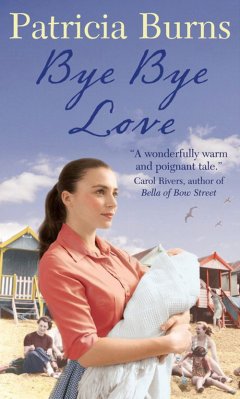

Bye Bye Love

Àâòîð:Patricia Burns

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:247.84 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 255

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 247.84 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Bye Bye Love

Patricia Burns

It’s 1953, Coronation Year and everybody is celebrating… Everybody it seems, except Scarlett Smith. In one day, she loses her Mum and her home as well. Now she and her father are adrift in Southend, moving from one grimy rented room to the next – the only happiness for Scarlett is her innocent romance with local boy Tom.Scarlett’s once-loving Dad can’t hold down a job – or keep off the drink. Scarlett must leave school to work in a factory, just as Tom heads off to do national service. With Tom away, Scarlett’s life is bleak, with the only highlight being the dance hall on a Saturday night.There Scarlett forgets her troubles with the lead singer of a rock ,n’ roll band – with disastrous consequences…Praise for Patricia Burns“The characters spring to life and simply walk off the page. ” Sally WorboyesOther books by Patricia BurnsWe'll Meet AgainFollow Your Dream

Patricia Burns is an Essex girl born and bred and proud of it. She spent her childhood messing about in boats, then tried a number of jobs before training to be a teacher. She married and had three children, all of whom are now grown up, and she recently became a grandmother. She is now married for the second time and is doing all the things she never had time for earlier in life.

When not busy writing, Patricia enjoys travelling and socialising, walking in the countryside round the village where she now lives, belly dancing and making exotic costumes to dance in.

Find out more about Patricia at www.mirabooks. co.uk/patriciaburns

Bye Bye Love

Patricia Burns

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To Isadora,

who carries our love into the future

CHAPTER ONE

IT WAS going to be a very special day. Not that there were any clues to it when Scarlett Smith woke up. Everything seemed much the same. There was the sound of her mother’s broom knocking against the skirting-boards as she swept the floors downstairs, there was the drone of a BBC accent coming from the wireless and there was the familiar smell, the one that Scarlett had grown up with, the smell of stale beer and cigarette ash. The morning smell of a pub.

But today was June the second. Coronation Day. The Queen was going to be crowned Elizabeth II of England and it was going to be extremely busy at the Red Lion. Scarlett slid out of bed, washed in cold water, pulled on an old cotton dress and a cardigan and ran down the creaking stairs to the lounge bar. Joan Smith, a floral overall wrapped round her cosy body, was mopping the floor. She looked up with a smile.

‘How’s my darling girl this fine morning? Not that it is fine. It’s raining. Such a pity! And all those people sleeping out on the pavements in London to get a look at the Queen. It said on the news they was out in their thousands. Old people. Little kiddies. But they’re all in great spirits, they said. Ready to cheer and wave their Union Jacks.’

‘Must be wonderful to be up in London,’ Scarlett said.

‘Yes—a once in a lifetime event. The fairy tale princess becomes queen.’ Her mother sighed. She leaned on the handle of her mop, a faraway expression in her eyes. Joan Smith loved a good story. A real life one featuring a real live queen was even better. Then she snapped out of it. ‘Still, we’re going to have a right old knees-up here, aren’t we? Morris dancers, tea on the village green—mind you, it might be in the village hall at this rate—and us open all day so as people can toast Her Majesty. No peace for the wicked! Come on, sweetheart, fetch a bucket and cloth and do the bars and tables for us. Sooner we finish, sooner we can have breakfast. I got fresh eggs. Old Harry brought us in a basin last night.’

Mother and daughter worked rapidly through the lounge and public bars, wiping, polishing, setting out clean ashtrays, fresh beer mats and bar towels, straightening the tables and stools. Nobody looking on would have guessed they were related. Joan was round and dumpy, her brown hair greying, her blue eyes fading, her hands cracked and swollen and knees stiff from a lifetime of hard work. Scarlett, at fourteen, was already taller than her mother, slim and strong with big brown eyes and long dark hair pulled back in a shiny ponytail, her coltish figure starting to develop into a woman’s body.

‘Don’t it look lovely?’ Joan said as they gave a last rub to the horse brasses on the beams.

‘Very patriotic,’ Scarlett agreed.

The Red Lion was all dressed up for the Coronation. Outside there was red, white and blue bunting draped from the windows and over the sign, with a big Union Jack over the door, and inside more Union Jacks and flags from the countries of the great British Empire were hung around the bars. Pictures of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh and the little prince and princess had been cut out of magazines, framed with red, white and blue ribbons and stuck up on any available wall space. A specially brewed Coronation Ale had been delivered from the brewery a few days ago and was nicely settled and ready to serve to any of Her Majesty’s loyal subjects who cared to drink her health. Nobody could say the Smiths hadn’t made an effort.

The two put away the cleaning things and Joan set about making breakfast in the kitchen-cum-living room behind the public area. It was rather a dark room, tacked onto the back of the main building and crowded with a table and chairs, sink and stove and dresser, and a sitting area of two Windsor chairs and a small fireside chair grouped round the fireplace. The big brown wireless set sat in pride of place on a small table next to the larger of the Windsor chairs. When Scarlett was little, the grouping reminded her of the Three Bears, and she would always be ready to guard her breakfast porridge against invasions of golden-haired thieves.

Joan poured tea into a large white cup, put in three sugars, stirred it and handed it to Scarlett.

‘Go up and give your dad his cuppa, lovey.’

Scarlett walked carefully up the stairs. Her dad never made an appearance until half an hour or so before opening time, giving himself just enough time to check the beers, have a cigarette and look at the sports page of the newspaper before the first customers of the day came in. Scarlett tapped on the door of her parents’ bedroom, listened for the muffled reply from inside and went in. The curtains were still closed and the air smelt of beer fumes. Her father had had a hard night last night. The regulars had been getting in some practice at toasting the new queen and naturally the landlord had to keep them company.

Victor Smith raised his head from the pillow as his daughter came in.

‘Ah—tea—what a lovely girl you are.’

He coughed, fumbled for his cigarettes and matches, lit up the first Player’s Navy Cut of the day and took a deep drag.

‘That’s better. Tell your mum I’ll be down soon.’

Scarlett raised her eyebrows at this.

‘Pull the other one, Dad.’

They both knew that pigs would fly and the moon turn blue before Victor made it to breakfast.

Victor laughed, coughed and patted her arm.

‘You’re getting too knowing by half, you are. Sharp as a barrowload of monkeys. What’s two pints of best, a rum and black and a half of mild and bitter?’

Scarlett added them up in her head in a trice, then made up a longer round for him to calculate. It was a game they had played practically since she could count. As a result she was top of her class at mental arithmetic.

‘Can’t beat you these days,’ Victor admitted.

Scarlett kissed the top of his head, left him to his tea and cigarette and went back to the kitchen.

‘He all right?’ her mother asked, whipping eggs out of the frying pan and slipping them onto a plate.

‘’Course,’ Scarlett said.

When she was younger, she had accepted the idea that fathers lay in bed while mothers worked. Even when she’d realised that other fathers got up and cycled to farms and factories to start work at eight, or down to the station to catch a train up to London and start work at nine, she’d still accepted it because, as her mother pointed out, other fathers didn’t have to stand behind a bar each evening. But as she’d grown older she’d realised that it was her mother who served the drinks, cleared the glasses, changed the optics, emptied the ashtrays and washed up. Her father supervised. That involved leaning on the bar, chatting to the customers and sampling the stock.

‘Oh, but he has all the cellar work to do,’ her mother said when Scarlett questioned this. ‘Everybody says he serves the best pint for miles around.’

Which was true. The Red Lion and Victor Smith were famous for their beers, and he was known as a good landlord who made everyone feel at home but dealt quickly with any potential trouble. And though other dads might work harder than hers, none of them were more fun, or quicker to back you up when you needed it. All the same, she couldn’t help thinking that it would have been nice to have a bit more help today.

‘Here you are, poppet.’

Joan placed a blue and white striped plate in front of her. On it were piled two chunky slices of fried bread, a rasher of bacon and two large fried eggs, the whites crispy around the edges, just the way she liked them.

Scarlett sat down at the rickety table with its checked yellow oilcloth cover.

‘Two eggs?’ she questioned.

‘Well—we need to keep our strength up,’ her mother said, but she only managed to work her way through one egg herself before she pushed her plate to one side and sat holding her teacup and staring at its contents.

Scarlett looked at her. Anxiety stirred within her.

