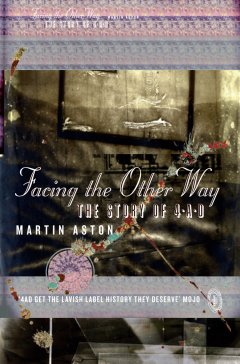

Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD

Àâòîð:Martin Aston

Æàíð: ìóçûêà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:560.42 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 815

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 560.42 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Facing the Other Way: The Story of 4AD

Martin Aston

The first official account of the iconic record label.An NME Book of the Year 2013A Rough Trade Book of the Year 2013A Times Literary Supplement Book of the Year 2013This Mortal Coil, Birthday Party, Bauhaus, Cocteau Twins, Pixies, Throwing Muses, Breeders, Dead Can Dance, Lisa Germano, Kristin Hersh, Belly, Red House Painters.Just a handful of the bands and artists who started out recording for 4AD, a record label founded by Ivo Watts-Russell and Peter Kent in 1979, a label which went on to be one of the most influential of the modern era.Combining the unique tastes of Watts-Russell and the striking design aesthetic of Vaughan Oliver, 4AD records were recognisable by their look as much their sound. In this comprehensive account concentrating on the label’s first two decades (up to the point that Watts-Russell left), music journalist Martin Aston explores the fascinating story with unique access to all the key players and pretty much every artist who released a record on 4AD during that time, and to its notoriously reclusive founder.With a cover designed by Vaughan Oliver this is an essential book for all 4AD fans and anyone who loved the music of that time.

(#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

(#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

Copyright (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by The Friday Project 2013

Copyright © Martin Aston 2013

Martin Aston asserts the moral right to be

identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007489619

Ebook Edition © September 2013 ISBN: 9780007522019

Version: 2015-12-03

(#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

ALSO BY MARTIN ASTON (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

Bj?rkgraphy

Pulp

Acknowledgements (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

In the category of Indispensible, I have to start with Ivo Watts-Russell, for resisting his normal impulse to let the music alone do the talking, and for granting me so much time, commitment and unexpected copy-editing skills. And to Tate, Moke and Emmett, for their part in hosting me. To George, for his part too. Thanks also to Vaughan Oliver, for dedication and contributing extraordinary artwork. To Mat Clum, for his patience and endurance over the course. To the Mieren Neukers of Ladywell, for insight and encouragement. To my HarperCollins editor Scott Pack, for commissioning this book, and project editor Rachel Faulkner, editorial assistant Alice Tarbuck and copy editor Nicky Gyopari, for the finesse. To 4AD, especially Steve Webbon, Rich Walker, Annette Lee, Simon Halliday and Ed Horrox, for assistance/archive. To Madeleine Sheahan, for advice and Spanish translation, and Craig Roseberry, the one and only 4AD Whore – I know what this means to you. And finally, to three 4AD fan websites, Lars Magne Ingebrigtsen’s eyesore.no, Jeff Keibel’s fedge.net and Maximillian Mark Medina’s themysteryparade.com, for comprehensive listings.

Thanks to my two families – in London, Mum, David, Penny, Katie, Vicki and Christopher, Louis, Tess, and in Michigan, Mom Clum, Doug and family, Liz and family, Nate and Bruce, Mindy and Tom.

Many thanks to everyone I interviewed for the book, but especially Miki Berenyi, Mark Cox, Nigel Grierson, Robin Guthrie, Kristin Hersh, Robin Hurley, Matt Johnson, Brendan Perry, Simon Raymonde, Chris Staley and Anka Wolbert. Special thanks to John Grant and John-Mark Lapham, for sound and vision.

Thanks to my nearest-and-dearest: Brenda and Trish, Kurt, Mark, Pixie, Eloise and James, Sara, Will and Harriet, Merle and Gary, Joanna MLNOV, Laura, Yael, Meir and family, Duncan, Amanda, Madeleine, Mary Pat, Gordon, Catherine and Arvo, Nicole, Angela, Hop, Sarah and Foster, Cat my foxymoron, Dr John and Michael, Kat, Peter, Gabby and Trixie, Emma, Jessica and family, Clare and Antoine, Yas, Lauren and Sam, Jesper, Christine and Naomi, David, Yvette and family, Christina, Olivia and Bif, Patrick and Karl, Justin, Lisa and family, Cushla, Felicity, Dean and Britta, the Nervas, the Dutch, Jon and Patricia, Diana and Tim, cousin Jenny, Jim Fouratt, Steve, Mr Stroopy Mumblepants and Spencer, Bob and Jeff, Pat, John, Lynn, Siuin, Debbie, Jude, Sigrid, Amy, Laurence, Miriam and Viva, Jane, Richard, Huw and Dan, Edori and family, Susie and Mark, Lisa, and my Nunhead pals (Karolina, Lukasz, Hugo and Hannah, Claire, Andrew and Eva, John and Katrina, Carolyn, Jeremy and Max).

Thanks also to Tony Bacon, Ralf Henneking, James Nice, LightBrigade PR, Jos? Enrique Plata Manjarr?s and Andy Pearce, and to anyone I have inadvertently missed out, and also not credited for quotes, which I’ve done my upmost to do.

I finally want to thank Tim Carr, one of the insightful people I talked to for this book, and one of 4AD’s greatest supporters, in memoriam.

Dedication (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

This is dedicated to my father Basil, in memoriam, and to my mother Patricia. Thanks for not insisting I pursue a career in merchant banking.

To Moray, in memoriam. I hope you are grooving in your home disco, reading, writing and meditating, looking forward to tralaalaa o’clock.

Epigraph (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

Imagine a scene on a beach. A barbecue for friends and colleagues. Some of them like each other and some of them don’t. The man in charge, responsible for inviting them all, and responsible for feeding them, suddenly self-combusts. In his confused, mad dash to reach the water, to put out the flames, he ricochets into those closest to him and knocks them down, even starting minor fires over their bodies. Before he reaches the ocean, he passes through a pile of fireworks lying on the beach for use in a display later that night. All hell breaks loose, with everyone on the beach scattering, trying to save themselves. The man has now reached the water and finds he has gone out too far and has forgotten how to swim. He is drowning but unable to call for help. He is totally aware of the chaos on the beach that he is responsible for and has left behind but, because he’s drowning, can do nothing to prevent the destruction. He is puzzled as to why no one is coming to his rescue. Meanwhile, everyone to a man back on the beach is thinking, ‘You stupid cunt. What did you do that for, you’ve ruined everything’ and ‘For fuck’s sake, just swim’.

(George, 2013)

Contents

Cover (#uc87fe1e7-f944-54d1-94d9-f3681a66d6ae)

Title Page (#ulink_016cd898-bcfd-589a-8adf-70e894d302c4)

Copyright (#ulink_ffb534d2-d213-5de5-9e02-3839ef6bdcec)

Also by Martin Aston (#ulink_8a20cebf-141c-5215-b2b6-c71ca1539e5f)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_f2fe626f-4a71-5992-8f1d-0fe10dc4b596)

Dedication (#ulink_0e216507-bf6d-5710-b69e-2c16a2a6f2d9)

Epigraph (#ulink_7c7ca4ff-32d2-5d26-a381-63139fd1262b)

Introduction (#ulink_756fd1ee-cf2b-52d7-9843-2ea1255e6281)

1 Did I Dream You Dreamed About Me? (#ulink_71fe4f1f-7b06-5860-8e9b-f97649541087)

2 Piper at the Gates of Oundle (#ulink_2095c489-bf64-5720-9840-5a49d862dfa8)

3 1980 Forward (#ulink_df37f2a0-79fb-56f3-b2ed-4fbab3caaf12)

4 Art of Darkness (#ulink_6f03723e-36f7-56e2-bb29-c80f2799d054)

5 The Other Otherness (#ulink_70f65a22-171b-5efb-a493-8db20d23edb8)

6 The Family That Plays Together (#ulink_42b42d6b-d24a-510d-ba8c-7ec31f92c99c)

7 Dreams Made Flesh, but It’ll End in Tears (#ulink_e09f3e8b-bcdc-5d20-93d3-c67fb775ea50)

8 The Art Shit Tour and Other Stories (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Le Myst?re des Delicate Cutters (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Chains Changed (#litres_trial_promo)

11 To Suggest is to Create; to Describe is to Destroy (#litres_trial_promo)

12 With Your Feet in the Air and Your Head on the Ground (#litres_trial_promo)

13 An Ultra Vivid Beautiful Noise (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Heaven, Las Vegas and Bust (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Fool the World (#litres_trial_promo)

16 A Tiny Little Speck in a Brobdingnag World (#litres_trial_promo)

17 America Dreaming, on Such a Winter’s Day (#litres_trial_promo)

18 All Virgos are Mad, Some More than Others (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Fuck You Tiger, We’re Goin’ South (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway (#litres_trial_promo)

21 As Close as Two Coats of Paint on a Windswept Wall (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Smile’s OK, a Last Gasp (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Everything Must Go (#litres_trial_promo)

24 Full of Dust and Guitars (#litres_trial_promo)

25 Facing the Other Way (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustrations Insert (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

When a fan of 4AD, and of the British independent label scene of the Eighties in general, heard I was writing this book, he asked me, ‘Is there much drama in the 4AD story?’

