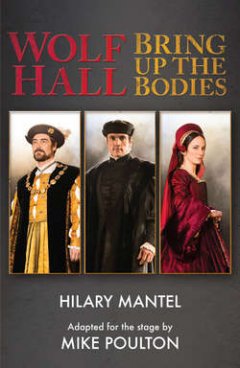

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: RSC Stage Adaptation - Revised Edition

Àâòîð:Mike Poulton

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:1291.34 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 419

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 1291.34 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: RSC Stage Adaptation - Revised Edition

Hilary Mantel

Mike Poulton

A new, revised edition for the London transfer of Mike Poulton’s expertly adapted two-part adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s hugely acclaimed novels, featuring a substantial set of character notes by Hilary Mantel.Mike Poulton’s ‘expertly adapted’ (Evening Standard) two-part adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s acclaimed novels ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring Up the Bodies’ is a gripping piece of narrative theatre … history made manifest’ (Guardian). The plays were premiered to great acclaim by the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon in 2013, before transferring to the Aldwych Theatre in London’s West End in May 2014.‘Wolf Hall’ begins in England in 1527. Henry has been King for almost twenty years and is desperate for a male heir; but Cardinal Wolsey is unable to deliver the divorce he craves. Yet for a man with the right talents this crisis could be an opportunity. Thomas Cromwell is a commoner who has risen in Wolsey’s household – and he will stop at nothing to secure the King’s desires and advance his own ambitions.In ‘Bring Up the Bodies’, the volatile Anne Boleyn is now Queen, her career seemingly entwined with that of Cromwell. But when the King begins to fall in love with self-effacing Jane Seymour, the ever-pragmatic Cromwell must negotiate within an increasingly perilous Court to satisfy Henry, defend the nation and, above all, to secure his own rise in the world.Hilary Mantel’s novels are the most formidable literary achievements of recent times, both recipients of the Man Booker Prize. This volume contains both plays and a substantial set of notes by Hilary Mantel on each of the principal characters, offering a unique insight into the adaptations and an invaluable resource to any theatre companies wishing to stage them.

WOLF HALL

and BRING UP THE BODIES

Adapted for the stage by

Mike Poulton

From the novels by

Hilary Mantel

With an introduction by Mike Poultonand character notes by Hilary Mantel

NICK HERN BOOKS

HarperCollinsPublishers

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk (http://www.nickhernbooks.co.uk)www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

Contents

Title Page (#u7ee4bb7c-06a8-5e12-982a-fc520e7d4305)

Original Production (#u9d1cdb33-21a2-5754-8598-2c48b05debe5)

Introduction by Mike Poulton (#u08f81d59-5f97-5a69-8766-9861fa1b89de)

Notes on Characters by Hilary Mantel (#u72485ca3-6afc-5399-aef3-03602b745147)

Characters (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#litres_trial_promo)

Wolf Hall (#litres_trial_promo)

Bring Up the Bodies (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Authors (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright and Performing Rights Information (#litres_trial_promo)

These adaptations of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies were originally commissioned by Playful Productions and were first produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, on 11 December 2013. The productions transferred to the Aldwych Theatre, London, on 1 May 2014, presented by Matthew Byam Shaw, Nia Janis and Nick Salmon for Playful Productions and the Royal Shakespeare Company, Bartner/Tulchin Productions and Georgia Gatti for Playful Productions. The cast was as follows:

Adapting Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies (#u67553341-2d31-5f29-98e6-778b3b6a3ff8)

Mike Poulton

Over three years ago I was asked if it might be possible to adapt Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall for the stage. At the time of asking, Bring Up the Bodies did not exist. I’d read Wolf Hall and been gripped by it – from the first page to the last – page 653. It’s an extraordinary read. To call it a historical novel diminishes it – for me it’s a deeply serious piece of literature that happens to be set in and around the Court of Henry VIII. I can think of no other contemporary work of period fiction that comes near it. It’s that rare thing – a novel that richly deserved its fame and the accolades and prizes heaped upon it. I knew that Hilary was at work on a sequel and I was counting the days. I read Wolf Hall again. I said that I thought it could be made into a play if the right adapter could be found. ‘Might you be the right adapter?’ I was asked.

I had never worked with a living author. Earlier collaborators, Schiller, Chekhov, Turgenev, Chaucer, Malory, were all long dead. Hilary is very much alive, and I knew that for the project to work she and I would have to get on together, and agree about how best to engineer the transformation. I imagined it would be like taking apart a Rolls-Royce and reassembling the parts as a light aircraft. After three years together I can say that our collaboration has proved to be, for me at any rate, the most rewarding part of the experience. I have learned so much. Hilary has been generous and committed in every way with advice, with time, with invention, with challenges – all coming out of a deep knowledge of her subject, and easy familiarity with the complex minds of the characters she has created. Fortunately, she also has a love and instinctive understanding of the workings of theatre. Above all it’s been fun – a lot of fun. Her attitude from the first was that she had brought Cromwell and company to life, and I was free, within the limits of the story and the requirements of historical accuracy, to move them about on the stage as I saw fit. Though on many occasions she has had to pull me out of holes into which I’ve dug myself. I’ve never had that sort of help from Friedrich von Schiller.

So what were the problems we faced at the outset? I felt that, in terms of staging – in order to create a workable dramatic framework – we had to get to the death of Anne Boleyn. If we could do that, we’d have a strong tragic arc – the ascendancy of Anne followed by her rapid decline. If Thomas Cromwell’s rise from obscurity was to be the story of the play, the Court of Henry VIII must be the stage upon which he acts, and the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn the engine that drives the action. I knew Hilary was working on a sequel to Wolf Hall, to be called The Mirror and the Light. Could she take me as far as Anne’s execution? Yes, of course she could. But by the time she reached the summer of 1536 we had another book, Bring Up the Bodies, and so much tempting new material that the original play was rapidly becoming two plays. Since that time the only heartbreak in the process has been deciding what to set aside.

Structurally, the new material was exactly what was needed. Wolf Hall would take us to Anne’s coronation, and Bring Up the Bodies to her execution. But the growing scale of the project and size of the cast meant that we needed a new partner and a new home. The Royal Shakespeare Company, under its brightly shining, new-minted Artistic Director, Gregory Doran, welcomed us in. This was a turning point. I’d worked five times with Greg, and I knew that from the RSC we’d get the expertise, support and resources the plays needed and deserved. We have not been disappointed.

It might be thought that the sheer length of the two books would present problems. I never thought so. The way a novel is structured cannot be reproduced on the stage – there could be no question of simply putting two whole novels on their feet. They had to be completely re-imagined as plays. The immediate questions were what would be lost, and what, if anything, would be gained in the stage versions? We set out to convert our difficulties into opportunities.

The content of the books cannot be condensed. You can’t repaint the jewel-like miniature scenes of the original with broad brushstrokes. You can’t ask an actor to play a summary of events – actors need detail. Adaptation is the process of choosing vital and dramatic details from the novels and relaying them like stepping stones along a clear route from a beginning, through a middle, and then in a headlong rush to the end. Pace is everything. To falter on stepping stones is to end up in the river.

Losses and gains? Strong characters are the life of Hilary’s books. So in terms of character, nothing could be changed. I wanted Cromwell, Wolsey, Anne and Henry – and all the other powerful characters we’ve included – to leap alive and fully formed from the pages of the books onto the stage of the Swan. If this could be accomplished, I felt the spirit of the book would remain intact. Incident has been lost. Obviously, we can’t reproduce every scene and every conversation we read in the original work, so we’ve had to be highly selective. There’s no doubt that readers will have favourite scenes that are not shown in the plays. But the story should gain a different sort of pace and drive in the playing. In the novels it’s as if we’re standing at Cromwell’s shoulder observing what he observes and sharing his thoughts. Seeing events through Cromwell’s eyes was the prime requirement of the adaptation. Sometimes what works perfectly in a novel won’t read in a live performance. Some of the most memorable images in the books are formed in Cromwell’s head: his reflections, his plotting, his private anguish, and, most of all, his barely contained laughter. Cromwell is very often on the point of dissolving into mirth. We decided at an early stage not to indulge in ‘pieces to camera’ – monologues delivered chorus-like by Cromwell to the audience. So in working with RSC actors through the drafts – there have been nine – we decided to give Cromwell two confidants, one from his household, one from Court, with whom he can share his thoughts: Rafe Sadler and Thomas Wyatt. And we have also provided him with a few completely new scenes which have no equivalent in the books.