‘What’s the matter, Mum? You all right?’

‘Yes, yes, quite all right.’

‘You ain’t eaten your breakfast.’

Her mother never left food on her plate. It was a waste. After years of wartime rationing, nobody ever wasted a crumb.

‘I will. In a minute.’

Joan’s hands were shaking. She put the teacup down.

‘Mum? You’ve gone all pale.’

‘It’s all right. I’m fine. Just a touch of heartburn, that’s all. Go and fetch me the Milk of Magnesia, there’s a good girl.’

Scarlett ran to the corner cupboard and got out the blue bottle. She gave it a good shake and poured the thick white liquid into a spoon. Her mother swallowed it down.

‘That’s it. That’ll do the trick.’

But still she pushed her plate towards Scarlett.

‘You finish it off for me, darling. Go on, before it gets cold.’

Scarlett did as she was told, though worry made it difficult to eat.

‘P’raps you ought to go to the doctor, Mum.’

‘Oh, doctors—I know what he’ll say if I do. Take a tonic and get some rest. Rest! Who’s going to do my work if I rest, that’s what I’d like to know.’

‘I could, if you’d let me.’

Joan patted her hand.

‘That’s very nice of you, dear, but you do quite enough to help round the place already. And you got your studies. You got to do well at school. That’s the way to get on in life.’

Scarlett sighed. She knew there was no shifting her mother on that point.

‘Well, get someone else in, then. Just someone to serve behind the bar on a couple of evenings, so you wouldn’t have to work every day. Everyone else has a day off a week, Mum. Why shouldn’t you?’

Unspoken between them was the fact that Victor went to football every Saturday afternoon and to the greyhound racing at Southend every Wednesday evening without fail.

‘Get someone in? A barmaid? Oh, I don’t know about that, lovey. We couldn’t afford the wages. Things are tight enough as it is, without starting paying other people to do what I can perfectly well do myself.’

‘But Mum—’

‘Look, I’m all right, see? There’s nothing wrong with me that another cup of tea won’t cure.’

She certainly didn’t look as white and clammy as she had done a few minutes ago. But Scarlett couldn’t shake the persistent anxiety gnawing at her overfull stomach. This wasn’t the first time her mother had had one of these turns.

‘But Mum—’

‘Enough said, pet, right? I don’t want to hear no more about it. We didn’t come into this world to have an easy ride. You got to keep at it, like Scarlett O’Hara. She never let anything stop her. Wars, famine, whatever, she still kept right on. That’s why I named you after her, Scarlett. I wanted you to be like her—fearless, not a little mouse like me.’

‘You’re not a little mouse, Mum.’

Scarlett had heard this story countless times before. It was one of her mother’s favourites.

‘Oh, but I was. Still am, really. Of course, I didn’t have much of a choice. I had to look after my mum and dad, didn’t I? First him and then her, both of them invalids. All those years.’

Joan sipped at a fresh cup of tea, looking inwards, back down the years. The commentator on the wireless was describing the crowds gathered for the coronation, but neither woman heard him.

‘Thirty-seven, I was, when poor Mum died. Never had a job, never went out dancing with young men, never done nothing except go to the library and borrow lots of books. Didn’t know how to do anything but run a house and look after invalids. And there I was, alone in the world with the rent to pay and no pension nor nothing coming in now they’d passed on, God bless them. So I thought I’d better get something doing the same thing. I couldn’t be a proper nurse—I didn’t have the training—but I thought maybe I could get something live-in with another invalid. And I guess I would have done just that, and been a poor old maid with no life of my own, if I hadn’t—’

‘—met my dad,’ Scarlett said for her.

Joan smiled. Her voice was soft with love. ‘Yes. Your dad. Oh, he was so handsome! Like a film star. Tall, dark, lovely black hair he had, just like yours, and those flashing dark eyes, and that lovely smile. Just waiting there at the bus stop he was. My fate. Just think, if I’d got there five minutes later, I’d of missed him, and then I wouldn’t be Mrs Smith now, and you would never of been born. Just think of that! No Scarlett in this world. No wonderful daughter to love and watch over. Best thing that ever happened to me, you are.’

‘Oh, Mum—’ Scarlett leaned over and gave her mother a hug. ‘You soppy old thing.’

‘I mean it,’ Joan insisted, hugging her back, stroking her hair. ‘I couldn’t ask for a better daughter than you. My Scarlett. Gone with the Wind. Oh, how I loved that book. Scarlett O’Hara was everything I wasn’t—she was rich and beautiful and brave and she didn’t care what she said or who she took on. And just look at you! You’re beautiful and brave, and maybe one day you’ll be rich.’

‘Oh, yes, and then I’ll have a big house with a swimming pool, like a film star,’ Scarlett said.

It was a game they often played, the When I Am Rich game. Sometimes it was Scarlett who was going to become rich, by marrying a millionaire or being a beauty queen, sometimes it was Joan, who was going to win the football pools.

‘Wasn’t so long since you wanted a pony and a pink taffeta dress.’ Joan sighed. ‘Now it’s a big house with a swimming pool.’

‘Yes, well, I’m fourteen now,’ Scarlett reminded her.

‘Fourteen. Quite the young lady.’

Joan held her daughter’s face between her hands and looked at her long and hard. Then she gave a nod and stood up.

‘Yes, quite grown up. Grown up enough to read Gonewith the Wind. I’ll fetch it for you.’

She bustled out of the door. Scarlett started to clear the table and pile the plates up by the sink. At last she was going to be allowed to read the story that had figured in her mother’s tales ever since she could remember. Since she had joined the adult section of the public library, her hand had often hovered over a copy of the novel. She had even picked it up, opened it, read the first page. There was nothing to stop her from borrowing and reading it, nothing except the amazing grip it held on her mother’s imagination. It had been held out to her as a huge treat, something to look forward to, something almost as good as marrying a film star or winning the football pools, except that the sensible part of her knew that she would probably never do either of those things, whereas one day she surely would get to read all about her namesake.

‘Here we are.’

Her mother came back into the kitchen and sat down at the table, breathless, holding her side.

‘Oh, dear me. Those stairs. I swear they get steeper every day. There—here it is. I’ve read it so many times it’s a wonder the pages haven’t worn out.’

Scarlett took the book and ran her hands reverentially over the cover. She looked at the spine. Gone with theWind by Margaret Mitchell. She opened it up and read the first line, the first paragraph, the first page. She was transported back ninety years or more to the front porch of a plantation house in Georgia. Such a strange world, so very different from her own.

Her mother touched her shoulder.

‘Things to be done, pet.’

‘Mu-um—’ Scarlett protested. ‘You can’t give it to me, then tell me I can’t read it!’

‘Well, maybe I shouldn’t of, but we got to get going, love.’

Joan had her hands in the sink. The first of many lots of washing up she would be doing today, what with all the glasses people would be using. Scarlett read one more paragraph, sighed dramatically and walked over to pick up the tea towel.

By the time Victor sauntered down the stairs the morning’s chores were all done and Joan and Scarlett were glued to the wireless.

‘What’s all this, then?’ he asked, squeezing Joan’s shoulder, kissing Scarlett’s cheek. ‘Slacking on the job?’

‘Oh, it’s so wonderful,’ Joan breathed. ‘All the singing and that. He describes it so well. The people and the robes, all the colours. I just wish we had one of those televisions. It must be wonderful to watch it all going on.’

‘It’s what we do best, ain’t it?’ Victor said. ‘Us British. We do pomp and ceremony best in the world.’

He pulled up a chair and lit a cigarette. Scarlett made her parents another cup of tea each and left them sitting contentedly, one either side of the big brown wireless, while she picked up the precious copy of Gone with theWind and went to her room to change. Like everyone in the country who could possibly afford it, she had a new dress to wear for Coronation Day. It was blue cotton with white polka dots, with a tight bodice and a fashionably full skirt. She tied a long red, white and blue striped ribbon round her ponytail and then turned this way and that in front of the small mirror over the chest of drawers, trying to get a full length view of herself. What she could see pleased her. She put her hands to her slim waist and pushed it in still further, smiling at her reflection. She might not be a southern belle like Scarlett O’Hara, but today was a special day and she was going to enjoy it.

CHAPTER TWO

‘TWO more pints o’ that there Coronation Ale, if you please, young missy!’

‘Coming up, sir!’

An anomaly in the licensing laws allowed Scarlett, as the licensee’s child, to serve alcohol even though she was too young to drink it. She pulled the beer carefully into the jugs, as she had been taught. It was no use rushing a good pint.

Beside her, her mother pushed a strand of hair back off her damp forehead.

