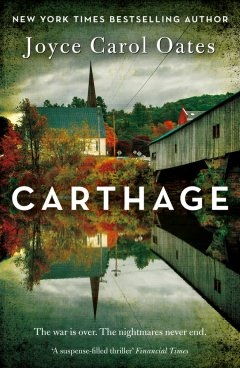

Carthage

Àâòîð:Joyce Oates

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:1109.06 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 405

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 1109.06 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Carthage

Joyce Carol Oates

A young girl’s disappearance rocks a community and a family, in this stirring examination of grief, faith, justice and the atrocities of war, from literary legend Joyce Carol Oates.Zeno Mayfield’s daughter has disappeared into the night, gone missing in the wilds of the Adirondacks. But when the community of Carthage joins a father’s frantic search for the girl, they discover instead the unlikeliest of suspects – a decorated Iraq War veteran with close ties to the Mayfield family. As grisly evidence mounts against the troubled war hero, the family must wrestle with the possibility of having lost a daughter forever.‘Carthage’ plunges us deep into the psyche of a wounded young Corporal, haunted by unspeakable acts of wartime aggression, while unraveling the story of a disaffected young girl whose exile from her family may have come long before her disappearance.Dark and riveting, ‘Carthage’ is a powerful addition to the Joyce Carol Oates canon, one that explores the human capacity for violence, love and forgiveness, and asks it it’s ever truly possible to come home again.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_a2e81353-7e21-5c66-b4ac-2c8b7ff283ab)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

FIRST EDITION

Copyright © The Ontario Review 2014

Joyce Carol Oates asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

Cover design by Allison Saltzman

Cover photograph © Denis Jr. Tangney/Getty images

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007485741

Ebook Edition © January 2014 ISBN: 9780007485765

Version 2014-11-18

DEDICATION (#ulink_456ca842-a0f8-55ec-9aae-639a33911f5e)

To Charlie Gross

my husband and first reader

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#ulink_0350fc82-62ce-5eec-bf67-354264c652b5)

A shortened version of chapter two appeared in Fighting Words, edited by Roddy Doyle, 2011.

Thanks to former Marine Mariette Kalinowski, Sergeant, USMC (ret.), and to Martin Quinn for reading this manuscript with special care as Hertog Research Fellows at Hunter College, and thanks to Greg Johnson for his continued friendship, sharp eye and ear, and impeccable literary judgment.

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_1727e5f3-e524-5769-aedd-53d6f973abb0)

“Go at once, this very minute, stand at the cross-roads, bow down, first kiss the earth which you have defiled and then bow down to all the world and say to all men, ‘I am a murderer!’ Then God will send you life again.”

—SONIA TO RASKOLNIKOV, IN CRIME AND PUNISHMENT, FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY

I don’t feel young now. I think I am old in my heart.

—AMERICAN IRAQ WAR VETERAN, 2005

CONTENTS

Cover (#u70246efd-b8d7-584c-8d7a-1c6403efc6eb)

Copyright (#ulink_3eaf7f9c-6a72-5ffd-814b-c38dd4e4db36)

Dedication (#ulink_7950aa73-e95d-53f0-9d86-aa4c65ae92c1)

Acknowledgments (#ulink_8e25f05f-af06-554d-a908-f3060ee3dfeb)

Epigraph (#ulink_409d7b26-86ba-52bd-a50e-d0a6b49e83e1)

Prologue (#ulink_7e302103-6736-5fdd-aa25-f2499a0afa71)

Part I: Lost Girl (#ulink_6f5f6c6b-5fde-5ef9-8eb9-a248d1783f08)

One - The Search (#ulink_e1621c6b-f242-512f-a815-8243aadfc9fd)

Two - Bride-to-Be (#ulink_483c53ad-3812-5d46-9139-caf74fc897bf)

Three - The Father (#ulink_c70ccc4a-96bb-5f6d-921d-c508b8ba8190)

Four - Descending and Ascending (#ulink_2a6eed4d-b81b-5b06-813a-b63e8b24dbe8)

Five (#ulink_0a581d2e-f3bb-5755-ad1e-a2dad9929ae4)

Six - The Corporal in the Land of the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven - The Corporal’s Confession (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight - The Corporal’s Letter (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II: Exile (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine - Execution Chamber (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten - The Betrayal (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven - The Rescue (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve - The Guilty One (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III: The Return (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen - The Long Wall (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen - The Church of the Good Thief (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen - The Father (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen - The Mother (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen - The Sister (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Novels by Joyce Carol Oates (#litres_trial_promo)

Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE (#ulink_9ee0a204-48e2-54fd-9102-35a9c59f7999)

July 2005 (#ulink_9ee0a204-48e2-54fd-9102-35a9c59f7999)

DIDN’T LOVE ME ENOUGH.

Why I vanished. Nineteen years old. Tossed my life like dice!

In this vast place—wilderness—pine trees repeated to infinity, steep slopes of the Adirondacks like a brain jammed full to bursting.

The Nautauga State Forest Preserve is three hundred thousand acres of mountainous, boulder-strewn and densely wooded wilderness bounded at its northern edge by the St. Lawrence River and the Canadian border and at its southern edge by the Nautauga River, Beechum County. It was believed that I was “lost” here—wandering on foot—confused, or injured—or more likely, my body had been “dumped.” Much of the Preserve is remote, uninhabitable and unreachable except by the most intrepid hikers and mountain climbers. For most of three days in midsummer heat rescue workers and volunteers were searching in ever-widening concentric circles spiraling out from the dead end of an unpaved road that followed the northern bank of the Nautauga River three miles north of Wolf’s Head Lake, in the southern part of the Preserve. This was an area approximately eleven miles from my parents’ house in Carthage, New York.

This was an area contiguous with Wolf’s Head Lake where at one of the old lakeside inns I’d been last seen by “witnesses” at midnight of the previous night in the company of the suspected agent of my vanishing.

It was very hot. Insect-swarming heat following torrential rains in late June. Searchers were plagued by mosquitoes, biting flies, gnats. The most persistent were the gnats. That special panic of gnats in your eyelashes, gnats in your eyes, gnats in your mouth. That panic of having to breathe inside a swarm of gnats.

Yet, you can’t cease breathing. If you try, your lungs will breathe for you. Despite you.

Among experienced rescue workers there was qualified expectation of finding the missing girl alive after the first full day of the search, when rescue dogs had failed to pick up the girl’s scent. Law enforcement officers had even less expectation. But the younger park rangers and those volunteer searchers who knew the Mayfields were determined to find her alive. For the Mayfields were a well-known family in Carthage. For Zeno Mayfield was a man with a public reputation in Carthage and many of his friends, acquaintances and associates turned out to search for his missing daughter scarcely known to most of them by name.

None of the searchers making their way through the underbrush of the Preserve, into ravines and gullies, scrambling up rocky hillsides and climbing, at times crawling across the mottled faces of enormous boulders brushing gnats from their faces, wanted to think that in the Adirondack heat which registered in the upper 90s Fahrenheit after sunset a girl’s lifeless body, possibly an unclothed body on or in the ground, sticky with blood, would begin to decompose quickly after death.

None of the searchers would have wished to utter the crude thought (second nature to seasoned rescue workers) that they might smell the girl before they discovered her.

Such a remark would be uttered grimly. Out of earshot of the frantic Zeno Mayfield.

Shouting himself hoarse, sweat-soaked and exhausted—“Cressida! Honey! Can you hear me? Where are you?”

He’d been a hiker, once. He’d been a man who’d needed to get away into the solitude of the mountains that had seemed to him once a place of refuge, consolation. But not for a long time now. And not now.

In this hot humid insect-breeding midsummer of 2005 in which Zeno Mayfield’s younger daughter vanished into the Nautauga State Forest Preserve with the seeming ease of a snake writhing out of its desiccated and torn outer skin.

PART I (#ulink_fe786d2f-8ce5-5c5f-bcbd-20343062f7a9)

Lost Girl (#ulink_fe786d2f-8ce5-5c5f-bcbd-20343062f7a9)

ONE (#ulink_bb0de8f5-288a-56c8-86a2-1ed35df59cd1)

The Search (#ulink_bb0de8f5-288a-56c8-86a2-1ed35df59cd1)

July 10, 2005 (#ulink_bb0de8f5-288a-56c8-86a2-1ed35df59cd1)

THAT GIRL THAT GOT lost in the Nautauga Preserve. Or, that girl that was killed somehow, and her body hid.

