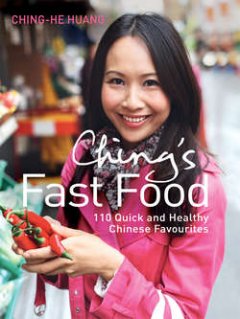

ChingТs Fast Food: 110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites

јвтор:Ching-He Huang

» ¬се книги этого автора

∆анр: кулинари€

“ип: нига

÷ена:344.57 руб.

язык: јнглийский

ѕросмотры: 199

”ѕ»“№ » — ј„ј“№ «ј: 344.57 руб.

„“ќ ј„ј“№ и ј „»“ј“№

ChingТs Fast Food: 110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites

Ching-He Huang

With her trademark passion, TV star chef Ching-He Huang brings an exciting dimension to Chinese cooking. Confidently fusing Chinese and Western cultures in over 100 quick and easy dishes bursting with flavour, Ching's fresh and healthy take on the Chinese takeaway, without compromising on taste, has revolutionised Chinese cuisine.Ching's love and appreciation of Chinese cooking has already seen her previous cookbooks, Chinese Food Made Easy and Ching's Chinese Food in Minutes, reach bestseller status and her BBC TV series receive rave reviews. Now paying homage to the authentic Chinese takeout with her third cookbook, Ching's Chinese Takeaway, Ching makes Chinese food refreshingly accessible and deftly removes the stigma attached to the humble takeaway.From the traditional Chicken Chow Mein to adventurous Cantonese style steamed Lobster with Ginger Soy Sauce; and with lighter dishes such as Yellow Bean Sesame Spinach to Chilli Bean Braised Beef with Coriander and steamed Mantou Buns designed to fill empty stomachs, Ching offers a diverse selection of new and delicious recipes for every occasion and taste.Interspersed with childhood anecdotes, Chinese superstition and etiquette and original suggestions for exciting variations on classic recipes, Ching takes us on a culinary journey that delightfully blends ancient and modern, yin and yang, experimentation and intuition, and ends with perfectly balanced and tantalizing dishes that will inspire even the most stalwart takeaway devotees to get cooking.

ChingТs Fast Food

110 Quick and Healthy Chinese Favourites

Ching-He Huang

For all my family, friends, fans and Сgue-renТ, thank you so much from my heart. A little bit more of me to you, with love.

Contents

Introduction (#ulink_833d0b75-c2f1-5531-82dc-720e3c81605b)

Breakfast (#ulink_970b3fca-ace9-5aae-81b7-58d4bfb6c58d)

Soups (#ulink_a46d8773-f11a-53d9-90d5-30825fa4c89d)

Appetisers (#ulink_4859cb40-9889-555e-a727-ce46b035c2b0)

Chicken & Duck (#litres_trial_promo)

Beef, Pork & Lamb (#litres_trial_promo)

Fish & Shellfish (#litres_trial_promo)

Vegetarian (#litres_trial_promo)

Specials (#litres_trial_promo)

Rice (#litres_trial_promo)

Noodles (#litres_trial_promo)

Dessert (#litres_trial_promo)

Equipment (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Searchable Terms (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Enough is enough.

Chinese food doesnТt get the recognition it rightly deserves in the Western world. French, Japanese, even Korean cuisine all receive high praise from food critics in the press, but Chinese food remains underappreciated. Chinese cuisine can be just as complex or as basic as any other cuisine. It has so much to offer and has given so much already. It has travelled all over the world with immigrant Chinese families and its influence can be seen in the food cultures of many different countries, from Asia Ц Japan, Thailand and Vietnam Ц to Indonesia and the West.

Did you know that there are more takeaway Chinese restaurants in America than every McDonaldТs, Burger King and KFC put together? In the UK there are more than 15,000 Chinese takeaways and restaurants, and Chinese takeaways have officially overtaken Indian takeaways as the nationТs favourite type of meal to order in every week. In America, Chinese restaurants first developed to provide food for the railway workers in the 19th century. Immigrant chefs had to use local ingredients to cater for their customersТ tastes, so dishes were given a name and number and served with a very un-Chinese roll and butter. These were the circumstances in which Chinese takeaway menus were first devised.

During this period and over the years, many inventive takeaway dishes were created, including egg foo yung (omelette served with gravy), chow mein (stir-fried noodles), chop suey (leftovers in a brown sauce), crispy beef and General TsoТs chicken (battered chicken in a spicy sweet ketchup sauce) Ц dishes as well loved in Britain and America as shepherdТs pie, or steak and chips.

If you are a fan of your local Chinese takeaway and you then travel to China, my guess is that you will experience more than a culture shock, for the food will seem very unfamiliar. Some English businessmen have admitted to me that they fill their suitcases with crisps and other goodies when they travel to China because they cannot stomach the food there! If you go with an open mind, however, youТll discover a whole new culinary world. Should you be lucky enough to dine with Chinese friends at their favourite Chinese haunt, youТll find the menu will be dismissed, there will be a few exchanges of Cantonese or Mandarin, some quick scribbles by the waiter and youТll be treated to such delicacies as clay pot chicken, braised chickenТs feet, Сfish-fragrantТ aubergine, steamed sea cucumbers and baked salted chicken.

But there are signs that the disparity between takeaway food and СrealТ Chinese cuisine is lessening. China has opened up over the last decade and there are now many more opportunities for travel to and from the country. The internet has helped too. As a result, more people are beginning to appreciate that Chinese cooking is much more than what is served at their local takeaway.

Chinese takeaway food has also recently moved on and become more exciting. There are more dim sum restaurants than ever, for instance, and while Cantonese cuisine is still the most widely served outside China, establishments offering dishes from other regions are sprouting up all over the place Ц no longer just Cantonese, but Sichuanese, Hunanese, Taiwanese and Shanghainese. Chinese takeaway food remains a huge phenomenon. Chinese takeaways can be found all over the world and each one has a unique story attached to it. Often you will hear how someoneТs grandfather started the takeaway, or how the place has been in the same family for generations. By contrast, others have changed ownership many times, serving as a golden goose for perhaps a decade before being passed on.

When my family first arrived in England and we stood waiting for a train, I remember an elderly couple asking my father whether we owned a takeaway or Chinese restaurant. That was two decades ago when it was the norm for newly arrived Chinese families to open a takeaway. The majority of my fatherТs friends in the Chinese community in London owned takeaways.

In hindsight, my father thought he probably would have been more successful had he followed suit rather than going into the importЦexport business. At the time, however, he felt this was the right thing to do, as my grandparents were proud that their eldest son had graduated with a business degree and were prejudiced against him working in catering, which was considered laborious and low skilled (still the view in China today).

My first takeaway experience was in England Ц at a small place on the Fortune Green Road in North London. Prior to that I had never had food from one. My mother is a great cook, and when we lived in South Africa (before travelling to England), she made all the meals. Her recipes were mainly Chinese but with a South African twist, such as a stir-fried or traditional stewed dish served with miele pap (rather like polenta) instead of boiled rice.

In fact, there were no Chinese takeaways that I can recall during my time in South Africa. There was only one Chinese supermarket in JoТburg at the time, which my mum would religiously frequent every week to stock up on provisions for her Chinese larder.

In England, by contrast, there were a lot more takeaways and one busy weekday, shortly after we had arrived in the country, we ordered from our local. The experience wasnТt too bad, but Mum found it overly expensive and the fried rice not up to standard, so she turned her nose up at it and we never ordered from there again. The takeaway remains in business, however: last time I passed, it was still there. Mum preferred the Cantonese restaurant, the Water Margin, on Golders Green Road, and we went there when she wasnТt in the mood for cooking. The restaurant became the place where I could meet my friends (or a date) for a quick Saturday lunch while satisfying my craving for Cantonese roast duck on rice.

Chinese takeaways are the Сfast foodТ of Chinese cuisine. A takeaway is where you would go to get your fried spring rolls, fried wontons, special fried rice or beef with greens. It is usually a lot more salty and oily than home-cooked Chinese food, in which dishes are a lot simpler, less rich and better balanced. It is no wonder that Chinese takeaways have created a bad name for themselves with many using high levels of monosodium glutamate to enhance the flavour. Although MSG is a natural substance, found in many foodstuffs, used as an additive it can have adverse effects. I personally have an intolerance to it, suffering from heart palpitations and a dry throat.