‘Scarlett, love, when you’ve done that, can you run round and get the empties? We’re almost out of clean glasses.’

‘Righty-oh, Mum.’

The Red Lion was jumping. There was a roar of happy voices from both bars and a pall of blue smoke hanging over everyone’s heads. Nobody could remember seeing so many people in since VE day. Crowds of men and quite a number of women were packed into the two bars and children were running around on the village green outside clutching bottles of pop and shrieking. Everyone was in an excellent mood, and of course there was only one topic of conversation.

‘…she looked so beautiful, sort of stately, like…’

‘…and the two little kiddies, they behaved so well, didn’t they?’

‘That Queen of Tonga, she’s a character, ain’t she? Sitting in the rain there, waving away to the crowds!’

Scarlett squeezed her way between the cheerful customers. Those who had managed to get tables piled the empties up for her and handed them over.

‘There y’are girl, and here’s a few more. Can you manage? Oh, she’s a chip off the old block and no mistake. You going to be a landlady when you grow up, young Scarlett?’

‘Not on your nelly,’ Scarlett said to herself. She had other ideas for her future. An air hostess, maybe, or a lady detective, tracking down ruthless murderers, or more practically, a lady chauffeur, driving rich and famous people about in a swish car.

She wriggled past her father’s little group of regulars on her way out to the kitchen. Even he was on the business side of the bar this evening. He was only attending to his cronies, but at least he was doing that and he was keeping them well topped up. They were on whisky chasers, Scarlett noticed.

‘Ah, here’s the prettiest little barmaid in all of Essex,’ one of them exclaimed as she tried to force her way through. ‘Aren’t you afraid some young fella-me-lad will come and whisk her away, Vic?’

Her father smiled at her between the flushed faces.

‘Ah, she’s still Daddy’s girl, aren’t you, my pet?’ he said, lifting the flap in the bar to let her through.

‘That’s right,’ Scarlett agreed. Most of the boys she knew were gangling and spotty. Not like the heroes of books and films.

There were more dirty glasses lined up on the bar. She piled those onto a tray with the ones she had collected already, staggered through into the back room and kicked the door closed behind her.

‘Phew!’

It was cooler and the air was much clearer out here. Better still, there were no raucous voices calling out to her. It was tempting to linger over the washing up, spinning out the time before going back into the bar. Her school friends would all be at home or round at friends’ or relatives’ houses enjoying themselves this evening. They’d be playing card games or watching repeats of the day’s ceremony on their new televisions, not rushing about working. She thought of the copy of Gone withthe Wind waiting for her upstairs. How nice to be able to slip up there now and escape into Scarlett O’ Hara’s world and just listen to the rumble of voices coming up from below, like she used to when she was younger.

‘Hey, Scarlett, my pet!’

Her father’s head appeared round the door.

‘Those glasses ready yet?’

‘Nearly.’

Scarlett dried the last one and hurried out with the loaded tray. Her parents immediately grabbed them and started pouring fresh drinks.

‘Good girl—can you do the ashtrays now?’ her mother asked. ‘Yes, Mr Philips? Two best bitters and a mild, was it? And a G and T. Right. Mrs Philips here too, is she? How did the children enjoy the tea? All right, sir, be with you in a minute. Yes, I know you’ve been waiting. Scarlett, leave the ashtrays and serve this gentleman, will you?’

Scarlett concentrated on the impatient customer as he reeled off a long and complicated round. Over on the far side of the public bar, a sing-song had started.

‘Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do—’

Others took up the song until the whole bar had joined in.

‘I’m half crazy, all for the love of you—’

‘Two port and lemons, a rum and blackcurrant, half of bitter shandy, a Guinness—’ Scarlett muttered to herself, adding it up in her head as she went along.

People in the lounge bar heard the singing and started up a rival tune.

‘Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves—’

‘Oh, and a pint of Coronation Ale, love,’ Scarlett’s customer added, shouting above the noise.

Both songs were going full blast, but the lounge bar crowd didn’t know all the words to Rule Britannia, so they contented themselves with singing the chorus three times and tra-la-ing in between. The public bar finished Daisy, Daisy and started on Roll out the Barrel. The lounge bar lot gave up competing and joined in too. Scarlett finished her round and took the money. As she rang it up on the till, there was a crash and a thud behind her. She spun round and cried out loud. Her mother was slumped on the floor surrounded by broken glass and a pool of beer. Her face was deathly pale and her lips a dreadful bluish colour. Scarlett bent down beside her.

‘Mum, Mum! What’s the matter?’

‘Joannie!’

Victor crouched at the other side of her, patting her cheek, shaking her arm. His face was as flushed as hers was pale.

‘Joannie, what is it? Come on, Joannie, speak to me!’

Joan’s eyes were staring. Jagged groans tore from her mouth as she struggled to breathe.

‘What’s up? What’s wrong?’

People were leaning over the bar.

‘Joan’s had a funny turn.’

‘Get her into the fresh air.’

‘Get a doctor.’

One of the regulars lifted the flap and joined them behind the bar.

‘Come on, Vic, let’s get her out the back.’

In an agony of worry, Scarlett followed. She grabbed a cushion from one of the chairs to put under her mother’s head as the men lowered her mother gently to the floor, then Scarlett crouched beside her, holding her hand and feeling utterly helpless. What could she do? She wanted so desperately to help her mum and didn’t know how.

A woman came in. ‘Can I help? I’m a nurse.’

Scarlett felt a rush of relief. Here was someone who could advise them.

Victor welcomed her in. As she knelt by Joan, a man put his head round the door.

‘Someone’s gone for Dr Collins. How is she?’

‘Thanks,’ Victor said. ‘I don’t know. She’s—’

‘Ring for an ambulance,’ the nurse cut in. She looked at Scarlett. ‘You’ll be the quickest. Run over to the telephone. Do you know how to do it? Ring 999 and tell them it’s a heart attack.’

Fear clutched at Scarlett’s entrails. A heart attack! Her mum was having a heart attack! Wordlessly, she nodded and sprang to her feet. She was out of the back door, round the side of the pub and across the village green in seconds, running faster than she had ever run in her life. Her lungs heaving, she wrenched open the heavy door of the telephone box on the far side of the green from the Red Lion, picked up the receiver and dialled 999. She struggled to control her breathing so that she could speak clearly.

‘Ambulance—my mum—the nurse said she’s having a heart attack—’

A calm female voice on the other end of the line took the details and assured her that an ambulance would be with them as soon as possible. Scarlett replaced the phone and stepped out into the summer evening again. Everything was carrying on as if nothing had happened. Houses were bright with flags and bunting for the big celebration. Across the green, the door of the Red Lion stood open and children were still playing outside. Someone cycled past and called out a greeting to her. It all felt unreal, as if she were watching it on the cinema screen. This couldn’t really be happening, not to her. It was all too much, too fast. One moment she had been serving a customer, the next she’d been telephoning for an ambulance. A heart attack. It wasn’t right. Men had heart attacks, not ladies, not her mother.

‘Mum!’ she cried out loud. ‘Oh, Mum!’

She set off across the green again, ignoring the shouts of the children as they chased round her. Out of the corner of her eye she noticed two other figures hastening towards the pub. Something made her look again, and then she veered over to meet them.

‘Oh, Dr Collins, thank you, thank you—it’s my mum—’

‘I know, I know—’

The doctor was an elderly man, past retirement age. Already he was out of breath, and the man who had gone to fetch him was carrying his bag for him. Like the rest of the village, he must have been celebrating, for he was wearing evening dress and Scarlett could smell drink on his breath. He put a heavy hand on her shoulder as he hurried along.

‘Don’t worry, young Scarlett—’

Scarlett hovered by his side in an agony of impatience. She knew he was going as fast as he could, but he was so slow, so slow! She wanted to drag him along.

‘Come round the back,’ she said as they reached the Red Lion.

She knew as soon as she and the doctor went through the door. She knew by the way they were standing, by the way they turned as she entered the room. She knew by the look on their faces.

‘Mum?’ she croaked. ‘She’s not—? Please say she’s not—’

There was a ringing in her ears. Everything was blurred, everything but the woman lying on the floor, the dear woman who was the rock of her life, the one dependable point upon which everything else was fixed.

‘Mum!’ she wailed, running forward, dropping to her knees. She grasped one of the limp hands in hers, clasping it to her chest. ‘Mum, don’t go, don’t leave me!’

Hands were restraining her, arms were round her shoulders. She shook them off.

‘No, no! She can’t be dead, she can’t!’

Dr Collins was listening to Joan’s chest, feeling for a pulse in her neck.

‘Do something!’ Scarlett screamed. ‘You’ve got to do something!’

Two strong hands were holding the tops of her arms now.