Once the characters were comfortable, and sure-footed, on stage, it became possible to give them their heads in order to drive the plotting forward. There are many fewer characters in the plays than in the novels – a cast of one hundred and thirty would overcrowd the intimate playing space of the Swan – but other characters have risen to prominence and have been given more to do in the telling of the story. Christophe, for example, in some ways a model of Cromwell’s younger self, seems to be everywhere, and is usually up to mischief.

Our choice of theatre – the Swan is always my first choice – suggested, or rather insisted upon, a particular tone and style for our two plays. It’s a small space with a deep thrust stage. Wherever you sit, you feel you’re part of the action. Instead of looking over Cromwell’s shoulder, as in the books, throughout the plays you’re on stage with him. And he is on stage all the time. There’s spectacle – masques at Court, dances, courts of inquiry, even a coronation and a deer hunt. There’s detail – quiet scenes at home in Austin Friars, a fire in the Queen’s chambers in the middle of the night, scenes of intrigue and interrogation, and ghostly visitations. But there are no elaborate stage tricks – no revolves, lifts, nor clever-clever scene changes – everything has to be accomplished by the actors. They have their voices, their costumes, music, lighting, props, and an infinitely flexible playing space that can carry us in seconds from King Henry’s bedchamber, where he huddles for warmth over a fire, to a cold night on a boat in the middle of the River Thames. The Swan is the perfect theatre for storytelling. I’d previously worked through the twenty and more stories of The Canterbury Tales there, and there were valuable lessons to be learned from that experience. As I re-read Wolf Hall, and later Bring Up the Bodies, many more times, I tried to gear scenes to what I knew would work well in the Swan. And I knew – from touring Canterbury Tales – that if a play works in the Swan, it will play well in other theatres.

In bringing these two great novels to the stage, I have tried to replace the private pleasure of reading with the communal excitement of live theatre. When you read Wolf Hall, Cromwell and company get inside your head – they look as much through your eyes as you look through theirs. When you watch Wolf Hall, I hope we’re offering you a completely different experience – it should be like stepping into the world of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies – being rowed down the Thames with a dejected Wolsey, sitting at dinner with the King, chasing rats with Christophe, being in the Tower with Thomas More, or waiting to take a turn at swinging the headsman’s sword.

Notes on Characters (#u67553341-2d31-5f29-98e6-778b3b6a3ff8)

Hilary Mantel

Thomas Cromwell

Elizabeth Cromwell

Cardinal Archbishop Thomas Wolsey

King Henry VIII

Anne Boleyn

Katherine of Aragon

Princess Mary

Stephen Gardiner

William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury

Thomas Cranmer, Incoming Archbishop of Canterbury

Thomas More

Rafe Sadler

Harry Percy

Christophe

Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

Eustache Chapuys

Sir Henry Norris

Sir William Brereton

Mark Smeaton

George Boleyn, Lord Rochford

Francis Weston

Sir Thomas Boleyn

Thomas Wyatt

Gregory Cromwell

Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford

Mary Boleyn

Elizabeth, Lady Worcester

Mary Shelton

Sir John Seymour

Jane Seymour

Edward Seymour

Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower

The Calais Executioner

THOMAS CROMWELL

You are the man with the slow resting heartbeat, the calmest person in any room, the best man in a crisis. You are a robust, confident, centred man, and your confidence comes from the power you have in reserve: your Putney self, ready to be unleashed, like an invisible pit bull. No one knows where you have been, or who you know, or what you can do, and these areas of mystery, on which you cast no light, are the source of your power. When you are angry, which is rare, you are terrifying.

Your date of birth is unknown (nobody noticed) but you are in your forties during the action of these plays and about fifty at the time of Anne Boleyn’s fall. Your father was a blacksmith and brewer, the neighbour from Hell to the townsfolk of Putney, a heavy drinker and prone to violence. Your mother’s name is unknown. You don’t say much about your past, but you tell Thomas Cranmer, ‘I was a ruffian in my youth.’ Whatever this statement reveals or conceals, you have a lifelong sympathy with young men who have veered off-course.

At about the age of fifteen you vanish abroad. You join the French Army and speak French. You go into the household of a Florentine banker and speak Italian. You set up in the wool trade in Antwerp and speak Flemish and also Spanish, the language of the occupying power. You come home to London: and who are you? You’re a man who speaks the language of the occupying power. Traces of the blacksmith’s boy are almost invisible. The rough diamond is polished. You have seen at least one battle at close quarters, a calamitous defeat for your side; it’s enough to turn you against war. You have seen childhood poverty and modest prosperity and you know all about what money can buy. You have learned from every situation you have been in. You are flexible, pragmatic and shrewd, with a streak of sardonic humour. You are widely read, understand poetry and art. Somewhere on the road you found God. Your exact views (like much about you) remain unknown. But you are a reformer and your religious feelings are strong and genuine.

On the other hand… you’re quite prepared to torture someone, if reasons of State demand it and the King agrees. (You probably don’t torture Mark Smeaton.) You are a natural arbitrator and negotiator, preferring a settlement to a fight, but if pushed – as you are by the Boleyns in 1536 – you are ingenious and ruthless.

You marry Elizabeth Wykys, a prosperous widow with connection in the wool trade. You have three children. You take up the law and go to work for Cardinal Wolsey, looking after his business affairs. You help him raise the funds for Cardinal College (which is now Christchurch) by closing or amalgamating a group of small monasteries, work which equips you for the mighty programme of Church reorganisation you will soon undertake for Henry.

You and Wolsey are close. When he falls from favour, you are the only person who remains completely loyal. Much about you is equivocal, but this is not. You get yourself a seat in the Commons, and through his long winter in exile at Esher you attend every sitting, trying to talk out the charges that have been brought against him. You expend effort and your own money. When he goes north, you remain in London looking after his interests. You warn him that the way to survive is to retire into private life. But, though he listens to you on most matters, in this instance he doesn’t. His loss is devastating to you. Ten years later, you are still defending his good name: though Wolsey, a corrupt papist, ought to have been everything you hate.

You first come to Henry’s notice when Wolsey’s empire has to be pulled apart. Henry does not think he has many true friends and is touched by your loyalty to the Cardinal. You become his unofficial adviser long before you are sworn in to the Council. Your promotion causes predictable outrage, not just because of your humble background but because you are still known as the Cardinal’s man. To save everyone embarrassment, it is proposed you adopt a coat of arms from another, more respectable family called Cromwell. But you refuse. You are not ashamed of your background; you don’t talk about it, but you don’t conceal it either. In fact, you never apologise, and never explain. (And when you get your own coat of arms, you incorporate a motif from Wolsey’s arms, so that it flies in the faces of his old enemies for years to come.)

When your wife (and two little daughters) die, you do not marry again. This, for the time, is unusual. We don’t know your reasons. You have women friends; this is not understood, for example, by the Duke of Norfolk, who tells you that he never had a conversation with his own daughter until she was about twenty years of age, and was perplexed to find that she had ‘a good wit.’

Your household at Austin Friars, as you progress in the King’s service, is transformed, extended, rebuilt, into a great ministerial household, a power centre, cosmopolitan and full of young men who are there to gain promotion. You take on the people written off elsewhere, the wild boys who are on everybody’s wrong side, and make them into useful workers. You are an administrative genius, able to plan and accomplish in weeks what would take other people years. You are good at delegating and your instructions are so precise that it’s difficult to make a mistake. You extend the secretary’s role so that it covers most of the business of State; you know what happens in every department of Government. Your ideas are startlingly radical, but mostly they are beaten off by a conservative Parliament. At the centre of a vast network of patronage, you have a steady tendency to grow rich. You are generous with your money, a patron of artists, writers and scholars, and of your own troupe of actors, ‘Lord Cromwell’s Men’. The kitchen at Austin Friars feeds two hundred poor Londoners daily. All the same, you are a focus of resentment. The aristocracy don’t like you on principle, and the ordinary people don’t like you either. In the opinion of the era, there’s something unnatural about what you’ve achieved. In the north they think you’re a sorcerer.