True, the story of 4AD doesn’t feature a TV presenter-cum-entrepreneur who starts a record label whose most iconic frontman commits suicide and initiates a Che Guevara-style cult; nor does it involve the decision to invest heavily in a nightclub that goes on to become an epicentre of the biggest dance music boom in UK history, rejuvenating both youth and drug culture, the combined legacy of which soon enough bankrupts said label.

That would be the suspenseful saga of Manchester’s Factory Records, 4AD’s principal peer in the world of pioneering, inventive and maverick independent labels. For both labels, the visual aesthetic was as crucial as the music, yet, in many ways, south London’s 4AD, formed in 1980, was the anti-Factory: its spearhead, Ivo Watts-Russell, was more of a recluse than a media-savvy self-promoter, and 4AD had no recognisable ties to the zeitgeist – nor to any cultural trend, in fact. All of that, Ivo felt, was irrelevant; only the artefact mattered – the music and its exquisite packaging. In the mid-Eighties there were constant references to ‘the 4AD sound’: a beautiful, dark, insular style. If the 2002 fictionalised film about Factory Records was called 24 Hour Party People, what might a film about 4AD be titled – Eight Hours Chilling, and Then Bed?

But whilst 4AD’s story may be less sensational and populist than Factory’s, it is equally gripping, the label’s A&R vision being that much greater, and its subsequent cast of characters even more fascinating and beguiling. Under Ivo, 4AD’s vision chimed with a rare era in British pop history when there was a sizeable market for innovation and experimentation. The artists he was drawn to were trailblazers, outsiders whose unique perspective invariably included a troubled, sometimes irreconcilable relationship with the mainstream (scoring the UK’s first independently released number 1 single was as much the beginning of the end for 4AD as it was the start of a new era), and with each other, like a dysfunctional family – and that includes the staff at the record label.

Like the motion of the swan’s legs beneath its ineffably elegant glide across water, below the surface of 4AD’s dazzling and enigmatic artwork and music the human drama unfolded. 4AD’s journey began as a shared discovery of a new world of sound and opportunity in the aftermath of the punk rock revolution. But its community was progressively fractured by splits, rivalries, writs, personal meltdowns, addiction, and depression – not least of the victims being 4AD’s most iconic artists Cocteau Twins, Pixies and The Breeders, and the label boss as well.

Though 4AD became increasingly popular in the first half of the Nineties, the shifts in the cultural climate and music business practise, as the major labels and the mainstream sought to exploit ‘alternative music’, was enough to shatter Ivo’s dream to the point that he sold up in 1999 and disappeared into the New Mexico desert, cutting all ties to the music industry.

Also unlike Factory, 4AD has survived – some even claim that in the twenty-first century, the label, under new stewardship, has reclaimed its former glory. However, it is the Eighties and Nineties, the years under Ivo’s tutelage, that are the real story. This is the period that Facing the Other Way concentrates on: a time in which the word ‘4AD’ became an adjective, when 4AD was the most fanatically appreciated and collected of record labels, whose legacy casts a long shadow over contemporary music, from dream-pop, goth, post-rock and industrial to Americana, ambient, nu-gaze and chillwave. Not forgetting Pixies’ indelible influence on Nirvana, whose impact pushed alternative rock into the mainstream, after which there was no return.

There was no return for Ivo either. His non-existent profile since the end of the twentieth century means that one of the great sagas of British-label history had not been told. That is, until I went looking for him in 2010.

I’d been a 4AD fan throughout the earlier years, from Bauhaus’ early singles to The Birthday Party and Cocteau Twins, and as soon as I started writing about music, in 1983, I’d had a close working relationship with Ivo. Over the years, I’ve covered numerous 4AD artists, and been beguiled and exhilarated by the procession of sounds and names: Dif Juz, This Mortal Coil, Dead Can Dance, Throwing Muses, Pixies, The Wolfgang Press, His Name Is Alive, Lush, Red House Painters, Tarnation … But, in the wake of Ivo’s retreat, our last correspondance was in 2002 (regarding some sleevenotes I was writing about one of Ivo’s favourite 4AD signings). Arguably, a book on 4AD could have been written then, but it makes more sense now, with the label’s reputation, and myth, increasing year on year. This is a testament to a label that existed purely on its own terms, out of time and place with the rest. Facing the other way. Sometimes it’s the quiet ones you have to look out for …

chapter 1

Did I Dream You Dreamed About Me? (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

Creativity is a product of a diseased mind.

(Dee Rutkowski, 2011)

I have the strangest dreams every night … been going on for months. Unlike my waking life, the dreams are full of strangers that I am forced to interact with. I’m not sure whether I experience greater feelings of alienation asleep or awake.

(Ivo, by email, 2012)

Yes: I am a dreamer. For a dreamer is one who can only find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he sees the dawn before the rest of the world.

(Oscar Wilde, sometime in the late nineteenth century)

May 1985. The phone rings at Ivo’s home on a Saturday afternoon. ‘It’s David Lynch’s assistant: are you free to talk to him?’

The American film director behind the startling, surreal Eraserhead and the dramatically different, but equally affecting, biopic The Elephant Man had a new film in pre-production, titled Blue Velvet, and he’d fallen for a song that he wanted to use for the opening sequence, set at a high-school prom.

The song was a cover of Tim Buckley’s ‘Song To The Siren’, a mercurial, exquisite ballad that described, in aching and elaborate homage to the ancient Greek poet Homer’s epic The Odyssey, the inevitable damage that love causes. Buckley’s original, which the Californian singer-songwriter had written and first recorded in 1968, wasn’t at all well known, even by 1985. Between 1966 and 1974, he’d recorded a startling array of music over the course of nine albums, from folk rock to jazz to avant-garde to funky soul and AOR. It all ended with a snort of heroin at an end-of-tour party. With rock and pop culture yet to turn nostalgic, Buckley’s reputation had died with him, and punk rock’s Stalinist purge of the past had ensured that Californian singer-songwriters of all pedigrees were discourteously dismissed.

But this new cover version of ‘Song To The Siren’, by a studio-based collective named This Mortal Coil, had sprung up in a very different climate. Punk had given way to its more experimental, artful offspring, post-punk, alongside the new electronic sound, and the synthesised pop called New Romantic. ‘Song To The Siren’ had spent more than a hundred weeks in the British independent music charts during 1983 and 1984, and its fame had reached America, as David Lynch’s interest illustrated. He regards TMC’s version as his all-time favourite piece of music: ‘That song does something to me, for sure,’ he told the Guardian newspaper in 2010.

In either version, ‘Song To The Siren’ was an easy track to be infatuated with, given its sorrowful, elegiac mood, and its lyrics haunted by images of the sea and of death. The singer of This Mortal Coil’s version was Elizabeth Fraser, whose performance – supported in spirit by the guitar of her musical and romantic partner Robin Guthrie – suggested that she was the siren of The Odyssey personified, luring sailors/lovers to a watery grave.

In their daily lives, Fraser and Guthrie were known as Cocteau Twins, recording artists for the independent music label 4AD. It was 4AD’s co-founder, and singular leader, Ivo Watts-Russell, that had taken Lynch’s call that afternoon. ‘As happens,’ Ivo recalls, ‘when the film went into production, my friend Patty worked as an assistant to the producer on Blue Velvet. She’d call me, whispering, “David and Isabella [Rossellini, the female lead] are in the corner again, listening to ‘Song To The Siren’,” before shooting a scene.’

The cover version, recorded in 1983, had been Ivo’s idea. The late Tim Buckley is his all-time favourite singer, and ‘Song To The Siren’ is still his all-time favourite song. ‘Not since Billie Holiday had recorded “Strange Fruit” was a song and lyric so suited to a voice as Tim Buckley’s was to “Song To The Siren”,’ he reckons.

By 1985, the inimitable Elizabeth Fraser had become his favourite living singer. And here was Lynch, requesting not just the music for Blue Velvet but Fraser and Guthrie to mime on stage in the prom scene. However, the lawyers for Buckley’s estate demanded $20,000 for the rights, scuppering Lynch’s plans (the film’s total budget was only $3 million). The director quickly turned to composer Angelo Badalamenti, who attempted to mirror the track’s displaced, eerie mood with a new song, ‘Mysteries Of Love’, sung by the American singer Julee Cruise with her own take on haunting, ethereal projection. Starting with Blue Velvet, and most famously on his TV series Twin Peaks, Lynch fashioned a world that appeared seamless, unruffled and presentable on the surface, but scarred and disturbed underneath, foaming with a barely controllable darkness. As Twin Peaks’ FBI Special Agent Cooper declared, ‘I’m seeing something that was always hidden.’