Where Zeno Mayfield’s daughter had disappeared to, and whether there was much likelihood of her being found alive, or in any reasonable state between alive and dead, was a question to confound everyone in Beechum County.

Everyone who knew the Mayfields, or even knew of them.

And for those who knew the Kincaid boy—the war hero—the question was yet more confounding.

Already by late morning of Sunday, July 10, news of the quickly organized search for the missing girl had been released into the rippling media-sea—“breaking news” on local Carthage radio and TV news programs, shortly then state-wide and AP syndicated news.

Dozens of rescue workers, professional and volunteer, are searching for 19-year-old Cressida Mayfield of Carthage, N.Y., believed to be missing in the Nautauga State Forest Preserve since the previous night July 9.

Corporal Brett Kincaid, 26, also of Carthage, identified by witnesses as having been in the company of the missing girl on the night of July 9, has been taken into custody by the Beechum County Sheriff’s Department for questioning.

No arrest has been made. No official statement regarding Corporal Kincaid has been released by the Sheriff’s Department.

Anyone with information regarding the whereabouts of Cressida Mayfield please contact . . .

HE KNEW: she was alive.

He knew: if he persevered, if he did not despair, he would find her.

She was his younger child. She was the difficult child. She was the one to break his heart.

There was a reason for that, he supposed.

If she hated him. If she’d let herself be hurt, to hurt him.

BUT HE HAD no doubt, she was alive.

“I would know. I would feel it. If my daughter was gone from this earth—there would be an emptiness, unmistakably. I would feel it.”

HE HATED THAT she was identified as missing.

He’d insisted that she was lost.

That is, probably lost.

She’d wandered off, or run off. Somehow, she’d gotten lost in the Nautauga Preserve. The young man she’d been with—(this, the father didn’t understand: for the daughter had told her parents that she was going to spend the evening with other friends)—had insisted he didn’t know where she was, she’d left him.

In the front seat of the young man’s Jeep Wrangler there were said to be bloodstains. A smear of blood on the inside of the windshield on the passenger’s side, as if a bleeding face, or head, had been struck against it with some force.

Stray hairs, and a single clump of hair, dark in color as the hair of the missing girl, had been collected from the passenger’s seat and from the young man’s shirt.

Outside the vehicle there were no footprints—the shoulder of Sandhill Road was grassy, and then rocky, declining steeply to the fast-rushing Nautauga River.

The father didn’t (yet) know details. He knew that the young corporal had been taken into police custody having been found in a semiconscious alcoholic state inside his vehicle, haphazardly parked on a narrow unpaved road just inside the Nautauga Preserve, at about 8 A.M. of Sunday, July 10, 2005.

Allegedly, the young corporal, Brett Kincaid, was the last person to have seen Cressida Mayfield before her “disappearance.”

Kincaid was a friend of the Mayfield family, or had been. Until the previous week he’d been engaged to the missing girl’s older sister.

The father had tried to see him: just to speak to him!

To look the young corporal in the eye. To see how the young corporal looked at him.

The father had been refused. For the time being.

The young corporal was in custody. As news reports took care to note No arrests have yet been made.

How disorienting all this was!—the father who’d long prided himself on being smart, shrewd, just a little quicker and a little more informed than anyone else was likely to be in his vicinity, could not comprehend what seemed to be set out before him like cards dealt by a sinister dealer.

His life—his life of routine complex as the workings of an expensive watch, yet unfailingly in his control—had been so abruptly altered. Not just the surprise—the shock—of his daughter’s “disappearance” but the circumstances of the “disappearance.”

It was not possible that Cressida had lied to him and to her mother—and yet, obviously, it seemed that Cressida had lied.

At any rate, she’d told them less than the truth about where she’d planned to go the previous night.

How out of character this was! Cressida had always scorned lying as moral weakness. It was cowardice to care so much of others’ opinions, one would stoop to lie.

And that she’d met up with her sister’s ex-fianc?, at a lakeside inn—that was even more astonishing.

The Mayfields had to tell police officers—they’d had to tell them all that they knew. It wasn’t police procedure to search for an adult who has been missing for such a relatively short period of time unless “foul play” is suspected.

The father had to insist that he was concerned that his daughter was “lost” in the Nautauga Preserve even as he couldn’t bring himself to acknowledge the possibility that she’d been “hurt.”

Or, if “hurt”—“seriously hurt.”

Not wanting to think sexually abused, raped.

Not wanting to think And worse . . .

Cressida was nineteen but a very young nineteen. Small-boned, childlike in her demeanor, with the body of a young boy—lithe, narrow-hipped, flat-chested. The father had seen men—(not boys: men)—staring at Cressida, especially in summer when she wore baggy T-shirts, jeans or cutoffs, her striking face pale without makeup; staring at Cressida in a kind of baffled yearning as if trying to determine if she was a young girl or a young boy; and why, though they stared so avidly at her, she remained oblivious of them.

So far as her parents knew, Cressida was inexperienced with boys or men.

She had the puritan ferocity of one who scorns not so much sexual experience as any sort of shared and intimate physical experience.

As her sister Juliet had said Oh I am sure that Cressida has never been—you know—with anyone . . . I mean . . . I’m sure that she’s a . . .

Too sensitive of her sister’s feelings to say virgin.

THE FATHER WAS VERY EXCITED. Adrenaline ran in his veins, his heart beat with an unnatural urgency. Telling himself This is the excitement of the search. Knowing that Cressida is near.

He felt this, his daughter’s nearness. This man who never listened with any sort of sympathy to talk of such “mystical crap” as extrasensory perception had a conviction now, tramping through the Nautauga Preserve, that he could sense his daughter somewhere nearby. He could sense her thinking of him.

Even as with a part of his mind he understood that, if she’d been anywhere near the entrance to the Preserve, anywhere near Sandhill Road and Sandhill Point, someone would have found her by now.

For he was trained in the law, and he had by nature the lawyer’s temperament—doubt, questioning, more questioning.

For he was trained to respond Yes, but—?

The father thought how ironic, the daughter had never liked camping or hiking. Wilderness was boring to her, she’d said.

Meaning wilderness frightened her. Wilderness did not care for her.

He’d known other people like that, and all of them, perhaps by chance, women. The female is most secure in a confined space, a clearly designated space in which one’s identity is mirrored in others’ eyes: in such a place, one cannot become easily lost.

The rapacity of nature, Zeno thought. You never think of it when you’re in control. And when you’re no longer in control, it’s too late.

The father glanced upward, anxiously. High overhead, just visible through the dense pine boughs, a hawk—two hawks—red-shouldered hawks hunting together in long swooping arcs.

Vivid against the sky then suddenly plummeting, gone.

He’d seen owls swoop to the kill. An owl is a feathery killing machine and silent at such times when the only outcry is the cry of the prey.

Underfoot as he pushed through briars were scuttling things—rabbits, pack rats—a family of skunks—snakes. From somewhere close by the liquidy-gobbling cries of wild turkeys.

Wilderness too vast for the girl, the younger daughter. Zeno had not liked that in her: giving up too easily. Claiming she was bored, wanted to go home to her books and “art.”

Needing to squeeze all that she could into her brain. And you can’t squeeze three hundred thousand acres into a brain.

Cressida don’t do this to us! If you are somewhere close by let us know.

The father had grown hoarse calling the daughter’s name. It was a foolish waste of energy, he knew—none of the other volunteer searchers was calling the girl’s name.

From remarks made to him, and within his hearing, the father gathered that other, younger searchers were impressed with him, so far: a man of his age, much older than they, apparently an experienced hiker, in reasonably good physical condition.

At the start of the search this seemed so, at least.

“Mr. Mayfield? Here.”

He’d drunk his water too quickly. Breathing through his mouth which isn’t recommended for a serious hiker.

“Thanks, I’m OK. You’ll need it for yourself.”

“Mr. Mayfield, take it. I’ve got another bottle.”

The young man, sleek-muscled, lean, like a greyhound or a whippet—one of the Beechum County deputies, in T-shirt, shorts, hiking boots. The father wondered if the deputy was someone who knew his daughter—either of his daughters. He wondered if the deputy knew more about what might have happened to Cressida than he, the father, had yet been allowed to know.

The father was the kind of man more comfortable overseeing others, pressing favors upon others, than accepting favors himself. The father was a man who prided himself on being strong, protective.

Still, it isn’t a good idea to become dehydrated. Light-headed. Random rushes of adrenaline leave you depleted, exhausted.

He took the water bottle. He drank.