To me, if you use the freshest ingredients, you donТt need MSG because the dish will be full of flavour, especially if those ingredients are in season and at their very best. Many manufacturers of Chinese or Asian condiments often add MSG, and I have found that a small amount within a sauce is fine, but commercial sauces can contain quite a bit. Try and find ones that donТt have MSG and contain ingredients that are as natural as possible. Best of all, create your own sauces Ц in this book IТll show you how to use store-cupboard ingredients to make your own. It is true of all cuisines that the foods you cook yourself at home will be healthier and lighter than any takeaway food. In fact, a recent report showed that a meal cooked at home contains on average 1,000 fewer calories than its takeaway/restaurant equivalent and considerably less salt. Even though my grandmother was partial to a little Сgourmet powderТ (MSG) from time to time, she always practised what she preached Ц to be certain of what youТre eating, it is better to cook the food yourself.

ThatТs not to say that IТm not partial to a Chinese takeaway myself; indeed, there is a good one near where I live in North West London. I happen to know the owner and have been to the factory where the special 11-spice powder they use for their crispy aromatic duck is lovingly ground, and itТs so good! When I donТt have anything in my fridge or want to give myself time off in the kitchen, I just give them a ring and order number 15. But unless you know the establishment well, itТs like takeaway roulette, and weТve all had a bad takeaway experience at some time or another. If you have a reliable local takeaway, support the owners and treat them like family!

I actually love Chinese food in all its forms Ц Americanised, anglicised, even bastardised. I recently had the pleasure of trying Chinese chicken salad American-style and I could see the attraction in the sweet orange sauce coupled with crispy fried wonton skins, crunchy lettuce and chicken strips. Yes, God forbid, I have even had a craving for it since! (I blame it entirely on the sugary sauce.) There is beauty in Chinese takeaway food that is cooked well Ц even a pretty standard dish like sweet and sour pork balls. I know some expats living Hong Kong who demand to have some of the anglicised takeaway stuff and would import it if they could. It is simply a matter of taste. And what most fascinates me is how thousands of people all over the world are united in their love of Chinese takeaway food, while the forefathers of this invention were completely unaware that they were the pioneers of Chinese fast food and the very best in their field. It is an amazing achievement when you think about it: these days R&D (research and development) chefs get paid six-figure sums to come up with what they did.

In my quest to share my love and appreciation of Chinese food, I myself have been blamed for Сdumbing downТ Chinese cuisine for the Western palate in my attempt to whet peopleТs appetite for it. But I much prefer to see it as Сcreative fusionТ. If I remained true to the Chinese classics, I would be a copycat cook and not a progressive one. A cookТs job in my opinion is to be creative and push the boundaries of their cuisine and never stop experimenting.

Yes, classics are good, but classics at one point in history came from somewhere too. They were once new Ц someone invented them, and if they had never experimented, we wouldnТt be enjoying those dishes today.

And are classic dishes the only authentic ones? I prefer the term СheritageТ. Dishes can have heritage and influence, but they are not necessarily СauthenticТ because the question would be, authentic to whom? Authenticity is a matter of perspective. Chinese takeaways have become such a staple of so many different countries that you could argue that they are just as authentic within immigrant Chinese cooking as the older, classic dishes.

I am always being asked for takeaway menu recipes, so here is my book on the subject. DonТt accuse me of not knowing my xiao long bao from my char siu bao Ц because I do and I can make both. I want to share my love of Chinese takeaways and show how, cooked well, they can hold their own with the other great cuisines of the world. People also ask me whether I cook other types of food at home, and I certainly do. In fact, I have a soft spot for Lebanese cuisine, and I love Italian and Indian. But my vocation and career is making Chinese food Ц and please excuse the generic word СChineseТ, for there are over 34 regions in China with over 54 different dialects and each region has a unique way of preparing food. So until I master all the Chinese dishes there are to be mastered and explored, I wonТt be able to venture properly into other cuisines. Chinese cooking alone could keep me going for more than a lifetime.

If you are Chinese and, like my father, snobbish about Chinese takeaways, my hope is that, after reading these recipes, you will be cooking and feeding them to your kids instead of the dog and you will feel encouraged to embrace them as part of your culture and be proud of them.

Chinese takeaway cuisine is perfectly acceptable at home too, and I want to prove that, when cooked correctly, it can be the healthiest, most economical and delicious food you have ever eaten. With many low-fat dishes and using plenty of fresh vegetables and lean meat and fish, itТs also good for those who are worried about keeping slim. If you are vegetarian, Chinese food has a huge array of bean curd and Сmock meatТ recipes made from wheat gluten. Equally, if you are allergic to wheat or gluten or to monosodium glutamate, you can buy soy sauces that are wheat-free and condiments that donТt contain MSG. If you have a nut allergy, use vegetable or sunflower oil instead of groundnut oil, and if you are watching your salt intake you can substitute a low sodium, light soy sauce. I would also advise using organic or free-range eggs and meat wherever possible.

With this book, I want to give you my 21st-century version of the Chinese takeaway, inspired by this favourite fast food. I want to demonstrate how I think Chinese takeaway dishes should be cooked at home. I will look at all the offerings, whether healthy or unhealthy, give my view on them, share tips with you and show you lots of easy recipes that can be cooked far more quickly than it would take you to order your favourite takeaway dish. I will share with you my knowledge of flavour pairings to get the best out of your Chinese store cupboard (see the box above for my top ten ingredients) and introduce some new ways of eating and cooking Chinese food. In addition, I want to show you how Chinese takeaway dishes, when cooked with the freshest ingredients you can lay your hands on (coupled with the right culinary techniques), is a far superior Сfast foodТ than any other cuisine in the world. If I owned a takeaway, the dishes in this book are the ones youТd find on my menu.

Enough said. Less talk and more cooking!

MY TOP TEN ESSENTIAL CHINESE STORE-CUPBOARD INGREDIENTS:

1. Light soy sauce

2. Dark soy sauce

3. Shaohsing rice wine

4. Toasted sesame oil

5. Five-spice powder

6. Sichuan peppercorns

7. Chinkiang black rice vinegar

8. Clear rice vinegar

9. Chilli bean sauce

10. Chilli sauce

Breakfast

When I first arrived in South Africa, I was five and a half. After a tearful goodbye to the rest of the family, my mother, brother and I packed our bags to join my father, who had already left to set up a bicycle business in South Africa. In Taiwan he had been working as a manager in a building company and hated his job. So when by chance he met Robert (СUncle RobertТ to us) and the South African convinced my father to set up in business with him, he jumped at the idea. We liked Uncle Robert: we had met him only once, but he had taken us to a pizza restaurant and given me a cuddly racoon toy from South Africa. Despite no previous business experience and not knowing a word of English, my father moved us all over there on a whim. It was to be one of the scariest but most fulfilling adventures of my childhood.

At Uncle RobertТs insistence, we stayed on his farm just outside JoТburg. He and his wife Susan accommodated us in a converted barn on their plot of land, which extended for acres and acres. They even had a mini reservoir with their own supply of water and they kept horses and several Rhodesian Ridgebacks. Aunty Susan was a welcoming lady. The day we arrived, while my mother was unpacking and tidying up the barn, she took us food shopping. My brother and I were taken to the most enormous building we had ever seen. It was a hypermarket. Back in Taiwan, I hadnТt even been to a supermarket before. Even in Taipei, the only modern outlets we had were 7-Eleven convenience stores. The only place like it in our experience was the local wet market my grandmother used to take us to in the village, so this vast building was a shock.

My brother and I went up and down the aisles, admiring the rows and rows of packaged ingredients. There were even fish tanks with fresh lobsters and crabs. Aunty Susan guided us to a large chilled section; I remember feeling really cold. She pointed to the shelves and gestured to us to pick something, so I picked a small light brown carton and my brother picked a dark brown one. We hadnТt a clue what we had chosen. The rest of that shopping trip is now hazy, although I remember plenty of boxes and paper bags being carted to Aunty SusanТs large fancy kitchen.

