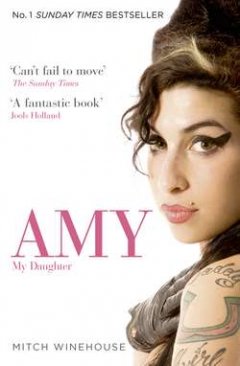

Amy, My Daughter

Àâòîð:Mitch Winehouse

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:1200.93 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 233

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 1200.93 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Amy, My Daughter

Mitch Winehouse

As an artist, she had few peers. Her lyrical prowess and timeless contralto vocals made her an instant revelation when her debut album Frank was released in 2003. And as her star continued to rise it became evident that this seemingly delicate girl from north London was much more than just a precocious talent.Genius, inspiration, icon; there are many ways to describe Amy Winehouse, but it was her wit, charm and lust for life that cemented her place in the hearts of her fans.Here, using exclusive extracts from his own personal diaries, Amy’s father and confidant Mitch celebrates what influenced his daughter. Documenting her early years from Sylvia Young to the Brit School, and the darker side of her life as she struggled to cope with her addictions under the glare of the media spotlight, he gives new insights.With never before seen photos, notes and drawings, this book brings together the many layers of Amy’s life – the personal, the private and the public – to create an honest and intensely moving account of the life of the most talented recording artist of her generation.

AMY

MY DAUGHTER

MITCH WINEHOUSE

All author proceeds from this book will be donated to the Amy Winehouse Foundation.

The Amy Winehouse Foundation has been set up in Amy’s memory to support charitable activities in both the UK and abroad that provide help, support or care for young people, especially those who are in need by reason of ill health, disability, financial disadvantage or addiction.

www.amywinehousefoundation.org (http://www.amywinehousefoundation.org)

Dedication (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

This book is dedicated to my father Alec, my mother Cynthia and my daughter Amy. They showed me that love is the most powerful force in the universe.

Love transcends even death.

They will live in my heart forever.

Contents

Title Page (#ua61cf549-c923-58bf-983b-a48ad0f65690)

Dedication

BEFORE WE START

THANKS, AND A NOTE

PROLOGUE

1 - ALONG CAME AMY

2 - TAKING TO THE STAGE

3 - ‘WENN’ SHE FELL IN LOVE

4 - FRANK – GIVING A DAMN

5 - A PAIN IN SPAIN

6 - FADE TO BLACK

7 - ‘RONNIE SPECTOR MEETS THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN’

8 - ATTACK AND THE ‘PAPS’

9 - HOOKED

10 - A BROKEN RECORD

11 - BIRMINGHAM 2007

12 - ‘AGAIN, SHE’S FINE, THANKS FOR ASKING’

13 - PRESS, LIES, AND A VIDEOTAPE

14 - DRUGS – THE ROCKY ROAD TO RECOVERY

15 - CLASS-A MUG STILL TAKING DRUGS

16 - ‘IT AIN’T BLOODY FUNNY’

17 - BEACHED

18 - ‘I’LL CRY IF I WANT TO’

19 - ‘BODY AND SOUL’

20 - ‘GIVE ME A CUDDLE, DAD’

21 - FAREWELL, CAMDEN TOWN

EPILOGUE

A NOTE ON THE AMY WINEHOUSE FOUNDATION

Photographic Insert

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

BEFORE WE START (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

You’ll understand if I tell you this is not the book I wanted to write. I had been working on one about my family’s history with my friend Paul Sassienie and his writing partner Howard Ricklow. It was due to be published this year.

I needed to write this book instead. I needed to tell you the real story of Amy’s life. I’m a plain-talking guy and I’ll be telling it like it was. Amy’s too-short life was a roller-coaster ride; I’m going to tell you about all of it. Apart from being her father, I was also her friend, confidant and adviser – not that she always took my advice, but she always heard me out. For Amy, I was the port in the storm; for me, she – along with her brother Alex – was the light of my life.

I hope, through reading this book, that you will gain a better understanding of and a new perspective on my darling daughter Amy.

THANKS, AND A NOTE (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

A huge thank-you to my wife Jane, for being my rock during the most difficult time of my life and for her continuing dedication and support; Alex, my son, for his love and understanding; Janis, for being a fantastic mother to our children; my sister Melody and all my wonderful family and friends, for always being there; my manager Trenton; my PA Megan; Raye and everyone at Metropolis; my agents Maggie Hanbury and Robin Straus, and the lovely people at HarperCollins on both sides of the Atlantic. And special thanks to Paul Sassienie, Howard Ricklow and Humphrey Price for helping me write this book.

I am donating all of my proceeds as author from this book to the Amy Winehouse Foundation, which we, Amy’s family, established to help children and young adults facing difficulty and adversity in their lives. I intend to spend the rest of my life raising money for the Foundation.

I believe that through her music, the Foundation’s work and this book, Amy will be with us for ever.

PROLOGUE (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

I’d like to say that the first time I cuddled my new-born baby daughter, on 14 September 1983, was a moment that will live with me always, but it wasn’t nearly as straightforward as that.

Some days time drags, and others the hours just fly. That day was one of those, when everything seemed to happen at once. Unlike our son Alex, who’d been born four years earlier, our daughter came into the world quickly, popping out in something of a rush, like a cork from a bottle. She arrived in typical Amy fashion – kicking and screaming. I swear she had the loudest cry of any baby I’ve ever heard. I’d like to tell you that it was tuneful but it wasn’t – just loud. Amy was four days late, and nothing ever changed: for the whole of her life she was always late.

Amy was born at the Chase Farm Hospital in Enfield, north London, not far from where we lived in Southgate. And because the moment itself was quickly over, her family – grandparents, great-aunts, uncles and cousins – soon crowded in, much as they did for almost every event in our family, good or bad, filling the spaces around Janis’s bed to greet the new arrival.

I’m a very emotional guy, especially when it comes to my family, and, holding Amy in my arms, I thought, I’m the luckiest man in the world. I was so pleased to have a daughter: after Alex was born, we’d hoped our next child might be a girl, so he could have a sister. Janis and I had already decided what to call her. Following a Jewish tradition, we gave our children names that began with the same initial as a deceased relative, so Alex was named after my father, Alec, who’d died when I was sixteen. I’d thought that if we had another boy he’d be called Ames. A jazzy kind of name. ‘Amy,’ I said, thinking that didn’t sound quite as jazzy. How wrong I was. So Amy Jade Winehouse – Jade after my stepfather Larry’s father Jack – she became.

Amy was beautiful, and the spitting image of her older brother. Looking at pictures of the two of them at that age, I find it difficult to tell them apart. The day after she was born I took Alex to see his new little sister, and we took some lovely pictures of the two of them, Alex cuddling Amy.

I hadn’t seen those photographs for almost twenty-eight years, until one day in July 2011, the day before I was due to go to New York, I got a call from Amy. I could tell right away that she was very excited.

‘Dad, Dad, you’ve got to come round,’ she said.

‘I can’t, darling,’ I told her. ‘You know I’ve got a gig tonight and I’m flying off early in the morning.’

She was insistent. ‘Dad, I’ve found the photographs. You’ve got to come round.’ Suddenly I knew why she was so excited. At some point during Amy’s numerous moves, a box of family photographs had been lost, and she had clearly come across it that morning. ‘You’ve got to come over.’

In the end I drove over in my taxi to Camden Square and parked outside her house. ‘I’m just popping in,’ I said, knowing full well how hard it was to say no to her. ‘You know I’m busy today.’

‘Oh, you’re always going too quick,’ she responded. ‘Dad, stay.’

I followed her in, and she had the photographs she’d found spread out on a table. I looked down at them. I had better ones but these obviously meant a lot to her. There was Alex holding new-born Amy, and there was Amy as a teenager – but all the rest were of family and friends.

She picked up a photo of my mum. ‘Wasn’t Nan beautiful?’ she said. Then she held up the picture of Alex and herself. ‘Oh, look at him,’ she added, a mixture of pride and sibling rivalry in her voice.

She went through the collection, picking up one after another, talking to me about each one, and I thought, This girl, famous all over the world, someone who’s brought joy to millions of people – she’s just a normal girl who loves her family. I’m really proud of her. She’s a great kid, my daughter.

It was easy to be with her that day: she was a lot of fun. Eventually, after an hour or so, it was time for me to go, and we hugged. As I held her I could feel that she was her old self: she was becoming strong again – she’d been working with weights in the gym she’d put into her house.