‘Now, then, that’s enough,’ a firm female voice was saying.

Scarlett ignored her. She was staring wildly at her mother, at the doctor, willing him to perform some miracle of medical science. But he just gave a sad little shake of the head.

‘I’m sorry, Scarlett—’

‘No!’ Scarlett howled. Her chest was heaving with sobs, tears welled up and spilled over in a storm of weeping. Her father was there, kneeling beside her, pulling her into his arms. Together they rocked and wept, oblivious to the people around them.

‘She was the best woman in the world,’ Victor croaked. ‘A gem, a diamond—’

Scarlett could only bury her face in his broad chest and cry and cry. It was like the end of the world.

After that came a terrible time of official things to be done. However much Scarlett and Victor wanted to shut out the world and mourn the dear woman who had gone, there were people to see, forms to sign, things to arrange. The funeral was very well attended. The Red Lion was a centre of village life. Joan had been there behind the bar all through the terrible war years and the difficult days of austerity afterwards. Everyone missed her round smiling face and her sympathetic ear.

‘She was a wonderful woman,’ people said as they left the church.

‘One of the best.’

‘Salt of the earth.’

‘She’ll be much missed.’

Standing by her father’s side, Scarlett nodded and shook hands and muttered thanks.

‘You’re a good girl,’ people said to her. ‘A credit to your mother, a chip off the old block.’

And all the while she wanted to scream and shout and rage against what had happened. This couldn’t be true, it couldn’t be happening to her. Her mother couldn’t really have gone and left her like this.

But she had, and there was worse to come.

CHAPTER THREE

ONE Saturday about three weeks after the funeral, Scarlett walked into the lounge bar to find her father sitting on a stool at the bar counter staring morosely at a letter. He looked dreadful. There were bags under his eyes, a day’s growth of stubble on his chin and he hadn’t bothered to brush his hair.

‘We’ve got to get out,’ he said.

Scarlett stared at him. ‘What do you mean, get out?’

‘The brewery wants us gone. They’ve been holding the licence for us since your mum—’ He hesitated. Neither of them could bring themselves to say the word died. ‘But they won’t go on doing that for ever. They want a licensee on the premises to deal with any bother.’

Long ago when Scarlett had first learnt to read, she had asked why only her mother had her name above the pub door as licensee. She had been told that the brewery preferred to have a woman in charge and, since the brewery’s word was law as far as they were concerned, she had never really thought to question it.

‘But surely they wouldn’t mind having your name up there now,’ she said. ‘You’ve been here for years. Everyone likes you. They all say what a good landlord you are. The brewery must know that, surely? And I could help as much as possible. We can keep it going between us.’

‘It’s not as easy as that,’ her father said.

‘What do you mean?’

Victor sighed. He dropped his head in his hands and ran his hands through his hair, making it stick up on end. Fear wormed through Scarlett’s stomach. This was her dad. When things went wrong, her dad was always there with his cheery manner, making it all right again.

‘Oh, we don’t have to bother ourselves about a little old thing like that,’ he would say. ‘Worse things happen at sea.’ Or, ‘It’ll all come out in the wash.’ And generally he was right. Up till now, whatever life had thrown at them, they had coped. Surely he could solve whatever was worrying him this time?

‘I can’t hold a licence,’ he admitted.

Scarlett stared at him. ‘Why not?’ she demanded.

‘Because I can’t, all right?’

Fear fuelled the anger that had been simmering in her ever since her mother had died.

‘No, it isn’t all right! You say we’ve got to leave here, leave the Red Lion, because you can’t hold a licence? I want to know why.’

‘Look, it’s best you don’t know.’

The anger boiled over, all the irrational resentment at what had happened, even at her mother for going and leaving them when they needed her so much.

‘I want to know! I’ve got to leave my home because of whatever it is. I’ve got a right to know!’

Victor rubbed his face and looked up at the ceiling. ‘Because—’ his voice came out as a croak ‘—oh, God, Scarlett, this is so hard. Worse than telling your mother—’

‘Go on!’ Scarlett raged.

Victor still wouldn’t look at her. ‘Because I’ve got a record,’ he admitted.

His whole body seemed to sag in defeat.

Scarlett did not understand at first. She gazed at her big strong dad, who used to throw her up in the air and catch her, who could move the heavy beer casks around the cellar with ease, who could down a yard of ale quicker than anyone. All at once he seemed somehow smaller.

‘A record? What do you mean? What sort of—?’ And then the truth dawned on her. ‘You mean a police record?’

She couldn’t believe it, wouldn’t believe it. It just wasn’t true. Her dad wouldn’t hurt a fly. He was everyone’s friend. He could not possibly be a criminal.

Victor reached out to her. Instinctively, Scarlett went to the safety of his arms. She was folded into the comforting familiarity of his scratchy jumper, his pubby smell. She felt his voice vibrate through his chest as he struggled to answer her honestly.

‘That’s about the size of it, yes.’

Scarlett felt as if she had been kicked in the stomach. Her whole view of the world lurched, shifted and rearranged itself into a darker, more frightening picture.

‘What did you do?’ she whispered into his neck, as visions of robbery, of murder rose in her head. Desperately, she drove them down, hating herself for even entertaining such horrors.

‘Breaking and entering.’

A burglar. Her father was a burglar.

‘You went into someone’s house and—and stole things?’ she asked, appalled. ‘How could you? How could you do that?’

Wicked people did that. Her father wasn’t wicked. He was the kindest man in the world. She reared her head back, needing to see his expression. Victor looked stricken.

‘You think I don’t regret it?’ he countered. He held her by the shoulders now, his eyes boring into hers, willing her to understand. ‘There’s not a day doesn’t go by when I don’t wish I’d said no, but I was young and stupid, Scarlett. You got to remember that. It was wrong, I know it was wrong, but you got to think about what it was like then. Times were hard. It was back in the thirties, in the depression. Work was hard to come by and what jobs there was around wasn’t paid well. I’d just met this girl, a corker she was, and I wanted to impress her—’

‘My mum?’ Scarlett interrupted.

‘No, no, this was before I met your mum. But this girl, I wanted to take her out, show her a good time, and I hadn’t any money. Then this mate of mine, he said he was doing some decorating at this old girl’s place, and she had more money than sense and she wouldn’t even notice if we took a few bits. But she did, of course. And we got caught, and I got sent down—’

He paused. Scarlett’s heart seemed to be beating so hard it was almost suffocating her.

‘One stupid mistake and I ruined my life. My family cut me off. My mother died while I was inside and my brother said it was from shame over me and none of them have had anything to do with me since. And of course when I came out nobody wanted to give me a job. Who wants a man with a record when there’s plenty of others with a clean sheet? I was on my uppers by the time I met your mum. She turned everything round. She believed in me. She was a wonderful woman, your mum. The very best.’

Scarlett couldn’t take any more. She twisted out of his grasp, marched out of the building and went for a long walk, turning everything she had just learnt over in her head. None of it made any sense. She finally found herself back home again with everything still surging around inside. It was midday opening and there were a few customers in the bar. Not wanting to speak to anyone, she ran upstairs, grabbed Gone with the Wind from her bedside table and hurried down to the far end of the garden. Neither of her parents had been keen gardeners, so the patch had gone wild since the days of digging for victory. Down at the far end, beyond the apple trees, was a hidden sunspot. Scarlett lay down in the long grass with the sun on her back, opened the book and escaped into her namesake’s world. A little later she heard her father calling her name. She kept silent. Then she heard him scrunching down the gravel path at the side. It sounded as if he was going out. Scarlett read on, immersing herself in the burning of Atlanta.

Hunger finally drove her back inside. She walked down the garden with that faintly drugged feeling that came from living vividly inside another person’s life. The back door was open, of course. Her father had locked the front of the pub but nobody ever even thought of locking their back doors. As she went into the kitchen she glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. Six o’clock! Opening time, and her father wasn’t back. She put the kettle on, made a cheese sandwich and wandered into the serving area behind the bar, munching. Should she open up? She checked the till—yes, there was enough change. She ran an eye over the stock—yes, there was more than enough for the poor trade they were doing at the moment. But open up on her own—? In the kitchen, the kettle was boiling. Just as she was pouring the water into the teapot, her father walked in at the back door.

‘Scarlett! There’s my lovely girl, and the tea made too. What a little treasure she is.’

Scarlett regarded him. He was looking more cheerful than he had done ever since Joan had died. Almost elated. Despite everything she had learnt that day, hope surged inside her. Perhaps everything was going to be all right after all.

‘Where’ve you been?’ she demanded.