She handed us each a teaspoon and we left her to her unpacking. I opened the foil lid of my carton and took a small mouthful, and my brother did the same. The taste was creamy and sour but also sweet; I had no idea that I had picked a caramel-flavoured yoghurt and my brother a chocolate one. We were used to our Yakult, but this was an entirely new experience. We werenТt sure we liked it, but we went back to the barn and showed the yoghurts to Mum. She took a small mouthful and then spat it out: СPai kee yah!Т (СItТs gone off!Т in Taiwanese). She stormed over to Aunty SusanТs and started СcommunicatingТ with her. They couldnТt understand what each other were saying; in the end my mum threw the pots in the bin! Aunty Susan looked bewildered and shrugged her shoulders. I thought Mum was rude, but I didnТt dare say anything. The next day Aunty Susan dropped by as Mum was making us fried eggs for breakfast. She brought over these dark green, what my mum called hulu- or gourd-shaped vegetables. Aunty Susan sliced one in half to reveal a large round stone in the middle; she then scooped the green flesh out of one of the halves and smeared it on to a slice of brown bread she had brought over with her. She gestured to my mother to take a bite. My mum had a taste and shook her head, saying, СBu hao chiТ (СNot good eatТ). СAvocaaaa-do,Т said Aunty Susan, then smiled, patted us on our heads and walked out the door.

Despite not liking the taste, my mother hated wasting food, so she placed the eggs she had been frying on the avocado bread, drizzled over some soy sauce and told us to eat it. She didnТt have any herself. Over time, however, avocados became one of my MumТs favourite foods. She now lives permanently in Taiwan, where avocados are hard to get and expensive. When we Skype, she will often ask, СYou still eating avocados?Т That recipe, washed down with a glass of soya milk, is now one of my favourite dishes for breakfast.

You will notice that my recipes, like yin and yang, tend to be very black and white, very Western or very Chinese, but when recipes work together, East and West can be balanced, like the takeaway menu, to give amazing, what I like to call Сfu-sianТ-style food. You may not associate breakfast with Chinese takeaways, but there are many eateries all over Asia that serve warming breakfasts, which can be bought on the way to school or work. In addition to Western-style sandwiches, these small eateries (and sometimes street stalls) serve you-tiao, or fried bread sticks, with hot or cold soya milk (sweetened or unsweetened), mantou (steamed buns) with savoury or sweet fillings and of course steaming bowls of congee in a variety of flavours. If I had a takeaway or diner, I would definitely include a breakfast menu, and I would serve a variety of Western and Chinese-style treats Ц just like the snack stalls in the East.

Toast with avocado, fried eggs and soy sauce

Aunty Susan, whom we stayed with when we first arrived in South Africa, gave my mother two ripe avocados, smearing one of them on some bread. Mum thought it was odd to serve a vegetable in this way, but soon she started to make us fried-egg sandwiches for breakfast with a generous slathering of avocado. Now I donТt hesitate to make this for breakfast, spreading slices of toast with a chunky rich layer of ripe avocado, topped with poached or fried eggs (preferably sunny side up) and a drizzle of light soy sauce. If I had my own takeaway or diner, this would certainly feature on the menu!

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 3 minutes

SERVES: 1

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

2 large eggs

2 slices of seeded rye bread

? ripe avocado (save the rest for a salad later), stone removed and flesh scooped out

Drizzle of light soy sauce

Salt and ground black pepper

1. Heat a wok over a medium heat until it starts to smoke and then add the groundnut oil. Crack the eggs into the wok and cook for 2 minutes or to your liking. (I like mine crispy underneath and still a bit runny on top.) Meanwhile, place the bread in the toaster and toast for 1 minute.

2. To serve, place the toast on a plate and spread with the avocado flesh. Place the eggs on top and drizzle over the soy sauce, then season with salt and ground black pepper and eat immediately. This is delicious served with a glass of cold soya milk, a cup of rooibos tea with a slice of lemon or some freshly pressed apple or orange juice.

Basil omelette with spicy sweet chilli sauce

In Taiwan, there are many night market stalls that sell the famous oyster omelette. A little cornflour paste is stirred into beaten eggs, then small oysters are added and sometimes herbs. When the eggs have almost set, a spicy sweet chilli sauce is drizzled over the top, making a comforting, moreish snack. I adore this dish, but it is hard to get fresh small oysters, so I make a vegetarian version sometimes for breakfast, using sweet basil, free-range eggs and adding my own spicy sweet chilli sauce, made using condiments from my Chinese store cupboard.

PREP TIME: 3 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes

SERVES: 1

3 eggs

Large handful of Thai or Italian sweet basil leaves

Pinch of salt

Pinch of ground white pepper

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

Handful of mixed salad leaves, to garnish

FOR THE SAUCE

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

1 tsp of vegetarian oyster sauce

1 tbsp of mirin

1 tsp of tomato ketchup

1 tsp of Guilin chilli sauce, or other good chilli sauce

1. Make the spicy sweet chilli sauce by whisking all the ingredients together in a bowl, then set aside.

2. Crack the eggs into a bowl, beat lightly and add the basil leaves, then season with the salt and ground white pepper.

3. Heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke and then add the groundnut oil. Pour in the egg and herb mixture, swirling the egg around the pan. Let the egg settle and then, using a wooden spatula, loosen the base of the omelette so that it doesnТt stick to the wok. Keep swirling any runny egg around the side of the wok so that it cooks. Flip the omelette over if you can without breaking it, then fold and transfer to a serving plate, drizzle over some of the spicy sweet chilli sauce and serve with a garnish of mixed leaves.

Smoked salmon and egg fried rice

This is my classic breakfast recipe Ц itТs so good I had to share it with you. Make sure you add the smoked salmon after the rice, as the rice acts as a cushion, helping the salmon not to catch on the side of the wok and flake into tiny pieces.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 7 minutes

SERVES: 1

1? tbsps of groundnut oil

2 eggs, beaten

75g (3oz) frozen peas

300g (11oz) cooked leftover cold jasmine rice (see the first tip in Rice) or freshly cooked long-grain rice (see the tip below)

150g (5oz) smoked salmon, sliced into strips

1Ц2 tbsps of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of toasted sesame oil

Pinch of ground white pepper

1. Heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke and then add 1 tbsp of the groundnut oil. Tip the beaten eggs into the wok and stir for 2 minutes or until they are scrambled, then remove from the wok and set aside.

2. Return the wok to a high heat and add the remaining groundnut oil, allowing it to heat for 20 seconds. Tip in the frozen peas and stir-fry for just under a minute. Add the cooked rice and mix well until the rice has broken down.

3. Add the smoked salmon slices and toss together for 1 minute, then add the scrambled egg pieces back into the wok and stir in. Season with the soy sauce (to taste), the toasted sesame oil and white pepper and serve immediately.

CHINGТS TIP

If using freshly cooked rice, use 150g (5oz) of uncooked long-grain rice, such as basmati, rinse it well and then boil in 300ml (? pint) of water, cooking until all the water has been absorbed. This will take an extra 20 minutes.

ALSO TRY

If you are not a fan of fish, then used smoked bacon lardons instead Ц cook them until crispy before adding.

Cumberland sausage, green pepper and tomato fried rice with pineapple

A few years ago, I came up with bacon and egg fried rice, which my friends adored. This one is a follow-on from that. ItТs the ultimate brunch dish Ц so easy to do on a lazy Sunday. Children will love it and the neighbours will hate you as they spy enviously over the fence while you tuck in. This is my equivalent of a fry-up, but avoid using too much oil in this dish, as the sausages are quite fatty. ItТs best to pour the excess fat away, as revealed below. For a healthier version of this dish, you could mix in some spinach leaves, if you liked, and serve with a simple garden salad.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

COOK IN: 7 minutes

SERVES: 4

2 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

2.5cm (1in) piece of root ginger, peeled and finely sliced into matchsticks

6 Cumberland sausages (350g/12oz in total), chopped into 1.5cm (

/

in) rounds

1 green pepper, deseeded and cut into 1.5cm (

/

in) dice

1 very large ripe beef tomato, cut into chunks

500g (1lb 2oz) cold leftover cooked jasmine rice (see the first tip in Rice) or freshly cooked long-grain rice (see the tip below)

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of chilli oil

Juice of 1 lemon

Large handful of ripe pineapple chunks

1. Heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke. Add the garlic and ginger and stir-fry for a few seconds, then add the sausages and cook on a medium heat for 3Ц4 minutes, stirring constantly. Remove from the heat and pour away the excess oil.

2. Return the wok to the heat, add the pepper and stir-fry for 1Ц2 minutes, then add the tomato and toss all the ingredients together. Add the cooked rice, breaking it up well, especially if it has been in the fridge overnight.

3. Season with the soy sauce, chilli oil and lemon juice, then mix in the pineapple chunks, remove from the heat and serve immediately. Delicious with a glass of cold lemonade.