In 2006, Ivo pointed to a similarity between label and director. ‘I feel that 4AD is like David Lynch,’ he told the Santa Fe Reporter. ‘If you say to somebody, “It’s kind of like a David Lynch movie”, you kind of know what you’re getting. It was like that in the same way for a certain period at 4AD: “It’s kind of like a 4AD record”. Actually, that probably meant it had loads of reverb.’

By this, Ivo wasn’t referring to something hidden – more that it was a brand that could be identified, where the term 4AD had become an adjective of sound. Yet in the music that the label was producing, there was the same sense of beauty as a mask for the true emotions coursing beneath. By 1985, the so-called ‘classic’ 4AD sound was all about dark dreams and hidden depths, performed by supposed fragile characters on the verge of anguish and breakdown. Take Elizabeth Fraser. After the drooling reception for her performance in ‘Song To The Siren’, she didn’t grow in confidence, but began to sing in what resembled a made-up language, or simply by enunciation, making it impossible to be understood. With a voice like hers, she didn’t need words; it was all there in her delivery, a shiver of emotion from agony to ecstasy.

March 2012. It’s been thirteen years since Ivo stood down from running 4AD and sold his 50 per cent share of the label back to his business partner Martin Mills, the head of the Beggars Banquet group of companies. But his legacy clearly lives on. The weekend edition of the Guardian has just published a feature on 4AD. ‘What is it about a record label that makes it the sort of place you want to spend time in?’ asks writer Richard Vine. ‘When it first emerged in the 1980s, 4AD felt like one of the most enigmatic worlds, the sort of label that you wanted to collect, that brought a sense of “brand loyalty” way before it occurred to anyone to talk about music in such crass terms.’

Vine cites Ivo as the reason, adding, ‘But arguably just as important to the label’s cohesion was designer Vaughan Oliver and photographer Nigel Grierson whose covers gave 4AD its distinct, haunted, painterly quality. It felt like you were peeking into a carnival full of beautiful freaks who didn’t want to be seen.’

So much of the music released on 4AD during Ivo’s era had this same creative tension, beauty masking secrets, feelings buried, persisting in anxious dreams and suppressed fear, hope and anger; lyrics that don’t explain emotion as much as cloud the issue, penned by a carnival full of beautiful freaks who didn’t want to be seen. Isn’t that what music does best, express feelings that words can’t articulate? Emotion that can’t be attached to a view or opinion, to a time or a place, is often the most timeless and precious.

People have long attached an obsessive importance to 4AD, and cited its enduring influence. On its own, This Mortal Coil’s ‘Song To The Siren’ drew extravagant praise. At the time, vocalists Annie Lennox (Eurythmics) and Simon Le Bon (Duran Duran) voted it their favourite single of the year. Today, Antony Hegarty (Antony and the Johnsons) calls it, ‘the best recording of the Eighties’. The song was to make an indelible impression. ‘For years, I was spellbound by the Julee Cruise catalogue but I didn’t know why,’ says Hegarty. ‘It was so beautiful and yet so horribly cryptic; there seemed to be something terrible lurking beneath the breathy sheen. Years later, I understood when I discovered that Lynch had originally wanted to license “Song To The Siren”.’

Irish singer Sinead O’Connor was just seventeen when her mother was killed in a car crash. ‘It was the record that got me through her death. In a country like Ireland where there was no such thing as therapy, self-expression or emotion, music was the only place you had to put anything. I played “Song To The Siren” nearly all day, every day, lying on the floor curled up in a ball, just bawling. I couldn’t understand the words much, but [Fraser’s] way of singing was the feeling I didn’t how to make. I still can’t move a muscle when I hear her sing it.’

July 2012. Ivo is driving from his New Mexico home in Lamy towards Santa Fe to an appointment with a new therapist, with Emmett sitting pillion; his black Newfoundland-Chow mix is the most eager of Ivo’s three dogs to go along for the ride, and Ivo loves his company anyway. Clouded memories of former sessions, in the inevitably elusive pursuit of happiness and to understand the nature of depression, persist as he passes through the jagged, barren landscape, the sun playing shadow games on the mounds of burrograss, the rust-coloured earth framed 360 degrees by the mountains. So much beauty and light. But inside his head, sadness and darkness.

On arrival, Ivo is pleasantly surprised when the therapist agrees Emmett can stay. ‘That’s the way to do therapy,’ Ivo reckons. ‘And Emmett loves our time together.’ But Ivo is not here to discuss Emmett, except in relation to how dogs have taught him to love unconditionally. ‘Something I have struggled to do with people,’ he says.

The black dog at his feet during the session has a special significance for Ivo. Depression is often known as ‘the black dog’, as British politician Winston Churchill famously labelled it. In 1974, towards the end of his young life, the British folk singer Nick Drake wrote ‘Black-Eyed Dog’ about the same subject. ‘A black-eyed dog he called at my door/ A black-eyed dog he called for more/ A black-eyed dog he knew my name …’

Andrew Solomon’s book The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression summarised such depression: ‘You lose the ability to trust anyone, to be touched, to grieve. Eventually, you are simply absent from yourself.’

‘Try running a record company with two offices and over a dozen members of staff with countless artists looking to you for advice, guidance and financial support in that condition,’ says Ivo.

Up in the high desert of New Mexico, 7,000 feet above sea level and 18 miles outside of the state capital Santa Fe, the community of Lamy is comfortably off the beaten track. It was once a vital railroad junction: the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) line – colloquially known as the ‘Santa Fe’ – was to stop in Santa Fe but the surrounding hills meant that Lamy was a more practical destination. But few people disembark here now. The restaurant (in what was the plush El Ortiz hotel) and tiny museum are outnumbered by the rusting, abandoned rail carts, memories of a more prestigious past. Not many people live here either: the 2010 census gave a population count of 218.

By nightfall, a hush descends; it’s the kind of place where you come to get away, or hide away, from it all. To give an idea of its isolation, America’s first atomic bomb was tested just two hours away. It’s a landscape on to which you can put your own impression, and also disappear into. ‘I’ve moved to where I feel my most comfortable,’ Ivo confesses. ‘But people just think I’m eccentric.’

It’s here, on a ridge outside of Lamy, that Ivo built his house. On the roof, you can see 360 degrees to the surrounding mountains. To the left, the Manzanos; straight ahead towards Albuquerque, the Sandias; to the right above Los Alamos, the Jemez and the Sangre de Cristo ranges that host ski season. Trails lead through the rock and scrub, but generally only dog walkers follow them; the remoteness is both impressive and comforting. In his decidedly modernist house, which stands out among New Mexico’s predominantly pueblo architecture, Ivo lives with his three dogs, his art, his music and his privacy. It’s an idyll, a hideaway, a fortress, possibly even a prison. Sometimes the only sounds are the sighs, whines and occasional barks of his dogs. The sun bakes down for much of the year. The skies are huge, the silence deafening.

Among the albums is a box set of This Mortal Coil recordings that Ivo recorded back in the day with a revolving cast of musicians, some close friends and others mere acquaintances. Some remain friends; others he hasn’t seen, talked or corresponded with for many years. No expense was spared in the mastering of this music or the packaging of the collectors CD format known as ‘Japanese paper sleeve’, though the high-end quality is more like stiff card, like it’s a book or a piece of art. These miniature reproductions of the original vinyl album artwork, only reproduced by specialist manufacturers in Japan, is the antithesis of the intangible digital MP3 that now defines music consumption. ‘I’m fascinated by the quality of what the Japanese do, and the obscurity of some of the releases they archive and document,’ Ivo says. ‘Record companies say that no one buys finished product anymore. So why not give them something of beauty?’

Shelves and drawers in Ivo’s rooms contain thousands of these limited edition box sets, which he trades as a hobby, to turn a profit if he can, ordering early and then selling on once they have sold out. After a period of not even being able to listen to music, it has again become an obsession. The music industry, or rather 4AD’s place in it, used to be an obsession as well. Not anymore. Now it’s a foggy, jumbled-up memory of highs and lows, a black dog growling at the foot of his mind.

Much contemporary music has a similar effect. Edgy, glitchy electronic music, the currency of the present technological age, ‘is just wrong for my brain,’ Ivo shrugs. He also admits he very rarely sees any live music anymore; too many people, too much fuss. The concept of the latest sound, the latest trend, the hyped-up sensation, leaves him cold. It has to be music that exists for its own sake. Music that can provide what he describes as ‘solace and sense’. For the most part, Ivo explains, ‘it doesn’t involve the intellect, but evokes an emotional response. It draws one away from analysis, from the brain constantly questioning.’