Much of your myth is ill-founded. You do not control a vast spy network. You do not throw elderly monks into the road; in fact, you give them pensions. You are not the dour man of Holbein’s portrait but (witnesses say) lively, witty and eloquent. You have a remarkable memory, and are credited with knowing the entire New Testament by heart. Your particular distinction is this: you are a big-picture man who also sees and takes care of every detail.

Apart from your intellectual ability, your greatest asset is that you manage to get on with the most unlikely people. You are affable, gregarious, and amazingly plausible. You easily convince people you are on their side, when common sense should suggest different. You tie people to you by favours rather than by fear, and so they don’t easily see what a grip you’ve taken. People open their hearts to you. They tell you all sorts of things. But you tell them nothing.

What do you really think of Henry? No one knows. You don’t seem to feel the warmth towards him that Wolsey did, but you respect his abilities and you serve him because he is the focus of good order and keeps the country together. Dealing with him on a day-to-day basis needs tact and patience. You are optimistic and resilient, and believe there’s hope even for the bigoted and the terminally stubborn. Those who are on the inside track with you have their interests protected, and you take trouble to help out those in difficulties. But those who cross you are likely to find that you have been out by night and silently dug a deep pit beneath their career plans.

Your weakness is that you do not head up a faction or an interest group and have no power base of your own; you depend completely on the King’s favour. You are resented by the old nobility, and you are destroyed when your two implacable enemies, Norfolk and Gardiner, manage to make common cause. But by then, you have reshaped England, and even the reign of the furiously papist Mary can’t undo your work; you have given too many people a stake in your remodelled society.

ELIZABETH CROMWELL

You were the daughter of Henry Wykys, a prosperous wool trader, and were first married to Thomas Williams, a yeoman of the guard, and then to Cromwell. Your family were connected to Putney and may have been Welsh in origin. You have three children, Gregory, Anne and Grace. You die in one of the epidemics of ‘sweating sickness’ that sweep the country in the late 1520s, and your daughters follow you. You are a member of a close family and your sister, mother and brother-in-law continue to live at Austin Friars for many years.

We know nothing about you, so we can only say, ‘women like you’. City wives were usually literate, numerate and businesslike, used to managing a household and a family business in cooperation with their husbands. In Wolf Hall I make you a ‘silk woman’, with your own business, like the wife of Cromwell’s friend Stephen Vaughan, who supplied Anne Boleyn’s household with small but valuable articles made of silk braid: cauls for the hair, ties for garments. Cromwell watches you weave one of these braids, fingers moving so fast that he can’t follow the action. He asks you to slow down and show him how it’s done. You say that if you slowed down and stopped to think you wouldn’t be able to do it. He remembers this when he is deep into the coup against Anne Boleyn.

CARDINAL ARCHBISHOP THOMAS WOLSEY

You are, arguably, Europe’s greatest statesman and greatest fraud. You are also a kind man, tolerant and patient in an age when these qualities are not necessarily thought virtues.

You are not quite the enormous scarlet cardinal of the (posthumous) portrait. You are more splendid than stout, a man of iron constitution who has survived the ‘sweating sickness’ six times. You are a cultured Renaissance prince, as grand and worldly as any Italian cardinal. Renowned for the speed at which you travel, you are capable of an unbroken twelve-hour stint at your desk, ‘all which season my lord never rose once to piss, nor yet to eat any meat, but continually wrote his letters with his own hands…’ Your household observes you with awe, as does the known world. You hope you might be Pope one day, but think it would be more convenient if you could bring the papacy to Whitehall; you wouldn’t want to give up your palaces or your place next to your own monarch, and anyway you could probably run Christendom in your spare time.

You are the son of a prosperous butcher and grazier, and your family seem to have known how extraordinary you were, because they sent you to Oxford, where you took your first degree at fifteen and where you were known as ‘the boy bachelor’. The Church is the route to advancement for the poor boy. And your route is paved with gold. You acquire influential patrons and enter the service of Henry VII.

When Henry VIII came to the throne you were ready to take much of the burden off the young back, and the Prince was glad to let you carry it. You have real esteem and affection for the young Henry, and he loves you for your personal warmth as well as your unique abilities. You are not only Lord Chancellor but the Pope’s permanent legate in England. So your concentration of power, foreign and domestic, lay and clerical, is probably greater than that wielded by any individual in English history, kings and queens excepted. You are more than the King’s minister, you are the ‘alternative king’, ostentatious and very rich; suave, authoritative, calm; an ironist, worldly-wise, unencumbered by too much ideology. You never simply walk, you process: your life is a spectacle, a huge performance mounted for the benefit of courtiers and kings. You are acting, particularly, when you’re angry: after the performance, you shrug and laugh.

Until the point where this story starts, you have been able to solve almost every problem that’s faced you. You are so sure of yourself, that your unravelling is total and unexpected and tragic.

When Henry first asks for an annulment of his marriage, you are confident that you will be able to secure it. But the politics of Europe turn against you, and you find yourself trapped, faced with an impatient, angry monarch, and between two women who hate you: Katherine of Aragon, who has always been jealous of your influence with the King, and Anne Boleyn, who resents you because, before the King set his heart on her, you frustrated the good marriage she intended to make. You are astonished by the extent of the enmity you have aroused (or at least, you say you are) and, like everyone else, you are baffled by the King’s conduct; he wants you banished, then he offers to make peace, then he wants you banished.

For a year your enemies at Court are nervous that the King will reinstate you. No one is capable of assuming your role in Government, and Henry quickly learns this. When you are packed off to the north of England, you do not behave like a man in disgrace. You draw both the gentry and the ordinary people into your orbit, and soon you are living like a great prince again, and writing to the powers of Europe to ask them to help you regain your status. When these letters are intercepted, you are arrested and set out to London to face treason charges.

Soon after your arrest you have what sounds like a heart attack, followed by an intestinal crisis which leads to catastrophic bleeding. There are rumours that you have poisoned yourself. You are forced to continue the journey, and die at Leicester Abbey. Your body is shown to the town worthies so that no one can claim that you have survived and escaped, to set up opposition to Henry in Europe. It is the kind of precaution usually taken for a prince. Even dead, you spook your opponents. Your tomb – which you have been designing for twenty years, with the help of Florentine artists – is taken apart bit by bit and elements find their way all over Europe. At St Paul’s, Lord Nelson occupies your marble sarcophagus, rattling around like a dried pea.

KING HENRY VIII

Let’s think of you astrologically, because your contemporaries did. You are a native of Cancer the Crab and so never walk a straight line. You go sideways to your target, but when you have reached it your claws take a grip. You are both callous and vulnerable, hard-shelled and inwardly soft.

You are a charmer and you have been charming people since you were a baby, long before anyone knew you were going to be King. You were less than four years old when your father showed you off to the Londoners, perched alone on the saddle of a warhorse as you paraded through the streets.

Even as a child you behaved more like a king than your elder brother did. Arthur was dutiful and reserved, always with your father, whereas you were left with the women, a bonny, boisterous child, able to command attention. You were only ten when your brother married the Spanish Princess Katherine, but when you danced at the wedding, all eyes were on you.

At Arthur’s sudden death, your mother and father are plunged into deep grief and dynastic panic. It’s by no means sure that, were your father also to die now, you would come to the throne as the second Tudor; no one wants rule by a child. But your father battles on for a few more years, and you step into Arthur’s role gladly, an understudy who will play the part much better than the original cast member. Later, do you feel some guilt about this?