CHINGТS TIP

If using freshly cooked rice, use 250g (9oz) of uncooked long-grain rice, such as basmati, rinse it well and then boil in 500ml (18fl oz) of water, cooking until all the water has been absorbed. This will take an extra 20 minutes.

Pork, ginger and duck egg congee

This is one of my favourite breakfast dishes. The famous cha chaan teng tea restaurants in Hong Kong serve it, especially the ones located in the old wet market at Canton Road in Kowloon. I love visiting the wet markets there; I usually go shopping early for ingredients and then reward myself with a steaming bowl of this congee.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

COOK IN: 65 minutes

SERVES: 4Ц6

2 century eggs, each sliced into quarters and halved lengthways

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

2.5cm (1in) piece of root ginger, peeled and finely sliced

200g (7oz) pork fillet, finely sliced

1 tbsp of Shaohsing rice wine, dry sherry or vegetable stock

3 shiitake mushrooms, finely diced

2 tbsps of light soy sauce

Salt and ground white pepper

Dash of toasted sesame oil (optional)

2 spring onions, finely sliced, to garnish

FOR THE CONGEE

250g (9oz) jasmine rice or 200g (7oz) jasmine rice and 50g (2oz) glutinous rice

250ml (9fl oz) vegetable stock

1. First make the congee. Pour the rice into a large heavy-based saucepan, add the stock and 700ml (1? pints) of water and bring to the boil. Once boiled, reduce the heat to medium-low, place a tight-fitting lid on the pan and allow to simmer, stirring occasionally to make sure the rice does not stick to the side and bottom of the pan.

2. After the rice has been cooking for 45 minutes, add the duck egg pieces and continue to cook for a further 20 minutes.

3. Meanwhile, heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke. Add the groundnut oil and ginger slices and stir-fry for a few seconds, then add the pork slices and stir for 1 minute or until they start to turn brown. Add the rice wine (or sherry or vegetable stock) and cook for a further minute, then tip in the mushrooms and season with the soy sauce.

4. Add the pork stir-fry to the cooked congee and stir in well. Season, add a dash of sesame oil, if you like, and sprinkle over the sliced spring onions. Serve immediately with chunks of you-tiao (fried bread sticks), if you have any, for a truly traditional Chinese breakfast.

Big bowl of oat congee and accompaniments Ц СThe WorksТ

This is not for the faint-hearted Ц like eating Сsmelly porridgeТ, as my other half describes it. But if you are a fan of durian, stinky dofu and century eggs, then you will love the complex flavours of this dish. The fermented bean curd blends in with the sweetness of the seaweed paste and picks up the fiery pungency of the pickled bamboo shoots, while the pickled lettuce delivers a refreshingly vinegary sweetness that cuts through the richness of all the other ingredients.

This dish brings back memories and instantly I am transported to my grandmotherТs farm, where daily breakfast treats would be a rotation of these ingredients, along with a small bowl of hot steaming congee (or rice porridge). Rice porridge takes too long for me to make in the morning, so I now have oat porridge instead. When I prepare this, assembling all the ingredients, it is like a meditation process and nostalgia trip rolled into one. Nothing can get in the way and I feel depressed when I run out of any of the components. You may be surprised and perhaps even disgusted by this strange obsession of mine, but I invite you to try the dish with courage and an open mind.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 6 minutes

SERVES: 1

100g (3?oz) rolled oats

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

2 eggs

5Ц6 chives or 1 spring onion, finely chopped (optional)

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

FOR THE ACCOMPANIMENTS

4Ц5 pickled soy lettuce stems

1 tsp of momoya (Japanese seaweed paste)

1 tbsp of salted roasted peanuts

1 tbsp of pickled bamboo shoots in chilli oil

2 tbsps of dried pork floss

? small cube of dofu (fermented bean curd)

1. Place the oats in a saucepan with 200ml (7fl oz) of water and bring to the boil, then reduce the heat and cook for 3Ц4 minutes, stirring frequently, or until the mixture has thickened.

2. Meanwhile, heat a small wok or frying pan over a medium heat until it starts to smoke and then add the groundnut oil. Crack in the eggs, sprinkle over the chopped chives or spring onion (if using) and fry the eggs to your liking.

3. Transfer to a plate and drizzle over the soy sauce. Pour the porridge into a bowl, arrange all your accompaniments on top (like the different colours on a painterТs palette) and then mix and eat straight away with the eggs.

Soups

Iadore Chinese soups Ц the classic takeaway offerings and the more exotic ones. The nourishing soups my grandmother used to make for me using Chinese herbs like cassia twigs, red dates, Angelica sinensis, rhizome of rehmannia and others that I cannot pronounce were a staple in my family kitchen. Both my mother and grandmother insisted that we have these herbal broths, often cooked with a little meat, such as lao-ji (old organic chicken) or pai-gu (pork ribs). This was based on the belief that these traditional Chinese herbs replenish the СyangТ chi (energy) thought to be good for a womanТs СsystemТ, keeping her fertile and youthful. My grandmother especially loved stewing these herbal concoctions and the meat she typically included would be pigТs trotters or chickenТs feet, believing that their gelatinous texture would help keep skin plump and beautiful Ц and I believe her, because grandmothers always know best. I never argued with my grandmother when it came to food; she was the food royalty in my family, the queen bee, and her opinion was always the final word on the subject.

I grew up not turning my nose up at such dishes because this was the norm in my family. I only realised that these treasured family recipes were СdifferentТ when my school friend Lina came over for dinner one Saturday night. I had recently moved from South Africa to London and had just started secondary school. Lina, of Lebanese origin, was the bubbliest girl at school and one of the most popular, so I was excited that she was coming round. My mother went to a Chinese supermarket and brought back the freshest ingredients. When asked what we were having for dinner, my mother pointed to a shiny red bucket with a bamboo steamer lid over it. We both took a peek and, to LinaТs horror, were greeted by two fat river eels writhing about in the water and staring up at us. My mum was planning to cook her herbal eel soup for us. I will never forget the look on LinaТs face! Needless to say, she didnТt stay for dinner and didnТt come round again for a very long time, let alone for dinner. When she eventually invited me to her house, I was greatly relieved that the Сeel experienceТ had not damaged our friendship.

Her family were so welcoming. It was a treat to watch her mother make houmous from scratch, her tete (grandmother) make the flatbread and tabouleh, and her father orchestrate the cooking of shish taouk and lamb shawarmas on their gigantic home-built barbecue. Everything smelt wonderful. We all sat around a large table and feasted together. Her father, a proud, eccentric man, made sure I had plenty to eat and my plate stayed full. I was enjoying everything until he winked at me to try a dish of what looked like very small sausages Е so I did. The whole room exploded in laughter; her brother patted me on my back and declared, СHow were the sheepТs testicles, Ching?!Т Wide-eyed, I turned to look at him and nearly spat the piece of СsausageТ in his face. So Lina and I were quits, and neither episode was ever mentioned again.

Lina and I continued to have many more culinary adventures together as our friendship developed. I once tried making her and some other schoolfriends chicken and sweetcorn soup, which was far too watery because it was the first large-batch cooking I had ever attempted. When we reached sixth form, sometimes we had no classes after lunch, so we would hitch the 240 bus from Mill Hill to Golders Green in search of satisfying our cravings for wonton soup or beef and black bean soup with ho fun noodles. Our destination was the Water Margin in Golders Green, where we would gossip about school or pour our hearts out over boys we fancied while sipping from a bowl of crabmeat and sweetcorn soup or hot and sour soup, dishes that comforted us and seemed to echo the sour-sweet times as teenagers living in London and trying to fit in. We fought to fit in at school, struggling with our cultural differences and desperate to find our identity, but food connected us.

My motherТs herbal eel soup may have tested my friendship with Lina, but it will always remind me of who I am and where I come from. I believe the strongest relationships are built on such experiences. I once overheard my mother on the phone to her friend; they were talking about a lady within the Chinese community whose English husband was apparently filing for divorce because he had caught her eating fish-head soup! The lesson I learned was that if those close to you accept your food choices, no matter how weird, they are true friends. In case you want to test this out yourself, I have included MumТs Herbal Eel Soup (see Soups) for you to try.

One thing is for sure, when IТm feeling under the weather, when there are dramas going on or IТm plagued by worry, I always make a comforting bowl of soup and I get my perspective back again. I have included some of my takeaway favourites here and given some a makeover.