‘Southend.’ He spread his hands in an expansive gesture. ‘No need to worry any more, my pet. I’ve solved all our problems.’

‘You have?’

‘I have. I’ve got a job at one of those big places along the Golden Mile. The Trafalgar. And, what’s more, there’s accommodation to go with it. We’ve got a home and money. We’re going to be all right.’

Scarlett didn’t know what she felt—relief, anger, disappointment—it was all of these. On the face of it, her father had done just as he claimed. He had solved all their problems.

‘But we’ve still got to leave here,’ she said at last. ‘We’ve got to leave the Red Lion.’

Victor’s whole body seemed to deflate. ‘Yes,’ he admitted. ‘Well, there’s nothing I can do about that.’

Someone was thumping on the front door.

‘Anyone at home? There’s thirsty people out here.’

Victor ignored it. ‘Look, I don’t like it any more than you do, leaving all this—’ He waved his hand to take in the kitchen, the bars, the rooms upstairs. ‘I love it too, darling. Best years of my life have been spent here. But at least we got somewhere to go. That’s got to be good, now, hasn’t it, pet?’

Scarlett just shook her head. Up till now, some irrational part of her had held on to the hope that something might come up, that they might be allowed to stay. Now she knew it was really true. They were leaving.

‘If you say so,’ she said. ‘Don’t you think you’d better open up?’

Defeated, Victor went to unlock the door, leaving Scarlett to brood on their change of fortunes and all that it meant. It was only later that a faint feeling of guilt crept into her resentment. Her mother would not have reacted like that. Her mother would have congratulated him on his success in finding work and a roof over their heads. Sighing heavily, she made a cheese and pickle sandwich and a cup of tea and took it into the bar as a peace offering. Victor gave her a hug and turned to the little gang of regulars leaning on the bar.

‘Ain’t she just the best daughter in the world? A man couldn’t ask for more.’

Scarlett hugged him back and then turned to pick up the empties. As long as they still had each other, they would be all right.

The next couple of weeks passed all too quickly. Before they knew where they were, Scarlett and Victor found themselves in the delivery van belonging to Jim, one of the regulars, being driven into Southend-on-Sea with all their worldly goods packed into boxes and suitcases in the back. There wasn’t a lot. Hardest of all had been deciding what to do with Joan’s personal possessions. Neither of them could bear to give away her clothes and of course they wanted to keep her books and ornaments, but it was things like her comb with strands of her hair still in it that had broken their hearts. In the end, they had put everything into boxes and brought it with them.

They drove along the main road towards the town, then turned down a grand avenue with big houses on either side that led eventually to the High Street. In spite of herself, Scarlett began to take an interest. There were lots of shops with shiny big windows and displays of tempting goods. There were throngs of people, many of them obviously visitors in their seaside clothes. And there, at the end of the street was the sea, or rather the Thames estuary, grey-green and glittering in the summer sunshine.

‘Oh!’ Scarlett said out loud.

Their chauffeur grinned. ‘Pretty, ain’t it? Nothing like the sea, I always say. You seen the pier before?’

‘Of course,’ Scarlett said.

She’d been to Southend before, lots of times, and you didn’t go to Southend without seeing the pier. But still Jim insisted on acting as her tour guide.

‘Royal Hotel on your right here, Royal Stores pub on your left, and there it is, the longest pier in the world. Longer even than anything in America.’

‘Lovely,’ Scarlett said, as something seemed to be expected of her. And indeed she couldn’t help a traitorous lift of interest. The pier was an exciting sight, stretching out before her into the sea with its flags flying and its cream and green trams clanking busily up and down and its promise of fun and food and entertainment at the far end.

‘Do you think you’re going to like it here?’ Victor asked hopefully.

‘I don’t know,’ Scarlett said.

It was all very different from their village. It might be exciting, but it was alien. It wasn’t home.

She did not have long to admire the pier. The van plunged down Pier Hill to the sea front, and here they were surrounded by noise and colours and smells. There were ice cream parlours and pubs and amusement arcades and shops selling buckets and spades. There were families and big groups of men all dressed up for a day at the sea. Through the open windows of the van came music and laughter and shouting, dogs barking and children crying, together with wafts of candyfloss, fried onions, cockles and whelks. There was no hint of austerity here. Everything shouted, It’s a new beginning;let your hair down, enjoy yourself!

They drove along the Golden Mile. Victor was looking eagerly out of the window.

‘There it is,’ he said. ‘The Trafalgar.’

Scarlett followed his pointing finger. Their new home was a big yellow brick Victorian building between two amusement arcades. Two sets of double doors, closed at the moment, let on to the pavement and over the larger of them swung the sign, a painting of Lord Nelson’s famous ship, the Victory.

‘Best go round the back, I suppose,’ Victor said.

They drove on past the pub to the corner where the Kursaal stood, with its dome and its dance hall and its famous funfair. Round they went and up a small road that ran behind the sea front buildings. It was quieter here. There were back fences and bins and washing and a general morning-after feel. They stopped by a stack of crates full of empty beer bottles.

‘I’ll go and see what’s happening,’ Victor said, and disappeared into the back yard.

He came back with a young woman with a thin, over-made-up face and hair an unlikely shade of auburn.

‘This is Irma,’ he said.

Irma looked at Scarlett. ‘So you’re the kid, are you? You’re lucky. Missus don’t normally like kids living in, but we’re short of a cellar man and it’s high season, I suppose. Bring your stuff and don’t make a noise on the stairs. Missus and the Guv’nor don’t like being disturbed when they’re having their afternoon nap.’

Scarlett decided then and there that she didn’t like Irma and she wasn’t going to like her father’s employers. Glaring at Irma’s back, she picked up her bag of most treasured possessions and, together with Victor, followed her through the yard. It was a concrete area, dark and damp and smelly, totally different from the back garden at the Red Lion. The building towered over them, tall and forbidding. There was broken furniture in a heap on one side and a pile of kegs waiting to be returned on the other. A skinny cat slunk away at their approach.

‘The Missus says you’re to have the top back,’ Irma said, leading the way through the back door and along a dark passage that smelt of damp and stale beer and cats.

After a couple of turns and sets of steps and longer staircases, Scarlett was bewildered. How big was this place? How was she ever going to find her way around it? Irma stopped outside a door that looked just like the three others on the landing. She handed Victor a pair of keys tied together with a length of hairy string.

‘There y’are then. This is yours and that’s hers,’ nodding at the next door along. ‘Guv’nor wants you down at five to show you the ropes, all right?’

‘Right, yes, fine. Thanks very much, Irma,’ Victor said.

Irma clattered off down the lino-covered landing.

‘Well, then,’ Victor said. ‘Let’s see what’s what, shall we?’

He unlocked the door and stepped into the room. The faded cotton curtains were drawn and in the dim light they saw a single bed, a dark wardrobe, two dining chairs by a small rickety table and a chest of drawers with a cracked mirror above it. None of the furniture matched and the walls and lino and dirty rug were all in depressing shades of green, brown and beige.

‘Well—’ Victor said. ‘It’s got everything we need, I suppose.’

‘It’s horrible,’ Scarlett said.

She stepped over to the window and drew back the sagging curtains. They felt greasy. The view from the dirty window was of the back street they had come in from. She could see Jim there, still waiting by his van. She longed to rush back down and beg him to take her back to the Red Lion.

‘Want to see your room, pet?’

Scarlett sighed. ‘S’pose so.’

He unlocked the other door. This room was much smaller, hardly more than a boxroom, with just enough space for a single bed, a small wardrobe and a chest of drawers all set in a line along one wall. There was no rug, no wallpaper and the curtains didn’t quite meet in the middle. Scarlett hated it.

‘Better get our stuff in. Mustn’t keep Jim waiting any longer out there.’

Scarlett’s whole body felt heavy and listless. How was she going to bear living in this horrible place? Reluctantly, she followed her father down the maze of stairs and corridors to the back door. They unloaded the boxes into the back yard, thanked Jim, and lugged everything upstairs. By the time they had got it all in, Scarlett did at least know the way.

As they unpacked, she began to feel just a bit better. The wireless was placed on the chest of drawers with her parents’ wedding photo and one of herself as a baby. Their crockery and cutlery and cooking things were piled on the table. Scarlett made the single bed up rather awkwardly with the sheets and blankets and eiderdown from her parents’ double one. Then she turned her attention to her own little room. Her small store of books, her old teddy, her musical box and the pink glass vase she had won at a fair were set out, her hair things and clothes were put away. A photo of her mother on a beach, laughing, went on a nail conveniently situated on the wall above the bed, while her pink and blue flowery eiderdown went on it. It should have made the room seem more like home, but somehow seeing the familiar things in this alien setting only seemed to emphasise just how different it all was.

