelled with a view to their futures outside Iraq, she would forever remain rooted to the country of her birth and tied to the notion that whatever had come before was preferable to an uncertain present.

The First Gulf War and her father’s death soon after she left school brought profound changes to Maysoun’s life in Baghdad, bestowing on her the role of her mother’s companion and widening her horizons to the many ways in which things could suddenly go wrong, not only for herself but for an entire country and its people. After the allied campaign led to the killing of thousands of retreating Iraqi troops and as many innocent civilians, the crippling effects of international sanctions introduced by the West began to make themselves felt. Maysoun saw herself carried along by a wave of events that she could neither control nor avoid: the first inkling of the harsh lessons that lay ahead. When she thinks now of what was to follow, of her own feeble attempts at struggle against an inexorable deluge, she feels a certain regret; she wishes that things could have turned out differently although she harbours a strong belief that God’s will always prevails, that she might have grown stronger for the experience, might have been something other than this undefined, absent self.

She has the colouring of her father’s Kurdish ancestry somewhere in the family’s still unknown past, a great-grandfather, perhaps, or one even further back – no one has ever managed to find out. Her fair hair and hazel eyes and skin that is clear and smooth afford her a fragile loveliness uncommon in this part of the world, though it is beauty that with age has softened, become less startling, less of an encumbrance to her daily life. Thinking of her one great love, she is satisfied with the recollection of the myriad ways in which he had looked at her, the wonder and mystery in his eyes and the desire that died with him all those years ago, youth and vision left behind.

In Beirut, getting up and dressing for work in the morning, Maysoun hesitates for a moment before reluctantly opening the bedroom shutters to the noises of the street below. Her second-floor apartment in a popular Ras Beirut neighbourhood makes lasting isolation difficult; it lets in the good and the bad, the brilliant sunlight and the hum of people, the dust and diesel fuel that cause her debilitating allergies, and an inkling that she is part of something animate, breathing, even if she does not wish to be. Sometimes, on the rare occasions when she miraculously wakes to acceptance, the certainty that she is enveloped by God’s grace and is worn and defenceless no longer propels her into action.

Since settling here some years ago, she has fashioned for herself an existence that infuses her dreams with calmness but which, in the stark light of day, gives her only reluctant refuge. Often, awakened by the reality of her situation, she cringes at this bustling brawling city and sinks into forgetfulness, imagining the world that might have been, a history uninterrupted by violence and circumstance.

She tells herself that staying on in Baghdad would have been impossible after all that had happened to her there, that despite her attachment to her mother and to memories of home, she had done well to seek a life elsewhere, in a city that, though not ideal, was still in the region and did not have hell and torment in it.

Insidiously, the present always manages to cut short her reveries. In her work in Beirut with refugees from Iraq and now Syria also, in her efforts to survive the ignominy of being and feeling herself displaced, in the relationships she has formed with people, sometimes despite herself, and everywhere her body takes her, through motions and ministrations, the weight of misgivings exhaust her physically as well as in spirit.

And yet, and yet, there are small pleasures that greet her at the beginning of each day. The rhythm of her walk to the office, up a gentle hill and then down again, and the gratifying familiarity of it; the first cup of coffee of the day which she buys from a place near work, milky and sweet just as she’s always liked it; the quiet, reciprocated greetings she receives from her colleagues when she arrives at the office; and that moment when, finally sitting at her desk to deal with the tasks at hand one by one, she is aware of a beginning and an end to things and is inordinately comforted by that thought.

Chapter 5 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

Maysoun is still at work when Peter drops by to see her on his way home.

—I thought I would be too late to catch you, he tells her as they embrace.

—You would have been in another ten minutes. She smiles. It’s good to see you, Peter. How are you? How is Hannah? It’s been too long since we last saw one another.

—All is well, alhamdulillah, he replies. And you?

She smiles.

—I like it when you speak Arabic. It becomes you.

—Even though I’ve got a long way to go before I begin to speak like a native? He laughs.

—Sit down, Peter. She gestures towards a chair opposite her desk.

—I won’t keep you too long. I just wondered if you could do me a favour.

—Yes, of course. Tell me what you need.