Initially this morning they’d searched along the banks of the Nautauga River in the area in which the young corporal’s Jeep Wrangler had been parked. This was a stretch of river where fishermen came often, both marshy and rock-strewn; there were numerous footprints amid the rocks, overlaid upon one another, filled with water since a recent rain. Rescue dogs leapt forward barking excitedly having been given articles of the girl’s clothing to smell but soon lost the trail, if there was a trail, whimpered and drifted about clueless. Miles along the river curving and twisting through the rock-strewn land and then they’d decided to alter their strategy fanning out in more or less concentric circles from the Point. Some had searched for lost hikers and children previously in the Preserve and had their particular way of searching but Beechum County law enforcement strategy was to keep close together, only a few yards apart, though it was difficult where there was underbrush and masses of trees, yet the point was not to overlook what might have fallen to the ground, torn clothing in briars, scraped against a tree, any sign that the lost girl had passed this way, a crucial sign that might save her life.

The father listened to what was told to him, explained to him, with an air of calm. In any public gathering Zeno Mayfield presented himself as the most reasonable of men: a man you could trust.

He’d had a career as a man who addressed others, with unfailing intelligence, enthusiasm. But now, there was no opportunity for him to give orders to others. He felt a clutch of helplessness, in the Preserve. Tramping on foot, dependent upon his physical strength, not his more customary cunning.

But O God if his daughter was hurt. If his daughter had been hurt.

Not wanting to think if she’d fallen somewhere, if she’d broken a leg, if she lay unconscious, unable to hear them calling her, unable to respond. Trying not to think if she was nowhere within earshot, borne away in the fast-flowing river that was elevated after heavy rainstorms the previous week, thirty miles downstream to the west where the Nautauga River emptied into Lake Ontario.

Through the morning there were false alarms, false sightings. A female camper wearing a red shirt, staring at them as they approached her campsite. And her partner, another young woman, emerging from a tent, for a moment frightened, hostile.

Excuse us have you seen?

. . . girl of nineteen, looks younger. We think she is somewhere in the vicinity . . .

IN THE SEVENTH HOUR of the first-day’s search, early Sunday afternoon the father sighted his daughter ahead, less than one hundred yards away.

Jolted awake, shouting—“Cressida!”

A desperate run, a heedless run, down a steep incline as other searchers stopped in their tracks to stare.

Several saw what the father was seeing: on the farther bank of a narrow mountain stream where the girl had fallen or lain down exhausted to sleep.

Rivulets of sweat ran into the father’s eyes burning like acid. He was running clumsily downhill, sharp pains between his shoulder blades and in his legs. A great ungainly beast on its hind legs, staggering.

“Cressida!”

The daughter lay motionless on the farther side of the stream, part-hidden by underbrush. One of her limbs—a leg, or an arm—lay trailing into the stream. The father was shouting hoarsely—“Cressida!” He could not believe that his daughter was injured or broken but only just sleeping, waiting for him.

Others were approaching now, on the run. The father paid no heed to them, he was determined to reach his daughter first, to waken her, and lift her in his arms.

“Cressida! Honey! It’s me . . . ”

Zeno Mayfield was fifty-three years old. He had not run like this for years. Once he’d been an athlete—in high school a very long time ago. Now his heart was a massive fist in his chest. A sharp pain, a sequence of small sharp pains, struck between his shoulder blades. He ran on reckless, desperate, as if hoping to escape the sharp-darting pains. He was a tall deep-chested man with a broad muscled back; his hair was still thick, licorice-colored except where threaded with gray; his face that had been flushed from the exertion of hours in the Adirondack heat was now draining of blood, mottled and sickly; his heart was pounding so laboriously, it seemed to be drawing oxygen from his brain; at such a pace, he could not breathe; he could not think coherently: his thick clumsy legs could hardly keep him from falling. He was thinking She is all right. Of course, Cressida is all right. But when he reached the mountain stream he saw that the thing on the farther bank wasn’t his daughter but the carcass of a partly decomposed deer, a young doe, the still-beautiful head lacking antlers and a jagged bloody section of her chest torn away by scavengers.

The father cried out, in horror.

A choked animal-cry, as if he’d been kicked in the chest.

The father fell to his knees. All strength drained from his limbs.

He’d been searching for the daughter since ten o’clock that morning. And now he’d found his daughter asleep beside a little mountain stream like a girl in a child’s storybook and in front of his eyes his daughter had been transformed into a hideous decaying carcass.

Zeno Mayfield hadn’t wept since his mother’s death twelve years before. And then, he hadn’t wept like this. His body shook with sobs. A terrible pity for the killed and part-devoured doe overcame him.

His name was being called. Hands beneath his armpits, lifting.

Wanting to hide from them the obvious fact that he was having difficulty breathing. Pains between his shoulder blades had coalesced into a single piercing pain like cartoon zigzag lightning.

He’d insisted early that morning, he would join the search team in the Preserve. Of course, the father of the missing girl must search for her.

They had him on his feet now. The wounded beast swaying.

It is a terrible thing how swiftly a man’s strength can drain from him, like his pride.

These were young volunteers, Zeno didn’t know their names. But they knew his name: “Mr. Mayfield . . . ”

He pushed their hands from him. He was upright, and he was breathing normally again, or—almost.

Would’ve insisted upon returning to the search after a few minutes’ rest, lukewarm water out of the Evian bottle and a nervous splattering urination behind a lichen-pocked boulder but blackness rose inside his skull another time, to his shame he sighed and sank into it.

GOD TAKE ME instead of her. If you take anyone—take me.

TWO (#ulink_240df0a5-b5ae-5059-b39b-de7eca6e0328)

Bride-to-Be (#ulink_240df0a5-b5ae-5059-b39b-de7eca6e0328)

July 4, 2005 (#ulink_240df0a5-b5ae-5059-b39b-de7eca6e0328)

YES YOU KNOW. Know that I do. Of course—you know me.

How could you doubt me.

IT IS A SHOCK—of course. We are all—we are all very—sad . . .

No! Sad is what I said. We are all—everyone who loves you—and me—especially. We are sad.

NO, WAIT. We are very happy that you are alive, Brett, and returned to us of course.

We are not sad about that, we are very happy about that.

All those months we prayed. Prayed and prayed.

And now, you are returned home to us.

And now, you are returned to us.

I KNEW YOU would return of course—I never doubted.

Even when we were out of contact—when you were in combat—I did not doubt.

In that terrible place—how do you pronounce it—“Diyala” . . .

PLEASE BELIEVE ME, darling: I love you like always.

That is why I wanted us to be engaged before you left—in case there was something that happened . . . over there.

But you know me, I am . . . I am your girl.

I am your fianc?e. Your bride-to-be.

That will not change.

EXCEPT NOW: there is so much for us to plan!

Makes my head swim so much to plan . . .

Your mother promised to help but now . . .

. . . (should not have said promised. I did not mean promised.)

But, before this, before—this . . . The surgeries, and the recovery and rehab. Before this, your mother was excited about planning the wedding, with my mother, and grandmother, and we were planning the wedding to take place as soon as you were . . .

Well yes: there is a before, and there is now.

OH IS IT WRONG to say before? And—now?

Brett why do you look at me like that . . .

Why are you angry at me . . .

Why do you seem to hate me . . .

. . . look at me like I am a stranger. And you are a stranger to me and I—I am frightened of you at such times.

BECAUSE I LOVE YOU, Brett. I love you.

I love you and so sometimes this other—it’s like this other—is staring at me out of your eyes . . .

It is very frightening to me. For I don’t know what I can do, to placate this other.

I PLEDGE TO YOU to be your loving wife forever & ever Amen.

I pledge to you as to Jesus our Savior forever & ever Amen.

I am not ashamed of loving you. Of being with you as we did . . .

I would not have been ashamed if I had been pregnant (as I had worried I might be, as you know) and I think now (almost) that I am sorry that I was not.

(Are you sorry?)

(It would be so different now!)

I feel that I am already your wife. But I feel sometimes that you are not my husband—exactly.

I feel that there is Brett my darling, and there is—this other.

Sometimes.

HERE IS THE bridal gown design.

It’s so lovely—isn’t it? Do you like it?

Please tell me yes. I am so eager to hear yes.

I know it doesn’t interest you—much. Of course . . .

Some dresses are very expensive. This is a bargain, we found online—“Bonnie Bell Designs.”

And so beautiful, I think.

Ivory silk. Ivory lace. One-shoulder neckline with a sheer lace back. The pleated bodice is “fitted” and the skirt “flared.”