Tomato and egg flower soup

Classic egg flower or egg drop soup (dan hua tang) Ц Сegg flowerТ describing the web-like pattern made by the egg when dropped into the hot liquid Ц is easy to make and very nutritious. You can add other ingredients to this soup, such as cubes of fresh dofu, baby prawns or dried seaweed (nori), or, for a more substantial dish, cooked egg noodles for a quick, light supper.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 10 minutes

SERVES: 2

1 tbsp of vegetable bouillon powder or stock powder

3 ripe tomatoes, sliced (see the tip below)

2 eggs, lightly beaten

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

Dash of toasted sesame oil

Pinch of sea salt

Pinch of ground white pepper

1 tbsp of cornflour mixed with 2 tbsps of water

Large handful of baby spinach (optional)

2 spring onions, finely sliced, to garnish

1. Pour 500ml (18fl oz) of water into a large saucepan and bring to the boil. Add the bouillon or stock powder and stir to dissolve. Reduce the heat to a simmer, then add the tomatoes and cook on a medium heat for 5 minutes or until the tomatoes have softened.

2. Pour the beaten eggs into the broth, stirring gently. Add the soy sauce, toasted sesame oil, salt, pepper and cornflour paste and mix well until slightly thickened. Add the spinach (if using) and let it wilt, then garnish with the spring onions and serve immediately.

CHINGТS TIP

I donТt bother skinning tomatoes Ц most of the nutrients are just beneath the skin after all Ц but if you want to skin them before slicing first cut a small cross at the base of each tomato. Plunge them into a wok or saucepan of boiling water for less than 1 minute, then drain. The skin will peel off easily.

Traditional hot and sour soup

This is one of my all-time favourite soup recipes. It transforms store-cupboard staples into an amazing dish. There may seem to be a long list of ingredients, but the end result is worth it because they all help to create layers of flavour and texture in this wonderfully warming winter dish.

PREP TIME: 20 minutes

COOK IN: 20 minutes

SERVES: 4

1 tbsp of vegetable bouillon powder or stock powder

1 tbsp of peeled and grated root ginger

2 red chillies, deseeded and finely chopped

300g (11oz) cooked chicken breast, shredded

1 tsp of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

2 tbsps of dark soy sauce

1 x 220g tin of bamboo shoots, drained

10g (

/

oz) dried Chinese wood ear mushrooms, soaked in hot water for 20 minutes, drained and finely sliced

100g (3?oz) fresh firm dofu, cut into 1 x 5cm (? x 2in) strips

50g (2oz) Sichuan preserved vegetables, rinsed and sliced (optional)

2 tbsps of light soy sauce

3 tbsps of Chinkiang black rice vinegar or balsamic vinegar

1 tbsp of chilli oil

Few pinches of white pepper

1 egg, lightly beaten

1 tbsp of cornflour mixed with 2 tbsps of water

1 large spring onion, sliced

Handful of chopped coriander, to garnish (optional)

1. Pour 1 litre (134 pints) of water into a large saucepan and bring to the boil. Add the bouillon or stock powder and stir to dissolve. Bring back up to the boil and then add all the ingredients up to and including the wood ear mushrooms. Reduce the heat to medium, then add the dofu, Sichuan vegetables (if using), soy sauce, vinegar, chilli oil and white pepper and simmer for 10 minutes.

2. Stir in the egg, then add the cornflour paste and stir to thicken the soup (adding more cornflour paste if you like a thicker consistency). Add the spring onion, garnish with the coriander, if you like, and serve immediately.

CHINGТS TIP

If you love your spicy heat, just increase the amount of chillies.

ALSO TRY

You can substitute the chicken with shiitake mushrooms for a vegetarian version of this dish.

Watercress soup with pork, mushroom and ginger wontons

Probably one of the most popular takeaway soups, this is also a personal favourite. I love these dumplings in a clear broth. The ones we used to have at the Water Margin were large and plump with a prawn and pork filling. This is my version; I like making mine small using small wonton egg wrappers, which you can easily pick up from a Chinese supermarket. The beauty of this dish is that you can serve it for a casual dinner or an elegant supper Ц versatile, like a pair of trusted black patent Fendi boots.

PREP TIME: 20 minutes

COOK IN: 10 minutes

SERVES: 4

28 wonton wrappers (7.5cm/3in square)

1 egg, beaten

700ml (1? pints) vegetable stock

FOR THE FILLING

250g (9oz) minced pork

1 large spring onion, finely chopped

3 shiitake mushrooms, finely diced

1 tbsp of peeled and grated root ginger

1 tbsp of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

1 tbsp of cornflour

Pinch of sea salt

Pinch of ground white pepper

TO SERVE

1Ц2 tbsps of toasted sesame oil

Small handful of watercress leaves

1 spring onion, finely sliced

1. Place all the ingredients for the filling in a large bowl and mix together well.

2. To prevent the wrappers from opening up once cooked, brush the inside of each one with some of the beaten egg. Take one wonton wrapper and place a small tsp of the filling in the centre. Gather up the sides of the wrapper and mould around the filling into a ball shape, twisting the top to secure it. Repeat with the remaining wrappers.

3. To make the soup, pour the stock into a large saucepan and bring to a simmer. Add the wonton dumplings and cook for 5 minutes or until they all rise to the surface Ц like floating clouds, as the Chinese might say.

4. Pour the soup and dumplings into serving bowls, allowing 7 dumplings per person. Add a dash of toasted sesame oil to each bowl, scatter over a few of the watercress leaves (letting them wilt in the bowl), finish with a sprinkling of sliced spring onions and serve immediately.

CHINGТS TIP

If any filling is left over, make more dumplings and freeze. They can be cooked from frozen for an emergency supper.

Pork rib, turnip and carrot broth with coriander

This is one of my grandfatherТs favourite recipes. It is not standard takeaway fare, but there are many takeaway and eat-in restaurants in Taiwan that serve this kind of pork rib soup (pai-gu tang) to accompany salty main dishes. Eaten between mouthfuls of the main dish, it works as a palate cleanser. It is a light sweet broth, the daikon (white radish) adding a slight bittersweetness to complement the meatiness of the pork ribs. When I eat it, it always reminds me of my grandmotherТs home cooking. If I had my own takeaway, this soup would be on the menu, no question.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

COOK IN: 25 minutes

SERVES: 4

250g (9oz) pork ribs, cut into 2.5cm (1in) pieces

2 tbsps of vegetable bouillon powder or stock powder

350g (12oz) daikon (white radish), sliced into 1cm (?in) rounds, each cut into 6 wedges

2 carrots, cut into 1cm (?in) rounds, each quartered into wedges

1 tbsp Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

Sea salt and ground white pepper

Handful of roughly chopped coriander

1. Prepare the pork ribs by blanching them in boiling water for 2 minutes and then drain well. Bring 1 litre (134 pints) of water to the boil in a large saucepan and add the bouillon or stock powder, stirring it to dissolve.

2. Add the pork ribs, daikon, carrots and rice wine or dry sherry. Bring back up to the boil, then reduce the heat to medium-low and simmer for 20 minutes or until the vegetables are tender. Season with salt and ground white pepper, add the chopped coriander and serve immediately.

Posh crab and crayfish tail sweetcorn soup

To me, a good takeaway would serve this soup. It may be relatively expensive, but it is so worth it. I usually have a few tins of crabmeat and sweetcorn in my store cupboard and this makes a delicious quick, light supper. If you are entertaining, you can jazz up this recipe by topping it with some cooked crayfish tails and serve with some toasted rye bread and butter. You could also substitute the tinned crabmeat with fresh crabmeat for a treat.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 15 minutes

SERVES: 4

2 x 170g tins of crabmeat in brine, drained

2 x 200g tins of sweetcorn, drained

1 large ripe tomato, sliced

2 eggs, beaten

3 tbsps of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of toasted sesame oil

Sea salt and ground white pepper

2 tbsps of cornflour mixed with 4 tbsps of water

1 large spring onion, finely sliced

180g (6?oz) cooked crayfish tails in brine, drained

1. Pour 1 litre (134 pints) of water into a large wok or saucepan and bring to the boil. Add the crabmeat, sweetcorn and tomato and bring back up to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 5 minutes.