‘When you’re back, we’ll go into the studio to do that duet,’ she said, as we walked to the door. We had two favourite songs, ‘Fly Me To The Moon’ and ‘Autumn Leaves’, and Amy wanted us to record one or other of them together. ‘We’re going to rehearse properly,’ she added.

‘I’ll believe it when I see it,’ I said, laughing. We’d had this conversation many times over the years. It was nice to hear her talking like that again. I waved goodbye out of the cab.

I never saw my darling daughter alive again.

* * *

I arrived in New York on the Friday, and had a quiet evening alone. The following day I went to see my cousin Michael and his wife Alison at their apartment on 59th Street – Michael had immigrated to the US a few years earlier when he’d married Alison. They now had three-month-old twins, Henry and Lucy, and I was dying to meet them. The kids were great and I had Henry sitting on my lap when Michael got a call from his father, my uncle Percy, who lives in London. Michael passed the phone to me. There was the usual stuff: ‘Hello, Mitch, how are you? How’s Amy?’ I told him I’d seen Amy just before I’d flown out and she was fine.

My mobile rang. The caller ID said, ‘Andrew – Security’. Amy often rang me using the phone of her security guard Andrew so I told my uncle, ‘I think that’s Amy now,’ and passed the house phone back to Michael. I still had Henry on my lap as I answered my phone.

‘Hello, darling,’ I said. But it wasn’t Amy, it was Andrew. I could barely make out what he was saying.

All I could decipher was: ‘You gotta come home, you gotta come home.’

‘What? What are you talking about?’

‘You’ve got to come home,’ he repeated.

My world drained away from me. ‘Is she dead?’ I asked.

And he said, ‘Yes.’

1 ALONG CAME AMY (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

From the start I was besotted with my new daughter, and not much else mattered to me. In the days before Amy was born, I’d been fired from my job, supposedly because I’d asked to take four days off for my daughter’s birth. But with Amy in the world those concerns seemed to disappear. Even though I had no job, I went out and bought a JVC video camera, which cost nearly a grand. Janis wasn’t best pleased, but I didn’t care. I took hours of video of Amy and Alex, which I’ve still got.

Alex sat guard by her cot for hours at a time. I went into her bedroom late one night and found Amy wide awake and Alex fast asleep on the floor. Great guard he made. I was a nervous dad, and I’d often peer into her cot to check she was okay. When she was a very young baby I’d find her panting, and shout, ‘She’s not breathing properly!’ Janis had to explain that all babies made noises like that. I still wasn’t happy, though, so I’d pick Amy up – and then we couldn’t get her back to sleep. She was an easy baby, though, and it wasn’t long before she was sleeping through the night, so soundly sometimes that Janis had to wake her up to feed her.

Amy learned to walk on her first birthday, and from then on she was a bit of a handful. She was very inquisitive, and if you didn’t watch her all the time, she’d be off exploring. At least we had some help: my mother and stepfather, along with most of the rest of my family, seemed to be there every day. Sometimes I’d come home late from work and Janis would tell me they’d eaten my dinner.

Janis was a wonderful mother, and still is. Alex and Amy could both read and write before they went to school, thanks to her. When I came home I’d hear them upstairs, walk up quietly and stand outside their bedroom door to watch them. The kids would be tucked in either side of Janis as she read to them, their eyes wide, wondering what was coming next. This was their time together and I wished I was part of it.

On the nights that I didn’t get home until ten or eleven o’clock, I’d sometimes wake them up to say goodnight. I’d go into their room, kick the cot or bed, say, ‘Oh, they’re awake,’ and pick them up for a cuddle. Janis used to go mad and quite right too.

I was a hands-on father but more for rough-and-tumble than reading stories. Alex and I would play football and cricket in the garden, and Amy would want to join in – ‘Dad! Dad! Give me the ball.’ I’d prod it towards her, then she’d pick it up and throw it over the fence.

Amy loved dancing and, as most dads did with their young daughters, I’d hold her hands and balance her feet on mine. We’d sway like that around the room, but Amy liked it best when I twirled her round and round, enjoying the feeling of disorientation it gave her. She became fearless physically, climbing higher than I liked, or rolling over the bars of a climbing frame in the park. She also liked playing at home: she loved her Cabbage Patch dolls, and we had to send off the ‘adoption certificates’ the dolls came with to keep her happy. If Alex wanted to torment her, he’d tie the dolls up.

When I did come home early I read to the children, always Enid Blyton’s Noddy books. Amy and Alex were Noddy experts. Amy loved the ‘Noddy quiz’.

She would say, ‘Daddy, what was Noddy wearing the day he met Big Ears?’

I’d pretend to think for a minute. ‘Was he wearing his red shirt?’

Amy would say, ‘No.’

I’d tell her that was a very hard question and I needed to think. ‘Was he wearing his blue hat with the bell on the end?’ Another no. Then I’d click my fingers. ‘I know! He was wearing his blue shorts and his yellow scarf with red spots.’

‘No, Daddy, he wasn’t.’

At that point I’d give in and ask Amy to tell me what he was wearing. Before she could get the words out, she was already giggling. ‘He wasn’t wearing anything, he was … naked!’

And then she’d put her hand over her mouth to stifle her hysterical laughing. No matter how many times we played that game it never varied.

We weren’t one of those families that had the TV on for the sake of it. There was always music playing and I sang around the house. We used to get the kids to put on little shows for us. I’d introduce them and Janis would clap and they’d start singing – well, I say singing … Alex couldn’t sing but would give it a go, and Amy’s only goal was to sing louder than her brother. Clearly she liked the limelight. If Alex got bored and went off to do something else, Amy would carry on singing – even after we’d told her to stop.

She loved a little game I used to play with her – we did it a lot in the car. I’d start a song or nursery rhyme and she’d sing the last word.

‘Humpty Dumpty sat on the …’

‘… WALL …’

‘… Humpty Dumpty had a great …’

‘… FALL.’ It kept us amused for ages.

One year Amy was given a little turntable that played nursery rhymes. It was all you heard from her room. Then she had a xylophone and taught herself – slowly and painfully – to play ‘Home On The Range’. The noise would carry through the house, plink, plink, plink, and I’d will her to hit the right notes on time – it was agonizing to have to listen to it.

Despite her charm, ‘Be quiet, Amy!’ was probably the most-heard sentence in our house during her early years. She just didn’t know when to stop. Once she started singing that was it. And if she wasn’t the centre of attention, she’d find a way of becoming it – occasionally at Alex’s expense. At his sixth birthday party Amy, aged two, put on an impromptu show of singing and dancing. Naturally, Alex wasn’t best pleased and, before we could stop him, he poured a drink over her. Amy burst into tears and ran out of the room crying. I shouted at Alex so loudly that he ran out crying too. After the party, Amy sat on the kitchen floor sulking, and Alex wouldn’t come out of his room.

Despite such scenes, Alex and Amy were extremely close and remained so, even when they got older and made their own circles of friends.

Amy would do anything for attention. She was mischievous, bold and daring. Not long after Alex’s birthday party, Janis took Amy to Broomfield Park, near our home, and lost her. A panic-stricken Janis phoned me at work to tell me that Amy was missing and I raced to the park, beside myself with anxiety. By the time I arrived, the police were there and I was preparing myself for the worst: in my mind, she wasn’t lost, she’d been abducted. My mum and my auntie Lorna were also there – everybody was looking for Amy. Clearly, Amy was no longer in the park and the police told us to go home, which we did. Five hours later, Janis and I were crying our eyes out when the phone rang. It was Ros, one of my sister Melody’s friends. Amy was with her. Thank God.

What had happened was just typical of Amy. Ros had been in the park with her kids when Amy had seen her and run over to her. Naturally, Ros had asked where her mummy was, and mischievous Amy had told her that her mummy had gone home. So Ros took Amy home with her, but instead of phoning us, she phoned Melody, who was a teacher. She didn’t speak to her but left a message at the school that Amy was with her. When Melody heard that Ros was looking after Amy, she didn’t think too much about it because she had no idea that Amy was missing. When she got home and heard what had happened, she put two and two together. Fifteen minutes later, Melody walked in with Amy and I burst into tears.

‘Don’t cry, Daddy, I’m home now,’ I remember her saying.

Unfortunately, Amy didn’t seem to learn from that experience. Several months later I took the kids to the Brent Cross shopping centre in north-west London. We were in the John Lewis department store and suddenly Amy was gone. One second she was there and the next she’d disappeared. Alex and I searched the immediate area – how far could she have got? – but there was no sign of her. Here we go again, I thought. And this time she’d definitely been kidnapped.