The veil is gossamer chiffon. The train is three feet long.

And these are the shoes: ivory satin pumps.

Let me hold the picture to the light, maybe you can see better . . .

Do you think that I will look . . . pretty . . . in this?

You’d said I was your beautiful girl. Many times you’d said that, Brett. I believed you then, and I want to believe you now.

Please say yes.

YOU WILL WEAR your U.S. Army dress uniform. So handsome in your dress uniform with “decorations.”

You will wear the dark glasses. You will wear white gloves. The dress cap, so elegant.

Corporal Brett Kincaid. My husband.

We will practice. We have months to practice.

(YOU’D HAD A “stateside” promotion—you’d said.)

(All things have a meaning in the military—you’d said. And so stateside had a meaning but what is that meaning?—we did not know.)

(We know only that we are so proud of our Corporal Brett Kincaid.)

YOU ARE MISTAKEN—YOU do not look wounded.

You do not look “battered.”

You do not look “like shit”!

You are my handsome fianc?, you are not truly changed. There will be more surgeries. There must be time to heal, the surgeon has explained. There will be a “natural healing”—in time.

You can’t expect a miracle to be perfect!

The ears, the scalp, the forehead, the lids of the eyes. The throat beneath the jaw, on your right side. Except in bright light you would think it was an ordinary burn—burns.

Oh please don’t flinch, Brett—when I kiss you. Please.

It’s like a sliver of glass in the heart—when you push me from you.

IF PEOPLE ARE looking at you in Carthage it is only because they know of you—your medals, your honors. They are admiring of you, for you are a war hero but they would not want to intrude.

Like Daddy. He is so admiring of you, Brett!—but Daddy has a funny way about him when he’s emotional—gets very quiet—people wouldn’t believe that Zeno Mayfield is a shy man really.

Well I mean—essentially.

It’s hard for men to talk about—certain things. Daddy had not ever had a son, only daughters. To us, Daddy talks. We listen.

And Mom talks about you all the time. When you were in Iraq, in combat, she prayed for you all the time. She worried more when we didn’t hear from you than I did, almost . . .

All of my family, Brett. All of the Mayfields.

Try to believe—we love you.

I WISH YOU would come back to church with me, Brett.

Everyone is missing you there.

We have a new minister—he’s very nice.

And his wife, she’s very nice.

They ask after you every Sunday. They know about you of course.

I mean—they know that you are returned to us safely.

There are other veterans in the congregation, I think. They don’t come every week. But I think you know two of them at least—Denny Bisher and Brandon Kranach. Maybe they’d been in Iraq, or maybe Afghanistan.

Denny is in a wheelchair. Denny’s younger brother wheels him in. Or his mother. How’s Brett Denny is always asking me and I tell him you’ll contact him soon . . .

How’s Corporal Kincaid. How’s that cool dude.

No, please! Don’t be angry with me, I am sorry.

. . . I will not bring Denny up again.

. . . I will not bring church up again.

Don’t be angry at me, please I am sorry.

JUST FIREWORKS, BRETT! Over at Palisade Park.

The windows are shut. Air conditioner is on.

I can turn the music higher so you won’t hear.

I said honey—just fireworks. You know—Fourth of July in the park.

Yes better not to go this year.

I told them not to expect us—Mom and Dad. We have other things to do.

WHICH TABLETS?—the white ones, or . . .

I can bring you a glass of water.

OK, a glass of beer. But the doctor said . . .

. . . not a good idea to mix “alcohol” and “meds” . . .

Don’t—please.

WE WILL PRACTICE, in the church. Before the wedding rehearsal, we will practice.

You do not limp. Only just—sometimes—you seem to lose your balance—you make that sudden jerking movement with your legs like in a dream.

I think it is not real. It is just something in your head.

HAND-EYE COORDINATION. THEY have promised.

In the video, you can see how that boy improved.

There are many miracles. The great miracle God has provided is, you are alive and we are together.

The doctor—neurologist—says it is a matter of neuron-recircuiting.

It is a matter of new brain cells learning to take over from the damaged brain cells. It is neurogenesis.

Like not-sleeping. The brain “forgets” how to sleep. Like—sometimes—the brain forgets how to control “elimination.” It is no one’s fault.

These reflexes will come back in time, the doctor said.

WHEN THE GRENADE exploded, and the wall collapsed.

It was combat. It was in action. Which is why you have been awarded a Purple Heart.

And the Infantry Combat Badge which is a special badge beautiful gold-braided in the shape of a U with a miniature facsimile of a long-barreled rifle against a blue background. A badge to hold in the hand and contemplate like a gem.

Like a gem that is a riddle, or a riddle that is a gem.

How brave you were, from the start.

Which is why you must not feel shame, that you are returned to us.

You are not a traitor or a coward. You did not let your platoon down. You were injured, and you are convalescing. And you are in rehab.

And you will be married.

WE WILL HAVE CHILDREN, I vow. A son.

I know this. This is possible!

We will do it. We will surprise them. In rehab they have promised—the older doctor said, to me—If you love your future husband and will not give up but persevere a pregnancy is not impossible.

Lots of disabled vets have fathered children. This is well known.

The MRI did not detect any growth. The MRI did not detect any blood-clots. The MRI did not detect any “irregularities.”

Whatever you see in your head like in dreams is not real. You know this!

CORPORAL BRETT GRAHAM Kincaid.

On the maps, we tried to follow you.

Baghdad—that was the first.

Diyala Province. Sadah.

Where you were hurt—Kirkuk.

Where the maps gave out—faded.

So far from Carthage.

OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM.

Very few people in Carthage know the difference—if there is a difference—between “Iraq” and “Afghanistan.”

I know: for I am your fianc?e and it is necessary for me to know.

But still I am confused, and there is no one to ask.

For I dare not ask you.

The look in your eyes, at such times!—I feel such cold, a shudder comes over me.

He does not love me. He does not even know me.

Reverend Doig was explaining last Sunday there is no end, there can be no end, never an end to war for there is a “seed of harm” in the human soul that can never be wholly eradicated until Jesus returns to save mankind.

But when will this be?—Jesus returning to us?

Like Corporal Kincaid returning.

Yes I believe this! I want to believe this.

Must believe that there is a way of believing it—for both of us. When Reverend Doig marries us.

WHAT DID I tell them, I told them the truth—it was an accident.

I slipped and fell and struck the door—so silly.

At the ER they took an X-ray. My jaw is not dislocated.

It’s sore, it’s hard to swallow but the bruises will fade.

I know, you did not mean it.

I am sorry to upset you.

I am not crying, truly!

We will look back on this time of trial and we will say—It was a test of our love. We did not weaken.

THIS MORNING in my bed which is so lonely. Oh Brett I miss our special times together before you went away when I could come to you in your apartment and we could be alone together . . .

When that happens again, we will be happy as we were. This is not a normal way for us to be, living as we are. It’s no wonder there is strain between us. But this time will pass, this time of trial.

I wish your mother did not dislike me. When I am trying so hard to love her.

She said to me You don’t have to pretend. You can stop pretending. Any day now, you can stop pretending. And I didn’t know how to answer her—there was such dislike in her eyes . . . And finally I said But I am not pretending anything, Mrs. Kincaid! I love Brett and want only to marry him and be his wife and take care of him as he might need me, this is all I dream of.

This morning when I could not sleep after I’d wakened early—(there is a rooster somewhere behind where we live, up the hill behind the cemetery on the Post Road, I like to hear the rooster crowing but it means that the night is over and I will probably not get back to sleep)—I was remembering when we said good-bye, that last time.

In the Albany airport. And there were other soldiers arriving at the security check and some of them younger than you even. And that older officer—a lieutenant. And everyone—civilians—looking at you with respect.

So sad to kiss you good-bye! And everybody wanting to hug you and kiss you at the last minute and you were laughing saying But Julie is my fianc?e not you guys.

There are so many of us who love you, Brett. I wish you would know this.

You gave me your “special letter” then. I knew what it meant—I think I knew—I felt that I might faint—but hid it away quickly of course and never spoke of it to anyone.

I will never open it now. Now you are safely returned to us.

Yes, I still have it of course. Hidden in my room.

My sister knows of the letter—I mean, she saw it in my hand. She has no idea what is inside it. She will not ever know.

She has told me I am not worthy of you—I am “too happy”—“too shallow”—to comprehend you.

In fact Cressida knows nothing of what there is between us. No one knows, except us.

Those special times between us, Brett. We will have those special times again . . .