2. Add the beaten eggs and stir gently to create a web-like pattern in the soup as the eggs start to cook. Season with the soy sauce, sesame oil and salt and pepper, adding more to taste if necessary. Bring to the boil and then stir in the cornflour paste to thicken the soup. Reduce the heat, sprinkle in the spring onion and leave to simmer on a gentle heat until ready to serve.

3. Ladle the soup into serving bowls, top with a few crayfish tails (which will warm through in the heat of the soup) and serve immediately.

ALSO TRY

You could substitute the crabmeat with cooked sliced chicken breast or, for a vegetarian option, use diced marinated dofu or sliced shiitake mushrooms (or chestnut mushrooms if you are on a budget). If you want a creamier consistency, use tins of creamed sweetcorn instead.

MumТs herbal eel soup

I wanted to include this more unusual recipe even though it doesnТt really have a connection to Chinese takeaways in the West. In Hong Kong, on the other hand, there are eateries that serve herbal soups such as this to take away. DonТt be put off by the sound of this soup Ц itТs actually quite delicious, although admittedly an acquired taste. You will either love or hate it Ц for me, itТs love. ItТs also very good for you. If you can, add a few dried goji berries to the soup 15 minutes before the cooking time is up; it lends a mellow sweetness to the broth. These, together with the other herbs, can be bought from a Chinese supermarket.

PREP TIME: 5 minutes

COOK IN: 65 minutes

SERVES: 4

600g (1lb 5oz) fresh river eel, head and tail discarded and any fins removed (or ask your fishmonger to do this for you)

2 tbsps of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

? tsp of salt

1 tbsp of vegetable bouillon powder or stock powder

5g (?oz) Angelica sinensis (Chinese angelica or dong quai)

5g (?oz) rhizome of rehmannia

8g (

/

oz) Ligusticum wallichii (Sichuan lovage)

5g (?oz) matrimony vine

5 dried red dates

2 x 5cm (2in) sticks of cassia

1 x 5cm (2in) stick of cinnamon

Small handful of dried goji berries (optional)

1. Slice the eel into 5cm (2in) pieces, keeping the bones intact, then rinse well. Place the pieces in a large saucepan of boiling water to blanch for 2 minutes and then drain and set aside.

2. Place the blanched eels back in the pan. Pour in 1.5 litres (2? pints) of water and add all the remaining ingredients except the goji berries. Bring to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 1 hour or until the eel is tender and delicious. If using the goji berries, add these for the final 15 minutes of cooking.

ALSO TRY

If youТre not so keen on the idea of cooking eel, then simply substitute it with chicken or pork ribs.

Appetisers

СNo, Peking duck is better.Т This is what my father would insist whenever he saw crispy aromatic duck on the menu at a Chinese restaurant. On one occasion I felt I had to intervene; I could see the disappointed look on the Swiss husband of one of my fatherТs guests. I told my father I had a craving for crispy duck and he called me a wai guo ren (foreigner) in front of his friends, at which everyone laughed, the Swiss man included. I couldnТt believe it! For the first time, I had put myself in the firing line to satisfy someone elseТs craving for a particular dish. On the plus side, I now occupied the moral high ground. I had been selfless in the sacrifice of my dignity for the happiness of another and thought my Buddhist master would be proud of my spiritual development (even if I was still a self-confessed carnivore).

Since my СenlighteningТ crispy duck experience, I was actually enlightened once again, years later, to find that crispy aromatic duck is basically Chinese in origin and not something just concocted for foreigners, bearing a resemblance to tea-smoked Sichuan duck, Cantonese roast duck and Peking duck. All four dishes use Chinese five spice, the difference being that crispy aromatic duck is deep-fried rather than oven-roasted. When I told my father this, he still maintained in his father-knows-best tone that Сcrispy duck is no good anyway because they fry the duck on its last days of freshnessТ.

Crispy aromatic duck seems to be confined to the UK. The debate continues about who invented it. According to the previous generation of Chinese food lovers, the Richmond Rendezvous Group Ц a chain of restaurants that created the boom in Chinese cuisine in the mid-1960s Ц was responsible for this delicious recipe that is consistently voted as the No. 1 Chinese takeaway dish in Britain.

Peking duck is equally popular: Beijingers see it as the national dish of China, the cr?me de la cr?me of all dishes. Chefs are super-proud of the delicious smoky golden skin of the duck and tender, succulent flesh, achieved by first slathering the bird in a maltose glaze and airdrying for eight hours before filling with water and cooking it in a wood-fired oven so that the meat is steamed on the inside while the outside remains crisp. At a good restaurant, the waiter will meticulously carve the skin and meat in front of you and serve the skin with some fine sugar. This will be served with thin steamed pancakes made from wheat flour, sliced cucumber, spring onions and a good tian mian jiang (sweet flour sauce). You should also expect a good restaurant to ask you how you would like the rest of the duck cooked Ц either in a delicious herbal broth soup or in a stir-fry with lush greens (I usually go with the chefТs recommendation). Both Peking duck and crispy duck are on my top list of favourite starters, so they are both included in this chapter, although my version of Peking duck is more like Cantonese roast duck because it is easier to recreate in the home kitchen.

I now have a tendency to judge dinner hosts based on their diplomacy when it comes to ordering (even if they are paying) and I am careful to be as sensitive as possible, to the point where I might be accused of being too nice. But better to be that, in my opinion, than greedy and selfish with no manners. There is a real art to ordering and being a good host; it takes real skill or gong-fu (kung fu). The Chinese are known for their generosity when it comes to dining, but a fine line needs to be trodden there as well: order too much and you look like a show-off; too little and you are seen as a scrooge. I take advice from my Buddhist master and that is: always finish what is on the table. It is better not to waste good food Ц think of all the people who go hungry.

When it comes to dinner parties at your own home, one thing is for sure: the very first dishes should impress. First impressions count. Like a teaser trailer to a blockbuster film, it should give you a hint of what to expect but without giving the whole plot away. It should excite and thrill you, satisfying you up to a point while leaving you hungry for more.

I usually serve a combination of СyangТ dishes, СyangТ being my label for СfriedТ because it doesnТt sound so bad. Yes, we all know that fried food comes with an СunhealthyТ tag, but it is all a matter of what you choose to eat. If you served and ate only fried food, you would soon be in A&E. Like everything in life, food choices are about balance. СYangТ is appropriate because, in food terms, it means СhotТ energy, i.e. food that creates more СheatТ within the body. The opposite of this is СyinТ or cooling energy. It is not good for the body to be too СyangТ, as it puts stress on the body. So my СyangТ menu carries this health warning Ц do not serve all these fried dishes in one meal; they are meant to be served only as an accompaniment to a variety of balanced dishes.

I have included many of my favourite naughty СyangТ takeaway starters (see Appetisers) such as Pork and Prawn Fried Wantons and Crispy Sweet Chilli Beef Pancakes, my take on crispy duck pancakes. If this is all too СyangТ for you, then fear not, as I have also included some СlengТ starters, i.e. СcoolingТ dishes that are more balanced and not fried (see Appetisers).

Vegetable spring rolls (chun juen)

Some may think this isnТt a traditional Chinese dish Ц but it is, usually eaten at the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year. It has northern Chinese roots where wheat flour is the main form of carbohydrate and bings Ц semi-rolled pancakes Ц are eaten, with various delicious fillings wrapped inside.

PREP TIME: 20 minutes, plus 10 minutes for cooling COOK IN: 7 minutes

MAKES: 12 small rolls

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

1 tsp of peeled and grated root ginger

100g (3?oz) shiitake mushrooms, sliced

100g (3?oz) tinned bamboo shoots, drained and cut into matchsticks

1? tbsps of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of Chinese five-spice powder

75g (3oz) bean sprouts

2 large spring onions, sliced lengthways

1 small carrot, cut into matchsticks

1 tbsp of vegetarian oyster sauce

Pinch of sea salt

Pinch of ground white pepper

24 small spring roll wrappers (14.5cm/6in square)

1 tbsp of cornflour mixed with 1 tbsp of water

1. Heat a wok over a high heat until it starts to smoke and then add 1 tbsp of the groundnut oil. Add the ginger and stir-fry for a few seconds. Tip in the mushrooms and bamboo shoots and stir-fry for 1Ц2 minutes, then season with 1 tbsp of the soy sauce and the five-spice powder. Remove from the wok and set aside to cool for 10 minutes.