Peter had liked Maysoun from their first meeting at a conference on Iraqi refugees who were being processed through Lebanon and on to destinations further away. There was a simplicity, an honesty about her, that immediately attracted him, as did her gentle beauty. He had introduced himself and invited her to dinner at home with Hannah. He had sensed, also, the solitude that surrounded her, though she clearly did not suffer from loneliness, her reserve lending her an air of self-sufficiency that was strangely calming to him. Hannah had also liked her, for the same reasons he had, and it was not long before the friendship was perceived, on both sides, as a particular privilege.

Maysoun’s story moved them once they heard it, though after its disclosure and the initial impact it made, it was not referred to among them again. This was less a function of his and Hannah’s discretion, than because, Peter thought, Maysoun herself had employed no drama in the telling of it so that the greatest impression left on them was that of deep sadness, of a gradual but inexorable weakening of the threads that hold the self together. When he and Hannah had occasion later to speak about it, it was with the realization that their respect for Maysoun, for her resilience in the face of so many challenges, could only grow with time.

She listens patiently to the details Peter gives her of Anas’s story and his concern about the whereabouts of his family before commenting on it.

—Yes, we have the means to trace them, she says. Why don’t you tell him to come here to put in an official request whenever he’s ready?

—Thanks for that, Maysoun. I’ll tell Anas to get in touch with you. But I don’t want to keep you here any longer. Shall we walk together?

—Yes, Maysoun says. That would be nice.

In just the past year, Beirut has changed in many ways that are sometimes difficult for him to pinpoint but which once they occur seem immediately familiar. The many beggars in the street who grow increasingly insistent, even at times aggressive; the obvious weariness in people’s eyes as they go past; half-empty restaurants; a pall, a greyness that depresses him; a disconnection that instead of feeling like release, brings on disquiet.

He remembers his childhood in Detroit so clearly, he thinks now, because it is a past that contrasts dramatically with his present. He recalls an almost antiseptic quality to those days, an absence of discord and tension that his parents, white, middle-class and liberal, only served to confirm.

Growing older, he had found himself being drawn to the children of immigrants, people whose lives seemed coloured by a chaos and passion unfamiliar to him. Many of his friends were Arab; one in particular became a constant companion, a Lebanese boy whose older sisters were blessed with an exotic beauty that drew Peter even then: the same dark, deep eyes of his future wife, the same impenetrable reserve, hair and skin contrasting like shadow and light, and an almost imperceptible trembling beneath the surface that suggested heightened awareness.

It was not long before mixing, eating and living with families whose lives were prescribed by the customs they had brought with them from far-off places made Peter feel he was acquiring a new identity, one that fell somewhere between bland and overspilling, but which nonetheless did not fit in places. But he only grew more confused about his identity with time; he left school believing he would find it, not in the direction in which his past was bound to lead him, but in the unforeseen future, where experience would lend him the clarity and skill to realize his true self.

At medical school, his days ruled by exams, exhaustion and unrelenting illness, he had finally found the direction he needed, had worked hard to fill the gaps created by a wandering mind, discovered purpose where he had once known only ambiguity.

Perhaps it was inevitable that when he met Hannah while on a visit to Beirut with his Lebanese friend one summer, Peter had been immediately drawn to the unfamiliar in her; sensed also, as they spent more time together, the same inquisitiveness that had propelled him when he was younger, though in Hannah curiosity was hardly a quiet pursuit. Before long, he had recognized an attachment to her that he knew would not fade once he returned to America to complete his studies. There was much at stake for him by then: a job at a prestigious teaching hospital on the East Coast where he would specialize in paediatrics; yet beyond that there was the pull of a woman and her beloved city that would dictate the trajectory of life to come.

When he returned to Beirut two years later, Hannah was waiting as he had known she would be, and since civil marriage is not legal in Lebanon – Hannah and Peter were born into different faiths – they decided to fly to Cyprus and marry there. With time, Peter discovered that while his love for his wife grew steadily, he was less able to articulate it, as though its increasing depth made it more mysterious and inaccessible to him, as though it had expanded to embrace much more than either of them could put into words.