Cressida is a good person in her heart!—but this is not always evident.

It’s hurtful to her to observe happiness in others. Even people she loves. I think it has made a difference to her, to see you as you are now—she has been deeply affected though she would not say so.

But if you speak to her of anything personal she will stare at you coldly. Excuse me. You are utterly mistaken.

She has refused to be my maid of honor, she was scornful saying she hasn’t worn anything like a dress or a skirt since she’d been a baby and wasn’t going to start now. She laughed saying weddings are rituals in an extinct religion in which I don’t believe.

I said to Cressida What is the religion in which you do believe?

This question I put to her seriously and not sarcastically as Cressida herself speaks. For truly I wanted to know.

But Cressida had no reply. Turned away from me as if she was ashamed and did not speak.

I wish—I am praying for this!—that Cressida will come to church with us sometime. Or just with me, if you don’t want to come. I know that she has been wounded in some way, she has been hurt by someone or something, she would never confide in me. I feel that her heart is empty and yearning to be filled—to cross over.

NO, BRETT! Not ever.

You must not say such things.

We could not feel more pride for you, truly. It is a feeling beyond pride—such as you would feel for any true hero, who has acted in a way few others could act, in a time of great danger.

What you said at the going-away party, such simple words you said made everyone cry—I just want to serve my country, I want to be the very best soldier I know how to be.

This is what you have done. Please, Brett! Have faith.

The war in Iraq was the most exciting time in your life, I know. Those months you were gone from us—“deployed.” It was a dangerous time and an exciting time and (I understand) a secret time for you, we could know nothing of in Carthage.

Operation Iraqi Freedom. Those words!

We tried to follow in the news. On the Internet. We prayed for you.

Daddy would remove from the newspaper things he didn’t want me to see. Particularly the New York Times, he gets on Sundays mostly.

Photos of soldiers who have died in the war—the wars. Since 2001.

I have seen some of them of course. Couldn’t help but look for women among the rows of men looking young as boys.

There are not many female soldiers. But it is shocking to see them, their pictures with all the men.

And always smiling. Like high school girls.

In Carthage, there are some people who do not “support” the war—the wars. But they support our troops, they make that clear.

Daddy has always made that clear.

Daddy respects you. Daddy is just awkward now, he doesn’t know how to talk to you but that’s how some men are. He was never a soldier himself and has strong feelings about the Vietnam War which was the war when he was growing up. But Daddy does not mean anything personal.

You have said It’s a toss of the dice. You have said Who gives a shit who lives, who dies. A toss of the dice.

I know you don’t mean this. This is not Brett speaking but the other.

You must not despair. Life is a gift. Our lives are gifts. Our love for each other.

It was surprising, my mother is not very religious but while you were gone—she came to church with me, almost every Sunday. She prayed.

All of the congregation prayed for you. For you and the others in the war—the wars.

So many have died in the wars, it is hard for me to remember the numbers—more than one thousand?

Most of them soldiers like you, not officers. And all beloved of God, you’d wish to think.

For all are beloved of God. Even the enemy.

Just so, we must defend ourselves. A Christian must defend himself against the enemies of Christ.

This war against terror. It is a war against the enemies of Christ.

I know you did not want to kill anyone. I know you, my darling Brett, and I know this—you did not want to kill the enemy, or—anyone. But you were a soldier, this was your duty.

You were promoted because you were a good soldier. We were so proud of you then.

Your mother is proud of you, I wish she could show it better.

I wish she did not seem to blame me.

I am not sure why she would wish to blame me.

Maybe she thought I was—pregnant. Maybe she thought that was why we wanted to get married. And maybe she thought that was why you enlisted in the army—to get away.

I wish that I could speak with your mother but I—I have tried . . . I have tried and failed. Your mother does not like me.

My mother says We’ll keep trying! Mrs. Kincaid is fearful of losing her son.

I know that you don’t like me to talk about your mother—I am sorry, I will try not to. Only just sometimes, I feel so hurt.

I know, the war is a terrible thing for you to remember. When you start classes at Plattsburgh in September, or maybe—maybe it will be January—you will have other things to think about . . . By then, we will be married and things will be easier, in just one place.

I will take courses at Plattsburgh, too. I think I will. Part-time graduate school, in the M.A. in education program.

With a master’s degree I could teach high school English. I would be qualified for “administration”—Daddy thinks I should be a principal, one day.

Daddy has such plans for us! Both of us.

I WISH YOU would speak of it to me, dear Brett.

I’ve seen documentaries on TV. I think I know what it was like—in a way.

I know it was a “high” for you—I’ve heard you say to your friends. Search missions in the Iraqi homes when you didn’t know what would happen to you, or what you would do.

What you’d never say to me or to your mother you would say to Rod Halifax and “Stump”—or maybe you would say it to a stranger you met in a bar.

Another vet, you would speak with. Someone who didn’t know Corporal Brett Kincaid as he’d used to be.

There is no “high” like that in Carthage. Tossing your life like dice.

Our lives since high school—it’s like looking through the wrong end of a telescope, I guess—so small.

Those sad little cardboard houses beneath a Christmas tree, houses and a church and fake snow like frosting. Small.

EVEN OUR WOUNDS here are small.

IN CARTHAGE, your life is waiting for you. It is not a thrilling life like the other. It is not a life to serve Democracy like the other. You said such a strange thing when you saw us waiting for you by the baggage claim, we were thrilled you were walking unassisted and this look came in your face I had not ever seen before and it was like you were afraid of us for just a moment you said Oh Christ are you all still alive? I was thinking you were all dead. I’d been to the other place, and I saw you all there.

THREE (#ulink_0f00dfe3-ceb3-5710-89e7-99cfb39c1604)

The Father (#ulink_0f00dfe3-ceb3-5710-89e7-99cfb39c1604)

OH DADDY WHY’D YOU call me such a name—Cressida.

Because it’s an unusual name, honey. And it’s a beautiful name.

FIRE SHONE INTO the father’s face. His eyes were sockets of fire.

He hadn’t the strength to open his eyes. Or the courage.

The doe’s torso had been torn open, its bloody interior crawling with flies, maggots. Yet the eyes were still beautiful—“doe’s eyes.”

He’d seen his daughter there, on the ground. He was certain.

The sick-sliding sensation in his gut wasn’t unfamiliar. In that place, again. The place of dread, horror. Guilt. His fault.

And how: how was it his fault?

Lying on his back and his arms flung wide across the bed—(he remembered now: they’d brought him home, to his deep mortification and shame)—that sagged beneath his weight. (Last time he’d weighed himself he’d been, dear Christ, 212 pounds. Heavy and graceless as wet cement.)

A memory came to him of a long-ago trampoline in a neighbor’s backyard when he’d been a child. Throwing himself down onto the coarse taut canvas that he might be sprung into the air—clumsily, thrillingly—flying up, losing his balance and falling back, flat on his back and arms sprung, the breath knocked out of him.

On the trampoline, Zeno had been the most reckless of kids. Other boys had to marvel at him.

Years later when his own kids were young it had become common knowledge that trampolines are dangerous for children. You can break your neck, or your back—you can fall into the springs and slice yourself. But if he’d known, as a kid, Zeno wouldn’t have cared—it was a risk worth taking.

Nothing in his childhood had been so magical as springing up from the trampoline—up, up—arms outflung like the wings of a bird.

Now, he’d come to earth. Hard.

HE’D TOLD THEM like hell he was going to any hospital.

Fucking hell he was not going to any ER.

Not while his daughter was missing. Not until he’d brought her back safely home.

He’d allowed them to help him. Weak-kneed and dazed by exhaustion he hadn’t any choice. Falling on his knees on sharp rocks—a God-damned stupid thing to have done. He’d been pushing himself in the search, as his wife had begged him not to do, as others, seeing his flushed face and hearing his labored breath, had urged him not to do; for by Sunday afternoon there must have been at least fifty rescue workers and volunteers spread out in the Preserve, fanning in concentric circles from the Nautauga River at Sandhill Point where it was believed the missing girl had been last seen.

It was the father’s pride, he couldn’t bear to think that his daughter might be found by someone else. Cressida’s first glimpse of a rescuer’s face should be his face.

Her first words—Daddy! Thank God.

HE’D HAD SOME “heart pains”—(guessed that was what they were: quick darting pains like electric shocks in his chest and a clammy sensation on his skin)—a few times, nothing serious, he was sure. He hadn’t wanted to worry his wife.