Her father tapped on the door and put his head round. ‘All right, pet? Oh, it looks better already, doesn’t it? You’re a born homemaker, just like your mum.’

Scarlett said nothing. She was trying hard not to burst into tears or scream with rage, she wasn’t sure which.

‘We’ll get one of those electric kettle things in the morning, so we can brew up,’ Victor went on.

It was only then that Scarlett fully realised that something was missing from their new living arrangements. ‘Where’s the kitchen?’ she asked.

Victor looked uncomfortable. ‘Well—er—there isn’t one. Not as such. But, like I said, we can get a kettle. And maybe one of those toasters. You know.’

‘But we can’t live on tea and toast!’ Scarlett burst out. ‘How can we live in a place where you can’t cook?’

‘Well—no—I’m sure there’s some way round it—’

‘And the bathroom—where’s the bathroom?’

Victor was on firmer ground here. ‘Oh, I found that. It’s down the first flight of stairs, second door on the left.’

‘So it’s not ours? We have to share it?’

‘Er—well—yes—’

It was all getting worse and worse. Scarlett felt as if she were trapped in a bad dream from which there was no waking.

Victor shifted uneasily. ‘Look—er—it’s nearly five. I got to go. Mustn’t be late for my first shift. Will you be all right here by yourself, pet?’

‘Oh, fine, just fine,’ Scarlett said with heavy sarcasm.

Her father reached out and patted her shoulder. ‘There’s my good girl.’

When he was gone, Scarlett went and sat on her bed. The place smelt all wrong. There were mysterious bangings of doors and muffled shouts coming from below. The tiny room seemed to close round her like a prison cell. It was all strange—strange and horrible. She reached for Gone with the Wind, but even that couldn’t distract her from the aching loneliness. She clapped the book shut, threw it on the bed and went out, clattering down the gloomy staircases towards the brightness and life outside.

In the downstairs passage she stopped short. Coming in at the back door was a tall fair-haired boy. He was wearing salt-stained khaki shorts, a faded red shirt open at the neck and a pair of old plimsolls. His skin was tanned golden-brown by the sun and he had a rolled-up towel under his arm.

‘Hello,’ he said. ‘You must be the new cellar man’s daughter.’ He held out his hand. ‘I’m Jonathan. I live here.’

Scarlett took his hand. It was warm and strong. ‘I’m Scarlett. How do you do?’

His smile broadened into one of delight. ‘Scarlett? Really? Like Scarlett O’Hara?’

Scarlett found herself smiling back. ‘That’s right. My mother named me after her.’

‘Well, I do declare!’ Jonathan said in a drawling southern states accent. ‘Welcome to the Trafalgar, Miz Scarlett.’

Suddenly, life didn’t seem quite so dreadful.

CHAPTER FOUR

JONATHAN’S first thought was that he made a very poor Rhett Butler. His first instinct was to keep her talking.

‘Where are you off to?’ he asked, without thinking. It sounded lame the moment it came out of his mouth.

‘Oh—just out,’ Scarlett said.

Scarlett—such a wonderful name. And it suited her. There was something wild and vivid about her. When his parents had said something about the new cellar man bringing his daughter with him, he’d not really thought about it. If he had any notion of what she might be like, it was a pasty-faced kid, someone who got in the way. Not a girl like this, with a challenging stare and a mobile mouth and the beginning of a woman’s figure showing through her thin cotton dress.

‘I’ll come with you, if you like. Show you round a bit,’ he offered.

‘I have been to Southend before, you know,’ Scarlett said.

Jonathan felt horribly rejected. He hid it with a nonchalant shrug. ‘OK. If you’d rather be on your own—’

To his delight, she looked slightly flustered.

‘No…I mean…I just thought you might have something else you wanted to do,’ she said.

‘Tell you what I do want to do, and that’s eat,’ Jonathan admitted. ‘I’ve been out all day in the Ray, and I’m starving.’

‘The Ray?’

Of course, stupid of him, she wasn’t local, she wouldn’t know what he was talking about.

‘It’s a channel of water out in the estuary beyond the mud-flats,’ he explained. ‘You sail out on the falling tide, then you can spend all day out there sailing and swimming and having races and that, and playing cricket on the Ray Sands. It’s brilliant. Do you sail?’

Scarlett shook her head. Her ponytail of dark, almost black hair shivered in glossy waves.

‘We lived in the country.’

‘Can you swim?’

‘Oh, yes. I learnt at school. I got my hundred yards certificate.’

‘Then you’ll have to come out with us one day. If you want to, that is.’

He found he was holding his breath. How wonderful if she said yes.

‘Thanks—yes.’

He felt like punching the air. Fancy taking her out for a whole day on the water! His mind raced, turning over how to bribe his friend to let him have the boat to himself, what time they would have to start, all the things he wanted to show her. But for now he had to keep her attention.

‘Are you hungry?’

She appeared to consider.

‘Yes. Yes, I am.’

She sounded almost surprised. He ran over the logistics in his head. It was just about the worst time to start cooking now. He came up with an interim plan.

‘Let’s go and get some chips, then. Irma or Marlene might want the kitchen at the moment, but we can go in when the pub opens and everyone’s busy.’

‘Marlene?’ Scarlett said.

‘Yes, she’s the other live-in barmaid. Haven’t you met her yet?’

‘No. Won’t your mum be expecting you?’ she asked.

Jonathan had to stop himself from giving a derisive laugh. His mother, expecting him? That would be the day.

‘Oh, she doesn’t know I’m in yet,’ he said, which was true. ‘You never know quite when you’re going to be back when you’ve been out in the boat. So do you fancy some chips?’

Scarlett nodded.

‘Yes, please. I’ll just go and get some money.’

Suddenly it seemed very important that she didn’t leave.

‘Don’t worry, I’ve got some,’ Jonathan assured her, jingling some change in his pocket.

‘But I—’

‘Look, I’ll get them this time and you can next, all right?’

She hesitated a moment, then agreed. He couldn’t believe how smoothly it was going. In the past when he’d tried to talk to girls, they’d either go all giggly and silly or look at him as if he were some lower form of life. But Scarlett talked to him like…well, not quite like a friend, because there was more to it than that. He didn’t know what, couldn’t put a name to it, but it was there all the same.

Walking with her along the sea front, Jonathan felt ten feet tall. They could all see him with this pretty girl, all the people he knew. He glowed as the funfair attendants called out to him, the girl behind the ice cream stand waved, the elderly Italian lady winding pink candyfloss round a stick blew him a kiss. When they got to the chip shop, he was greeted like a long lost son by the big motherly woman behind the till whom he always called Aunty Marge, although she wasn’t any sort of relation.

‘Ah, here’s our Jonno! Talk about return of the wanderer. You been avoiding us or something? Look at you, you’re fading away. You need a good feed-up, you do. Douggie!’ she called to the equally large man sweating over one of the fryers. ‘Nice big bag of chips for our Jonno. And stick a pickled egg in while you’re about it.’

Jonathan grinned. ‘Thanks, Aunty Marge. And my friend Scarlett here’d like some chips as well.’

Scarlett stood up well to being scrutinised.

‘Scarlett, eh? And where’ve you sprung from?’

‘My dad’s just started work at the Trafalgar.’

‘Oh, so you’re going to be living down here, are you? Going to be one of us. What do you think of it so far?’

Scarlett shrugged. ‘It’s all right,’ she said.

Jonathan winced inwardly. Aunty Marge was not going to take kindly to such a lukewarm reaction.

‘All right? All right? You’ve come to live in London’s playground and that’s all you can say for it? Shame on you! You’ve not been trying hard enough, Jonno. Go and show her all the sights. Give her a ride on the speedway.’

‘I’m going to, Aunty Marge,’ he assured her.

‘Right.’ Aunty Marge gave Scarlett one more up-and-down look. ‘Pretty girl. Needs more flesh on her bones, though. Better stick an egg in hers as well, Douggie.’

To the annoyance of the queue of hungry customers, Jonathan and Scarlett’s bags were handed over ahead of everyone else’s. They shook on lots of salt and vinegar, Jonathan paid and they both promised to come back soon.

Outside seemed pleasantly cool after the steaming heat and overwhelming smell of boiling fat in the chip shop. He watched as Scarlett tried a chip. It was so fresh out of the fryer that she could hardly hold it. Crisp on the outside and soft and fluffy on the inside, Aunty Marge’s chips practically melted in the mouth.

‘Cor, lovely!’ Scarlett mumbled, breathing air in to stop her mouth from burning.

‘Best chips on the Golden Mile,’ Jonathan claimed. ‘Come on.’