We widened the search. Just as we were walking past a rack of long coats, out she popped. ‘Boo!’ I was furious, but the more I told her off, the more she laughed. A few weeks later she tried it again. This time I headed straight for the long coats. She wasn’t there. I searched all of the racks. No Amy. I was really beginning to worry when a voice said over the Tannoy, ‘We’ve got a little girl called Amy here. If you’ve lost her, please come to Customer Services.’ She’d hidden somewhere else, got really lost and someone had taken her to a member of staff. I told her there was to be no more hiding or running away when we’re out. She promised she wouldn’t do it again and she didn’t, but the next series of practical jokes was played out to a bigger audience.

When I was a little boy I had choked on a bit of apple and my father had panicked. So, when Alex choked on his dinner, I panicked too, forcing my fingers down his throat to remove whatever was obstructing him. It didn’t take Amy long to start the choking game. One Saturday afternoon we were shopping in Selfridges, in London’s Oxford Street. The store was packed. Suddenly Amy threw herself on to the floor, coughing and holding her throat. I knew she wasn’t really choking but she was creating such a scene that I threw her over my shoulder and we left in a hurry. After that she was ‘choking’ everywhere, friends’ houses, on the bus, in the cinema. Eventually, we just ignored it and it stopped.

* * *

Although I was born in north London, I’ve always considered myself to be an East Ender: I spent a lot of my childhood with my grandparents, Ben and Fanny Winehouse, at their flat above Ben the Barber, his business, in Commercial Street, or with my other grandmother, Celie Gordon, at her house in Albert Gardens, both in the heart of the East End. I even went to school in the East End. My father was a barber and my mother was a ladies’ hairdresser, both working in my grandfather’s shop, and, on their way there, they’d drop me off at Deal Street School.

Amy and Alex were fascinated by the East End so I took them there often. They loved me to tell them stories about our family, and seeing where they had lived brought the stories to life. Amy liked hearing about my weekends in the East End when I was a little boy. Every Friday I went with my mum and dad to Albert Gardens where we’d stay until Sunday night. The house was packed to the rafters. There was Grandma Celie, Great-grandma Sarah, Great-uncle Alec, Uncle Wally, Uncle Nat, and my mum’s twin, Auntie Lorna. If that wasn’t enough, a Holocaust survivor named Izzi Hammer lived on the top floor; he passed away in January 2012.

The weekends at Albert Gardens started with the traditional Jewish Friday night dinner: chicken soup, then roast chicken, roast potatoes, peas and carrots. Dessert was lokshen pudding, made with baked noodles and raisins. Where all those people slept I really can’t remember, but we all had a magical time, with singing, dancing, card games, and loads of food and drink. And the occasional loud argument mixed in with the laughter and joy of a big happy Jewish family. We continued the Friday-night tradition for most of Amy’s life. It was always a special time for us, and in later years, an interesting test of Amy’s friendships – who was close enough to her to be invited on a Friday night.

I spent a lot of time with the kids at weekends. In February 1982, when Alex was nearly three, I started taking him to watch football – in those days you could take young kids and sit them on your lap: Spurs v. West Bromwich Albion. It was freezing cold, so cold that I didn’t want to go, but Janis dressed Alex in his one-piece padded snowsuit, which made him look twice his size – he could hardly move. When we got there I asked him if he was okay. He said he was. About five minutes after kick-off he wanted to go to the Gents. Getting him out of that padded suit was quite an operation, and then it took another ten minutes to get him into it again. When we got back to the seat, he needed to go again so we had an action replay. At half-time, he said, ‘Daddy I want to go home – I’m home-sick.’

When Amy was about seven, I took her to a match. When we got home Janis asked her if she’d enjoyed it. Amy said she’d hated it. When Janis asked why she hadn’t asked me to bring her home, she said, ‘Daddy was enjoying it and I didn’t want to upset him.’ That was typical of the young Amy, always thinking of other people.

At five Amy started at Osidge Primary School, where Alex was already a pupil. There she met Juliette Ashby, who quickly became her best friend. Those two were inseparable and remained close for most of Amy’s life. Her other great friend at Osidge was Lauren Gilbert: Amy already knew her because Uncle Harold, my dad’s brother, was Lauren’s step-grandfather.

Amy had to wear a light-blue shirt and a tie, with a sweater and a grey skirt. She was happy to join her big brother at school, but she was soon in trouble. Every day she was there could easily have been her last. She didn’t do anything terrible but she was disruptive and attention-seeking, which led to regular complaints about her behaviour. She wouldn’t be quiet in lessons, she doodled in her books and she played practical jokes. Once she hid under the teacher’s desk. When he asked the class where Amy was, she was laughing so much that she bumped her head on his desk and had to be brought home.

Amy left a lasting impression on her Year Two teacher, Miss Cutter (now Jane Worthington), who wrote to me shortly after Amy passed away:

Amy was a vivacious child who grew into a beautiful and gifted woman. My lasting memories of Amy are of a child who wore her heart on her sleeve. When she was happy the world knew about it, when upset or unhappy you’d know that too. It was clear that Amy came from a loving and supportive family.

Amy was a clever girl, and if she’d been interested she would have done well at school. Somehow, though, she was never that interested. She was good at things like maths, but not in the sense that she did well at school. Janis was really good at maths and used to teach the kids. Amy loved doing calculus and quadratic equations when she was still at primary school. No wonder she found maths lessons boring.

She was always interested, though, in music. I always had it playing at home and in the car, and Amy sang along with everything. Although she loved big-band and jazz songs, she also liked R&B and hip-hop, especially the US R&B/hip-hop bands TLC and Salt-n-Pepa. She and Juliette used to dress up like Wham!’s backing singers, Pepsi & Shirlie, and sing their songs. When Amy was about ten she and Juliette formed a short-lived rap act, Sweet ’n’ Sour – Juliette was Sweet and Amy was Sour. There were a lot of rehearsals but, sadly, no public performances.

I was devoted to my family, but as Amy and Alex got older, I was changing. In 1993, Janis and I split up. A few years earlier, a close friend of mine, who was married, confided in me that he was seeing someone else. I couldn’t understand how he could do it. I remember telling him that he had a lovely wife and a fantastic son: why on earth would he want to jeopardize everything for a fling? He said, ‘It’s not a fling. When you find that special someone you just know it’s right. If it ever happens to you, you’ll understand.’

Unbelievably I found myself in a similar situation. Back in 1984 I had appointed a new marketing manager, Jane, and we had hit it off from the start. There was nothing romantic: Jane had a boyfriend and I was happily married. But there was definitely a spark between us. Nothing happened for ages and then eventually it did. Jane had been coming to my house since Amy was eighteen months old and had met Janis and the kids loads of times. She was adamant that she didn’t want to come between me and my family.

I was in love with Jane but still married to Janis. That’s a situation which just can’t work indefinitely. It was a terrible dilemma. I wanted to be with Janis and the kids but I also wanted to be with Jane. I was never unhappy with Janis and we had a good marriage. Some men who stray hate their wives but I loved mine. You couldn’t have an argument with her if you tried: she’s such a sweet, good-natured person. I didn’t know what to do. I really didn’t want to hurt anybody. In the end I just wanted to be with Jane more.

Finally, in 1992, I made up my mind to leave Janis. I would wait until after Alex had had his Bar Mitzvah the following year, and leave shortly afterwards. Telling Alex and Amy was the hardest thing; I explained that we both loved them and that what was happening was nothing to do with anything they’d done or not done. Alex took it very badly – who can blame him? – but Amy seemed to accept it.

I felt awful as I drove away to live with Melody in Barnet. I stayed with her for six months before I moved in with Jane. Looking back now, I was a coward for allowing the situation to go on for so long, but I wanted to keep everybody happy.

Strangely, after I left I started seeing more of the kids than I had before. My friends thought that Amy didn’t seem much affected by the divorce, and when I asked her if she wanted to talk about it, she said, ‘You’re still my dad and Mum’s still my mum. What’s to talk about?’

Probably through guilt, I over-indulged them. I’d buy them presents for no reason, take them to expensive places and give them money. Sometimes, when I was starting a new business and things were tight, we’d go and eat at the Chelsea Kitchen in the King’s Road where I could buy meals for no more than two pounds. Years later, the kids told me they’d liked going there better than the more expensive places, mostly because they knew it wasn’t costing me a lot.

Two things never changed: my love for them and theirs for me.

Amy in a contemplative mood. My birthday card in 1992.