2. Put the bean sprouts, spring onions and carrot into a bowl, add the fried mushrooms and bamboo shoots and season with the oyster sauce, remaining soy sauce and the salt and pepper. Stir all the ingredients together to mix.

3. Take 2 spring roll wrappers and lay one on top of the other. (The extra layer will help prevent the skin from breaking.) Spoon 2 tbsps of filling into the centre of the top wrapper and brush each corner with the cornflour paste.

4. With the wrappers laid out in a diamond shape before you, bring the two side corners to meet in the middle, then bring the lower corner to the middle and roll the pastry with the filling towards the top corner. Tuck in the top edge and seal it with the cornflour paste. Continue in the same way until all the wrappers are filled.

5. Place a wok over a high heat and add the remaining groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface. Deep-fry the spring rolls for about 5 minutes or until golden brown, then remove with a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper. Serve with a dipping sauce, such as sweet chilli sauce, if you like.

CHINGТS TIP

For a healthier СbakedТ option, substitute the spring roll wrappers with 12.5cm (5in) squares of filo pastry. Brush one sheet with groundnut oil, cover with a second sheet and brush with oil again. Fill as in the recipe, then place on a baking tray and bake in the oven (preheated to 180∞C/350∞F/gas mark 4) for 20 minutes.

Crispy seaweed

This does not originate in China Ц it was invented by Chinese cooks in the West. It doesnТt actually contain seaweed but is made with pak choy leaves that are finely shredded and deep-fried. I like to season mine with salt and granulated sugar so that itТs sweet and salty. ItТs a great way to use up any pak choy you may have that is slightly past its best, and is also great as an appetiser or sprinkled as a garnish over crispy squid.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

COOK IN: 2 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

200g (7oz) pak choy leaves, stems removed

Sea salt and granulated sugar, for sprinkling

1 tsp of toasted white sesame seeds (see the tip below)

1. Place a wok over a high heat and pour in the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface.

2. Add half the pak choy leaves and deep-fry for a few seconds, then lift out using a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper. Deep-fry the remaining pak choy leaves and drain in the same way.

3. Season the СseaweedТ with salt and sugar to taste, then transfer to a serving dish, sprinkle over the toasted sesame seeds and serve immediately.

CHINGТS TIP

You can buy sesame seeds ready-toasted, but they taste much better if you toast them yourself. Simply add the raw seeds to a frying pan set over a medium heat and dry-fry, tossing occasionally, for 3Ц4 minutes or until they begin to brown and become fragrant. Keep a close eye on them, as they can quickly burn, and remove from the heat as soon as they are toasted.

ALSO TRY

For a non-vegetarian option, you could sprinkle over dried pork or fish floss instead of the toasted sesame seeds.

Sesame prawn toast

This dish is a takeaway classic. Instead of mincing the prawns, however, I keep them whole, wrapping them in brown toast and sesame seeds and then frying them until golden brown. They are delicious served with sweet chilli sauce.

PREP TIME: 15 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes

MAKES: 8 toasts

1 tsp of peeled and grated root ginger

1 large spring onion, finely chopped

1 egg, beaten

1 tbsp of cornflour

Dash of toasted sesame oil

Dash of light soy sauce

Salt and ground white pepper

8 tbsps of white sesame seeds, toasted (see the tip opposite)

4 slices of brown toast, halved and crusts removed

8 raw tiger prawns, shelled and deveined, tails left on

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

1. Combine the ginger, spring onion, beaten egg, cornflour, toasted sesame oil and soy sauce in a bowl and season with 2 pinches of salt and some white pepper. Place the sesame seeds in another bowl.

2. Dip a half piece of toast in the mixture and coat well. Then wrap the toast around a prawn and squeeze slightly so that the bread fully covers the prawn. Roll the wrapped prawn in sesame seeds and coat well. Repeat with the remaining prawns and pieces of toast.

3. Place a wok over a high heat, add the groundnut oil and heat to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface. Deep-fry the sesame prawn toasts for 4Ц5 minutes or until golden brown, then remove with a slotted spoon, drain on kitchen paper and serve immediately.

СStinkyТ-style aromatic dofu with kimchi

Stinky dofu is made by fermenting dofu in a pungent brine, which gives it a distinctive smell and flavour. Traditionally, the brine consists of fermented milk, dried prawns, mustard greens, bamboo shoots and Chinese herbs. It does smell strong, but it is extremely flavoursome. This dish is one of my favourite street-food snacks and I often have a craving for it. The dofu is deep-fried and served with sour cabbage and chilli sauce. This is my own version. I like to marinate dofu that has been already fried (and which you can buy in a Chinese supermarket) in garlic, mirin and five-spice powder, then deep-fry it and serve with some Korean-style kimchi and a good hot chilli sauce.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes, plus 1 hour for marinating COOK IN: 3 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

8 x 6cm (2?in) square pieces of deep-fried dofu

4 tbsps of potato flour or cornflour

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

FOR THE MARINADE

2 cloves of garlic, crushed and finely sliced

4 tbsps of mirin

1 tbsp of clear rice vinegar or cider vinegar

1 tsp of Chinese five-spice powder

TO GARNISH (OPTIONAL)

Pinch of medium chilli powder

Few sprigs of coriander

TO SERVE (IN SEPARATE DISHES)

3 tbsps of kimchi

2 tbsps of chilli bean sauce

2 tbsps of chilli sauce mixed with 2 tbsps of oyster sauce

2 tbsps of hot chilli sauce

1. Mix together all the ingredients for the marinade in a bowl and add the dofu pieces, then cover the bowl with cling film and leave to marinate for 1 hour. Lift the dofu pieces out of the marinade, giving them a good squeeze to remove any excess liquid, then dust with the potato flour or cornflour.

2. Place a wok over a high heat and add the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a piece of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface. Fry the dofu for 2Ц3 minutes or until golden and crisp on the outside, then drain on kitchen paper and cut into triangular wedges (each cut in half, diagonally, to give 16 triangles).

3. Transfer to a serving plate and dust with the chilli powder and sprinkle with the coriander if you like. Serve with the assortment of small dishes of kimchi, chilli bean sauce, chilli oyster sauce and hot chilli sauce.

Sichuan salt and pepper squid

Squid contains lots of nutrients, including zinc, manganese, copper, selenium and vitamin B12. When cooked well, it has a delicious soft, chewy texture. I was once fed squid sperm sacs stir-fried with egg and spring onions in a seafood restaurant in Hong Kong and it certainly was an acquired taste! Squid itself is not so challenging, however, and salt and pepper squid is one the most popular starters to be served in Chinese restaurants as well as appearing on some takeaway menus. This dish is easy to make and does not require much effort. I love the numbing heat from the Sichuan peppercorns: just dry-toast them in a pan and grind them well to ensure the maximum flavour.

PREP TIME: 15 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

1 egg, beaten

100g (3?oz) potato flour or cornflour

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

200g (7oz) squid, cleaned and sliced into rings

Salt

2 pinches of dried chilli flakes

1 tbsp of Sichuan peppercorns, toasted and ground (see the tip below)

Sprigs of coriander, to garnish

TO SERVE

Lemon wedges

Fruity Chilli Sauce (see Appetisers)

1. Mix the beaten egg with the potato flour or cornflour and 2 tbsps of water to make a batter.

2. Heat a large wok over a high heat and add the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface.

3. Dip the squid rings into the batter and carefully drop into the hot oil. Deep-fry for 4Ц5 minutes or until golden, then lift out using a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper. Season with a little salt, the dried chilli flakes and ground toasted Sichuan peppercorns, then serve with lemon wedges and the Fruity Chilli Sauce and garnish with coriander sprigs.

CHINGТS TIP

To toast the Sichuan peppercorns, heat a small wok or saucepan over a medium heat, then add the peppercorns and dry-toast for 1 minute or until fragrant. Transfer to a spice grinder or pestle and mortar and grind to a powder. Alternatively, place in a plastic bag and smash with a rolling pin.

Five-spice salted prawns with hot coriander sauce

This is my take on salt and pepper prawns: prawns coated in a starchy batter and deep-fried, then tossed in a spicy salt and served with a grapefruit and coriander dipping sauce. It also makes a sophisticated appetiser for serving with cocktails.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

1 egg, beaten

100g (3?oz) potato flour or cornflour

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

12 raw tiger prawns, shelled and deveined, tails left on

FOR THE GRAPEFRUIT AND CORIANDER SAUCE

1 tbsp of peeled and grated root ginger

1 green chilli, sliced

1 red chilli, sliced

2 tbsps of lemon juice

Juice of ? large pink grapefruit (СbitsТ included)

Handful of coriander leaves, finely chopped

FOR THE SPICE MIX

1 tsp of Chinese five-spice powder

1 tsp of sea salt

1 tsp of ground white pepper

1. Mix together all the ingredients for the sauce in a bowl and set aside. In a separate bowl, mix together the egg, potato flour or cornflour and 2 tbsps of water to make a batter. Set to one side.