A woman’s love can be a burden. She is desperate to keep you alive, she values your life more than you can possibly.

What he most dreaded: not being able to protect them.

His wife, his daughters.

Strange how when he’d been younger, he hadn’t worried much. He’d taken it for granted that he would live—well, forever! A long time, anyway.

Even when he’d received death threats over the issue of Roger Cassidy—defending the “atheist” high school biology teacher when the school board had fired him.

He’d laughed at the threats. He’d told Arlette it was just to scare him and he certainly wasn’t going to be scared.

Just last month his doctor Rick Llewellyn had examined him pretty thoroughly in his office. And an EKG. No “imminent” problem with his heart but Zeno’s blood pressure was still high even with medication: 150 over 90.

Blood pressure, cholesterol. Fact is, Zeno should lose twenty pounds at least.

On the bed he’d tried to untie and kick off the heavy hiking boots but there came Arlette to pull them off for him.

“Lie still. Try to rest. If you can’t sleep for Christ’s sake, Zeno—shut your eyes at least.”

She was terrified of course. Fussing and fuming over him to deflect her thoughts from the other.

That morning at about 4 A.M. she’d wakened him. When she’d discovered that Cressida hadn’t come home. Since that minute he’d been awake in a way he was rarely awake—all of his senses alert, to the point of pain. Stark-staring awake, as if his eyelids had been removed.

A search. A search for his daughter. A search that was for a missing girl.

These searches of which you hear, occasionally. Often for a lost child.

A kidnapped child. Abducted.

You hear, and you feel a tug of sympathy—but not much more. For your life doesn’t overlap with the lives of strangers and their terror can’t be shared with you.

Was he awake? Or asleep? He saw the steeply hilly forest strewn with enormous boulders as in an ancient cataclysm and from behind one of these a girl’s uplifted hand, arm—a glimpse of a naked shoulder which he knew to be badly bruised . . . Oh Daddy where are you. Dad-dy.

“Lie still. Please. If something happens to you at such a time . . . ”

The voice wasn’t Cressida’s voice. Somehow, Arlette had intervened.

He knew, his wife didn’t trust him. Married for more than a quarter of a century—Arlette trusted Zeno less readily than she’d done at the start.

For now she knew him, to a degree. To know some men is certainly not to trust them.

She was breathless, irritated. Not terrified—not so you’d see—but irritated. The house was crowded with well-intentioned relatives. There were police officers coming and going—their ugly police-radios crackling and squawking like demented geese. There were reporters for local media eager for interviews—they were not to be turned away, for they would be useful. And photos of Cressida had to be supplied, of course.

Coffee? Iced tea? Grapefruit juice, pomegranate juice? With a grim sort of hostess-gaiety Arlette offered her visitors refreshments, for she knew no other way to deal with people in her house.

Somehow, before she’d had a chance to call her sister Katie Hewett, Katie had come to the house. This was by 10 A.M. Katie had taken over the hostess-role and was helping Arlette answer phones—family phone, cell phones—which rang frequently and with each call, despite the evidence of the caller ID, there was the hope that the next voice they heard would be Cressida’s.

Hi there! Gosh! I just saw on TV that I’m “missing”. . .

Wow. Sorry. Oh God you won’t believe what happened but I’m OK now . . .

Except the voice was never Cressida’s. Remarkable, how it was never Cressida’s.

Years ago Arlette would have crawled beside her husband in their bed, in a crisis like this; she would not have minded that her husband had sweated through his clothes, T-shirt and khaki shorts that were now clammy-cool, and smelled of his body; she would have held the anguished man in her arms, to shield him. And Zeno would have gathered his wife in his arms, to shield her. Shivering and shuddering and dazed with exhaustion but together in this terrible time.

Now, Arlette tugged at his hiking boots—so heavy! And the laces needing to be untied. Pulled the boots off his enormous feet seeing that, even in the rush of preparing to leave for the Nautauga Preserve, he’d remembered to put on a double pair of socks—white liner socks, light-woolen socks.

For all his careless-seeming ways, Zeno was a meticulous man. A conscientious man. The only mayor of Carthage in recent decades who’d left office—after eight years, in the 1990s—with a considerable surplus in the city treasury, and not a gaping deficit. (Of course, it was a quasi-secret that Mayor Mayfield had written personal checks for a number of endangered projects—parks and recreation maintenance, Little League softball, the Black River Community Walk-In Clinic.) One of the few mayors in all of upstate New York who, as he’d liked to joke, hadn’t even been investigated, let alone indicted, tried and convicted, for malfeasance in office.

Arlette had asked the young man who’d driven Zeno home in Zeno’s Land Rover what had happened to him in the Preserve, for she knew that Zeno would never tell her the truth.

He’d said, Zeno had gotten overheated. Over-tired. Dehydrated.

He’d said this was why it isn’t a good idea, a family member to be searching for someone in his family who’s been reported lost.

Zeno smiled a ghastly smile. Zeno managed to speak, for Zeno must always have the last word.

OK, he’d try to sleep. A nap for an hour maybe.

Then, he intended to return to the Preserve.

“She can’t be there a second night. We can’t—that can’t—happen.”

He stumbled on the stairs. Didn’t hear Katie speak to him, and didn’t seem to register that WCTG-TV was coming to the house to do an interview with the parents of the missing girl for the Sunday 6 P.M. news, later that afternoon.

Arlette had accompanied Zeno upstairs trying unobtrusively to slip her arm around his waist, but he’d pushed from her with a little snort of indignation.

He’d needed to use the bathroom, he said. Needed some privacy.

“I’m not going to croak in here, hon—I promise.”

This was meant to be humor. Just the word croak.

She’d made a sound like laughter, or the hissing rejoinder to laughter, and turned away, and left the man to his privacy.

Almost, they were adversaries now. Grappling together each knowing what must be done, what should be done, annoyed with the other for being blind, stubborn.

Arlette had known he’d become overheated in the Preserve, he’d had no right to rush off like that tramping through underbrush while she was alone at the house. Waiting for a call—calls. Waiting for something to happen.

After a distracted hour she returned to check on Zeno: he was sprawled on the bed only partly undressed. As if he’d been too exhausted to do more than pull off his khaki shorts and let them fall to the floor.

Sprawled, breathing hoarsely and wetly, through his mouth, like a beached whale might breathe. And his face slack putty-colored, you’d never have guessed had been a handsome face not so long ago.

Unshaven. Wiry whiskers sprouting on his jaws.

Zeno Mayfield was a man who had to be prevented from pushing himself too hard. As if he had no natural sense of restraint, of normal limits.

As, when he’d been a young attorney taking on difficult cases—hopeless cases—unpopular cases; once, unforgivably, taking on a case so controversial, anonymous callers had threatened him and his family and Arlette had worried that some madman might mail a bomb, or affix a bomb to one of their cars. In the name of God think what you are doing, man—one of the anonymous notes had warned.

All Zeno had done, he’d protested, was defend a high school biology teacher who’d been suspended from his job for having taught Darwinian evolutionary theory to the exclusion of “creationism.”

And when he’d been mayor of Carthage, an exhausting and quixotic venture into “public service” that had paid a token salary—(fifteen hundred annually!)—he’d pushed himself beyond what even his avid supporters might have expected of him and saw his popularity plummet nonetheless. The most controversial issue of Zeno’s mayoralty had been a campaign to install recycling in Carthage—yellow barrels for bottles and cans, green barrels for paper and cardboard. You’d have thought that Zeno Mayfield was a descendant of Trotsky! His daughters had asked plaintively Why do people hate Daddy? Don’t they know how funny and nice Daddy is?

Arlette hadn’t lain down beside him. She hadn’t held him tight in her arms. But she’d laid a cloth over his face, dampened with cold water, and he’d pushed it off and clutched anxiously at her hand.

“Lettie—d’you think—he did something to her? And now he’s ashamed, and can’t tell us? Lettie—d’you think—oh God, Lettie . . . ”

YOUR MOTHER AND I chose our daughters’ names with particular care. Because we don’t think that either of you is ordinary. So an ordinary name isn’t appropriate.

He was solemn and dogged trying to explain. She was younger than the age she was now and rudely she laughed.

Bullshit, Daddy. That is such bullshit.

It was like Cressida to laugh in your face. Squinch up her face like a wicked little monkey. Her laughter was high-pitched like a monkey’s chittering and her small shiny-black eyes were merry with derision.

They were in someplace Zeno didn’t recognize. Not in the forest now but in a place meant to be this place—the Mayfield home.