You are eighteen when you become King, a ‘virtuous prince’, seemingly a model for kingship; you are intellectually gifted, pious, a linguist, a brilliant sportsman, able to write a love song or compose a mass. Almost at once, you marry your brother’s widow and you execute your father’s closest advisers. The latter action is a naked bid for popularity, and it ought to give warning of the seriousness of your intent. Still, early in your reign you put more effort into hunting and jousting than to governing, with a bit of light warfare thrown in. You prefer to look like a king than be a king, which is why you let Thomas Wolsey run the country for you.

You are sexually inexperienced and will always be sexually shy; you don’t like dirty jokes. You have a few liaisons, but they are low-key and discreet. You never embarrass Katherine, who is too grand to display any jealousy, though she is too much in love with you not to care. However, you cosset and promote your illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy (a son you can acknowledge, as his mother was unmarried). Fitzroy has his own household, so is not part of the daily life of the Court, but is loaded with honours.

You are approaching forty when this story starts, five years younger than Thomas Cromwell. You are not ageing particularly well; still trim, still good-looking, you remain a superb athlete and jouster, but in an effort to hang on to your youth you have taken to collecting friends who are a generation younger than you, lively young courtiers like Francis Weston.

Your manner is relaxed, rather than domineering. You are highly intelligent, quick to grasp the possibilities of any situation. You expect to get your own way, not just because you are a king but because you are that sort of man. When you are thwarted, your charm vanishes. You are capable of a carpet-chewing rage, which throws people because it is so unexpected, and because you will turn on the people closest to you. But most of the time you like to be liked; you have no fear of confronting men, though you don’t seek confrontation, but you will not confront a woman, so you are run ragged between Katherine and Anne, trying to placate one and please the other. Unlike most men of your era, you truly believe in romantic love (though, of course, not in monogamy). It is an ideal for you. You were in love with Katherine when you married her and when you fall in love with Anne Boleyn you feel you must shape your life around her. Likewise, when Jane Seymour comes along…

When you ask Katherine for an annulment, you are not (in the view of your advisers) asking for anything outrageous. The Pope is usually keen to please royalty, and there are recent precedents in both your families. The timing is what’s wrong; the troops of Katherine’s nephew the Emperor march into Rome and the Pope is no longer free to decide. You are outraged when Katherine resists you and Wolsey fails you. You believe in your own case; you are a keen amateur theologian, and you think you know what God wants.

You are highly emotional. You are religious, superstitious, vulnerable to panic. Because you are so afraid of dying without an heir you’ve become a hypochondriac, and gradually a sort of self-pity has corrupted your character. You are so different from Cromwell that there’s probably little natural sympathy between you; you get your brotherly love from Archbishop Cranmer. But you need Cromwell as a stabilising force. You can carry on being loved by your people, as long as he will carry your sins for you. He begins by amusing and impressing you, proceeds by making you rich, and ends by frightening you. When, in 1540, you are told by Cromwell’s enemies that he intends to turn you out and become King himself, you completely believe it. For a few weeks, anyway. Then, as soon as his head is off, you want him back. It’s the Wolsey story over again. Who is to blame? Definitely not you.

ANNE BOLEYN

You do not have six fingers. The extra digit is added long after your death by Jesuit propaganda. But in your lifetime you are the focus of every lurid story that the imagination of Europe can dream up. From the moment you enter public consciousness, you carry the projections of everyone who is afraid of sex or ashamed of it. You will never be loved by the English people, who want a proper, royal Queen like Katherine, and who don’t like change of any sort. Does that matter? Not really. What Henry’s inner circle thinks of you matters far more. But do you realise this? Reputation management is not your strong point. Charm only thinly disguises your will to win.

You are the most sophisticated woman at Henry’s Court, with polished manners and just the suggestion of a French accent. Unlike your sister Mary, you have kept your name clean. You are elegant, reserved, self-controlled, cerebral, calculating and astute. But you are (especially as the story progresses) inclined to frayed nerves and shaking hands. You are quick-tempered and, like anyone under pressure, you can be highly irrational. You look at people to see what use can be got out of them, and you immediately see the use of Thomas Cromwell.

You come to the English Court in your early twenties, but you are in your late twenties before you catch Henry’s attention, and ours in the plays. Your contemporaries did not think you were pretty because they admired pink-and-white blonde beauty, and you (judging by their descriptions) were dark and slender. This difference becomes part of your distinction. It’s your vitality that draws the eye. You sing beautifully and dance whenever you can. You are the leader of fashion at the Court, before you become Queen.

When you are first at Court you become involved with Harry Percy, the heir to the Earldom of Northumberland. In the strictly regulated hierarchy of Court marriages, he is ‘above’ you, and is already promised to the daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury. Cardinal Wolsey steps in and makes Harry Percy go ahead with the Shrewsbury marriage. It’s at this point, your detractors will say, that you start to hate Wolsey and look for revenge. As far as the Cardinal is concerned, it’s nothing personal. But it wouldn’t be surprising if you took it personally. Harry Percy will later claim you had made a promise of marriage before witnesses, which would count as binding. At the time you are silent about the business. Whether you had feelings for Harry Percy, or were acting out of ambition, is not clear.

When the King makes his first approaches you are wary because you don’t intend to be a discarded mistress, like your sister Mary. You make him keep his distance and work hard for a smile. To think that you, a knight’s daughter, could replace the Queen of England is an idea so audacious that it takes a while for the rest of Europe to catch up with it. It’s assumed that, once Henry’s divorce comes through, he will marry a French princess. You are Wolsey’s downfall; for a long time, though he remembers you exist, he doesn’t know you’re important to the King. As far as he is concerned, he has finished his dealings with you when he makes Harry Percy reject you. There was a time when the King told Wolsey everything. But since you came along, that age has passed.

Your campaign to be Queen is fought with patience and cunning. Saying ‘no’ to Henry is a profitable business and you are made Marquise of Pembroke. There is a point when, after you feel Henry has committed himself to you, you’d probably be willing to go to bed with him; but by that time, he’s intent on remaining apart until you are married. He says you have promised him a son, and he wants to be right with his conscience and with God. Any child you have must be born within your marriage. You marry secretly in Calais, at the end of 1532, and a few weeks later, with no fuss, on English soil. Elizabeth is born the September following. Though Henry is disappointed not to have a boy, he doesn’t (as myth suggests) turn against you. He is glad to have a healthy child after losing so many, and confident of a boy next time.

Are you really a religious woman, a convinced reformer? No one will ever know. It’s probable that you picked up your ideas at the French Court, where the intellectual as well as the moral climate is freer. There’s nothing to gain for you in being a faithful daughter of Rome. The texts you put Henry’s way are self-serving, in that they suggest the subject should be obedient to the secular ruler, not to the Pope. But you go to some trouble to protect and promote evangelicals. ‘My bishops’, as you call them, are your war leaders against the old order.

Your family – your father, Thomas Boleyn, and your uncle the Duke of Norfolk – expect that, if they back you as Henry’s second wife, it will be to the family’s advantage, and they will be your advisers and indeed controllers. They are shocked to find that, once Queen, you consider yourself the head of the family. They begin to distance themselves from you as you ‘fail’ Henry by not providing a son, but your brother George is close to you and always loyal. Your sister Mary has a shrewd idea of what is going on; after the first blaze of triumph, you are unhappy.

You expected to be Henry’s confidante and adviser, as Katherine was in the early days of the first marriage. But Henry is less open now, and his problems (many of them caused by your marriage) are new and seem intractable. Gradually you realise that Cromwell, whom you regarded as your servant, is accreting more and more power and that he has his own agenda and his own interests.

Meanwhile, you are locked into an unwinnable contest with Henry’s teenage daughter Mary. She will never acknowledge you as Queen, even after her mother is dead. From time to time your temper makes you threaten her. No one knows whether you mean your threats, but it’s widely believed you would harm her if you could.

After Elizabeth’s birth you miscarry at least one, maybe two children. Henry feels he has staked everything on a marriage that, despite his best efforts, no one in Europe recognises. You start to quarrel. Ambassador Chapuys gleefully retails each public row in dispatches. Cromwell warns the Ambassador not to make too much of it; you have always quarrelled and made up. But, unlike Katherine, you don’t take it quietly when Henry looks at other women. That he would become interested in someone as mousy as Jane Seymour seems like an insult.