This music often comes from his past, discovered in his youth or while he was building 4AD’s catalogue, when he experienced epiphanies, love affairs, drug trips, through a cassette demo or a live show, before there was even the awareness of a black dog or what it meant to run a business. Music from the worlds of American folk and country appear to provide the most solace and sense these days. But the uncanny world of progressive rock rooted in the Sixties and Seventies, fusing the techniques of classical and avant-garde music to play havoc with tempo, texture and access, has become a recent fascination. ‘Give me originality,’ he says. ‘Give me something challenging. I listen to music now and I’m always running an inventory in my head of what it reminds me of. I mean, if you’re going to copy, to mimic, without putting an ounce of yourself into it …’

Ivo hasn’t recorded any of his own music since 1997, when he assembled a series of cover versions under the name The Hope Blister. ‘There have been a couple of times where I’ve talked about it,’ he admits. ‘I sent tapes out for people to consider, but I couldn’t go through with it. In any case, I haven’t had an original idea for years. In fact, I have no idea how I was ever that imaginative.’

Yet despite his disappearance into the desert and retirement, Ivo’s opinion clearly still stands for something. Colleen Maloney, 4AD’s head of press through the Nineties and currently at fellow south London independent Domino, heard that Ivo had fallen for Diamond Mine, a collaborative album between Scottish vocalist King Creosote and British electronic specialist Jon Hopkins that Domino had released in 2011. Ivo’s name subsequently appeared on a press advertisement beside the quote: ‘the best vocal record of the last twenty years’.

‘It’s so full of atmosphere, so sharp and so sad,’ he says, nailing the very qualities that so often elevated the music released on 4AD to such sublime heights. But, as the clich? goes, the higher you climb, the harder you can fall. Beneath the beauty, lies a deeper ocean of emotion in which to drown.

chapter 2 – 1980 (1)

Piper at the Gates of Oundle (#u07d22796-56d0-5413-918d-fa0dabf912b5)

(BAD5–BAD19)

Far from Lamy, the ancient market town of Oundle in the UK has a markedly different flora, fauna and geography – flatter, greener, though just as sedate. In a rural idyll 70 miles north of London in the county of Northamptonshire, Oundle is also isolated: 12 miles from the nearest main town of Peterborough, and almost surrounded on three sides by the River Nene.

The house where Ivo grew up was also isolated – the driveway to the main house was half a mile long. The Watts-Russells are inextricably linked to Oundle: records show that Ivo’s ancestor Jesse Watts-Russell Junior built the town hall and the church, though it’s the ancient church in the nearby village of Lower Benefield that can be seen through the avenue of trees from the estate’s manor house.

Ivo’s family came from aristocratic money, but while they still own much of the land in the area, the low-rent tithes set by his grandmother in the 1930s drastically reduced the income. The farmhouse property where Ivo was raised while his grandmother occupied the manor house had broken windows in every room. ‘Sixty years earlier, the family name was a presence – my grandparents’ marriage was society news,’ he recalls. ‘But the reality was five of us in one bedroom, and the farm itself was only a modest success.’

Ivo’s father served in the British army in Egypt before and during the Second World War, and in Germany afterwards, before returning to Oundle in 1950 to run the estate farm. Ivo was born four years later, named after Ivo Grenfell, a cousin on his grandmother’s side and brother of the First World War poet Julian Grenfell, whose famous war poem ‘Into Battle’ was published the same month he was killed in 1915. Ivo was the youngest of eight, with two brothers and five sisters. By the time his grandmother had died in 1969 and Ivo’s family moved into the manor house, all his siblings had left home. His other brother Peregrine (known as Perry) remembers Ivo assisting with the move in a rare bonding exercise with an emotionally distant father.

‘My older sister would joke, though not necessarily so, that the first time our dad talked to us was when we’d each turned fifteen, and he’d say, “OK, get on the tractor and drive”. He was a very aloof man, who lost his own father when he was seven and was raised by a tyrannical Victorian English mother. We never related emotionally to either parent.’

Ivo’s mother was diagnosed with tuberculosis when he was born in 1954, keeping her and the baby apart for three months for fear of passing on the potentially fatal disease. It was a harsh domestic regime of a father with a farm to run and a mother raising eight children without modern appliances … ‘I don’t remember many visitors,’ says Ivo. ‘My uncles would come for the weekend, and then we’d have fun.’

In any environment of emotional deprivation, any form of art can become a vital lifeline, a source of comfort, inspiration and imagination. Ivo’s pre-teen memories were of the rousing film soundtracks to South Pacific and The Sound of Music. Even earlier, West Side Story, the first ‘teen’ musical, was his introduction to the culture of attitude, fashion and sex (‘Got a rocket in your pocket, keep coolly cool, boy!’). All three musicals emphasised the urge to escape, from ‘Climb Every Mountain’ and ‘Over The Rainbow’ to the lovers Tony and Maria from West Side Story believing, ‘there is a place somewhere’ – a better place, beyond the control of authority and circumstances.

Eight children meant pop music was always in the Watts-Russell house. For Perry, it was The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. ‘There was a three-year age gap between me and Ivo,’ he says, ‘so they couldn’t be his soundtrack to adolescence.’ Ivo has no memory of why the first single he bought at the age of six was ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’ by R&B legend Ray Charles. EPs by The Who and The Kinks followed, but his epiphany, the road from Oundle to Damascus, was The Jimi Hendrix Experience miming to the trio’s debut single ‘Hey Joe’ on a 1967 edition of BBC TV’s weekly flagship music show Top of the Pops. Their Afro hairstyles alone would have triggered intrigue in middle England, even consternation. But it was Hendrix’s sound – liquid, sensual, aching, unsettling, alien – that had coloured the imagination of an impressionable twelve-year-old, thrilled at the subversive invasion of a drab farmhouse lounge.

‘My sister Tessa and my parents were watching too and I remember a shared feeling of jaws dropping, of confusion,’ Ivo recalls. ‘I thought, this is having an impression, and being very interested by that. The next Saturday, I listened to [BBC radio DJ] John Peel’s Top Gear, with sessions by Cream, Hendrix and Pink Floyd. I bought Hendrix’s Are You Experienced and Pink Floyd’s equally mind-altering Piper At The Gates Of Dawn. I’d finally found, to paraphrase John Lennon, the first thing that made any sense to me. My gang.’

These weren’t the cool Sharks or Jets gangs of West Side Story, but the freaks, in all their animalistic glory. In this first flowering of psychedelia, the possibilities were endless. ‘How mad was [Pink Floyd’s] “Apples And Oranges” as a single?’ says Ivo. ‘What a brilliant reflection of the times. Aurally and visually, this was the counter-culture, the hope for the future.’

Despite his advanced tastes, Ivo – or George as he was affectionately known – wasn’t allowed to join Perry and his friends at a concert with the epic bill of American R&B singer Geno Washington and the kaleidoscopic heaviness of Pink Floyd, Cream and The Jimi Hendrix Experience. His first ever show was more pop-centric but still staggering – The Who, Traffic, Marmalade and The Herd. ‘Ivo was much more obsessive about music than I was,’ Perry recalls. ‘He wasn’t yet distracted by girls, so music was the means by which you formed an identity. It spoke to him in ways that regular life didn’t. He’d listen to Peel religiously, while I was so taken up with school.’

While his older brother studied intensely to pass his Oxbridge entrance exams, Ivo wasn’t academic (or sporty), and music played an even more defining role. ‘I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere,’ he says. ‘I couldn’t relate to anything I was being taught.’

His first chance to physically escape came that summer of 1968. Aged fourteen, Ivo and a school friend plotted to follow their friend Peter Thompson, one year older, to London. Thompson was squatting in a dilapidated house in the city centre near Marble Arch, helping to distribute Richard Branson’s first venture, the free magazine Student. It was in this house, which doubled as Student’s HQ and Branson’s living space, that Ivo smoked hash for the first time. But his education in this new illicit high was short-lived after an errant joint smoked by another schoolboy implicated Ivo.

His subsequent expulsion from school alongside two other boys made the news in Peterborough. ‘Our family’s position in society in that part of rural England stretched back two hundred years,’ says Perry. ‘It was a traumatic, life-affecting experience for Ivo and he was treated as a pariah. Maybe it drove him towards music being even more of a saviour.’

The cloud’s silver lining turned out to be the offer of a place at a nearby technical college where the class system, peer pressure and school uniforms didn’t apply, and girls were everywhere. Ivo persisted with buying records with odd-job cash, guided by John Peel’s tastes; his next pivotal discovery was the Los Angeles quartet Spirit, led by prodigious teenager Randy California, a peer and friend of Jimi Hendrix who specialised in an ‘infinite sustain’ guitar technique, by aligning guitar feedback with the note that creates it. Ivo recommends the delicately searing solo in ‘Uncle Jack’ from 1968’s debut album Spirit: ‘I still get the same tingling feeling as when I first heard it.’