Why is it, when you dream about a place meant to be “home”—or any “familiar” place—it never looks like anything you’d ever seen before?

He was trying to explain to her. She was making her silly-little-girl face rolling her eyes and batting away his words as she’d have batted away badminton birdies with both her balled-up fists.

Saying Bullshit Daddy, except for her face Juliet is O-R-D-I-N-A-R-Y.

Zeno took exception to this. Zeno was angered when his bright unruly younger daughter mocked his sweetly-serene and beautiful elder daughter.

And anyway it wasn’t true. Or it was a partial truth. For Juliet’s beauty wasn’t exclusively her face.

The exchange between the father and Cressida was a dream. Yet, the exchange had taken place more or less in this way, years before.

The Mayfield girls were like the daughters of a fairy-tale king.

Bitterly the younger daughter resented the fact—(if it was a fact, it was unprovable)—that the father loved the elder, more beautiful daughter more than he loved her, whose twisty little heart he couldn’t master.

I love both our girls. I love them for different reasons. But equally.

And Arlette said I hope you do. And if you don’t, or can’t—I hope you can disguise it.

All parents know: there are children who are easy to love, and children who are a challenge to love.

There are radiant children like Juliet Mayfield. Guileless, shadowless, happy.

There are difficult children like Cressida. Steeped in the ink of irony as if in the womb.

The bright happy children are grateful for your love. The dark twisty children must test your love.

Maybe Cressida was “autistic”—in grade school, the possibility had been raised.

Later, in high school the fancier epithet “Asperger’s” was suggested—with no more validation.

If Cressida had known she’d have said, airily—Who cares? People are such idiots.

Zeno supposed that in secret, Cressida cared very much.

It was clear that Cressida resented how in Carthage, among people who knew the Mayfields, she was likely to be described as the smart one while her sister Juliet was the pretty one.

How much would an adolescent girl rather be pretty, than smart!

For of course, Cressida was invariably judged too smart.

As in too smart for her own good.

As in too smart for a girl her age.

When she’d first started school, she’d complained: “Nobody else is named ‘Cressida.’ ”

It was a difficult name to pronounce. It was a name that fitted awkwardly in the mouth.

Her parents had said of course no one else was named “Cressida” because “Cressida” was her own special name.

Cressida had considered this. She did think of herself as different from other children—more restless, more impatient, more easily vexed, smarter—(at least usually)—quicker to laugh and quicker to tears. But she wasn’t sure if having a special name was a good idea, for it allowed others to know what might be better kept secret.

“I hate it when people laugh at me. I hate it if they call me ‘Cress’—‘Cressie.’ ”

She was one of those individuals, less frequently female than male, whose names couldn’t be appropriated—like a Richard who refuses to be diminished to “Dick,” or a Robert who will not be “Bob.”

When she was older and may have felt a little (secret) pride in her unusual name, still she sometimes complained that other people asked her about it; for other people, including teachers, were likely to be over-curious, or just rude: “ ‘Cressida’ makes me feel self-conscious, sometimes.”

Or, with a downward tug of her mouth, as if an invisible hook had snagged her there, “ ‘Cressida’ makes me feel accursed.”

Accursed! This was not so remarkable a word for Cressida, as a girl of twelve who loved to read in the adult section of the Carthage Public Library, particularly novels designated as dark fantasy, romance.

Of course, Cressida had looked up her name online.

Reporting to her parents, incensed: “ ‘Cressida’—or ‘Criseyde’—isn’t nice at all. She’s ‘faithless’—that’s how people thought of her in the Middle Ages. Chaucer wrote about her, and then Shakespeare. First she was in love with a soldier named Troilus—then she was in love with another man—and when that ended, she had no one. And no one loved her, or cared about her—that was Cressida’s fate.”

“Oh, honey, come on. We don’t believe in ‘fate’ in the U.S. of A. in 1996—this ain’t the Middle Ages.”

It was the father’s prerogative to make jokes. The daughter twisted her mouth in a wounded little smile.

The previous fall when Cressida was a freshman at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, she reported back that one of her professors had remarked upon her name, saying she was the “first Cressida” he’d ever encountered. He’d seemed impressed, she said. He’d asked if she’d been named for the medieval Cressida and she’d said, “Oh you’ll have to ask my father, he’s the one in our family with delusions of grandeur.”

Delusions of grandeur! Zeno had laughed but the remark carelessly flung out by his young daughter had stung.

AND ALL THIS while his daughter is awaiting him.

His daughter with black-shining eyes. His daughter who (he believes) adores him and would never deceive him.

“Maybe she’s returned to Canton. Without telling us.”

“Maybe she’s hiding in the Preserve. In one of her ‘moods’ . . .”

“Maybe someone got her to drink—got her drunk. Maybe she’s ashamed . . .”

“Maybe it’s a game they’re playing. Cressida and Brett.”

“A game?”

“ . . . to make Juliet jealous. To make Juliet regret she broke the engagement.”

“Canton. What on earth are you saying?”

They looked at each other in dismay. Madness swirled in the air between them palpable as the electricity before a storm.

“Jesus. No. Of course she hasn’t ‘returned’ to Canton—she was deeply unhappy in Canton. She doesn’t have a residence in Canton. That’s insane.” Zeno wiped his face with the damp cloth Arlette had brought him earlier, that he’d flung aside onto the bed.

Arlette said: “And she and Brett wouldn’t be ‘playing a game’ together—that’s ridiculous. They scarcely know each other. And I don’t think that Juliet was the one to break the engagement.”

Zeno stared at his wife. “You think it was Brett? He broke the engagement?”

“If Juliet broke it, it wasn’t her choice. Not Juliet.”

“Lettie, did she tell you this?”

“She hasn’t told me anything.”

“That son of a bitch! He broke the engagement—you think?”

“He may have felt that Juliet wanted to end it. He may have felt—it was the right thing to do.”

Arlette meant: the right thing to do considering that Kincaid was now a disabled person at twenty-six.

Not so visibly disabled as some Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans in Carthage, except for the skin-grafts on his head and face. His brain had not been seriously injured—so it was believed. And Juliet had reported eagerly that doctors at the VA hospital in Watertown were saying that Brett’s prognosis, with rehab, was “good”—“very good.”

Before dropping out impulsively, after 9/11, to enlist in the U.S. Army with several friends from high school, Brett had taken courses in finance, marketing, and business administration at the State University at Plattsburgh. Zeno had the idea that the kid hadn’t been highly motivated—as Kincaid’s prospective father-in-law, he had some interest in the practical side of his daughter’s romance, though he didn’t think he was a cynic: just a responsible dad.

(Juliet would never forgive him if she’d known that Zeno had managed to see Brett Kincaid’s transcript for the single semester he’d completed at SUNY Plattsburgh: B’s, B+. Maybe it was unfair but Christ, Zeno Mayfield wanted for his beautiful daughter a man just slightly better than a B+ at Plattsburgh State.)

He’d tried—hard!—not to think of Brett Kincaid making love to his daughter. His daughter.

Arlette had chided him not to be ridiculous. Not to be proprietary.

“Juliet isn’t ‘yours’ any more than she’s mine. Try to be grateful that she’s so happy—she’s in love.”

But that was what disturbed the father—his firstborn daughter, his sweet honeybunch Juliet, was clearly in love.

Not with Daddy but with a young rival. Good-looking and with the unconscious swagger of a high school athlete accustomed to success, applause. Accustomed to the adoration of his peers and to the admiration of adults.

Accustomed to girls: sex. Zeno felt a wave of purely sexual jealousy. Nothing so upset him as glimpsing, by chance, his daughter and her tall handsome fianc? kissing, slipping their arms around each other’s waist, whispering, laughing together—so clearly intimate, and comfortable in their intimacy.

That is, before Brett Kincaid had been shipped to Iraq.

Initially Zeno had wanted to think that the kid had had too easy a time, cutting a swath through the Carthage high school world with an ease that couldn’t prepare him for the starker adult world to come. But that was unfair, maybe: Brett had worked at part-time jobs through high school—his mother was a divorc?e, with a low-paying job in County Services at the Beechum County Courthouse—and he was, as Juliet claimed, a “serious, committed Christian.”

It was hard to believe that any teenaged boys in Carthage were “Christians”—yet, this seemed to be the case. When Zeno had been active in the Carthage Chamber of Commerce he’d encountered kids like these, frequently. Girls like Juliet hadn’t surprised him—you expected girls to be religious. In a girl, religious can be sexy.