Besides, you are bored. You were always cooler than the King and perhaps irritated by his adoration. He is not a good lover. You collect around you a group of admiring men who are good for your ego. You don’t see the danger in what becomes an explosive situation. Or perhaps you do see it, but still you crave the excitement.

Meanwhile, nothing good is happening to your looks. Ambassador Chapuys describes you as ‘a thin old woman’ at thirty-five. There is only one attested contemporary portrait, a medallion, not a picture. In it you can clearly see a swelling in your throat, which was noticed by your contemporaries, who also called you ‘a goggle-eyed whore’. To our mind, this suggests a hyperthyroid condition. You are nervous and jittery, outside and inside. There’s something feverish and desperate about your energy. You can’t control it and you are wearing yourself out.

At some point on the summer progress of 1535 you become pregnant again. At the end of January, on the day of Katherine’s funeral, you lose the child, a boy. (Contrary to the myth that’s taken hold, there is no evidence that the child was abnormal.) In the opinion of Ambassador Chapuys: ‘She has miscarried of her saviour.’ You celebrated when you heard of Katherine’s death, but it is not really good news for you. In the eyes of Catholic Europe, the King is now a widower, and free.

You are now in trouble. You are right in thinking you are surrounded by enemies. Nothing you could do would ever reconcile the old nobility to your status, and the tactless and noisy rise of your family has cut across many established interests. Katherine’s old friends and supporters are beginning to conspire in corners, and make overtures to Cromwell. Will he support the restoration of the Princess Mary to the succession, if they back him in a coup against you?

When Henry decides he wants to be free, the idea is to nullify the marriage, not to kill you. The canon lawyers go into a huddle with Cromwell. Then the whole business is accelerated and becomes public, because in late April 1536 you quarrel with Henry Norris; and afterwards you visibly panic, giving the impression of a woman who has something to hide. Everything you say is keenly noted and carried to the King, who immediately concludes you have been unfaithful to him. Cromwell is talking to your ladies-in-waiting. It’s possible that, even at this stage, he is not sure how he will bring the matter to a crisis. But when you are arrested you break down and talk wildly, supplying yourself the material for the charges against you.

By the time of your trial and your death you have collected yourself and are, according to Cromwell, ‘brave as a lion’.

KATHERINE OF ARAGON

Thomas Cromwell: ‘If she had been a man, she would have been a greater hero than all the generals of antiquity.’

You are the daughter of two reigning monarchs, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. Your father was known for his political cunning and your mother for her unfeminine fighting spirit. When you are told that you have failed, because you have only given Henry a daughter, and a woman can’t reign, there must be a part of you that asks, ‘Why not?’ Another part of you understands; though you are highly educated, you are conventional and accept what your religion tells you: that women, after God, must obey men. This is a conflict that will run through your life.

You have known since you were a small child that you were destined for an English alliance, and even in your nursery you were addressed as ‘the Princess of Wales’. You are an object of prestige for the Tudors, who are a new and struggling dynasty with a weak claim to England. At fifteen you come to England to marry Prince Arthur. You are beautiful and much admired, tiny, fair-skinned, auburn-haired. You are sent to Ludlow to hold court as Prince and Princess of Wales. Within a few weeks, Arthur is dead. You will always say that your marriage was never consummated. Some of your contemporaries, and some historians, don’t believe you. Perhaps you are not above a strategic lie. Your parents would have told one and not blinked.

Now you enter a bleak period of widowhood. King Henry VII doesn’t want you to go back to Spain. You’re his prize, and he wants to keep your dowry. After he is widowed, he thinks of marrying you himself, a project your family firmly veto. You remain in London, without enough money, uncertain of your status, on the very fringe of the Court. Your salvation comes when Arthur’s seventeen-year-old brother succeeds to the throne. It’s like all the fairytales rolled into one. After a period of seven years, the handsome prince rescues you. He loves you madly. You adore him.

And you always will. Whatever happens, it’s not really Henry’s fault. It’s always someone else, someone misleading him, someone betraying him. It’s Wolsey, it’s Cromwell, it’s Anne Boleyn.

You look like an Englishwoman and, as Queen, an Englishwoman is what you set out to become. When Henry goes to France for a little war, he has such faith in you that he leaves you as Regent. All the same, the King’s advisers suspect your intentions. You act as an unofficial ambassador for your country, and are ruthless in pushing the interests of Spain, a great power which at this time also rules the Netherlands. Your nephew, Charles V of Spain, becomes Holy Roman Emperor, making him overlord to the German princes, in territories where new religious ideas are taking a hold. You are not responsive to these ideas. You come from a land where the Inquisition is flourishing, and though your parents have reformed Spain’s administration, they have done it in a way that consolidates royal power. Probably you never understand why Henry has to listen to Parliament, or why he might want popular support.

At first you are Henry’s great friend as well as his lover. Then politics sours the relationship; Henry and Wolsey have to move adroitly between the two great power blocs of France and Spain, making sure they never ally and crush English interests. And your babies die. There are six pregnancies at least, possibly several more; the Tudors didn’t announce royal pregnancies, still less miscarriages, if they could be hidden. They only announced the happy results: a live, healthy child. You have only one of these, your daughter Mary.

You are older than Henry by seven years. And the pregnancies take their toll on your body. You become a stout little person, but you are always magnificently dressed and bejewelled; a queen must act like a queen. You are watched for signs that your fertile years are over. When Henry decides he must marry again, the intrigues develop behind your back. You are not at first aware, and nor is anyone else, that Henry has a woman in mind and that woman is Anne Boleyn. You believe he wants to replace you with a French princess, for diplomatic advantage, and you blame Wolsey, who you have always seen as your enemy; for years he has been your rival for influence with the King. You think you understand Henry. But for years he’s been drifting away from you, the boy with his sunny nature becoming a more complex and unhappy man.

Once the divorce plan is out in the open, no notion of feminine obedience or meekness constrains you. You fight untiringly and with every weapon you can find, legal and moral. The King says that Scripture forbids marriage with a brother’s wife. You insist that you were never Prince Arthur’s wife, that you lay in bed together as two good children, saying your prayers. You also believe that even if you and Arthur had consummated your marriage, you are still legally married to Henry; the Pope’s dispensation covered both cases.

No settlement is in sight. You are offered the option of retiring to a convent; if you were to become a nun, your marriage would be annulled in canon law, and, given that you are deeply religious, Henry hopes that might suit you. But as far as you are concerned, your vocation is to be Queen of England, and that is the estate to which God has called you, and you and God will make no concessions. You are always dignified, but you will not negotiate and you will concede nothing.

You are sent to a series of country houses: not shabby or unhealthy, as the legend insists, but remote, well away from any seaports. You are separated from your daughter, which agonises you, because she is in frail health and also you fear that she will be pressured into accepting that she is illegitimate. Though you are provided with a household to fit your status, you live in virtual isolation because you will not answer to your new style of ‘Dowager Princess of Wales’ and insist on being addressed as Queen. Soon you have confined yourself to one room, and your trusted maids cook for you over the fire. Henry sends Norfolk and Suffolk to bully you, without result. Finally you are divorced in your absence. You die in January 1536, after an illness of several months’ duration, probably a cancer. The rumours are, of course, that Anne Boleyn has poisoned you.

Cromwell’s admiration for you is on the record: even though his life would have been made simpler if you had just vanished, he admired your sense of battle tactics and your stamina in fighting a war you could not win. His approach is pragmatic and rational; he’s not a hater. You understand this. You may think, as much of Catholic Europe does, that he is the Antichrist. But you write to him in Spanish, addressing him as your friend.

PRINCESS MARY

Born seven years into your parents’ marriage, you are the only surviving child. You are in your mid-teens when you appear in this story. You are small, plain, pious and fragile: very clever, very brave, very stubborn. You hate Anne Boleyn, and revere your father, following your mother’s line in believing that he is misled. When you are separated from Katherine, and kept under house arrest, you are physically ill and suffer emotional desolation. You believe when Anne is executed that all your troubles are over. You are stunned to find that your father still requires you to acknowledge your illegitimacy and to recognise him as Head of the Church. You resist to the point of danger. Thomas Cromwell talks you back from the brink. Your dazed, ambivalent relation with him begins in these plays.