The doors of perception swung open to the sound of The Nice’s keyboard-heavy The Thoughts Of Emerlist Davjack and Deep Purple’s proto-heavy Shades Of Deep Purple, and especially The Mothers of Invention’s heavy satire We’re Only In It For The Money, which Ivo found more intriguing and challenging than Hendrix. For starters, chief Mother Frank Zappa mocked not only the establishment’s corporatisation of youth culture but the hippie dream too, hard to take for dreamers such as Ivo. Zappa claimed both sides were ‘prisoners of the same narrow-minded, superficial phoniness’.

More crucially, the album was assembled like a collage, an anarchic and operatic meld of jazz, classical and rock that consistently changed tack. ‘All these noises and whispers, the chop-ups and talking … It proved to be incredibly influential on me, how something that cropped up in one song reappeared in another seven tracks later,’ Ivo recalls. ‘It made me think about how an album could be assembled. And if that kind of record can become normal, it suggests one is really open to pretty much anything in music. And that was me set. I had this ongoing relationship with whatever was contained within a twelve-inch-square sleeve. That’s what I lived for.’

Ivo soon got to see The Mothers of Invention on stage. Other formative concert experiences were psychedelic seers King Crimson and Pink Floyd. To Ivo, Syd Barrett was the personification of cool, and even once Barrett’s fragile eggshell mind had broken, like the acid Humpty Dumpty, he believed fully in Floyd’s subsequent journey to the outer reaches of space rock. The realisation that music could be a journey sent Ivo on his own quest to unearth music of an equivalent mindset.

A recommendation to investigate the burgeoning acid rock scene over on America’s west coast introduced Ivo to traditional folk/country roots, through Buffalo Springfield’s newly liberated frontman Neil Young and the collective jamming of The Grateful Dead. ‘I was exposed to more than the electric guitar individuality that English bands had,’ he recalls. And it wasn’t long till Ivo was exposed to acid itself, experiencing his first hallucination in Kettering’s Wimpy hamburger bar in the company of his friend (and future heavy metal producer) Max Norman. Ivo’s parents allowed Max’s band to rehearse in a cottage on the family estate; Ivo acted like their roadie: ‘I’d bash away at the drums, but I never dreamt of picking up a guitar or learning an instrument. I was the only one of the eight kids to not have piano lessons, though musically none of us were remotely gifted.’

In 1972, when they were eighteen, Max and Ivo hatched a plan to move to London, which failed after one day when the friend they hoped to stay with turned them away. A month later, Ivo returned alone. Drawn to High Street Kensington because of its popular hippie market, he spotted a shop on Kensington Church Street called Norman’s with Floyd’s Piper At The Gates Of Dawn (already five years old) in the window. It was run by a father and daughter partnership. ‘The place was shabby and out of time but it still appealed to me, so I asked if they had a job going. By the time I’d got home, the father had called, saying I could help on the record side. I think his plan was to train me to run the shop with his daughter.’

Ivo and two college friends subsequently moved into a basement flat in nearby Earls Court, stricken by damp and frogs in the kitchen, but there’s no place like home. ‘Behind the counter, that was my territory,’ Ivo says, ‘just as behind my desk at 4AD later on. But I was still incredibly shy.’

Six months later, Ivo had had enough of Norman’s. ‘The stock was limited and we’d get asked for a Steely Dan album but we didn’t have a clue because it was only on import. It was a road to nowhere.’ In an early and risky show of self-determination, he left Norman’s and moved in with his sister Tessa’s boyfriend in the nondescript outer west London suburb of Hanwell. One day, exploring the busier streets of nearby Ealing, he found a branch of Musicland, a more clued-in record retailer. After boosting his credibility by asking for the album Alone Together by [Traffic’s] Dave Mason, he asked the manager, Mike Smith, for a job. Smith happened to need an assistant, but he accurately predicted Ivo would be managing his own Musicland branch within two months.

Ivo ran Musicland in the deeply dull suburb of Hounslow – had the Sixties even reached Hounslow, let alone the Seventies? – but he managed to return to Ealing when Musicland – now called Cloud Seven after a takeover – transferred Mike Smith to another branch. It was now 1972, the time of glam rock, a revolution in dazzling sound and satin jackets, which helped British pop escape the cul-de-sac of denim and hard rock, a world of singles as well as albums. But Ealing, with its copious clubs, bars and students, had held on to its Sixties dream, as one of London’s musical epicentres, the birthplace of British jazz and blues where The Rolling Stones had got their first break.

One regular at the Cloud Seven shop was Steve Webbon. A few years older than Ivo, Webbon had boosted his credibility by quizzing Ivo about country rock pioneer Gram Parsons – and then asking about a job. Ivo hadn’t heard of Parsons, but he’d found his assistant.

Steve Webbon currently runs the back catalogue department of both 4AD and Beggars Banquet labels. In the late Sixties, he studied at Ealing Art School, moving on to unemployment benefit and spending most of it in Cloud Seven, in thrall to the sound of west coast American music. Manned by its two Yankophiles, Cloud Seven stocked up on what Gram Parsons had labelled ‘cosmic American music’, before he died, like Tim Buckley, of a heroin overdose. Nowadays, people call it Americana, a repository of roots music that pined for a simpler, humanistic society while rejecting the flash and excess of rock’n’roll. Only in the shape of Bob Dylan and The Band’s return to American roots did British audiences pay attention; in America as well as the UK, Parsons’ raw, Nashville-indebted sound was overshadowed by the softer, sweeter bedsitter folk of the era’s million-selling singer-songwriters such as Carole King and James Taylor.

Next to this, Ivo felt glam rock and its more adult cousin art rock to be inauthentic. ‘It was too “look at me”, too frivolous. I later learnt that there was depth there, and obviously there was something different about David Bowie. But his Ziggy Stardust explosion had put me off, and Alice Cooper and Roxy Music weren’t serious enough either.’

Ivo was happy in his domain behind the Cloud Seven counter: ‘I was having a whale of a time. Until I got mugged, that is.’ It was just before Christmas 1973; the victim of a second mugging that evening died from the attack. Carrying the night safe wallet after shutting up the shop, Ivo was knocked unconscious, landing face first and breaking his nose: ‘I was freaked out, and left London, back home to Oundle, to the womb. But I immediately knew I’d made a stupid mistake.’

After two months, Ivo called Cloud Seven and got a desk job at the company head office. He graduated to conducting impromptu stock checks (to catch potential thieves among the staff) before managing the branch in Kingston, a relatively unexplored satellite town just south of London. Yet it was home to a thriving student campus, and the Three Fishes pub, an enclave of American west coast and southern rock: ‘Everyone wore plaid shirts, drove VW vans and listened to The Grateful Dead,’ Ivo recalls.

The Kingston shop was first on the import van’s route from Heathrow airport, so Ivo was the first to lay his hands on albums such as Emmylou Harris’ Pieces Of The Sky, Tim Buckley’s Sefronia, and Bill Lamb and Gary Ogan’s Portland, pieces of exquisite rootsy melancholia that he’d sticker with recommendations and sell a hundred copies of each. Ivo became especially infatuated with Buckley’s five-octave range and equally audacious ability to master different genres. He began ordering album imports such as Spirit’s The Family That Plays Together and Steve Miller’s Children Of The Future because they had gatefold sleeves, made from thick board; the packaging was part of the appeal, tangible objects to have and to hold. Pearls Before Swine’s use of medieval paintings that were rich in symbolism but gave no indication of the music inside was another alluring draw.

But again Ivo became restless. Once he’d received the Criminal Compensation Board’s cheque for ?500 to fix his broken nose, Ivo forwent the operation (it was later paid for by the National Health Service) and went travelling with his friend Steve Brown, hitchhiking through France, taking the train through Spain and then the boat to Morocco, in the footsteps of those who’d sought out premium-grade hashish. After two months of beach-bum life, a cash-depleted Ivo was back in London, seeking work again. Steve Webbon, now managing the Fulham branch of a new record shop, Beggars Banquet, said the owners were looking for more staff.

One of the owners was Webbon’s old school friend Martin Mills. They’d stayed friends while Mills attended Oxford University; Webbon remembers hedonistic nights in student dens, where casual use of heroin was part of the alternative lifestyle, though, he adds, ‘Not Martin, he was more disciplined, not stupid like some others.’ Mills’ room would resonate to west coast classics: ‘The Byrds, Moby Grape, Love, The Doors,’ Webbon recalls. ‘English groups weren’t that inspiring – we were more interested in the next Elektra Records release. That was the kind of record label to follow, and ideally to be part of.’