He led the way across the wide road, past seafood stalls and ice cream kiosks to lean on the rails overlooking the beach. He loved this view, loved it in the winter when it was empty and windswept, and in a different way now in the summer, when it was crowded with day-trippers. Families were packed together on the pebbly sand, the mothers and fathers sitting in deckchairs with their knitting and their newspapers, the children digging sandcastles, paddling and filling pails of water. At the water’s edge, a big open sailing boat was waiting for passengers to come aboard for a ride out on the sea. Beyond that, cockle boats bobbed at their moorings and, as a backdrop to it all, marching out into the sea was the pier.

‘So where do you come from?’ Jonathan asked in between chips.

‘A village the other side of Rochford.’

‘And what brought you here?’

‘My dad needed a job.’

‘It’s just the two of you, is it?’

‘Yes.’

It was obvious that she was uncomfortable, that she didn’t want to talk about it. He recalled what his mother had said about the new cellar man. ‘Bit of a loser, if you ask me. But what can you do? It’s high season and we need someone.’ He tried a different tack.

‘It was nice, your village?’

‘Oh, yes—’ Scarlett started to tell him about it, a faraway look on her face. It all sounded pretty ordinary to him. She went on to describe the pub where she had lived, the Red Lion.

‘It was such a nice little place.’ She sighed, licking her finger and dabbing up the last pieces of crispy potato round the bottom of the bag. ‘It had lovely old beams, and lots of horse brasses, and benches against the wall outside. My mum and me kept it all spick and span. And in the summer I always kept a nice jug of wild flowers on the bar. Just to make it look homely, like. And at Christmas we really went to town, holly and ivy and paper chains and everything. It looked really lovely. And people used to cycle out from Rochford, and even from Southend just to have a pint with us. My dad kept the best pint for miles around. Everybody said so.’

‘Sounds wonderful,’ Jonathan said politely. ‘A proper village pub. Very different from the Trafalgar.’

He gazed out to sea, to where huge cargo ships were making their way up the Thames to the London Docks, deliberately avoiding looking at Scarlett as he asked the obvious question.

‘So why did you move here?’

‘Oh…well…you know…like you said, it’s different. A new start.’

She tried to make out it was a good thing, but it didn’t quite sound convincing.

‘Right,’ Jonathan said. He knew just what was going on. He gave her a sympathetic smile. ‘Parents, eh? What can you do with them? They say it’s all for the best and they’ve got your best interests at heart and all that sort of rot, but when it comes down to it, they never listen to you.’

Scarlett hesitated, then said, ‘Too true.’

In front of them, the beach was beginning to clear. Mums were packing up picnic baskets and cleaning sand off tired children’s feet, dads were folding away the deckchairs and searching for lost buckets and balls. Jonathan glanced at his wrist, realised he wasn’t wearing a watch and stretched across to take Scarlett’s arm, turned it slightly and looked at the time. The living warmth of her arm beneath his hand sent a hot thrill through him.

‘Thanks,’ he said, as casually as he could. ‘I left mine at home. No good wearing one on the boat, it might get ruined in the water. It’s gone half past six; shall we go back and get something proper to eat? The chips made a nice amuse bouche but I’m dying for a proper meal.’

He could have kicked himself. It sounded so pretentious.

‘Amuse bouche?’ Scarlett questioned, her forehead creasing in thought. ‘Mouth amusement?’

Jonathan laughed with relief. She hadn’t thought he was trying to get one over on her.

‘Well done. That’s more than most people know. It’s a French restaurant term. It means a little twiddly tasty bit before the real starter, or in between courses. Something to keep the appetite interested before the next main event.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Scarlett said airily.

Jonathan screwed up his chip paper and lobbed it into the nearest litter bin.

‘Come on, the kitchen’ll be all ours now.’

As they made their way back through the raucous crowds and close-packed heat of the Golden Mile, he tried to decide just where to take her. What was she going to think if they stayed in the staff kitchen? It was going to look really unfriendly, as if he thought she wasn’t good enough to be invited upstairs. But his mother was so adamant about not letting staff into their private quarters. Not that Scarlett was staff, of course, but that was stretching the point a bit. He tried to assess the odds against his mother coming in and finding them there. It was high season, and it was Friday evening, the second busiest night of the week. She should be run off her feet in the bar all night. But if she was to pop up for something…no, it just wasn’t worth the risk.

By the time they arrived at the dark rear of the Trafalgar, Jonathan had made his mind up. He led the way to the staff kitchen, which looked out over the yard.

‘I’ll just run upstairs and get some stuff,’ he said. ‘You won’t have had time to do any shopping, will you, what with moving and all that?’

‘No, well, there wouldn’t be much point, would there? We’ve got nowhere to cook,’ Scarlett said.

Jonathan was mystified. ‘But this is the staff kitchen. Didn’t you know that? You and Irma and Marlene share this.’

‘Oh…’

He could practically see light dawning on her expressive face.

‘My dad must’ve forgotten to tell me,’ she said.

‘Yeah, right,’ he agreed. ‘Look, make yourself at home. I won’t be a mo. Perhaps you could put the kettle on for me?’

‘OK.’

Mercifully, she didn’t seem put out to be left there. He raced upstairs, unlocked the heavy door marked ‘Private’and went into the kitchen. If only he had known he would be cooking for a girl! As it was, he would have to improvise with what was around. He opened the cream-coloured door of the American refrigerator and took out bacon, eggs and cream, then rummaged in the cupboards for pasta, onions, garlic, olive oil and ground coffee. He piled the whole lot into a basket together with the chopping board, his French chef’s knife and the percolator. A glorious mix of excitement and nerves churned inside him. Supposing she didn’t like his cooking? Supposing she laughed at him? But she couldn’t—she mustn’t—because that would mean the end of their friendship before it had hardly started.

He galloped downstairs again to find the kettle starting to whistle while Scarlett leaned against the chipped enamel sink staring out at the back yard. There was a horribly bleak expression on her face that cut right through him.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked, dumping the basket on the table.

Had his mother been in and had a go at her? His heart sank at the thought.

‘Oh…nothing…’ She straightened up, forcing a smile.

‘Only you looked…well…’

‘I’m all right. Really. What on earth have you got there?’ She moved over to look at the contents of his basket.

‘Just a few things to make a meal. Would you like to be my commis chef?’ he asked. ‘I’ll have that boiling water in a big saucepan with salt in, please, and butter and some olive oil in a frying pan.’

‘Olive oil?’ Scarlett questioned. ‘Olive oil’s for putting into your ear when you’ve got earache.’

Jonathan stopped himself from laughing. It wasn’t her fault. She didn’t know, any more than most people in this country did.

‘Mine isn’t,’ he said, handing her the bottle. ‘Mine’s for cooking, and making salad dressings.’

Scarlett made a face and looked at the French writing on it. Cautiously, she poured a small pool of oil into a pan. Jonathan got on with skinning and chopping a couple of onions. Scarlett stared at him as he sliced them expertly with a rocking motion, just as he had been taught.

‘How did you learn to do that? Did your mum show you?’

Jonathan laughed.

‘Mum? No, Mum hates cooking. I’ve got French relatives. I go to stay with them most summers.’

Wonderful summers with lovely Tante Jeanne-Marie, who tucked him under her wing with all her other chicks and made him feel loved and wanted. Racing around on bikes and swimming in the river with the cousins…

‘And they make you do the cooking for them?’ Scarlett was saying.

He wrenched himself back from sunny days in Mont Saint Etienne.

‘Far from it! I’m allowed to help. My aunt’s a wizard cook. Her brother’s a chef and owns a restaurant. They’re all really keen on food. It’s not like here at all. They all sit round the table and discuss what they’d like to eat for the coming week, then they go to the market together and buy the fresh stuff, and they argue while they’re going round even if they’ve agreed beforehand what they want, like, if they’ve bought some lamb, should they cook it this way or that, and what other things they need to get to go with it, and whether they’ve got the right stuff in the larder at home. It’s really interesting. It makes you think about tastes and flavours and textures and how things go together and complement each other.’

Scarlett was gazing at him in amazement. Jonathan felt hot, and then defensive. Food was important. If she didn’t realise it now, then he would prove it to her. He crushed a clove of garlic with the blade of his knife, chopped it into minute pieces and put it in the pan with the onions where they sizzled merrily, giving off a glorious smell.

‘What was that?’ Scarlett asked.

‘Garlic.’

Garlic was what foreigners were supposed to stink of. Well, at least foreigners knew how to eat.

‘Are you doing something French now?’ Scarlett wanted to know.