2 TAKING TO THE STAGE (#uf17f966f-0d90-50ab-b238-fb1dc464ab5e)

Wherever I was living, Amy and Alex always had a bedroom there. Amy would often stay for the weekend and I’d try to make it special for her. She loved ghost stories: when I lived in Hatfield Heath, Essex, the house was a bit remote and quite close to a graveyard. If we were driving home on a dark winter’s night I used to park near the graveyard, turn the car lights off and frighten the life out of her with a couple of grisly stories. It wasn’t long before she started making up ghost stories of her own, and I had to pretend to be scared.

On one occasion Amy had to write an essay about the life of someone who was important to her. She decided to write about me and asked me to help her. It had to be exciting, I decided, so I made up some stories about myself but Amy believed them all. I told her I’d been the youngest person to climb Mount Everest, and that when I was ten I’d played for Spurs and scored the winning goal in the 1961 Cup Final against Leicester City. I also told her I’d performed the world’s first heart transplant with my assistant Dr Christiaan Barnard. I might also have told her I’d been a racing driver and a jockey.

Amy took notes, wrote the essay and handed it in. I was expecting some nice remarks about her imagination and sense of humour, but instead the teacher sent me a note, saying, ‘Your daughter is deluded and needs help.’ Not long before Amy passed away, she reminded me about that homework and the trouble it had caused – and she remembered another of my little stories, which I’d forgotten: I’d told her and Alex that when I was seven I’d been playing near Tower Bridge, fallen into the Thames and nearly drowned. I even drove them to the spot to show them where it had supposedly happened and told them there used to be a plaque there commemorating the event but they had taken it down to clean it.

During school holidays we had to find things for Amy to do. If I was in a meeting, Jane would take her out for lunch and Amy would always order the same thing: a prawn salad. The first time Jane took her out, when Amy was still small, she asked, ‘Would you like some chocolate for pudding?’

‘No, I have a dairy intolerance,’ said Amy, proudly. She’d then wolfed down bag after bag of boiled sweets and chews – she always had a sweet tooth.

Jane used to work as a volunteer on the radio at Whipps Cross Hospital, and had her own show. Amy would go in with her to help. She was too young to go round the wards when Jane was interviewing the patients, so instead she would choose the records that were going to be played. Once Jane interviewed Amy, and I’ve still got the tapes of that conversation somewhere. Jane edited out her questions so that Amy was speaking directly to the listeners – her first broadcast.

One link I never lost with Amy when I left home was music. She learned to love the music I had been taught to love by my mother when I was younger. My mum had always adored jazz, and before she met my father she had dated the great jazz musician Ronnie Scott. At a gig in 1943, Ronnie introduced her to the legendary band leader Glenn Miller, who tried to nick her off Ronnie. And while my mum fell in love with Glenn Miller’s music, Ronnie fell in love with her. He was devastated when she ended the relationship. He begged her not to and even proposed to her. She said no, but they remained close friends right up until he died in 1996. He wrote about my mum in his autobiography.

When she was a little girl, Amy loved hearing my mother recount her stories about Ronnie, the jazz scene and all the things they’d got up to. As she grew up she started to get into jazz in a big way; Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan were her early favourites.

Amy loved one particular story I told her about Sarah Vaughan and Ronnie Scott. Whenever Ronnie had a big name on at his club, he would always invite my mum, my auntie Lorna, my sister, me and whoever else we wanted to bring. We saw some fantastic acts there – Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and a whole host of others – but for me, the most memorable was Sarah Vaughan. She was just wonderful. We went backstage afterwards and there was a line of about six people waiting to be introduced to her. When it was Mum’s turn, Ronnie said, ‘Sarah, this is Cynthia. She was my childhood sweetheart and we’re still very close.’

Then it was my turn. Ronnie said, ‘This is Mitch, Cynthia’s son.’

And Sarah said, ‘What do you do?’

I told her about my job in a casino and we carried on chatting for a couple of minutes about one thing and another.

Then Ronnie said, ‘Sarah, this is Matt Monro.’

And Sarah said, ‘What do you do, Matt?’

She really had no idea who he was. American singers are often very insular. A lot of them don’t know what’s happening outside New York or LA, let alone what’s going on in the UK. I felt a bit sorry for Matt because he was, in my opinion, the greatest British male singer of all time – and he wasn’t best pleased either. He walked out of the club and never spoke to Ronnie Scott again.

Amy also started watching musicals on TV – Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly films. She preferred Astaire, whom she thought more artistic than the athletic Kelly; she enjoyed Broadway Melody of 1940, when Astaire danced with Eleanor Powell. ‘Look at this, Dad,’ she said. ‘How do they do it?’ That sequence gave her a love of tap-dancing.

Amy would regularly sing to my mum, and my mum’s face would light up when she did. As Amy’s number-one adoring fan, who always thought Amy was going to be a star, my mum came up with the idea of sending nine-year-old Amy to the Susi Earnshaw Theatre School, in Barnet, north London, not far from where we lived. It offered part-time classes in the performing arts for five- to sixteen-year-olds. Amy used to go on Saturdays and this was where she first learned to sing and tap-dance.

Amy looked forward to those lessons and, unlike at Osidge, we never received a complaint about her behaviour from Susi Earnshaw’s. Susi told us how hard Amy always worked. Amy was taught how to develop her voice, which she wanted to do as she learned more and more about the singers she listened to at home and with my mum. Amy was fascinated by the way Sarah Vaughan used her voice like an instrument and wanted to know how she could do it too.

As soon as she started at Susi Earnshaw’s, Amy was going for auditions. When she was ten she went to one for the musical Annie; Susi sent quite a few girls for that. She told me that Amy wouldn’t get the part, but it would be good for her to gain experience in auditioning – and get used to rejection.

I explained all of that to Amy but she was still happy to go along and give it a go. The big mistake I made was in telling my mum about it. For whatever reason, neither Janis nor I could take Amy to the audition and my mum was only too pleased to step in. As Amy’s biggest fan, she thought this was it, that the audition was a formality – that her granddaughter was going to be the new Annie. I think she even bought a new frock for the opening night, that was how sure she was.

When I saw Amy that night, the first thing she said to me was, ‘Dad, never send Nan with me for an audition ever again.’

It had started on the train, my mum piling on the pressure: how to sing her song, how to talk to the director, ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that, look the director in the eye …’ Amy had been taught all of this at Susi Earnshaw’s but, of course, my mum knew better. They finally got to the theatre where, according to Amy, there were a thousand or so mums, dads and grandmothers, each of whom, like my mum, thought that their little prodigy was going to be the new Annie.

Finally it was Amy’s turn to do her bit and she gave the audition pianist her music. He wouldn’t play it: it was in the wrong key for the show. Amy struggled through the song in a key that was far too high for her. After just a few bars she was told to stop. The director was very nice and thanked her but told her that her voice wasn’t suitable for the part. My mum lost it. She marched up to the director, screaming at him that he didn’t know what he was talking about. There was a terrible row.

On the train going home my mum had a go at Amy, all the usual stuff: ‘You don’t listen to me. You think you know better …’ Amy couldn’t have cared less about not getting the part, but my mum was so aggravated that she put herself to bed for the rest of the day. When Amy told me the story, I thought it was absolutely hysterical. My mum and Amy were like two peas in a pod, probably shouting at each other all the way home on the train.

It would have been a great scene to see.

Amy and my mum had a lively relationship but they did love each other, and my mum would sometimes let the kids get away with murder. When we visited her, Amy would often blow-wave my mum’s hair while Alex sat at her feet and gave her a pedicure. Later my mum, hair all over the place, would show us what Amy had done and we’d have a good laugh.

* * *

In the spring of 1994, when Amy was ten, I went with her to an interview for her next school, Ashmole in Southgate. I had gone there some twenty-five years earlier and Alex was there so it was a natural choice for Amy. Incredibly, my old form master Mr Edwards was still going strong and was to be Amy’s house master. He interviewed Amy and me when I took her to look round the school. We walked into his office and he recognized me immediately. In his beautiful Welsh accent, he said, ‘Oh, my God, not another Winehouse! I bet this one doesn’t play football.’ I had made a bit of a name for myself playing for the school, and Alex was following in my footsteps.

Amy started at Ashmole in September 1994. From the start she was disruptive. Her friend Juliette had also transferred there. They were bad enough alone, but together they were ten times worse, so it wasn’t long before they were split up and put into different classes.