STEPHEN GARDINER

Cambridge academic, Master of Trinity Hall, you are in your late thirties as this story begins, and secretary to Cardinal Wolsey, who admires your first-class mind, finds you extremely useful, and has little idea of the grievances you are accumulating. Tactless and bruisingly confrontational, you are physically and intellectually intimidating, and your subordinates and your peers are equally afraid of you. But you suspect Thomas Cromwell laughs at you, and you are possibly right. You can only stare with uncomprehending hostility as he talks his way into the highest favour with Wolsey first and then the King. Cromwell is at his ease in any situation. You are the opposite, constantly bristling and tense.

Your origins are a mystery. You are brought up by respectable but humble parents, who are possibly your foster-parents. The rumour is that you are of Tudor descent through an illegitimate line, and so you are the King’s cousin. This may be why you get on in life; or it may be you are valued for your intellect; your personality is always in your way, and you seem helpless to do anything about it.

As you are politically astute and unhampered by gratitude, you begin to distance yourself from the Cardinal some months before his fall, and become secretary to the King. You are promoted to the bishopric of Winchester, the richest diocese in England. You are conservative in your own religious beliefs, but you are an authoritarian and a loyalist who will always back Henry, so you work hard for the divorce from Katherine, and you are all in favour of the King’s supremacy in Church and State. But Henry finds your company wearing; you always want to have an argument. And he likes people who can read his mood and respond to it.

So once again the pattern repeats; you are pushed out of the King’s favour by Cromwell, and have to watch him grow the secretary’s post into the most important job in the country (after king). Cromwell is generally so plausible that even Norfolk sometimes forgets to hate him. But you never forget.

During the years of his supremacy, Cromwell will keep you abroad as much as possible, as an ambassador. When you finally make common cause with the Duke of Norfolk, his other great enemy, you will be able to destroy him.

Cromwell suspects, and he’s right, that underneath all, you are a papist, and that, given a chance, a swing of political fortune, you would take England straight back to Rome. This proves true; in the reign of Mary Tudor, you grab your chance, become Lord Chancellor and start burning heretics.

WILLIAM WARHAM, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY

You are over eighty years old and are a man of immense dignity, when awake. You have been Archbishop for almost thirty years. A former Lord Chancellor, you were pushed out of that role by Wolsey. Your favourite saying is, ‘The wrath of the King is death.’ So you do not oppose Henry’s divorce or the early stages of the Reformation, but at the very end of your life, as in your scene here, you find the unexpected courage to disagree with the King. So your rebuke carries weight.

THOMAS CRANMER, INCOMING ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY

You are the introvert to Cromwell’s extrovert. You act so much in concert that some less well-informed European politicians think you are one person: Dr Chramuel. When you and your other self are with Henry, you go smoothly into action, able to communicate everything to each other with a glance or a breath.

You are a reserved Cambridge don, leading a quiet life, when you chip in an idea about Henry’s divorce: why doesn’t he poll the European universities, to give his case some extra gravitas? The King likes this idea and soon you are at the heart of the struggle, a family chaplain to the Boleyns, guiding them, cautiously, towards reformed religion, and hoping to take Henry the same way. You must be wary of Cromwell, with his reputation as Wolsey’s bully boy. But once you begin to work together, you instinctively understand each other and become friends.

Intellectually rigorous, you are not the cold fish you may appear. As a young man, not yet a priest, you made an impulsive marriage. This meant you had to give up your fellowship at Jesus College, and try to find work as a clerk or tutor; your father is a gentleman, but you have no money from him, and Joan was just a servant when you met her. Within a year you lose your wife in childbirth. The child dies too. Jesus College takes you back. You are ordained. Perhaps nothing else will ever happen to you?

Your promotion to Archbishop is something you could never have imagined, even a year or two before it happened. Though you can appear cerebral and withdrawn, you are in tune with the emotions of others; you are a gentle person, who tends to calm situations. You are psychological balm to Henry and to Anne, both of them restless and irritable people. Henry loves you, and (as Cromwell said) you can get away with anything, including your increasingly Protestant convictions, and the second mad marriage you make. You fall in love when you are on mission in Germany, and smuggle your wife back. Henry is fiercely opposed to married clergy; he must know about Grete, but he closes his eyes.

You are possibly the only person in England without a bad word to say about Anne Boleyn. You are swept up in the terrifying process of her ruin, with hardly a chance to protest. You turn this way and that: how can these allegations be true? But if they were not true, would a man so good as Henry make them? You do believe in his goodness, which is what he needs. You go on trying to believe it, against all the accumulating evidence. In many ways as the years go on, your role as Archbishop becomes a torture to you. Though Henry makes many concessions to reform, he remains stuck in the Catholic mindset of his youth. You and Cromwell have to stand by while he persecutes ‘heretics’ who share your own beliefs. Henry thinks you are a hopeless politician, and likes you all the better for it. But you are wiser than he thinks. You never pointlessly antagonise him, but prudently and patiently salvage what you can from each little wreckage he makes.

When Cromwell falls, you will go as far to save him as your natural timidity allows. You will beg the King to think again, and ask him pointedly, ‘Who will Your Grace trust hereafter, if you cannot trust him?’ You are not naturally brave but you are wise, humane and sincere, and eventually in Mary’s reign you will die horribly for your beliefs.

THOMAS MORE

You would keep a tribe of Freudian analysts in business for life. They would hold conferences devoted just to you. An absent-minded professor with a sideline in torture, you turn on a sixpence, from threatening to cajoling to whimsicality. Ill-at-ease in your skin, self-hating, you show your inner confusion by your relationship with your clothes; you look as if you are wearing someone else’s, and got dressed in the dark. This disarrayed outside makes you seem vulnerable, even harmless; but inside, your barriers are rigid and your core is frozen.

You have a father to live up to: good old Sir John More, stalwart of the London law courts, a man with a fund of anecdotes that you will be telling for the rest of your life. You follow him into the law. You think you should become a monk, but you fail. You decide you can’t live without sex; and you don’t want to be a bad monk. Perhaps, also, you want the warmth of family life. You can’t do without people. You can’t detach, as a religious man should. The realisation causes you anguish. The inner conflict, the consciousness of sin, is so painful you have to flagellate yourself as a distraction. You wear a hair shirt. Not figuratively, literally.

Yet you are one of the showpieces of Henry’s Court: an intellectual, to vie with those good-quality ones they have abroad. You seem so modern, if we ignore the hair shirt. You are a scholar and a wit, a great communicator, a man attentive to your own legend; if you lived now, you would write a column for one of the weekend papers, all about the hilarious ups and downs of family life in Chelsea. You are a member of several Parliaments and serve as Speaker. You keep amicable relations with Wolsey while he is in power, but are ferocious at his fall. For all your urbanity, you are an excellent hater. When you write about Luther or other evangelicals, your detestation comes spilling out in an uncontrollable flood of scatological language. It’s as if you have a poisoned spring inside you. Unluckily, the times allow you to release your violence, instead of forcing you to suppress it. You have a busy legal practice but your real vocation is persecuting heretics.

Posterity will excuse you, saying, ‘It’s what they did; those were not tolerant times.’ But Cardinal Wolsey was loyal to Rome, and he managed his long tenure as Lord Chancellor without burning anybody. You preside over a handful of executions, but you damage the lives of many, imprisoning suspects until they are mortally ill or their businesses fail. You are not apologetic. You are proud of your record, and you want it mentioned in your epitaph, which, of course, you have written in advance.