More and more, though, as conflict spreads throughout the region and Lebanon trembles in the midst of it, he senses resistance in himself to the uncertainty of it all, finds it increasingly difficult to separate place from people, to disconnect his love for Hannah from the country to which she belongs.

—Perhaps it’s me, he finds himself saying out loud.

—Peter?

—I’m just thinking, is it that I’m feeling despair or is it just that I seem to be surrounded by it these days?

Maysoun smiles.

—Probably something of both, she says.

They walk up Sadat Street and turn right in the direction of the sea and towards Maysoun’s building.

During Peter’s first visit to Beirut, he had enjoyed the quirkiness of the city’s byways, the narrow limits of neighbourhoods that, in the minds of locals, were marked and distinctive. Asking for directions elicited conversation rather than providing the information he sought. Often, he would be told to keep walking straight ahead and ask someone at the next corner, or if he were after something in particular to buy, he would be directed to a completely different shop where, he was assured, he could find a better product.

Once, stopping to ask an old man sitting at the entrance to a building where the nearest pharmacy was located, he was surprised by the response.

—Why do you need the pharmacy? the old man asked.

At first, Peter was too astonished to reply.

—I … I have a cough and I need to get some medication for it, he said in halting Arabic.

The old man looked up at him with rheumy eyes and made a disapproving sound with his tongue.

—Tsk, tsk, tsk. You young people don’t know how to take care of yourselves, do you? Not wearing the right clothes in the cold, going in and out of air-conditioned rooms with hardly anything on. What do you expect? Of course you’re going to get sick.

After which, and to Peter’s great amusement, the old man grudgingly directed him to a nearby pharmacy as well as advised him what medication he should ask for.

Eventually, Peter became aware of an invisible connectedness between people and places here, a kind of map of everyday relationships, of being, that was easy to follow once you knew how and made for a sense of rootedness which he had not encountered anywhere else.

It seems to him that while in Western societies the inner lives of people tend to shape their existence, the oppo-site is true in this part of the world where the external is what dominates lives. Perhaps it is a function of the fact that in the West, there is much about one’s environment that one can take for granted and, therefore, safely ignore. Peter believes that this is the case only in part, that reality is more complicated, that there is a willingness to concede to fortune in this society that helps people cope: not fatalism exactly but a genuine recognition that acceptance is sometimes the best option in circumstances over which one has no control.

—Sometimes, he says out loud, I think I will never be able to shake off the influences of my background.

Maysoun turns to him and, as she does so, he looks on in fascination as the fading sunlight touches her face, her transparent skin, her eyes, sharp and knowing.

—But why would you want to? she asks. Why would you ever want to let go of the one thing that defines you, Peter?

Chapter 6 (#ua46d5611-62ea-5b29-b2b4-caa475ad3c19)

Hannah’s father lives in the apartment where she and her brother had been brought up, near the sea – though the apartment does not look directly on to it – a neighbourhood which her father says was once the wilderness of Ras Beirut, where jacaranda and lemon trees grew in profusion and, at dusk, the sun swept over vast fields of tall grasses, over the water, in ever-widening arcs of amber reds.

—This, Faisal always tells her in his shaky old voice, was long before you were born, Hannah, when I was a young boy and my brothers and I would come here to play after school despite your grandmother having forbidden it.

She smiles and reaches over to touch his hand.

—Often, we stayed out so late that our father would come looking for us, he continues, calling out to each of us by name in such a beautiful, deep, sing-song voice that we would hide further in the bushes, out of sight, just to listen to it.

—The way you describe it, Baba, Hannah tells him, it’s not difficult for me to imagine what it was like for you, the joy in that freedom.

Faisal pauses before going on.

—This building is located on the same site where your uncles and I used to play but it was not put up until years later. The moment I saw the foundations being dug, I was determined to live in it, although I was still a student at university at the time and couldn’t possibly afford the rent. As soon as I got myself a decent job, I took this apartment and brought your mother here after we were married. Eventually, of course, we were able to buy it and really call it home. He sighs. Life was simpler then, you know. There was more cohesiveness between communities and Beirut seemed much smaller because even when people did not know one another, they were at least familiar with each other’s families.