Alex had a guitar he’d taught himself to play, and when Amy decided to try it out he taught her too. He was very patient with her, even though they argued a lot. They could both read music, which surprised me. ‘When did you learn to do this?’ I asked. They stared at me as if I was speaking a foreign language. Amy soon started writing her own songs, some good, some awful. One of the good ones was called ‘I Need More Time’. She played it for me just a few months before she passed away. Believe me, it’s good enough to go on one of her albums, and it’s a great pity that she never recorded it.

I often collected the kids from school. In those days I had a convertible, and Amy would insist I put the top down. As we drove along, Alex in the front alongside me, she’d sing at the top of her voice. When we stopped at traffic lights she would stand up and perform. ‘Sit down, Amy!’ we’d say, but people on the street laughed with her as she sang.

Once she was in a car with a friend of mine named Phil and sang ‘The Deadwood Stage’ from the Doris Day film Calamity Jane. ‘You know,’ Phil said to me, when they got back, his ears probably still ringing, ‘your daughter has a really powerful voice.’

Amy’s wild streak went far beyond car rides. At some point, she took to riding Alex’s bike, which terrified me: she was reckless whenever she was on it. She had no road sense and she raced along as fast as she could. She loved speed and came off a couple of times. It was the same story when I took her skating – didn’t matter if it was ice-skating or roller-skating, she loved both. She was really fast on the rink, and the passion for it never left her. After her first album came out she told me that her ambition was to open a chain of hamburger joints with roller-skating waitresses.

She was wild, but I indulged her; I couldn’t help myself. I know I over-compensated my children for the divorce, but they were growing up and needed things. I took Amy shopping to buy her some clothes, now that she was nearly a teenager and going to a new school.

‘Look, Dad,’ she said excitedly, as she came out of the changing room in a pair of leopard-print jeans. ‘These are fantastic! D’you think they look nice on me?’

* * *

Whenever she was staying with Jane and me, Amy always kept a notebook with her to scribble down lines for songs. Halfway through a conversation, she’d suddenly say, ‘Oh, just a sec,’ and disappear to note something that had just come to her. The lines looked like something from a poem and later she would use those lines in a song, alongside ones written on totally different occasions.

Amy continued to be good at maths because of the lessons she’d done with her mother. Janis would set Amy some pretty complicated problems, which she really enjoyed doing. Amy would do mathematical problems for hours on end just for fun. She was brilliant at the most complex Sudoku puzzles and could finish one in a flash.

The pity was that she wouldn’t do it at school. We received notes complaining regularly about her behaviour or lack of interest. Clearly Amy was bored – she just didn’t take to formal schooling. (I had been the same. I was always playing hooky but, unlike my friends, who would be out on the streets, I’d be in the local library, reading.) Amy had a terrific thirst for knowledge but hated school. She didn’t want to go so she wouldn’t get up in the mornings. Or, if she did go, she’d come home at lunchtime and not go back.

Though Amy had been a terrific sleeper as a baby and young child, when she got to about eleven she wouldn’t go to bed: she’d be up all night reading, doing puzzles, watching television, listening to music, anything not to go to sleep. So, naturally, it was a battle every morning to get her up. Janis got fed up with it and would ring me: ‘Your daughter won’t get out of bed.’ I had to drive all the way from Chingford, where I was living with Jane, and drag her out.

Over time Amy got worse in the classroom. Janis and I were called to the school for meetings about her behaviour on numerous occasions. I hope the head of year didn’t see me trying not to laugh as he told us, ‘Mr and Mrs Winehouse, Amy has already been sent to see me once today and, as always, I knew it was her before she got to my office …’ I knew if I looked at Janis I’d crack up. ‘How did I know?’ the head of year continued. ‘She was singing “Fly Me To The Moon” loudly enough for the whole school to hear.’

I knew I shouldn’t laugh, but it was so typically Amy. She told me later that she’d sung it to calm herself down whenever she knew she was in trouble.

Just about the only thing she seemed to enjoy about school was performance. However, one year when Amy sang in a show she wasn’t very good. I don’t know what went wrong – perhaps it was the wrong key for her again – but I was disappointed. The following year things were different. ‘Dad, will you both come to see me at Ashmole?’ she asked. ‘I’m singing again.’ To be honest, my heart sank a bit, with the memory of the previous year’s performance, but of course we went. She sang the Alanis Morissette song ‘Ironic’, and she was as terrific as I knew she could be. What I wasn’t expecting was everyone else’s reaction: the whole room sat up. Wow, where did this come from?

By now Amy was twelve and she wanted to go to a drama school full time. Janis and I were against it but Amy applied to the Sylvia Young Theatre School in central London without telling us. How she even knew about it we never figured out as Sylvia Young only advertised in The Stage. Amy eventually broke the news to us when she was invited to audition. She decided to sing ‘The Sunny Side Of The Street’, which I coached her through, helping with her breath control, and won a half-scholarship for her singing, acting and dancing. Her success was reported in The Stage, with a photograph of her above the column.

As part of her application, Amy had been asked to write something about herself. Here’s what she wrote:

All my life I have been loud, to the point of being told to shut up. The only reason I have had to be this loud is because you have to scream to be heard in my family.

My family? Yes, you read it right. My mum’s side is perfectly fine, my dad’s family are the singing, dancing, all-nutty musical extravaganza.

I’ve been told I was gifted with a lovely voice and I guess my dad’s to blame for that. Although unlike my dad, and his background and ancestors, I want to do something with the talents I’ve been ‘blessed’ with. My dad is content to sing loudly in his office and sell windows.

My mother, however, is a chemist. She is quiet, reserved.

I would say that my school life and school reports are filled with ‘could do betters’ and ‘does not work to her full potential’.

I want to go somewhere where I am stretched right to my limits and perhaps even beyond.

To sing in lessons without being told to shut up (provided they are singing lessons).

But mostly I have this dream to be very famous. To work on stage. It’s a lifelong ambition.

I want people to hear my voice and just forget their troubles for five minutes.

I want to be remembered for being an actress, a singer, for sell-out concerts and sell-out West End and Broadway shows.

I think it was to the school’s relief when Amy left Ashmole. She started at the Sylvia Young Theatre School when she was about twelve and a half and stayed there for three years – but what a three years it was. It was still school, which meant she was always being told off, but I think they put up with her because they recognized that she had a special talent. Sylvia Young herself said that Amy had a ‘wild spirit and was amazingly clever’. But there were regular ‘incidents’ – for example, Amy’s nose-ring. Jewellery wasn’t allowed, a rule Amy disregarded. She would be told to take the nose-ring out, which she would do, and ten minutes later it was back in.

The school accepted that Amy was her own person and gave her a degree of leeway. Occasionally they turned a blind eye when she broke the rules. But there were times when she took it too far, especially with the jewellery. She was sent home one day when she’d turned up wearing earrings, her nose-ring, bracelets and a belly-button piercing. To me, though, Amy wasn’t being rebellious, which she certainly could be; this was her expressing herself.

And punctuality was a problem. Amy was late most days. She would get the bus to school, fall asleep, go three miles past her stop, then have to catch another back. So, although this was where Amy wanted to be, it wasn’t a bed of roses for anyone.

Amy’s main problem at Sylvia Young’s was that, as well being taught stagecraft, which included ballet, tap, other dance, acting and singing, she had to put up with the academic side or, as Amy referred to it, ‘all the boring stuff’. About half of the time was allocated to ‘normal’ subjects and she just wasn’t interested. She would fall asleep in lessons, doodle, talk and generally make a nuisance of herself.

Amy really got into tap-dancing. She was pretty good at it when she started at the school but now she was learning more advanced techniques. When we were at my mother’s flat for dinner on Friday nights, Amy loved to tap-dance on the kitchen floor because it gave a really good clicking sound. The clicks it gave were great. I told her she was as good a dancer as Ginger Rogers, but my mother wouldn’t have that: she said Amy was better.

Amy would put her tap shoes on and say, ‘Nan, can I tap-dance?’

‘Go downstairs and ask Mrs Cohen if it’s all right,’ my mum would reply, ‘because you know what she’s like. She’ll only complain to me about the noise.’

So Amy would go and ask Mrs Cohen if it was all right and Mrs Cohen would say, ‘Of course it’s all right, darling. You go and dance as much as you like.’ And then the next day Mrs Cohen would complain to my mum about the noise.

After dinner on a Friday night, we’d play games. Trivial Pursuit and Pictionary were two of our favourites. Amy and I played together, my mum and Melody made up the second team, with Jane and Alex as the third. They were the ‘quiet’ ones, thoughtful and studious, my mum and Melody were the ‘loud’ pair, with a lot of screaming and shouting, while Amy and I were the ‘cheats’. We’d try to win no matter what.