Elektra had been founded in 1950 by Jac Holzman and Paul Rickolt; each invested $300. During the Fifties and early Sixties, the label had concentrated on folk music, but also classical, through its very successful budget Nonesuch imprint, sales of which helped to fund music of a more psychedelic nature, starting with the bluesy Paul Butterfield Band, Love, The Doors and a nascent Tim Buckley. The Nonesuch Explorer Series was a pioneer in releasing what became known in the Eighties as world music. Put simply, Holzman ran the hippest, coolest, trendiest and also the best record label around. But, like Ivo, he too got restless, and in 1970, Holzman sold his controlling share in Elektra, which became part of the Warner Brothers music group. Holzman stayed in charge until 1972, when it merged with Asylum Records, which specialised in west coast singer-songwriters, from Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt to Joni Mitchell and The Eagles. Politics and rivalries under the Warner umbrella made for a bumpy ride, but the quality of the music rarely wavered.

It’s very unlikely the Warners corporation would ever have considered housing its record companies in the rabbit warren of rooms and corridors that made up 15–19 Alma Road in Wandsworth, south-west London, where Martin Mills’ Beggars Banquet and associated labels have their offices. A suitably alternative, homespun space for the world’s most successful independent label group, Mills’ lawyer James Wylie once described the label’s operation as, ‘a Madagascar off the continent of Africa that is the music business, part of the same eco-system but with its own microclimate’.

Not even the success of Adele, signed to Beggars imprint XL, whose 2011 album 21 is the biggest selling album in the UK since The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper in 1967, has encouraged Mills to move – nor his half of a recent $27.3 million dividend based on his profit share. Mills also owns half of the Rough Trade and Matador labels, and all of 4AD. Mills – and Ivo – moved here in 1982, when more than 25 million sales would have been a ridiculous, stoned fantasy.

Born in 1949, Mills was raised in Oxford, and he stayed on to study philosophy, politics and economics at the prestigious Oriel College. Piano lessons had come to nothing when The Beatles and the Brit-beat boom arrived, though Mills says he favoured ‘the rougher axis’ of The Rolling Stones and The Animals, just as he enjoys live music much more than recordings, making him the opposite of concert-phobe Ivo. ‘I cared about music above anything else,’ he says, but when he failed to get a positive response to job requests sent to every UK record label he could find an address for, his upbringing demanded common sense. While taking a postgraduate degree in town planning, he shared a flat in west Ealing with Steve Webbon.

But he found he couldn’t give up on music. Scaling back his ambitions, Mills then began a mobile disco with a friend from Oxford, Nick Austin, who was then working for his father’s furnishing company. The pair named their enterprise Giant Elf (a riposte to J. R. R. Tolkien’s already iconic The Hobbit) before Mills claims they needed a new name after receiving too many hoax calls alluding to Giant Elf’s supposed gay connotation. A subsequent team-up with a friend’s mobile disco, called Beggars Banquet, provided the means.

Mills also drove a van for Austin’s father while signing on for unemployment benefit – ‘a desirable scenario back then,’ he smiles. But the benefit office forced him into a full-time job, and for two years, Mills worked for The Office of Population, Census and Surveys (managing the statistics for the Reform of Abortion act) but he landed a job at the Record & Tape Exchange, a well-known record shop trading in second-hand records in Shepherd’s Bush, not far from Ealing.

Soon, Mills and Austin were discussing running their own second-hand record shop, which would sell new records too. Each borrowed ?2,000 from their parents and, in 1974, opened Beggars Banquet in Hogarth Road, Earls Court. ‘It was a buzzing, backpacker type of place, with lots of record shops,’ says Mills. ‘But we’d stay open later than the others, until 9.30pm, selling left-field undergraduate stuff, west coast psychedelia, folk and country, but also soul, R&B and jazz-funk. We brought in Steve Webbon, who knew about record retail. By 1977, we had six shops.’

Beggars Banquet had given Ivo a job, and in a reversal of roles, he became Webbon’s assistant after the latter had moved to the Ealing branch. But so much of music, culture, and record retail was fundamentally shifting. The first real wave of opposition to the stagnating scenes of progressive, hard and west coast rock was the neo-punk of Iggy and The Stooges and the New York Dolls, which soon triggered a new wave of stripped-back guitars, centred around the CBGB’s club in the States (Patti Smith, Television) and the wilder exponents of so-called ‘pub rock’ in the UK (Doctor Feelgood, The 101ers). The first wave of London-based independent labels (Stiff, Chiswick, Small Wonder) sprang up to meet a growing demand, while Jamaican reggae imports were also rising. Not far behind was the new Rough Trade shop in west London’s bohemian enclave of Notting Hill Gate, whose founder Geoff Travis was to bolt on a record label and a distribution arm.

Beggars Banquet’s first expansion was as a short-lived concert promotions company. ‘We saw the opportunity for artists that people didn’t know there was demand for,’ says Mills, beginning with German ambient space-rockers Tangerine Dream in 1975 at London’s grand Royal Albert Hall. Only a year later, Mills says he saw a palpable shift in audience expectations while promoting the proto-new wave of Graham Parker, whose support band The Damned was the first punk band to release a single. ‘Punk turned our world upside down. No one wanted the kind of shows in theatre venues that we’d been promoting. People wanted grotty little places, so we stopped.’

A Beggars Banquet record label came next. The Fulham branch turned its basement into a rehearsal space for punk bands, one being London-based The Lurkers. A shop named after a Rolling Stones album was now primed to put rock ‘dinosaurs’ such as the Stones to the sword. Fulham branch manager Mike Stone had doubled up as The Lurkers’ manager. ‘Every label had a punk band now, and no one was interested in the band,’ says Mills. ‘So we released the first Lurkers single [‘Shadows’] ourselves. We had no clue how to, but we found a recording studio and a pressing plant in a music directory and we got distribution from President, who manufactured styluses.’

John Peel was an instant convert to punk, including The Lurkers, who sold a very healthy 15,000 copies of ‘Shadows’ on the new Beggars Banquet label. The profits funded Streets, the first compilation of independently released punk tracks. That sold 25,000, as did The Lurkers’ debut album Fulham Fallout.

Nick Austin spearheaded the talent-spotting A&R process. ‘He’d have ten ideas, and one was good, the rest embarrassing,’ says Steve Webbon. Subsequent Beggars Banquet acts such as Duffo, The Doll and Ivor Biggun (the alias of Robert ‘Doc’ Cox, BBC TV journalist turned novelty songsmith) were fluff compared to what Rough Trade and Manchester’s Factory Records were developing. ‘We were a rag-bag in the early days,’ Mills agrees. ‘A lot was off-message for punk. But our fourth release was Tubeway Army, after their bassist walked into the shop with a tape.’

Tubeway Army, marshalled by its mercurial frontman – and Berlin-era Bowie clone – Gary Numan, would catapult Beggars Banquet into another league, with a number 1 single within a year. But Numan’s demands for expensive equipment for the band’s first album, and other label expenses, stretched the company’s cash flow, and Mills says that only Ivor Biggun’s rugby-song innuendos (1978’s ‘The Winker’s Song’ had reached number 22 on the UK national chart) staved off near bankruptcy. Mills and Austin were businessmen, not idealists, so when they had to find a new distributor (the current operators Island had had to withdraw due to a licensing deal with EMI), they got into bed with the major label Warners. The licence deal meant that Beggars Banquet wasn’t eligible for the new independent label chart that would launch in 1980, but it did inject ?100,000 of funds. ‘It was an absolutely insane figure,’ says Mills. ‘How could Warners expect to be repaid?’

The answer to repaying Warners was Tubeway Army’s bewitching, synthesised ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’ and its parent album Replicas, which both topped the UK national chart in 1979. So did Numan’s solo album The Pleasure Principle, released just four months later. The Faustian deal effectively meant that Beggars Banquet became a satellite operation of Warners, even sharing some staff. ‘We’d become something we hadn’t intended to be,’ says Mills. ‘One reason we [later] started 4AD was that it could be what Beggars Banquet had wanted to be: an underground label, and not fragmented like we’d become.’

While working in the shop, Ivo had only been a part-convert to the punk revolution. ‘I liked some of The Clash’s singles but their debut album was so badly recorded, it didn’t interest me at all. But I’d seen Blondie and Ramones live, and I quickly came to enjoy punk’s energy and melody. But I didn’t need punk to wipe away progressive rock. I’d been listening to what people saw as embarrassing and obscure country rock – no one was interested in Emmylou Harris or Gram Parsons back then. But I just loved voices, like Emmylou, Gram and Tim [Buckley].’

Of the new breed, Ivo preferred the darker, artier, and more progressive American bands such as Chrome, Pere Ubu and Television, who had very little in common with punk’s political snarl and fashion accoutrements. Steve Webbon, however, appeared to more fully embrace the sound of punk and its attendant lifestyle. ‘Those customers that were still into the minutiae of country rock were very dull,’ he recalls. ‘And that music had become more mainstream and bland. I spent the Seventies on speed: uppers, blues, black bombers. It must have been wearing for Ivo.’