You have been in Henry’s life since he was a boy, and he looks up to you, and you are confident that you can influence him for the better. So when he asks you to take over as Lord Chancellor, you agree, as long as you don’t have to work on his divorce. Within a short time your position becomes untenable, and it’s obvious that the King is listening to Cromwell, not you. Your path has crossed Cromwell’s many times. Your raid on his house, in these plays, is a convenient fiction, shorthand for the hostility between you, and modelled on your raids on Cromwell’s friends. Probably you wouldn’t care to confront him so directly, even after Wolsey’s protection is withdrawn. Besides, you don’t know where to place Cromwell; you’re never sure whose side he’s on. You suspect he might be solely motivated by money. You never imagine he’s a man of conviction. Perhaps your failing, as a political animal, is that you don’t give your opponents credit; you don’t believe they are as clever or determined as you are. You think the King is still a boy who can be led. Quite possibly, you think Cromwell is overconfident and will come unstuck. He doesn’t explain himself. Neither do you. You are a master of ambiguity and soon you need all your skills to keep you alive.

Henry permits you to retire into private life. You go home to Chelsea and live quietly. The country is seething with plots, but you keep your hands clean and you do not talk about your views. You refuse the invitation to Anne Boleyn’s coronation, which is a mistake. It suggests to Henry and Anne that you remain hostile to their marriage, though you’ve never made any public objection. When you are required to take an oath to recognise Henry as Head of the Church, and Anne’s daughter Elizabeth as heir, you refuse. But you won’t say why. So you sit in the Tower of London for a year, while your family and friends try to talk you into a compromise, and Cromwell negotiates. Sometimes he pushes you and sometimes he gives you, you say, the good advice you’d get from a friend. Perhaps Henry will forget you? But he won’t, because he’s furious that a man he admired has turned against him.

You are not ill-treated. There is no question of physical force, but there is intense mental pressure, and there is fear and loneliness. Finally, you entrap yourself, in conversation with Richard Riche, a young lawyer you despise; you knew he was Cromwell’s man, but you couldn’t resist chatting away, ‘putting cases’ as if you were still a student. Riche reports your ‘treason’ and Cromwell hauls you into court. It’s a failure on his part; victory would have been to break your spirit, and not to have the embarrassment of executing a famous opponent of the regime. You are not a martyr for freedom of conscience, as recent legend suggests. You are the old-fashioned kind of martyr, dying for your faith, or, as Cromwell sees it, for your belief that England should be ruled from Rome.

RAFE SADLER

You are twenty-one when this story begins, and as seasoned and steady as a man twice your age. You are brought up by Thomas Cromwell, but by the time you are in your late twenties you have become his father, and tell him off when you think he’s being frivolous. You are a quietly admirable character, and you manage to do something very difficult: you last the distance in politics, and keep your integrity.

Your own father is a gentleman and minor official, caught up in the great dragnet of Wolsey patronage. He somehow spots Cromwell as the man to watch, though at the time he is only a young London lawyer. You grow up in his increasingly lively household, as close as a son, and by the time of the Cardinal’s fall you are his chief clerk. Henry likes you, and in 1536 promotes you to a position in his own household, so you act as daily liaison for Cromwell. You are utterly loyal to him, hard-working, sober and shrewd. You’re cautious by nature, practical, steady, very able, and seldom put a foot wrong. Thankfully, you do one silly thing in your life: instead of marrying for career advantage or money, you marry a poor girl with whom you’ve fallen in love. Whoever else might see this as a problem, Cromwell doesn’t. He has your future in hand anyway.

You build yourself a shiny new country house at Hackney, the garden adjoining one of Cromwell’s properties. Later you acquire a country estate. You and Helen have a whole tribe of children, the eldest called Thomas. Though you can’t bear to be apart, you can never take Helen to Court, and you are mostly at Court as you are increasingly necessary to Henry. When, in 1539, Cromwell, staggering under the burden of work, finally parts with the post of Mr Secretary, the job is split between you and Thomas Wriothesley. At Cromwell’s fall, you cannot save him but you behave with dignity and courage. You carry his last letter to Henry. Read it, Henry says. You do so. Read it again. And a third time: read it. You can see the King has tears in his eyes. But he doesn’t speak; there’s no reprieve. It is you who carries Cromwell’s portrait from the wreck of Austin Friars, as his opponents loot it.

After Cromwell, you are beaten out of the top jobs by the unscrupulous Wriothesley, but make your name as an envoy to Scotland, a hardship posting which sometimes involves dodging musket balls. You are a little man, with no pretentions to military prowess, and no interest in sports other than hawking. But, at the age of forty, caught up in the Scots wars, you will ride into battle under Edward Seymour, and behave with such valour that you are knighted on the battlefield. Pent-up aggression, probably, from all those years of being discreet.

You serve three sovereigns (retiring from public life under Mary). You are a Privy Councillor for fifty years, and are still working for Elizabeth I at the age of eighty. You’re too precious to be let go; you know where the bodies are buried. The Cromwellian ability to make money has rubbed off, and you die the richest commoner in England.

HARRY PERCY, EARL OF NORTHUMBERLAND

You are in your early twenties when you first become involved with Anne Boleyn and in your mid-thirties when these plays end. You were brought up in Wolsey’s household and he had a poor opinion of your abilities. As the Earl of Northumberland’s heir, you contracted a mountain of debt, and when your father came to Court to tell you off about your involvement with Anne Boleyn, he called you ‘a very unthrift waster’. You seem to be a muddle-headed, emotional, unreliable young man, with poor judgement; not a man to dislike, not a cowardly man, but a confused one, frequently out of his depth.

Under protest, you give up Anne and contract the marriage arranged for you, with Mary Talbot, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury. Your only child with her does not survive and the marriage is miserable. When you inherit the earldom, you begin alienating land to pay your debts, prejudicing the holdings of your younger brothers. A complex of family quarrels and financial disasters adds to your unhappiness, though you are not frozen out by the King at this stage; your family name decrees that you should be made a Knight of the Garter, and the geography of your land holdings makes you important in defence against the Scots.

When you are sent to arrest Wolsey in Yorkshire, you are reported to be shaking with fear. He laughs at you and refuses to credit your authority, though he agrees to be taken into custody by the officials with you.

From about 1529 you are ill and convinced you will die early. Perhaps this makes you reckless. You refuse to live with your wife and, in the hope of obtaining her freedom, she tells her father that you have always claimed to be married to Anne Boleyn. Anne is on the point of marrying the King and insists on an investigation. Under pressure, you swear on the blessed sacrament that you never contracted a marriage with her. All the same, rumours persist.

In 1536 you are asked by Cromwell to retract your oath and say that you were, after all, married to Anne. This would give the King an easy and bloodless exit from his marriage. You refuse to do so. You are perhaps afraid of the consequences for your soul, and by now you resent and detest the Boleyns. (Chapuys has seen you as a candidate to join an aristocratic conspiracy against the King, but has been told you are ‘light’ and untrustworthy.)

You are one of the peers who sit in judgment at Anne’s trial. You concur in the guilty verdict and then collapse.

You die in 1537, your lands taken over by the Crown. There is no new Earl until 1557.

CHRISTOPHE

On one of Cardinal Wolsey’s State visits to France, he was systematically robbed of his gold plate by a small boy who went up and down the stairs unnoticed, passing the loot to a gang outside. In the world of Wolf Hall, you are the small boy. So you are a fiction, with a shadow-self in the historical record.

Thomas Cromwell is ignorant of your earlier life and previous names when he runs into you in Calais in 1532. You are the waiter in a backstreet inn, where he is entertaining a cabal of elderly and impoverished alchemists from whom he hopes to obtain a working model of the human soul. He has time to notice that you are a cheeky, dirty, violent little youth, who reminds him irresistibly of his younger self. Deciding he is a great milord, you follow him to his lodgings and announce you mean to ‘take service’ with him and see the world.

At Austin Friars you are an all-purpose dogsbody. With difficulty, you make yourself fit to be seen with a gentleman. You find good behaviour a great strain. The legacy of your former life is that you are always hungry.

THOMAS HOWARD, DUKE OF NORFOLK

‘I have never read the Scripture, nor will read it. It was merry in England before the new learning came up: yea, I would that all things were as hath been in times past.’