Another lovely birthday card from Amy, aged twelve. This came just after yet another meeting with Amy’s teacher about her behaviour.

When she wasn’t playing games or tap-dancing, Amy would borrow my mum’s scarves and tops. She had a way of making them seem not like her nan’s things but stylish, tying shirts across her middle and that sort of thing. She also started wearing a bit of makeup – never too much, always understated. She had a beautiful complexion so she didn’t use foundation, but I’d spot she was wearing eyeliner and lipstick – ‘Yeah, Dad, but don’t tell Mum.’

But while my mum indulged Amy’s experiments with makeup and clothes, she hated Amy’s piercings. Later on when Amy began getting tattoos, she’d have a go at her about all of it. Amy’s ‘Cynthia’ tattoo came after my mum had passed away – she would have loathed it.

* * *

Along with other pupils from Sylvia Young’s, Amy started getting paid work around the time she became a teenager. She appeared in a sketch on BBC2’s series The Fast Show; she stood precariously on a ladder for half an hour in Don Quixote at the Coliseum in St Martin’s Lane (she was paid eleven pounds per performance, which I’d look after for her as she always wanted to spend it on sweets); and in a really boring play about Mormons at Hampstead Theatre where her contribution was a ten-minute monologue at the end. Amy loved doing the little bits of work the school found for her, but she couldn’t accept that she was still a schoolgirl and needed to study.

Eventually Janis and I were called in to see the head teacher of the school’s academic side, who told us he was very disappointed with Amy’s attitude to her work. He said that he constantly had to pressure her to buckle down and get some work done. He accepted that she was bored and they even tried moving her up a year to challenge her more, but she became more distracted than ever.

The real blow came when the academic head teacher phoned Janis, behind Sylvia Young’s back, and told her that if Amy stayed at the school she was likely to fail her GCSEs. When Sylvia heard about this she was very upset and the head teacher left shortly afterwards.

Contrary to what some people have said, including Amy, Amy was not expelled from Sylvia Young’s. In fact, Janis and I decided to remove her as we believed that she had a better chance with her exams at a ‘normal’ school. If you’re told that your daughter is going to fail her GCSEs, then you have to send her somewhere else. Amy didn’t want to leave Sylvia Young’s and cried when we told her that we were taking her away. Sylvia was also upset and tried to persuade us to change our minds, but we believed we were doing the right thing. She stayed in touch with Amy after she’d left, which surprised Amy, given all the rows they’d had over school rules. (Our relationship with Sylvia and her school continues to this day. From September 2012, Amy’s Foundation will be awarding the Amy Winehouse Scholarship, whereby one student will be sponsored for their entire five years at the school.)

Amy had to finish studying for her GCSEs somewhere, though, and the next school to get the Amy treatment was the all-girls Mount School in Mill Hill, north-west London. The Mount was a very nice, ‘proper’ school where the students were decked out in beautiful brown school uniforms – a huge change from leg warmers and nose-rings. Music was strong there and, in Amy’s words, kept her going. The music teacher took a particular interest in her talent and helped her settle in. I use that term loosely. She was still wearing her jewellery, still turning up late and constantly rowing with teachers about her piercings, which she delighted in showing to everybody. When I remember where some of those piercings were, I’m not surprised the teachers got upset. But, one way or another, Amy got five GCSEs before she left the Mount and yet another set of breathless teachers behind her.

There was no question of her staying on for A levels. She had had enough of formal education and begged us to send her to another performing-arts school. Once Amy had made up her mind, that was it: there was no chance of persuading her otherwise.

When Amy was sixteen she went to the BRIT School in Croydon, south London, to study musical theatre. It was an awful journey to get there – from the north of London right down to the south, which took her at least three hours every day – but she stuck at it. She made lots of friends and impressed the teachers with her talent and personality. She also did better academically: one teacher told her she was ‘a naturally expressive writer’. At the BRIT School Amy was allowed to express herself. She was there for less than a year but her time was well spent and the school made a big impact on her, as did she on it and its students. In 2008, despite the personal problems she was having, she went back to do a concert for the school by way of a thank-you.

3 ‘WENN’ SHE FELL IN LOVE (#ulink_82b210c9-8b24-543d-94c2-dc9b147d9269)

As it turned out, it was a good thing that Sylvia Young stayed in touch with Amy after she left the school, because it was Sylvia who inadvertently sent Amy’s career in a whole new direction.

Towards the end of 1999, when Amy was sixteen, Sylvia called Bill Ashton, the founder, MD and life president of the National Youth Jazz Orchestra (NYJO), to try to arrange an audition for Amy. Bill told Sylvia that they didn’t audition. ‘Just send her along,’ he said. ‘She can join in if she wants to.’

So Amy went along, and after a few weeks, she was asked to sing with the orchestra. One Sunday morning a month or so later, they asked Amy to sing four songs with the orchestra that night because one of their singers couldn’t make it. She didn’t know the songs very well but that didn’t faze her – water off a duck’s back for Amy. One quick rehearsal and she’d nailed them all.

Amy sang with the NYJO for a while, and did one of her first real recordings with them. They put together a CD and Amy sang on it. When Jane and I heard it, I nearly fainted – I couldn’t believe how fantastic she sounded. My favourite song on that CD has always been ‘The Nearness Of You’. I’ve heard Sinatra sing it, I’ve heard Ella Fitzgerald sing it, I’ve heard Sarah Vaughan sing it, I’ve heard Billie Holiday sing it, I’ve heard Dinah Washington sing it and I’ve heard Tony Bennett sing it. But I have never heard it sung the way Amy sang it. It was and remains beautiful.

There was no doubt that the NYJO and Amy’s other performances pushed her voice further, but it was a friend of Amy’s, Tyler James, who really set the ball rolling for her. Amy and Tyler had met at Sylvia Young’s and they remained best friends to the end of Amy’s life. At Sylvia Young’s, Amy was in the academic year below Tyler, so when they were doing academic work they were in different classes. But on the singing and dancing days they were in the same class, as Amy had been promoted a year, so they rehearsed and did auditions together. They met when their singing teacher, Ray Lamb, asked four students to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ on a tape he was making for his grandma’s birthday. Tyler was knocked out when he heard this little girl singing ‘like some jazz queen’. His voice hadn’t broken and he was singing like a young Michael Jackson. Tyler says he recognized the type of person Amy was as soon as he spotted her nose-ring and heard that she’d pierced it herself, using a piece of ice to numb the pain.

They grew closer after Amy had left Sylvia Young, when Tyler would meet up regularly with her, Juliette and their other girlfriends. Tyler and Amy talked a lot about the downs that most teenagers have. Every Friday night they would speak on the phone and every conversation ended with Amy singing to him or him to her. They were incredibly close, but Tyler and Amy weren’t boyfriend and girlfriend, more like brother and sister; he was one of the few boys Amy ever brought along to my mum’s Friday-night dinners.

After leaving Sylvia Young’s, Tyler had become a soul singer, and while Amy was singing with the NYJO, Tyler was singing in pubs, clubs and bars. He’d started working with a guy named Nick Shymansky, who was with a PR agency called Brilliant!. Tyler was Nick’s first artist, and he was soon hounding Amy for a tape of her singing that he could give to Nick. Eventually Amy gave him a tape of jazz standards she had sung with the NYJO. Tyler was blown away by it, and encouraged her to record a few more tracks before he sent the tape to Nick.

Now Tyler had been talking about Amy to Nick for months, but Nick, who was only a couple of years older than Tyler and used to hearing exaggerated talk about singers, wasn’t expecting anything life-changing. But that, of course, was what he got.

Amy sent her tape to him in a bag covered in stickers of hearts and stars. Initially Nick thought that Amy had just taped someone else’s old record because the voice didn’t sound like that of a sixteen-year-old. But as the production was so poor he soon realized that she couldn’t have done any such thing. (She had in fact recorded it with her music teacher at Sylvia Young’s.) Nick got Amy’s number from Tyler but when he called she wasn’t the slightest bit impressed. He kept calling her, and finally she agreed to meet him when she was due to rehearse in a pub just off Hanger Lane, in west London.