Ivo had been forced to take charge on those days when Webbon disappeared to drug binge or during his periods of recovery. Ivo himself dipped into another torpid period of indecision. ‘Being behind the shop counter, with these children coming in every night, their hair changed and wearing safety pins, was exciting, but it got pretty boring too. So I left again.’

This time, Ivo flew to find the Holy Grail – to California. His brother Perry was taking Latin American studies at the University College of Los Angeles and could provide a place to stay. When Ivo’s visa ran out after just a matter of months, he again went back to the devil he knew; Beggars Banquet rehired him to train managers across all its shops. But after just one hour in the job, he quit again: ‘I felt like a caged animal.’

After claiming unemployment benefit for six months, the local job centre forced Ivo to apply for a job as a clerical worker at Ealing Town Hall. He once again turned to Beggars, and Nick Austin – clearly a patient man – re-employed him to do the same training job. In the summer of 1979, Ivo was even allowed an extended holiday, returning to California, where he and his friend Dave Bates first conceived the idea of a record label, and of opening a record shop with a caf? in Bournemouth on the south coast. Both operations were to be named Freebase (friends of Ivo’s had claimed they invented the freebasing technique of purifying cocaine). Ivo even went as far as registering the name: ‘Thankfully, it never happened. Imagine being behind a company called Freebase. In any case, the shop and caf? was pure fantasy.’

Ivo’s first thought for the Freebase label was to license albums by the San Francisco duo Chrome, purveyors of scuzzy psychedelic rock/electronic collage. Instead, the band’s creative force Damon Edge suggested Ivo should buy finished product from him instead, which he was unable to afford.1 (#ulink_da64a847-1b8c-5a0f-8aa4-41f0f4cc10a5)

The next opportunity came after Alex Proctor, a friend from Ivo’s Oundle days who was working at the Earls Court shop, passed on a demo. Brian Brain was the alter ego of Martin Atkins, the former drummer of Sex Pistol John Lydon’s new band Public Image Limited (or PiL). Ivo had recommended his tape to Martin Mills, who didn’t show any interest. ‘But then I got talking to Peter Kent, who was managing Beggars’ Earls Court branch,’ Ivo recalls.

Ivo’s cohort in forming a record label now lives in the Chicago suburb of Rogers Park, two blocks from Lake Michigan’s urban beach. It’s his first ever interview. ‘I’ve always considered myself as a bit player on the side,’ says Peter Kent. ‘I know people who are just full of themselves, but I’m more private. And being a Buddhist, I like to live in the present rather than regurgitate the past.’ But he is willing to talk, after all. ‘It’s nice to leave something behind,’ he concedes.

Kent didn’t hang around for long in the music business, partly by choice but also due to illness (he has multiple sclerosis). Among other part-time endeavours, he works as a dog sitter, which would give him and Ivo plenty to chat about. But during the time that they worked together, Ivo says, he knew nothing about Kent’s private life.

Born in Battersea, south-west London, his family’s neighbour was the tour manager of the Sixties band Manfred Mann, which gave the teenage Kent convenient entry to London’s exploding beat music boom. Kent says he DJed around Europe while based in Amsterdam, ‘doing everything that you shouldn’t’. He adds that, ‘A friend was a doctor of medicine in Basle, who’d make mescaline and cocaine. Peter Kent isn’t my real name; Interpol and the drug squad were looking for me at one point. It’s a long story.’

Kent also says that British blues vocalist Long John Baldry was his first boyfriend before he dated Bowie prot?g? Mickey King who he first met, alongside Bowie, at the Earls Court gay club Yours or Mine. After returning from Amsterdam, Kent appeared to calm down when he started managing Town Records in Kings Road, Chelsea, next door to fetish clothing specialists Seditionaries, run by future fashion icon Vivienne Westwood and future Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren. He also ran a market stall-cum-caf? in nearby Beaufort Market, next to future punk siren Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex fame. By 1976, Kent had opened his own record shop, called Stuff, in nearby Fulham but it didn’t make a profit and so he took the manager’s post at Beggars Banquet’s Earls Court branch. The label’s office, and Ivo’s desk, was upstairs.

The origins of 4AD are contested. Kent says an avalanche of demos had been sent in the wake of Tubeway Army’s success: ‘Part of my job was to listen to them with the idea of forwarding the good ones to Beggars. I also said it was a great idea to start a little label on the side, and Martin said that’s what Ivo also wanted to do.’

Martin Mills recalls Ivo and Peter Kent approaching Nick Austin and himself with a plan, while Ivo sticks to the story he told Option magazine in 1986. ‘We’d regularly rush upstairs to convince Martin and Nick that they should get involved with something like Modern English, as opposed to what they were involved with. Eventually, Beggars got fed up with us pestering them and said, “Why don’t you start your own label?”’

Whatever the story, Mills and Austin donated a start-up fund of ?2,000. Kent got to christen the label, choosing Axis after Jimi Hendrix’s Axis: Bold As Love album. ‘Ivo and I clicked as people,’ says Kent. ‘It was like I was Roxy Music and he was Captain Beefheart, but we appreciated where each other was coming from. He was mellower; I was more outgoing. But I wouldn’t say I ever knew him well.’

‘Ivo and Peter were a good double act,’ recalls Robbie Grey, lead singer for Modern English, one of 4AD’s crucial early signings. ‘They were similar in their background too, neither working class, so straight away you were dealing with art college types.’

Steve Webbon: ‘Peter was great. Very tall, dry sense of humour. And he had all these connections. He wasn’t as into music as Ivo, he was more into the scene. He’d go to gigs while Ivo would more listen to your tape.’

Ivo: ‘Peter was so important to 4AD from the start. Most of the early stuff was his discovery. While I was running around servicing the other shops, he was the go-getter. He knew people. I liked everything enough to say yes, but I didn’t know what I was doing.’

One part of the plan was for Axis to play a feeder role for the Beggars Banquet label, so that those artists with commercial ambition could make use of Beggars’ distribution deal with Warners. Another idea was to launch Axis with four seven-inch singles on the same day: ‘To make a statement, and to establish an imprint,’ says Ivo. ‘Other independent labels at that point, such as Factory, were imprints. It meant something.’

Factory’s first release, A Factory Sampler, had featured four bands, including Joy Division and Sheffield’s electronic pioneers Cabaret Voltaire. Axis’ first quartet, simultaneously released on the first business day of 1980, wasn’t quite as hefty. Nor did it include Brian Brain, which would have instantly given the label a newsworthy angle, or another mooted suggestion, Temporary Title, a south London band that used to rehearse in Beggars’ Fulham basement, whose singer Lea Anderson was a ‘floating’ Saturday shop assistant across the various Beggars Banquet shops. Instead, out of the pile of demos emerged three unknown entities, The Fast Set, Shox and Bearz, and one band that had released a single on east London independent Small Wonder: Bauhaus, who was to save Axis from the most underwhelming beginning.

The single given the honour of catalogue number AXIS 1 was The Fast Set’s ‘Junction One’. London-based keyboardist David Knight was the proud owner of a VCS3 synth, popularised by Eno, whose demo was played in the Earls Court shop by his friend Brad Day who worked there on Saturdays. ‘Peter Kent said if I wanted to record an electronic version of a glam rock track, he’d release it on this new label,’ recalls Knight. ‘The Human League had covered Gary Glitter’s “Rock And Roll”, and there were lots of other post-modern, semi-ironic interpretations around. I knew T. Rex’s “Children Of The Revolution” had only two chords, which suited me. Peter put me in a studio to record it, but he needed another track, which I knocked out on the spot, which became the A-side. I don’t know why.’

At very short notice, Knight and three cohorts played a show at Kent’s request. Budding film director John Maybury (best known for his 1998 Francis Bacon biopic Love Is the Devil) projected super-8 images on to them and named them The Fast Set, because the quartet were so immobile on stage. Maybury also designed the cover of ‘Junction One’. The Fast Set’s synth-pop had a bit of early Human League’s sketchy pop but not its vision or charm. ‘For starters, I was no singer,’ says Knight. ‘My vocals were appalling!’

AXIS 2 and AXIS 4 were demos that had been posted to the Hogarth Road shop. ‘She’s My Girl’ was by Bearz, a quartet from the south-west of England that wasn’t even a band, says bassist Dave Gunstone. ‘The singer John Goddard and I had an idea to make a record – we liked the new wave sound, but we didn’t even have songs before we booked the studio. We found a drummer, Mark Willis, and David Lord produced us and played keyboards. I was a signwriter for shops and vans then – and you can hear I’m not a musician. But Ivo called to say he was interested in signing us. We went up to see him and Peter – to be in the office with Gary Numan gold discs on the walls, it was dream come true.’