You are almost sixty when this story begins, with the vigour of a man half your age; you run on rage. Your grandfather was on the wrong side at the Battle of Bosworth, and your family lost the dukedom. Your father regained the favour of Henry VII, annihilated the Scots at the Battle of Flodden, and got the title back. And you expect a battle every day, and are always armed for one, visibly or not. You never forget what damage a king’s displeasure can do. To his face, you are creepingly servile to Henry Tudor. In private, you probably regard him as a parvenu, and a bit of a girly as well.

With the exception of Henry’s illegitimate son, you are England’s premier nobleman, an old-style magnate who holds a magnificent court in East Anglia. Your courtier’s veneer is paper-thin. You prefer warfare. But you are not without diplomatic weapons, as you will lie to anyone.

You hate Wolsey: in your view, he is common, greedy and pretentious. You are also frightened of him, as you think he has the power to put a curse on you. You are one of the main agents of his fall, and you threaten that if he does not make speed to the north, away from Court, ‘I will come where he is and tear him with my teeth.’ You are supremely valiant at kicking a man when he’s down.

You beat your wife, or at least she tells Cromwell that you do; she also complains that your in-house mistress knocked her down and sat on her. She tells Cromwell everything, and she sends him presents. Cromwell is everywhere you look, in your face, and once you accept it you approach him with a gruesomely false bonhomie, teeth gritted.

You back the efforts of your niece, Anne Boleyn, to become Queen, because you think it will be good for the family, but you turn against her when you realise that she has no intention of obeying her uncle. Presiding over her trial, you have no hesitation in sentencing her to death, and a few years later will do the same for another niece, Katherine Howard. Though you are innately conservative and papist, you say yes to anything Henry wants, and when Cromwell begins to dissolve the monasteries, you are first in line for the spoils. Your fortunes rise and fall through Henry’s reign. You come into your own in the autumn of 1536, when rebellion breaks out in the north; you suppress it with ferocity and relish. You are triumphant when you finally see off Cromwell, but that triumph doesn’t last; you are disgraced by the Katherine Howard affair, and later by the dynastic ambitions of your son, the Earl of Surrey. Though you are sentenced to death in 1546, you have a long wait in the Tower, and Henry dies the night before your scheduled execution. Unlike so many of your friends and enemies, you die in your bed in the reign of Queen Mary, in an England you don’t really recognise any more.

CHARLES BRANDON, DUKE OF SUFFOLK

A blundering hearty, a big man with a big beard. Six or seven years older than Henry, you are one of the tiltyard stars he looks up to when he is a young lad just taking up dangerous sports. Your relationship with him is warm and brotherly.

Your father, who was well-connected but ‘only’ a gentleman, died at Bosworth fighting for the Tudors, and you are brought to Court young, so grow up in an arena where you can shine. You fight with Henry in his small French war of 1531. You are considered the King’s principal favourite, are given offices and lands, and, five years into his reign, receive an enormous promotion to Duke of Suffolk. You are a good soldier, but considered over-promoted, a product of Henry’s enthusiasm, and more use in war than peace.

Then you mess everything up in the most spectacular way. You are sent to France for the marriage celebrations of Henry’s youngest sister, Mary, to the King of France. Louis XII is elderly and unattractive, Mary is a beauty of eighteen, and she has a crush on you; she marries under protest. Three months later, while you are still in France, Louis dies. Mary claims that Henry promised that if she would oblige him with the French alliance, she could choose her next husband herself. She chooses you. You think this is all a bit risky, but marry her because ‘I never saw woman weepe so.’ You then have to go back to England together and face Henry, who is so furious that there is a real possibility you will lose your head.

Wolsey intervenes and talks Henry around. An enormous fine is substituted for any other penalty. Most years Wolsey ‘forgets’ to collect it. You are wealthy because of the large pension Mary is given by the French, but the downside is that, for years, they treat you as their hired man at Henry’s Court.

You are an irrepressible man. You are soon back in Henry’s favour, though he sulks at you from time to time and falls out with you. As a politician, you are much less nimble than Norfolk, your East Anglian rival. Henry gives you nasty jobs, like trying to talk Katherine into compliance. You don’t get on with the Boleyns, and are offended by the family’s rise in the world. The rumour is that at some point before Henry’s marriage to Anne, you go to him and tell him that Anne has had an affair with Thomas Wyatt; you’re trying to save him from himself. At this point it’s the last thing Henry wishes to hear, and he kicks you out. You’re soon back at Court and happily blundering along. You love Henry, in spite of all.

You are baffled by Cromwell. But you find it best generally to do as he says.

After Mary Tudor’s death in 1533, you marry a fourteen-year-old heiress who was intended for your son. She grows up to be a witty and strong-willed religious reformer who keeps a small dog called Gardiner, which she shouts at in public: it’s the most successful joke of the English Reformation.

You remain rich. You remain honoured. You are a thread that connects Henry to his young self and to the England he inherited. You die in your bed, 1545. Henry pays for a magnificent funeral.

EUSTACHE CHAPUYS

You are born in Savoy, to a respectable but not wealthy family. You are a lawyer with university training, a meritocrat, able to make your way in the vast field of opportunity offered by service to the Holy Roman Emperor. You are in your late thirties (but, a fragile man, you seem older) when you come to London in 1529 to represent your master and to act as councillor and comforter to the embattled Queen Katherine. You will stay until 1545, with a brief intermission when diplomatic relations are broken off. That fact in itself is a testament to your endurance, and the faith placed in you by your distant boss.

You are a cultured man with a humorous turn of phrase. You are astute and subtle, but also passionately engaged in Katherine’s cause, and you give wholehearted commitment to her, and then to her daughter Mary. For you, this is not just a matter of duty, it’s personal. You labour under certain disadvantages; you don’t speak English. But who does, in the Europe of the 1530s? (How much English you understand is a matter of debate.) Visiting Henry’s Court, you never know what to expect. You have to swallow insults and threats, being snubbed and ignored. You are bobbing about in a sea of barbarians. Really, the only thing that makes life bearable is your regular suppers with Thomas Cromwell.

With Cromwell you can rattle along in colloquial French, your native tongue. You can pick up all the gossip. It may not be accurate, and you are aware that he may be teasing and misleading you, and yes, you know he’s the Antichrist. But you can’t help but like him, you tell the Emperor. He’s so generous and so entertaining and neighbourly. You do believe he’s on the Emperor’s side, if only he could be brought to say so.

It takes all your courage to face Henry. Luckily you have a lot. You will not only face him but needle him, probing the areas of vulnerability. Perhaps, you say, he will never have a son: God has his reasons. Henry bellows at you: ‘Am I not a man like other men? Am I not? Am I not?’

Your problem is this: your confidants are the old aristocratic families who support Katherine and Mary, and because you listen to them you misperceive the situation; you report to the Emperor several times that the English are ready to revolt and replace Henry, and you urge him to invade; in fact, the families you are involved with have little popular support. It is difficult for you to understand that the power structure is changing from below. There’s something you’re persistently not grasping. Perhaps it’s Cromwell. One day when you are deep in conversation, he starts to smile and can’t stop. You tell the Emperor that he has the grace to cover his mouth with his hand.

You are an arch-conspirator doomed to ineffectuality, a brave man on a failing mission. When the Emperor finally allows you to retire, on grounds of ill-health, you limp to the low countries and found a college for young men from your own country of Savoy. And you die peacefully, 1556: having made more of a mark on the history of England than you could ever have believed possible when you were sent among the savages.

SIR HENRY NORRIS

You are known as ‘gentle Norris’ the perfect courtier: emollient, but also, it seems, a man of genuine tact and kindness. You are chief of the King’s Privy Chamber, and Henry’s close friend; almost a brother: the man he wakes up to talk to, when he can’t sleep. Your closeness to him makes your friendship invaluable to other courtiers. You are at the centre of a network of patronage and favours. You are very powerful because you can control who is admitted to the King’s presence, and what he signs, and when. You grow discreetly rich. Like William Brereton, you are one of the ‘marcher lords’, with lands on the Welsh borders.

You are roughly Henry’s contemporary, and like him a star jouster, but you are also clever enough to take on a role in the management of his finances which is deliberately impenetrable: you are in charge of the ‘secret funds’.