In a boy like Brett Kincaid it seemed like something else. Zeno wasn’t sure what.

Recalling how Brett had said, at the going-away party for him and his high school friends, each enlisted in the U.S. Army and each scheduled for basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, that he wanted to be the “best soldier” he knew how to be. (His own father had “served” in the first Gulf War.) Winter/spring 2002 had been an era of patriotic fervor, following the terrorist attack at the World Trade Center the previous September; it had not been an era in which individuals were thinking clearly, still less young men like Brett Kincaid who seemed truly to want to defend their country against its enemies. How earnestly Brett had spoken, and how handsome he’d been in his U.S. Army dress uniform! Zeno had stared at the boy, and at his dear daughter Juliet in the crook of the boy’s arm. His heart had clenched in disdain and dread as he’d thought Oh Jesus. Watch out for this poor sweet dumb kid.

And now recalling that poignant moment, when everyone in the room had burst into applause, and Juliet’s face had shone with tears, Zeno thought Poor bastard. It’s a cruel price you pay for being stupid.

Difficult for Zeno Mayfield who’d come of age in the late, cynical years of the Vietnam War to comprehend why any intelligent young person like Brett Kincaid would willingly enlist in the military. Why, when there was no draft! It was madness.

Wanting to “serve” the country—whose country? Virtually no political leaders’ sons and daughters enlisted in the armed services. No college-educated young people. Already in 2002 you could figure that the war would be fought by an American underclass, overseen by the Defense Department.

Yet Zeno hadn’t spoken with Brett on this subject. He knew that Juliet didn’t want him to “intrude”—Zeno had such ideas, such plans, for everyone in his orbit, he had to make it a principle to keep clear. And he hadn’t felt close enough to the boy—there was an awkwardness between them, a shyness in Brett Kincaid as he shook hands with Zeno Mayfield, his prospective father-in-law, he’d never quite overcome.

Often, Brett had called him “Mr. Mayfield”—“sir.”

And Zeno had said to call him “Zeno” please—“We’re not on the army base.”

Zeno had laughed, made a joke of it. But it disturbed him, essentially. His prospective son-in-law was uneasy in his presence which meant he didn’t like Zeno.

Or maybe, didn’t trust Zeno.

In the matter of the military, for instance. Though Zeno hadn’t tried to talk him out of enlisting, Zeno hadn’t made a point of congratulating him, either, as everyone else was doing.

Serve my country. Best soldier I can be.

Like my dad . . .

There was a father, evidently. An absent father. A soldier-father who’d disappeared from Carthage twenty years before.

Brett had been brought up some kind of Protestant Christian—Methodist, maybe. He wasn’t critical, questioning. He wasn’t skeptical. He wanted to believe, and so he wanted to serve.

Chain of command: you obeyed your superior officer’s orders as he obeyed his superior officer’s orders as he obeyed his superior officer’s orders and so to the very top: the Administration that had declared war on terror and beyond that Administration, the militant Christian God.

None of this was questioned. Zeno wouldn’t have wished to stir doubt. He’d defended the high school biology teacher Cassidy who’d taught Darwinian evolutionary theory to the exclusion of “creationism”—more specifically, Cassidy had ridiculed “creationism” in the classroom and deeply offended some students—and their parents—who were evangelical Christians; Zeno had defended Cassidy against the Carthage school board, and had won his case, but it had been a Pyrrhic victory, for Cassidy had no professional future in Carthage and had been soundly disliked for his “arrogant, atheistic” stance. And Zeno Mayfield had suffered a good deal of abuse, too.

Except that Brett Kincaid had become engaged to his daughter Juliet, Zeno had no wish to enlighten the boy. You had to learn to live with religion, if you had a public career. You had to know when to be quiet about your own skepticism.

Juliet belonged to the Carthage Congregationalist Church: she’d made a decision to join when she was in high school, drawn to the church by a close friend; after she and Brett began seeing each other, Brett accompanied her to Sunday services. No one else in the Mayfield family attended church. Arlette described herself as “a mild kind of Protestant-Christian-Democrat” and Zeno had learned to parlay questions about faith by saying he was a “Deist”—“In the hallowed tradition of our American Founding Fathers.” Zeno found serious talk of religion embarrassing: revealing what you “believed” was a kind of self-exposure not unlike stripping in public; you were likely to reveal far more than you wished. Cressida bluntly dismissed religion as a pastime for “weak-minded” people—she’d gone to church with her older sister for a few months when she’d been in middle school, and been bored silly.

Strange how Cressida could be right about so much, and yet—(this was not a thought Zeno allowed himself to express aloud)—you resented her remarks, and were inclined to dislike her for making them.

Juliet’s Christian faith had certainly been a great solace to her, since news had come of her fianc?’s injuries—a hurried and incoherent phone message from Brett’s mother had been the first they’d heard; she’d been grateful, and never ceased proclaiming her gratitude, that Brett hadn’t been killed; that God had “spared him.”

The shock to Juliet had been so great, Zeno thought, she hadn’t altogether absorbed the fact that her fianc? was a terribly changed man—and the changes weren’t likely to be exclusively physical.

Since Brett had returned to Carthage, and was living in his mother’s house about three miles from the Mayfields, Juliet had spent a good deal of time with him there; the elder Mayfields hadn’t seen much of him. When she could, Juliet accompanied Brett to the rehab clinic attached to the Carthage hospital; she attended some of his counseling sessions, as his fianc?e; eagerly she reported back to her parents that as soon as he was better able to concentrate Brett intended to re-enroll at Plattsburgh and get a degree in business and that there was talk—(how substantial, Zeno didn’t know)—of Brett being hired by a Carthage businessman who made it a point to hire veterans.

See, Daddy—Brett has a future!

Though I know you want me to dump him. I will not.

Zeno would have protested, if Juliet had so accused him.

But, of course, Juliet had not.

Beautiful Juliet never accused anyone of such low thoughts. Least of all her father whom she adored.

But there came impish Cressida to slip her arm through Daddy’s arm and to tug at him, to murmur in his ear in her scratchy voice, “Poor Julie! Not the ‘war hero’ she’d expected, is he.” Cruel Cressida squirming with something like stifled laughter.

Zeno had said reprovingly, “Your sister loves Brett. That’s the main thing.”

Cressida snorted with laughter like a mischievous little girl.

“It is?”

Several nights later, on the Fourth of July, Juliet had returned home early—and alone—(the most gorgeous, gaudy fireworks had just begun exploding in the sky above Palisade Park)—to inform her family that the engagement was ended.

Her cheeks were tear-streaked. Her face had lost its luminosity and looked almost plain. Her voice was a hoarse whisper.

“We’ve both decided. It’s for the best. We love each other, but—it’s ended.”

Zeno and Arlette had been astounded. Zeno had felt a sick sinking sensation in his gut. For this was what he’d wanted—wasn’t it? His beautiful daughter spared a life with a handicapped and embittered husband?

When Arlette moved to embrace her, Juliet pushed past her with a choked little sob and hurried up the stairs and shut her bedroom door.

Even Cressida had been shocked. For once, her shiny black eyes hadn’t danced with derision when the subject of Juliet and Brett Kincaid came up—“Oh God! Julie will be so unhappy.”

At twenty-two, Juliet was still living at home. She’d gone to college in Oneida but had wanted to return to Carthage to teach (sixth grade) at the Convent Street School a few miles away from the family home on Cumberland Avenue. Planning her wedding to Corporal Brett Kincaid—guest list, caterer, bridal gown and bridesmaids, music, flowers, wedding service at the Congregationalist Church—had been the consuming passion of her life for the past eighteen months, and now that the engagement had ended Juliet seemed scarcely capable of speech apart from the most perfunctory exchanges with her family.

Though Juliet was always unfailingly courteous, and sweet. Tears welling in her eyes at which she brushed with her fingertips, as if apologetically.

There’d been no reproach in her manner, when the father gazed at her searchingly, waiting for her to speak. For never had Juliet so much as hinted Are you happy, Daddy? I hope you are happy, Brett is out of our lives.

Numbly Zeno said to Arlette: “She hasn’t spoken to you—yet? She hasn’t wanted to talk about it?”

“No.”

“What about Cressida?”

“No. Juliet would never discuss Brett with her.”

In the issue of the sisters, it had often been that Arlette clearly sided with the pretty one and not the smart one.

“Maybe Brett wanted to talk about it with Cressida. Maybe that was why—the reason—they were together last night . . .”

If truly they’d been together—alone together. Zeno had to wonder if that was true.