They called themselves The Bears until Ivo (who says it would have been Peter Kent) pointed out other bands had already used the name, ‘so he said “stick a z on the end”,’ says Gunstone. ‘Neo-psychedelic vocals over an attractively lumpy melody’ (NME) and ‘nostalgia pop’ (Peter Kent) are fair appraisals of the song, given the dinky Sixties beat-pop and Seventies bubblegum mix, while the B-side ‘Girls Will Do’ was tauter new wave.

Shox were also hopeful of a stab at success via the new wave conceit of a misspelt name – though the photo on the cover of vocalist Jacqui Brookes and instrumentalists John Pethers and Mike Atkinson in one bed was horribly old school. The most prominent British weekly music paper, New Music Express (NME) also approved of ‘No Turning Back’: ‘Fresh and naturally home-made, like The Human League once upon a time’. Peter Kent’s comment, ‘I have no memory of it whatsoever’, also hits the mark.

AXIS 3, ‘Dark Entries’, was an altogether different story. Peter Kent recalls being in the Rough Trade shop. ‘I was buying singles for Beggars Banquet, and Geoff Travis was there, playing some demos. I heard him say he didn’t like it, and I said, “Excuse me?” Geoff said I could take it. The energy was unbelievable, and the sound was so different from everything else around. Forty-eight hours later, I was in Northampton to meet Bauhaus.’

Ivo: ‘If Peter did go to Northampton, that was another thing that he didn’t tell me! I first met Bauhaus in the Earls Court shop where Peter had intercepted the tape they were intending to deliver to Beggars Banquet. Peter came to find me in the restaurant over the road and insisted I come back immediately to listen to it and meet the band.’

According to Bauhaus’ singer Peter Murphy, ‘Peter said, “I’m having you lot”. Ivo didn’t want us. That’s what Peter said at the time. Ivo’s a mardy bugger! And really sarcastic [laughs]. But when we walked into the Beggars office, Ivy [Murphy’s affectionate nickname for Ivo] was working there, and he looked at us after hearing the music and said yes!’

Via a Skype connection to Turkey’s capital Istanbul, where Murphy has lived since marrying his Turkish wife and following the Islamic belief of Sufism, the former Bauhaus singer still looks sleek and gaunt, his celebrated ‘dark lord’ persona intact. Traffic whirs away in the background, but it cuts out when Murphy puts on ‘Re-Make Re-Model’ from Roxy Music’s epochal 1972 album debut, presumably to set the scene for our conversation, by showcasing Bauhaus’ roots in both glam and art rock.

‘I was fifteen,’ Murphy begins, ‘and I didn’t know if it was male or female, but I saw this pair of testicles peaking out under a Kabuki outfit, and it was the most erotic moment. It felt angelic.’ The photographic object of his affection was David Bowie, in his Ziggy Stardust leotard. Roxy Music’s synthesiser magus Brian Eno, says Murphy, ‘was maybe even more magical, awesome in that raw, lo-fi way, the drums on his solo records so flat and thick and stocky, with none of that fucking reverb bollocks that Ivo would swamp things in!’

The Bauhaus siblings, David and Kevin Haskins, both now live in California – David J, as the bassist calls himself, is in Encinitas, 95 miles from Kevin Haskins Dompe (he’s since bolted on his wife’s maiden name) in Los Angeles. Both willingly testify to a similarly shared epiphany – July 1972, when Bowie – in the guise of Ziggy – sang ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops. ‘I was hooked, and I knew I had to do this myself.’

There’s one missing voice – guitarist Daniel Ash. Though he lives in California as well, he hasn’t communicated with any of his former bandmates since the band’s 2008 album Go Away White. Ash, the others say, prefers tinkering with his beloved motorbikes over any remembrance of the past.2 (#ulink_f7565457-eb82-51eb-9150-630df1b84812)

Playing guitar, David J had graduated from his first band, Grab a Shadow, and having encouraged Kevin – still just thirteen – to learn the drums, they’d joined Jam, a hard rock covers band. ‘And then punk happened,’ says Haskins Dompe. ‘David took me to The 100 Club to see the Sex Pistols, The Clash and the Banshees. The next day I cut off my hair and wore my paint-splashed polyester pyjamas to art school.’

After the demise of the pair’s short-lived punk band The Submerged Tenth, David J had bumped into fellow art school student Ash, who he’d known since kindergarten. ‘We clearly had a connection,’ says David. ‘We both loved dub reggae, and Bowie.’ Haskins and Ash subsequently formed The Craze, which, Haskins Dompe says, ‘played new wave power-pop, which Daniel didn’t like, so that ended’. Ash asked Haskins Dompe to join a new band fronted by Ash’s old school friend Peter Murphy, but excluding David J. ‘Daniel felt David’s ideas were too strong, but he relented,’ says Haskins Dompe. ‘I could see the chemistry between them.’

David J had watched the others rehearse. ‘They were so streamlined and stark, and Peter had such charisma, and looked amazing. They had a bassist, but his looks and personality didn’t fit, so I joined.’

Peter Murphy: ‘David was sensitive, smart, self-interested, a dark horse. Kevin could be narky and uppity, but he was our sweet angel. I was very overpowering but we were respectful of each other, though there was a lot of unspoken, repressed tension.’

The battle of wills that marked Bauhaus to the end produced the necessary sparks at the start. Written only weeks after David J joined, the band’s debut single ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ was a cavernous, dub-enhanced nine-minute drama with the epic mantra, ‘undead, undead, undead,’ in honour of Bela Lugosi, the Hungarian actor most famous for his 1931 portrait of Dracula. ‘We surprised ourselves, because it was ambitious and didn’t follow anyone else,’ says David J. Every major label (and Stiff) declined to release it, before the fledgling London independent label Small Wonder stepped in. ‘Theirs was the only response that didn’t think the track was too long.’

Thirty-four years on, ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ remains Bauhaus’ signature classic; it hung around the new UK independent singles chart (launched two weeks after Axis) for two years. It also helped spawn a genre that proved to be as contentious for the band as it was for the future 4AD. It’s said that the term ‘gothic’ was used by Factory MD Tony Wilson to describe his own band Joy Division, but it was also applied to the ice queen drama of Siouxsie and the Banshees. Soon enough it would be shortened to ‘goth’, and wielded as a pejorative term, to describe an affected version of doom and angst.

The problem was, as Ash said, goth came to define bands with ‘too much make-up and no talent’. Bauhaus were undeniably talented, but Murphy had a habit of shining a torch under his chin as he prowled across the stage. This was fine by Kent: ‘I wanted more than people just standing there on stage, and Peter was already one of the best frontmen,’ he says. Murphy relishes the memory of a Small Wonder label night at London’s Camden Palace, ‘me in a black knitted curtain and jockstrap,’ he recalls. ‘We scared the fuck out of everyone that night, all these alternative ?ber-hippies moaning about everything. After punk, everybody ran out of things to moan about.’

Actually, the opposite was true. Post-punk had plenty of targets to kick against in 1980 and its bristling monochrome was a suitable soundtrack to the economic and social depression of an era presided over by the hate figure of Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher: tax increases, budget cuts, worker strikes, nuclear paranoia, Cold War scare-mongering and record post-war levels of inflation (22 per cent) and unemployment (two million). But goth bands didn’t articulate social injustice or political turmoil. This version of disaffection and dread was more Cabaret, an escape from the gloom, with lots of black nail varnish. Bauhaus’ ‘Dark Entries’, for example, was inspired by the decadent anti-hero of Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. ‘A story of great narcissism and esoteric interior,’ says Murphy. ‘A rock star’s story.’

Axis’ founders didn’t appear driven by causes or campaigns either. Ivo didn’t favour political agitators such as The Clash or Gang of Four, but more the open-ended oblique strategies of Wire or the acid psychodrama of Liverpool’s Echo & The Bunnymen. In fact, Ivo felt that the name Axis had unwanted political connotations. ‘Peter [Kent] may have been thinking of Hendrix but, for me, Axis related to [Nazi] Germany, like Factory and Joy Division. It was a stupid name.’

It was a stroke of fortune that the label was forced into changing its name before the imprint, or the association, stuck. An existing Axis in, of all countries, Germany, read about the launch of the UK version in the trade paper Music Week; the owners allowed all the remaining stock on the UK label to be sold before they had to find a new name. ‘4AD was grasped out of the air in desperation,’ says Ivo.

A flyer that freelance designer Mark Robertson had laid out to promote the launch of Axis worked on the concept of a new decade and a new mission. In descending order down the page was written:

1980 FORWARD

1980 FWD

1984 AD

4AD

‘What I loved about 4AD was that it meant nothing,’ Ivo recalls. ‘No ideology, no polemic, no attitude. In other words, just music.’

1 (#ulink_c7f10a8d-aee0-5c2d-8ea9-f780c85cb260) After starting 4AD, Ivo did import copies of Chrome’s second album Half Lip Machine Moves before introducing the band to Beggars Banquet, which released the band’s next three albums, starting in 1980 with Red Exposure.