It was nine o’clock on a Sunday morning – Amy could get up early when she really wanted to (at this time she was working at weekends, selling fetish wear at a stall in Camden market, north London). As Nick approached the pub he could hear the sound of a ‘big band’ – not what you expect to hear floating out of a pub at that hour on a Sunday morning. He walked in and was stunned by what he saw: a band of sixty-to-seventy-year-old men and a kid of sixteen or seventeen, with an extraordinary voice. Straight away Nick struck up a rapport with Amy. She was smoking Marlboro Reds, when most kids of her age smoked Lights, which he says told him Amy always had to go one step further than anyone else.

As Nick was talking to her in the pub car park, a car reversed and Amy screamed that it had driven over her foot. Nick was concerned and sympathetic, checking that she was all right. In fact, the car hadn’t driven over Amy’s foot and she had staged the whole thing to find out how he would react. It was the choking game all over again – she never outgrew that sort of thing. I’ve no idea what in Amy’s mind the test was intended to achieve, but after that Amy and Nick really hit it off and he remained a close friend for the rest of her life.

Nick introduced Amy to his boss at Brilliant!, Nick Godwyn, who told her they wanted her to sign a contract. He invited Janis, Amy and me out for dinner, Amy wearing a bobble hat and cargos, with her hair in pigtails. She seemed to take it in her stride, but I could barely sit still.

Nick told us how talented he thought Amy was as a writer, as well as a singer. I knew how good she was as a singer, but it was great hearing an industry professional say it. I’d known she was writing songs, but I’d had no idea if she was any good because I’d never heard any of them. Afterwards, on the way back to Janis’s to drop her and Amy off, I tried to be realistic about the deal – a lot of the time these things come to nothing – and said to Amy, ‘I’d like to hear some of your songs, darling.’

I wasn’t sure she was even listening to me.

‘Okay, Dad.’

I didn’t get to hear any of them though – at least, not yet.

As Amy was only seventeen she was unable to sign a legal contract, so Janis and I agreed to. With Amy, we formed a company to represent her. Amy owned 100 per cent of it, but it was second nature to her to ask us to be involved in her career. As a family, we’d always stuck together. When I’d run my double-glazing business, my stepfather had worked for me, driving round London collecting the customer satisfaction forms we needed to see every day in head office. When he died my mum took over.

By now Amy had a day job. She was learning to write showbiz stories at WENN (World Entertainment News Network), an online media news agency. Juliette had got her the job – her father, Jonathan Ashby, was the company’s founder and one of its owners. It was at WENN that Amy met Chris Taylor, a journalist working there. They started going out and quickly became inseparable. I noticed a change in her as soon as they got together: she had a bounce in her step and was clearly very happy. But it was obvious who was the boss in the relationship – Amy. That’s probably why it didn’t work out. Amy liked strong men and Chris, while a lovely guy, didn’t fall into that category.

The relationship lasted about nine months, it was her first serious relationship, and when it finished, Amy was miserable – but painful though the break-up was, her relationship with Chris had motivated her creatively, and ultimately formed the basis of the lyrics for her first album, Frank.

* * *

Excited as Amy was about her management contract, music-business reality soon intruded: only a few months later Brilliant! closed down. While usually this is a bad sign for an artist, Amy wasn’t lost in the shuffle. Simon Fuller, founder of 19 Management, who managed the Spice Girls among others, bought part of Brilliant!, including Nick Shymansky and Nick Godwyn.

Every year Amy’s birthday cards made me laugh.

As before, with Amy still under eighteen, Janis and I signed the management contract with 19 on Amy’s behalf. To my surprise, 19 were going to pay Amy ?250 a week. Naturally this was recoupable against future earnings but it gave her the opportunity to concentrate on her music without having to worry about money. It was a pretty standard management contract, by which 19 would take 20 per cent of Amy’s earnings. Well, I thought, it looks like she’s going to be bringing out an album – which was great. But, I wondered, who the hell’s going to buy it? I still didn’t know what her own music sounded like. I’d nagged, but she still hadn’t played me anything she’d written. I was beginning to understand that she was reluctant to let me hear anything until it was finished, so I let it go. Amy seemed to be enjoying what she was doing and that was good enough for me.

Along with the management contract, Amy became a regular singer at the Cobden Club in west London, singing jazz standards. Word soon spread about her voice, and before long industry people were dropping in to see her. It was always boiling hot in the Cobden Club, and on one hotter than usual night in August 2002 I’d decided I couldn’t stand it any longer and was about to leave when I saw Annie Lennox walk in to listen to Amy. We started talking and she said, ‘Your daughter’s going to be great, a big star.’

It was thrilling to hear those words from someone as talented as Annie Lennox, and when Amy came down from the stage I waved her over and introduced them to each other. Amy got on very well with Annie and I saw for the first time how natural she was around a big star. It’s as if she’s already fitting in, I thought.

It wasn’t just the crowds at the Cobden Club who were impressed with Amy. After she had signed with 19, Nick Godwyn told Janis and me that there had been a lot of interest in her from publishers, who wanted to handle her song writing, and from record companies, who wanted to handle her singing career. This was standard industry practice, and Nick recommended the deals be made with separate music companies so neither had a monopoly on Amy.

Amy signed the music-publishing deal with EMI, where a very senior A&R, Guy Moot, took responsibility for her. He set her up to work with the producers Commissioner Gordon and Salaam Remi.

On the day that Amy signed her publishing deal, a meeting was arranged with Guy Moot and everyone at EMI. Amy had already missed one meeting – probably because she’d overslept again – so they’d rescheduled. Nick Shymansky called Amy and told her that she must be at the meeting, but she was in a foul mood. He went to pick her up and was furious because, as usual, she wasn’t ready, which meant they’d be late.

‘I’ve had enough of this,’ he told her, and they ended up having a screaming row.

Eventually he got her into the car and drove her into London’s West End. He parked and they got out. They were walking down Charing Cross Road, towards EMI’s offices, when Amy stopped and said, ‘I’m not going to the fucking meeting.’

Nick replied, ‘You’ve already missed one and there’s too much at stake to miss another.’

‘I don’t care about being in a room full of men in suits,’ Amy snapped. The business side of things never interested her.

‘I’m putting you in that dumpster until you say you’re going to the meeting,’ he told her.

Amy started to laugh because she thought Nick wouldn’t do it, but he picked her up, put her in the dumpster and closed the lid. ‘I’m not letting you out until you say you’re coming to the meeting.’

She was banging on the side of the dumpster and shouting her head off. But it was only after she’d agreed to go to the meeting that Nick let her out.

She immediately screamed, ‘KIDNAP! RAPE!’

They were still arguing as they walked into the meeting.

‘Sorry we’re late,’ Nick said.

Then Amy jumped in: ‘Yeah, that’s cos Nick just tried to rape me.’

4 FRANK – GIVING A DAMN (#ulink_39efea69-4596-5a9f-bcf1-5e9bbaa24061)

In the autumn of 2002, EMI flew Amy out to Miami Beach to start working with the producer Salaam Remi. By coincidence, or maybe it was intentional, Tyler James was also in Miami, working on another project; Nick Shymansky made up the trio. They were put up at the fantastic art-deco Raleigh Hotel, where they had a ball for about six weeks. The Raleigh featured in the film The Birdcage, starring Robin Williams, which Amy loved. Although she and Tyler were in the studio all day, they also spent a lot of time sitting on the beach, Amy doing crosswords, and danced the night away at hip-hop clubs.

Because she had gone to the US to record the album, I wasn’t all that involved in Amy’s rehearsals and studio work, but I know she adored Salaam Remi, who co-produced Frank with the equally brilliant Commissioner Gordon. Salaam was already big, having produced a number of tracks for the Fugees, and Amy loved his stuff. His hip-hop and reggae influences can be clearly heard on the album. They soon became good friends and wrote a number of songs together.

In Miami Amy met Ryan Toby, who had starred in Sister Act 2 when he was still a kid and was now in the R&B/hip-hop trio City High. He’d heard of Amy and Tyler through a friend at EMI in Miami and wanted to work with them. He had a beautiful house in the city where Amy and Tyler became regular guests. As well as working on her own songs, Amy was collaborating with Tyler. One night in Ryan’s garden, they wrote the fabulous ‘Best For Me’. The track appears on Tyler’s first album, The Unlikely Lad, where you can hear him and Amy together on vocals. Amy also wrote ‘Long Day’ and ‘Procrastination’ for him and allowed him to change them for his recording.

Amy sent me this Valentine’s Day card from Miami, while recording tracks for Frank in 2003.

By the time Amy had returned from Miami Frank was almost in the can but, oddly, though she’d signed with EMI for publishing nearly a year earlier, she still hadn’t signed with a record label. I kept asking anyone who’d listen to let me hear Amy’s songs, and eventually 19 gave me a sampler of six tracks from Frank.