During her almost daily visits to her father, with every telling of these now familiar stories, Hannah finds herself searching for details that she might have previously missed, for the one element that could change her perception of the whole and bring greater clarity with it. What she seeks is not so much to understand the everyday history of this city that came before, but rather to picture it plainly in her mind’s eye and so commit herself to its past, to make for herself tangible memories of another Lebanon, a country built on hope and expectations of better times to come, a home that lived in the hearts and minds of its people.

She has some clear memories of life in Beirut as a child, before the outbreak of civil war and the family’s consequent escape to Cyprus, memories that are mostly associated with her family, and with her mother especially, young and lovely, her clean scent and dark hair shining. She remembers the way her mother would put out a hand for hers just before they went out, the feel of those soft fingers and, when she looked down, their beautifully manicured nails. As they walked then, Hannah trying desperately to keep up with her mother’s long strides, the streets of Beirut seemed to reflect the buoyancy they both felt, the glowing in their hearts.

Once, accompanying her mother on a visit to the home of friends, Hannah had found herself in an enormous living room, the sea – beyond luminous in the sun – framed by the huge window at one end of it. She saw waves that peaked in white and dipped down again into the blue, light bouncing on water and, in the distance, the long line of horizon glimmering, turning pale as it edged towards the sky so that Hannah felt herself lifted into it as she stood, hands leaning against the glass, her tiny body tilting towards the view, melting into it.

There had been family trips to the mountains where Hannah’s aunt Amal and her family spent their summers in a stone house that on one side overlooked terraces of pistachio trees and on the other abutted a hill covered in brambles. Lunch was eaten around a large table placed beneath the shade in the front garden: salads, stews and vegetables stuffed with rice and nuts, and raw meat pounded until tender, wrapped in mountain bread and dipped in seasoning. Afterwards, Hannah and her two cousins – her brother Sammy was an infant still – would tear squares off cardboard boxes they had found in the kitchen and carry them up the hill to a plateau midway on the mountain, high enough that the house looked no bigger than a matchbox but was visible still, and would sit on the cardboard and slide all the way down again, red dirt flying, arms and hearts thrown asunder.

These images, though vivid, are so fragile, so quick now to escape her even as she tries to recall them, that making of them a complete and satisfying picture seems impossible nowadays. In conversation with her father and other elderly relatives, and during moments of solitary contemplation, she fears that Lebanon, tired and faded as it has become, will never again award her that enchantment, that same, untainted delight.

She gets up to greet her father’s housekeeper in the kitchen and asks her to make tea before returning to the living room with the pot and placing it on the coffee table. Her father is facing the French doors that lead out to the balcony and she, with her back to the light, looks only at him. Although thin and somewhat shrunken with age, Faisal still, Hannah believes, retains the sense of presence he has always had, with his intelligent eyes and the calmness about him that is evident as soon as one comes near, into a welcoming orbit of tranquillity.

They are silent, enjoying the wet, rippling sounds of tea being poured and sipped, comforting noises that are filled with memories for both of them.

Hannah has always loved the stillness she can share with her father, periods of relief that she did not experience with her mother, who was mostly occupied with verbally identifying things that needed to be done and then doing them with equal vigour. Hannah attributes these gaps in conversation to an older generation of Lebanese, pauses that provide them the opportunity to realign themselves with what is at hand, to assess a situation before acting on it. As a girl she distinctly remembers sitting patiently in rooms filled with people when a sudden quiet would prevail and, to her surprise and discomfort, no one but herself would try to fill it. It is a lesson she identifies with patience and love because neither of these two qualities, she now realizes, can exist without the other.

—Hannah, hayati – her father looks searchingly at her – is everything all right?

She is puzzled by his question.

—You seem preoccupied about something, he adds.

—It’s the usual worry, I guess. Just concerned about the state of things. Sometimes I think we’re never going to know what security is in this country. I’m working on a series of articles for a British newspaper and the more I discover about what’s going on in this part of the world, the more despair I feel.

For a long time he does not say anything and she begins to think he might be dropping off in the silence.

—I was seventeen when the war began, Faisal finally says. All hell was breaking loose in Europe, but to us here it seemed a million miles away.