‘No, this is Italian, because I’m starving and there’s nothing like a big plate of pasta for filling you up,’ he explained. ‘Pass us the spaghetti, would you?’

‘Spaghetti?’

Scarlett looked at the ingredients on the table. She was searching for the stuff that came in a tin, he guessed.

‘In the blue packet,’ he prompted.

She found the right thing and watched as he opened it up.

‘It’s like long thin macaroni,’ Scarlett said.

‘Same family. It’s all pasta.’

Jonathan stood it in the pan, gradually pushing it under the boiling water with a wooden spoon as it softened.

‘Have you got an Italian aunty as well?’

‘No—I learnt this off Mrs Mancini along the road. She’s only got girls, so she sort of adopted me. I was a really skinny kid, and she used to sit me in her kitchen and feed me up until I couldn’t move.’

There was a time when he’d spent more time with the Mancinis than he had at home. He was always made to feel welcome there.

Jonathan chopped, stirred and tasted. He added bacon lardons, beaten eggs and cream. Finally he drained the spaghetti, mixed it with the sauce, divided it between two plates and put one down in front of Scarlett with a flourish.

‘Spaghetti alla carbonara!’

‘Wow—’ Scarlett looked suitably impressed. ‘It smells delicious.’

She picked up her spoon and fork and tried to capture the slippery pasta. Jonathan remembered the first time he had eaten spaghetti, when he was about eight, how Mrs Mancini had stood behind him and guided his hands, her comforting warm body pressing into his back.

‘It’s a so-and-so to eat, isn’t it?’ he said. ‘There’s a knack to it—look—’

He demonstrated. Scarlett copied, with much laughter.

‘I did it! I did it!’ she cried, as she managed to get the perfect amount of spaghetti twiddled round her fork. She carried it to her mouth, and her eyes closed with pleasure. ‘Mmm—gorgeous—’

Jonathan relaxed. She liked it. Everything was well with the world. They ate and they talked, they found they liked the same music, the same films. Jonathan made some proper coffee in the percolator, another new taste for Scarlett, and they began a long argument over whether Rock Hudson was a better actor than Clark Gable. He was just acting out a scene to prove his point when the door opened.

‘Jonathan, I thought I could hear your voice. What on earth are you doing in here?’

It was his mother. Jonathan broke off in mid-sentence.

‘I was just…’ he began.

But she wasn’t listening. His mother was staring at Scarlett as if she were an armed robber.

‘And just who might you be?’ she demanded.

CHAPTER FIVE

THE newcomer was a hard-faced woman of forty or so with grey eyes as cold as pebbles and a helmet of wiry brown hair. She was staring at Scarlett with undisguised hostility. This must be the Missus, whom Irma had said mustn’t be disturbed and didn’t normally allow children. Scarlett disliked her on sight.

‘I’m Scarlett Smith, Victor Smith’s daughter,’ she said, holding that cold gaze unflinchingly.

‘Really?’ The eyes swept over her again. ‘I thought you were younger than… How old are you?’

‘Fourteen.’

As soon as the word was out of her mouth, Scarlett wondered if she should have lied. Supposing her father lost his job because this dreadful woman didn’t like girls her age? Two or three hours ago, before she’d met Jonathan, she would have been glad to get out of this place, but now it was different. She had a reason to stay.

The Missus’s mouth closed into a straight line of disapproval.

‘Hmm. You look older. Well, you’re more than old enough to know where you should and shouldn’t be round here. No going in the bar area during opening time, or at any other time unless you’re specifically told to by me or the Guv’nor, and no going into our flat upstairs, even if Jonathan here invites you. Is that clear?’

‘Very.’

Scarlett’s original dislike was turning into loathing by the second. She couldn’t remember ever having met such an unpleasant woman. She glanced at Jonathan. He was looking acutely embarrassed. She immediately felt overwhelmingly sorry for him. How dreadful to have a mother like that.

‘Good.’

The Missus held her eyes for a few moments more, as if she knew of the resentment boiling within her and was enjoying it. Then she turned to look at her son.

‘You’d better get upstairs straight away.’

‘We haven’t washed up yet,’ Jonathan said.

‘Never mind that. She can do it. I take it that’s our food you’ve been giving her?’

‘I was making her feel at home,’ Jonathan stated.

‘So I can see. Now you’ve done it, you can go upstairs.’

‘Not until I’ve cleared away.’

Jonathan stood up and started piling the plates and cutlery. Taking his cue, Scarlett picked up the cups and saucers. She was about to take them over to the sink when a hand descended on her shoulder and held her in a grip of iron. It was all Scarlett could do not to cry out.

‘You—’ the Missus’s voice was low and menacing in her ear ‘—put those down.’

‘You’re hurting me!’

‘Mum!’ Jonathan yelled.

‘Put. Them. Down.’

Scarlett did so.

‘You’re not at your own place now, young woman. You’re at my place. You can’t do what you like—you do what you’re told. Understood? You and your father can be out on your ear at any time. Now, go up to your room.’

She was released with a push towards the door. Shocked, Scarlett stumbled round the scarred table. Nobody, not even the scariest of teachers, had ever spoken to her like that in her life. In the doorway she paused and looked back at Jonathan. He was flushed with anger. Scarlett’s courage flared. Ignoring his mother, she spoke to Jonathan.

‘Thanks ever so much for that supper. It was the best meal I ever tasted.’

His tense face relaxed into a smile.

‘My pleasure. I’ll see you tomorrow, OK?’

‘OK.’

And she made off before his mother could ruin it.

By the time she had run upstairs to her room, she was shaking with fear, anger and a sort of wild triumph. She and Jonathan had not let that witch have the last word. She slammed the door shut behind her and flung herself on the lumpy bed, her heart thumping.

‘You cow,’ she said out loud. ‘You cow.’

And it swept over her how far away from home she was. The life she had known—the Red Lion, her friends in the village—all of that was gone for ever. Much more than that, her mother had gone. While they had stayed on at the Red Lion, it was as if she had just gone away on a visit for a while. Her spirit was in every nook and cranny of the place. Even though Scarlett had seen her dead on the kitchen floor, had been to the funeral and seen her lowered into the earth of the churchyard, still she had felt her mother there, just beyond touching. But this place was different. It was cold and hard. Her mother would never reach her here. Scarlett lay on her face and wept.

She must have gone to sleep at last, because the next thing she knew was her father bending over her. He kissed her cheek, shut the door gently and went out. Scarlett slid once more into a sleep of emotional and physical exhaustion.

When she woke again it was morning. She realised she was fully clothed and lying on top of the covers. Outside, seagulls were crying. It was the first full day of her new life. The Trafalgar was still horrible, the Missus was still a dragon, her old life was still gone for ever, but in daylight it somehow didn’t seem quite as bad as it had last night. She lay there for a moment thinking about Jonathan. What a nice person he was, and full of surprises. Had he meant it when he had asked her to go sailing with him? Sometimes when people said things like that, they didn’t really expect you to take them up on it, but somehow she thought that when Jonathan said something, he meant it. She desperately hoped so. With Jonathan here, her new life was bearable.

She slid out of bed to get her washing things and go to the bathroom, and noticed a folded piece of paper on the floor. It looked as if it had been pushed under the door. She picked it up, and found to her delight that it was a note from Jonathan.

Dear Scarlett,

Sorry about the way things ended tonight. I hopeyou’re still speaking to me. If you are, would youlike to go up the pier or something tomorrow? I’llbe in the kitchen at half past nine.

Yours sincerely,

Jonathan

He had written it last night! And he had come over to her room to deliver it in spite of that cow, his mother. Scarlett put her thumbs in her ears, waggled her fingers and stuck out her tongue in the general direction of the flat at the front of the pub. So much for her, the interfering old witch. She went to get washed.

The bathroom was as repellent as the rest of the staff accommodation. The lino on the floor was curled and cracked, the bath and basin had brown stains on them where the taps dripped, there was green mould growing in one of the corners and there were notices taped up, all written in fierce black capitals:

Leave this room as you would wish to find it. Staff are allowed one bath a week. Do not waste the toilet paper. No more than three inches of water allowed in the bath.

Scarlett flushed several lots of paper down the toilet and washed under a running hot tap.

Once she was dressed, Scarlett thought she had better see how her father was. She tapped on his door, got no answer, knocked harder and finally opened it and put her head round. Victor was still asleep. She was just about to close the door again when he woke up with a start.

‘What? I didn’t…oh, Scarlett, it’s you, love. Come in. What’s the time?’

‘Half past eight.’

‘Oh—thank God. For a moment I thought…I got to be downstairs by half nine. Mustn’t be late, not for my first full day.’

He felt for his packet of cigarettes and lit one up to help him face the morning.