I put the CD on, not knowing what to expect. Was it going to be jazz? Rap? Or hip-hop? The drum beat started, then Amy’s voice – as if she was in the room with me. To be honest, the first few times I played that CD I couldn’t have told you anything about the music. All I heard was my daughter’s voice, strong and clear and powerful.

I turned to Jane. ‘This is really good – but isn’t it too adult? The kids aren’t going to buy it.’

Jane disagreed.

I rang Amy, and told her how much we’d loved the sampler. ‘Your voice just blew me away,’ I said.

‘Ah, thanks, Dad,’ Amy replied.

Apart from the sampler, though, I still hadn’t heard the songs that were on the short-list for Frank and Amy seemed a bit reticent about letting me listen to them. Maybe she thought lyrics like ‘the only time I hold your hand is to get the angle right’ might shock me or that I’d embarrass her. I teased her after I’d finally heard the song.

‘I want to ask you a question,’ I said. ‘That song “In My Bed” when you sing—’

‘Dad! I don’t want to talk about it!’

Amy came over to Jane’s and my house when she was sorting out the tracks for Frank. She had a load of recordings on CDs and I was flicking through them when she snatched one away from me. ‘You don’t want to listen to that one, Dad,’ she said. ‘It’s about you.’

You’d have thought she’d know better. It was a red rag to a bull and I insisted she played ‘What Is It About Men’. When I heard her sing I immediately understood why she’d thought I wouldn’t want to listen to it:

Understand, once he was a family man

So surely I would never, ever go through it first hand

Emulate all the shit my mother hates

I can’t help but demonstrate my Freudian fate.

I wasn’t upset, but it did make me think that perhaps my leaving Janis had had a more profound effect on Amy than I’d previously thought or Amy had demonstrated. I didn’t need to ask her how she felt now because she’d laid herself bare in that song. All those times I’d seen Amy scribbling in her notebooks, she’d been writing this stuff down. The lyrics were so well observed, pertinent and, frankly, bang on. Amy was one of life’s great observers. She stored her experiences and called upon them when she needed to for a lyric. The opening lines to ‘Take The Box’ –

Your neighbours were screaming,

I don’t have a key for downstairs

So I punched all the buzzers…

– refer to something that had happened when she was a little girl. We were trying to get into my mother’s block but I’d forgotten my key. A terrible row, which we could hear from the street, was going on in one of the other flats. My mother wasn’t answering her buzzer – it turned out that she wasn’t in – so I pressed all of the buzzers hoping someone would open the door.

Of course the song had nothing to do with me buzzing buzzers: it was about her and Chris breaking up. But I was amazed that she could turn something so small that had happened when she was a kid into a brilliant lyric. For all I knew, she’d written it down when it had happened and, eight or ten years later, plucked it out of her notebook. She was a genius at merging ideas that had no obvious connection.

The songs on the record were good – everyone knew it. By 2003, with the record all but done, loads of labels were desperate to sign her. Of all the companies, Nick Godwyn thought Island/Universal was the right one for Amy because they had a reputation for nurturing their artists without putting them under excessive pressure to produce albums in quick succession. Darcus Beese, in A&R at Island, had been excited about Amy for some time, and when he told Nick Gatfield, Island’s head, about her, he too wanted to sign her. They’d heard some tracks, they knew what they were getting into, and they were ready to make Amy a star.

Once the record deal had been done with Island/Universal, suddenly it all sunk in. I sat across from Amy, looking at my daughter, and trying to come to terms with the fact that this girl who’d been singing at every opportunity since she was two, was going to be releasing her own music. ‘Amy, you’re actually going to bring out an album,’ I said. ‘That’s brilliant.’

For once, she seemed genuinely excited. ‘I know, Dad! Great, isn’t it? Don’t tell Nan till Friday. I want to surprise her.’

I promised I wouldn’t, but I couldn’t keep news like this from my mum and phoned her the minute Amy left.

When I think about it now, I realize I took Amy’s talent for granted. At the time I actually thought, Good, looks like she’s going to make a few quid out of this.

Amy’s record company advance on Frank was ?250,000, which seemed like a lot of money. But back then some artists were getting ?1 million advances and being dropped by their label before they’d even brought out a record. So, although it was a fortune to us, it was a relatively small advance. She had also received a ?250,000 advance from EMI for the publishing deal. Amy needed to live on that money until the advances were recouped against royalties from albums sold. Only after that had happened could she be entitled to future royalties. That seemed a long way off: how many records would she need to sell to recoup ?500,000? A lot, I thought. I wanted to make sure that we looked after her money so it didn’t run out too quickly.

When Amy first got the advance she was living with Janis in Whetstone, north London, with Janis’s boyfriend, his two children and Alex. But as soon as Amy’s advances came through she moved into a rented flat in East Finchley, north London, with her friend Juliette.

Amy understood very quickly that if her mum and I didn’t exert some kind of financial control she’d go through that money like there was no tomorrow. I had no problem with her being generous to her friends – for example, she wouldn’t let Juliette pay rent – but she and I knew that I needed to stop her frittering the money away. She was smart enough to understand that she needed help.

Amy and Juliette settled into the flat and enjoyed being grown-up. I would often drop by. I’d left my double-glazing business and had been driving a London black taxi for a couple of years. On my way home from work, I’d go past the end of their road and pop in to say hello, but Amy always insisted I stay, offering to cook me something.

‘Eggs on toast, Dad?’ she’d ask.

I’d always say yes, but her eggs were terrible.

And we’d sing together, Juliette joining in sometimes.

It was around this time that I first suspected Amy was smoking cannabis. I used to go round to the flat and see the remnants of joints in the ashtray. I confronted her, and she admitted it. We had a big row about it and I was very upset.

‘Leave off, Dad,’ she said, and in the end I had to, but I’d always been against any kind of drug-taking and it was devastating to know that Amy was smoking joints.

* * *

As time progressed, everyone at 19, EMI and Universal was so enthusiastic about Frank that I began to believe it was going to sell and that maybe, just maybe, Amy was going to become a big star. On some nights when she had a show, I’d go and stand outside the place where she was playing, like Bush Hall in Uxbridge Road, west London. Her reputation seemed to grow by the minute. I’d listen to what people were saying as they went in, and they seemed excited about seeing her.

Afterwards Amy and I would go out for dinner, to places like Joe Allen’s in Covent Garden, and she would be buzzing, talking to other diners, having a laugh with the waiters. In those days she liked performing live – as a virtual unknown she felt no pressure and simply enjoyed herself; she was always happy after a show, and I loved seeing her like that.

Her voice never failed to blow audiences away, but she needed to work on her stagecraft. Sometimes she’d turn her back on the audience – as though she didn’t want to face them. But when I asked if she enjoyed performing, she’d always say, ‘Dad, I love it,’ so I didn’t ask anything more.

In the months leading up to Frank’s release, Amy did lots of gigs. Playing live meant auditioning a band to perform with her, and 19 introduced her to the bassist Dale Davis, who eventually became her musical director. Dale had already seen Amy singing at the 10 Room in Soho and remembers her flashing eyes – ‘They were so bright’ – but he didn’t know who she was until he went to that audition. Oddly enough, he didn’t get the job at that point, but when her bass-player wanted more money, Dale took over.

Amy and her band played the Notting Hill Carnival in 2003. It’s always a very hard gig – the crowd is demanding – but when I spoke to Dale later, he said that Amy had carried the whole thing on her own. She didn’t need a band. He was knocked out by how great she was, just singing and playing guitar. She might not have been technically the greatest guitarist ‘but no one else could play like Amy and fit the singing and playing together’. Her style was loose, but her rhythm was good and the songs were so strong that it all locked together. As Dale says, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards are not great guitarists: it’s all soul and conviction. ‘You just do it, and throughout the years of doing it you get there.’

Still, Amy’s live performances were not without their struggles. One gig I particularly remember was in Cambridge where she was supporting the pianist Jamie Cullum. Amy and Jamie hit it off and became friends, but when you’re young and just starting out, it’s an unenviable task to be the support act. That night people had come to see Jamie, not her – very few people in the Cambridge audience had even heard of Amy – and initially they weren’t very responsive. But when they heard her sing, they started to get into it. One of the most difficult things about being the support act is knowing when to stop and, as that night showed, Amy didn’t. I don’t blame her because she was inexperienced. Perhaps her management should have clued her up.