Hannah suddenly realizes that her father is referring to the Second World War.

—Even while millions were dying and the map of the world was being redrawn, he continues, we were lost in our own troubles, trying to fight for this country’s freedom from French control. I joined youth groups and went to meetings and took part in demonstrations calling for independence. Some of these activities were punishable by death at the time, you know. People were accused of sedition and hanged for a lot less by the Mandate authorities.

—The martyrs who fought for our independence, Hannah exclaims. We were taught about them at school.

Her father nods and continues.

—It was all such a long time ago that sometimes I have difficulty recalling exactly the feelings associated with it, the uncertainties and the anticipation. But what I cannot forget is the sense of urgency that surrounded those times, an urgency that made us think this period would never come to an end. We were wrong though.

—About the success of the fight?

—Maybe it’s just that we got older and too cynical to care, he says.

—Not cynical, she tells him. You were just caught up with the vagaries of everyday life.

During our exile to Cyprus while Lebanon’s civil war raged on, Father would come to visit every few weeks, staying just long enough to remind us of himself, so that sometimes it seemed he had been with us only in dreams, so fleeting was his presence, so light the grooves he left on my heart. Although I resented his absence at the time, I later understood that this impression of impermanence had less to do with the time that he spent with us than where he spent it. Father was only half himself when away from Lebanon, not because he had been diminished for want of home but because everything about him that was most true had Lebanon as its anchor.

Hannah wonders for a moment if this is also now true for her, if in leaving Lebanon, she might find it difficult to keep the pieces of herself together. Remaining whole would be impossible. She recalls that when she had first told Faisal of her decision to marry Peter, he asked her if she intended to go to America with him.

—He will remain here to be with us, Baba, Hannah had reassured him. We will be his home.

Her father had smiled and said nothing more.

She gets up and stands behind Faisal’s chair, bending down to wrap her arms around him. A breeze comes in through the French doors and they smell the sea in it as it blows gently on to their faces.

—Thank you, Baba, Hannah whispers into the old man’s ears. Thank you, habibi.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_1904e544-7183-5224-a24d-534af1659aa1)

On the drive back to Beirut, a few days later, Hannah is aware of almost overwhelming tiredness. She has been to numerous encampments, has spoken to dozens of refugees and noted so many disturbing stories that she is not sure where or how she might begin telling them.

Rifling through her bag, she takes out a thick pile of the small, lined notebooks she uses for interviews and attempts to sort through them. Would arranging them by region be best, she wonders, the regions in Syria from where the refugees have come or the areas of Lebanon where they consequently settled? Should she focus on communities, the number of Shia, Sunni, Christian or Druze who have fled, or is it more important that she keep the most horrifying stories uppermost in her mind, the family members killed in bombings, for example, the homes and communities destroyed, the injuries sustained, the accounts of children traumatized by what they have seen and experienced, the beheadings, beatings and barbarism they witnessed, or the anguish felt by their elders at leaving homes and property behind and the harrowing tales of escape?

At moments like these, she recognizes the advantage photojournalists and television reporters have in covering tragedy; pictures say more than words ever could, their impact is immediate, their portrayal of suffering and urgency unequivocal. She suspects that whatever she eventually writes will not manage to express what she knows is true: the unyielding pull of despair, and, despite the odds, the inexorable reality of expecting something better.

She thinks of their eyes especially, questioning, pleading and trusting eyes; she still feels the small hands of children grasping tightly on to hers; she pictures the recognition on the faces of the women and men she met of a shared humanity, of the potential in meeting like this, in chronicling these extraordinary events.

Of all the images that struck her today, the one she cannot stop thinking about is the clothes line that had hung around the outside of one of the tents in the last encampment, the children’s clothes, a neat procession of trousers and shirts, jeans and pyjamas, diminutive and faded, appealing to her in a way she could not explain. Ahead, on either side of the dirt path, stretched two long rows of these makeshift tents, sheets of white tarpaulin with the UNHCR name and logo stamped on to them mounted on to wooden slabs to create a semblance of space, a suggestion of privacy. It would not have occurred to her that the refugees would be so proud of these simple dwellings, the men for having put them up with their own hands, the women for maintaining order in them, but this was exactly what she had sensed as her feet came to an abrupt stop and all she could do was stare at the clothes line in wonder.