2. Place a wok over a high heat, add the groundnut oil and heat to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface.

3. Dip each prawn in the batter and then lower into the oil, one at a time. Cook for 4Ц5 minutes or until the prawns turn golden and then remove from the oil with a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper. Mix together the ingredients for the spice mix and sprinkle over the cooked prawns, toss well and eat immediately, served with the coriander sauce.

Japanese-style crispy halibut with lemon sauce

If you enjoy ordering lemon chicken from your local takeaway, then you will like this dish. It rather resembles English-style fish fingers Ц without the lemon sauce, that is! I like to use a good white-fleshed fish; cod is overfished, hence IТve used halibut here, but pollack would do just as well. You could even use mackerel if you wished. I like using the Japanese panko breadcrumbs because they have been flavoured with honey and are extra crisp, but you could make your own breadcrumbs, of course, using a chunk of stale bread. The dipping sauce is easy to make too.

PREP TIME: 15 minutes

COOK IN: 5 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

200g (7oz) halibut fillet, cut into 1cm (?in) strips

Sea salt and ground white pepper

100g (3?oz) potato flour or cornflour

1 egg, beaten

150g (5oz) panko breadcrumbs

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

Dried chilli flakes (optional)

Lemon wedges, to garnish (optional)

FOR THE SAUCE

1 tbsp of peeled and grated root ginger

1 tbsp of light soy sauce

1 tbsp of runny honey

1 tbsp of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

100ml (3?fl oz) cold vegetable stock

50ml (2fl oz) lemon juice

1 tbsp of cornflour

1. Season the halibut pieces with salt and white pepper. Put the potato flour or cornflour, beaten egg and breadcrumbs in three separate bowls. Dip the halibut pieces into the potato flour or cornflour, then the egg and coat in the breadcrumbs.

2. Place a wok over a high heat and add all but 1 tbsp of the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a piece of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface. Fry the breaded halibut pieces in the oil for 3Ц4 minutes or until golden brown, then remove with a slotted spoon and drain on kitchen paper.

3. Meanwhile, make the sauce. Heat a small wok or saucepan over a medium heat and add the remaining 1 tbsp of groundnut oil. Add the ginger and fry for a few seconds, then add the remaining ingredients and bring to the boil. Cook for 1 minute or until the sauce has thickened, then remove from the heat.

4. When the fish is cooked, season with dried chilli flakes (if using), garnish with lemon wedges, if you like, and serve with the lemon dipping sauce.

Chinese-style soft-shell crabs

In Chinese cooking, crabs are served in a variety of ways, from steamed and braised as well as deep-fried. This is a popular dish, served in Chinese restaurants all over the world. ItТs also one of my favourite dishes.

Soft-shell crabs can be bought in the frozen sections of a Chinese supermarket. The most well-known variety is the blue crab from America. As the crabs grow, they moult their old shells and for a short period between May and July their new shell remains soft and delicate.

PREP TIME: 15 minutes, plus 20 minutes for marinating COOK IN: 4 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

4 frozen small soft-shell crabs, defrosted

2 eggs, beaten

200g (7oz) potato flour or cornflour

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

2 large pinches of sea salt

2 large pinches of ground black pepper

1 tsp of dried chilli flakes

FOR THE MARINADE

1 tbsp of groundnut oil

1 tbsp of peeled and grated root ginger

1 tsp of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

1 tsp of Chinese five-spice powder

? tsp of medium chilli powder

1 tbsp of clear rice vinegar or cider vinegar

TO GARNISH

2 spring onions, finely sliced

2 red chillies, deseeded (optional) and sliced

1. To prepare a crab, first cut away the face (this can taste bitter), slicing behind the eyes. Next, lift the flap on the underside of the crab and cut this off. Loosen the top СshellТ of the body and lift it up to reveal the gills (plume-like filaments also known as Сdead manТs fingersТ Ц there are eight on each side of the crabТs body). These are inedible and should be removed, along with any brown meat. Rinse the crab well and prepare the remaining crabs in the same way.

2. Mix together all the marinade ingredients in a bowl, then add the crabs, cover with cling film and leave to marinate for 20 minutes. In a separate bowl, mix together the eggs, potato flour or cornflour and 2 tbsps of water to make a batter.

3. Place a wok over a high heat and add the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface.

4. Remove the crabs from the marinade and drain. Dip the crabs in the batter and then gently lower into the hot oil using a slotted spoon. Deep-fry for 3Ц4 minutes or until golden and then remove and drain on kitchen paper. Season with the salt, pepper and chilli flakes, then garnish with the spring onions and red chillies and serve immediately.

Sweet and sour Wuxi ribs

This dish originates from Wuxi in Zhejiang province. As this borders the neighbouring Shanghai municipality, it means that the dish can be found in many Shanghai restaurants too. The traditional way of preparing the ribs is to braise them slowly in stock for an hour, then add the sauce.

PREP TIME: 15 minutes, plus 20 minutes for marinating COOK IN: 10 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

600g (1lb 5oz) pork ribs, chopped into 3Ц4cm (1?Ц1? inch) pieces

400ml (14fl oz) groundnut oil

Sea salt and ground white pepper

1 spring onion, finely sliced, to garnish

FOR THE MARINADE

2 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

2 tbsps of yellow bean sauce

1 tbsp of Shaohsing rice wine or dry sherry

FOR THE SWEET AND SOUR SAUCE

2 tbsps of light soy sauce

2 tbsps of Chinkiang black rice vinegar or balsamic vinegar

1 tbsp of soft light brown sugar

1 tbsp of runny honey

1. Put all the ingredients for the marinade into a large bowl and stir to combine. Add the pork ribs and turn to coat, then cover the bowl with cling film and leave to marinate for at least 20 minutes in the fridge.

2. Place a wok over a high heat and add the groundnut oil. Heat the oil to 180∞C (350∞F) or until a cube of bread dropped in turns golden brown in 15 seconds and floats to the surface. Using a slotted spoon, carefully add the ribs and shallow-fry for 4Ц5 minutes or until browned and cooked through. Lift the ribs out of the wok and drain on kitchen paper.

3. While the ribs are cooking, place all the ingredients for the sweet and sour sauce in a small bowl and stir to combine.

4. Drain the wok of oil and wipe it clean, then place back over a high heat. Add the ribs and sauce mixture to the wok and cook on a medium-to-low heat for 5Ц6 minutes or until the sauce has reduced to a sticky consistency. Season to taste with salt and pepper, garnish with the spring onion and serve immediately.

Crispy sweet chilli beef pancakes

This is just like crispy duck pancakes but using beef instead of duck. The beef is coated in batter and then fried until crispy. To make a quick and easy sweet sauce, I have used a mixture of light soy, orange juice and shop-bought sweet chilli sauce.

PREP TIME: 20 minutes

COOK IN: 10 minutes

SERVES: 2Ц4 to share

300g (11oz) beef sirloin, fat removed, very finely sliced

2 tbsps of cornflour

600ml (1 pint) groundnut oil

FOR THE FRUITY CHILLI SAUCE

2 tbsps of light soy sauce

2 tbsps of sweet chilli sauce

Juice of 1 small orange

TO SERVE

2 carrots, cut into matchsticks

? cucumber (unpeeled), cut into matchsticks

2 spring onions, finely sliced lengthways

12 small wheat-flour pancakes

ALSO TRY

If you like, you could turn this dish into crispy beef by adding fried beef pieces to the thickened sauce in the wok, tossing together and garnishing with orange zest.

онец ознакомительного фрагмента.

“екст предоставлен ќќќ ЂЋит–есї.

ѕрочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/ching-he-huang/ching-s-fast-food-110-quick-and-healthy-chinese-favourites/?lfrom=688855901) на Ћит–ес.

Ѕезопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне ћ“— или —в€зной, через PayPal, WebMoney, яндекс.ƒеньги, QIWI ошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным ¬ам способом.