The skinny young man with the gelled-back hair who had agreed to show her around the campground when she first arrived stood beside her, quiet though clearly waiting for some sign of willingness on her part to go ahead with the tour. She had felt his presence like a hum on the outlines of her skin, was conscious of his expectation, but still she could not move.

Above, the sky was blue, though she had a momentary impression of it descending gradually towards her in the breeze that touched her hair and blew gestures into the children’s garments, trousers lifting forward as if on a swing, a bright pink top simulating a wave with its sleeve.

It astonished her that she could make out too the scenes that had unfolded behind her as she advanced: the tiny mobile clinic where a heavily bearded young doctor treated minor cuts and bruises and dispensed medications to a queue of refugees waiting outside; the movement of people in and out of the encampment with the sound of traffic from a nearby highway electrifying the air; the stench emanating from the filthy, rubbish-filled stream that ran alongside the camp which, according to the doctor, was the principal reason behind the infestation of parasites in the systems of so many of the children in the camp; the glassed-in caf? where she and the taxi driver had stopped for refreshment midway through their journey, the sweet, tangy taste of homemade lemonade and the little boy, brown and dirty, who had stood begging at the caf? entrance and smiled when she bought him a sandwich and a drink; the shopkeeper who had directed them to the encampment, muttering under his breath something about the plague of refugees who had descended on the area; the checkpoint they had passed earlier that morning on the road leading down to the eastern Bekaa, where young soldiers, one of whom had a cut on his cheek that oozed a thin trickle of blood down his face, waved them on; the trip from Beirut and she turning back to wave to Peter out of the car window, calling out that she would see him later that evening; and, most of all, the sudden indisputable certainty she had gained that in coming here, in being a part of this, however briefly, she was experiencing intervals of peace.

Leaving the village of Bar Elias behind, we make our way back, Saturday-afternoon traffic leading through the town of Chtoura and on to the capital Beirut heavy and slow. In the back of the taxi, my journalist’s paraphernalia is scattered on the seat beside me: pencils and several notepads; copies of UNHCR reports listing refugee numbers, aid disbursement and other statistics; an old map so embarrassingly out of date that it describes Lebanon as a country of merely three million people, the majority of whom being Maronite Christians; and somewhere out of sight, hidden beneath the mess that also includes an empty water bottle and the remains of a packet of biscuits the driver and I shared on our way over this morning, is a disposable camera which I will have developed and give my colleague from England to use for reference when he takes the professional photographs that will accompany this article.

The pictures, I know, will describe events in a way that no words, no matter how eloquent, ever can; will pull at heartstrings without the added encumbrance of intellect and reason. I put my pencil down and stare out at the shifting landscape, feeling remorse for the stories that slip from my fingers every time I attempt to write them down.

Chapter 8 (#ulink_22b2f451-a60e-5674-9b39-a714a8ad4ad3)

It happens as they make their way back home, discussing the possible outcome of Maysoun’s search for Anas’s family, wondering what else they can do or say to comfort their friend.

They stop to cross the street at a busy intersection a few minutes away from their building, a traffic light that most drivers and pedestrians tend to ignore, and observe the chaos as drivers manoeuvre their vehicles through narrow gaps in the traffic, past cars that are double-parked on either side and between darting pedestrians. The small shops on either side of the road are also busy, women buying groceries on their return home from work, children running in and out of stationers for school supplies, people waiting to be served outside a sweetshop famous for its baqlawa and, on the pavement, constant movement.

Hannah is nervous because a group of refugees congregated at the intersection, as usual, do not seem wary enough of the cars whizzing past. It is getting dark and the street lights have not come on yet. The refugees are like shadows, she thinks, colourless and in some ways invisible to everyone else. She has seen them here before, remembers especially a young woman with a very young boy sitting together on the median strip running down the centre of the road. When night begins to fall, Hannah has watched the young woman wrap the boy tightly in her arms, both of them sitting very still, the little boy’s head on his mother’s shoulder, eyes open and searching. It is a disturbing sight.