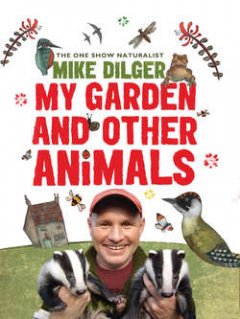

My Garden and Other Animals

Àâòîð:Mike Dilger

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Æàíð: ñàä è îãîðîä

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:344.57 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 417

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 344.57 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

My Garden and Other Animals

Mike Dilger

Christina Holvey

After the best part of forty years spent either living under his parents’ roof, in the tropical rainforests of three continents, a vast array of student digs or most recently a one-bedroom flat, The One Show’s Mike Dilger has at last bought a house – and with it, a (potentially) glorious garden…‘Potential’ was definitely the word that sprang to mind the very first time Mike and his partner Christina viewed their new ‘house-and-garden-to-be’ in a small rural village some eight miles south of Bristol.And so begins their year-long journey to create their very own wildlife sanctuary. From otters to badgers, chickens to hedgehogs, an orchard, a pond and compost bins, to the best birdlife imaginable, what began as a straightforward mission soon became the adventure of a lifetime.Illustrated throughout with beautiful black-and-white line drawings by Christina Holvey, Mike Dilger’s partner-in-crime, this light-hearted nature tale with a twist will appeal to wildlife enthusiasts and keen gardeners alike.

To the three women in my life:

Christina, Mum and Hilary

CONTENTS

Cover (#u8222cc87-6267-5506-bcd1-cc7dceaa970c)

Title Page (#u45d7cc9a-c8e3-594f-a4f6-597e3b596ac5)

Dedication (#u9602fb11-441c-581b-86dc-19b3f1321c58)

JANUARY – The Move (#u62c861ec-bc6b-5cb7-a99e-5fffab09c3fd)

FEBRUARY – Settling In and Knuckling Down (#u3fd4dfb1-2352-58a3-a217-26921157adcb)

MARCH – Springing into Action (#u28551c5d-45ee-5163-9cdd-2c6136e15f35)

APRIL – If You Dig It, They Will Come (#uf9fae14f-7cb7-57d1-bb55-33e348370f35)

MAY – More Wildlife than You Can Shake a Stick At (#litres_trial_promo)

JUNE – Who Says Moths Are Boring? (#litres_trial_promo)

JULY – Birds, Bats and Bugs by the Bucket-load (#litres_trial_promo)

AUGUST – The Sun-seekers Take Centre Stage (#litres_trial_promo)

SEPTEMBER – Harvesting the Fruits of our Labours (#litres_trial_promo)

OCTOBER – Departures, Arrivals and Residents (#litres_trial_promo)

NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER – The Temperature Drops but the Action Hots Up (#litres_trial_promo)

JANUARY – A Box, within a Box, within a Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

JANUARY (#ulink_5f8ecc92-22dc-59fc-a5d9-265c0e2d36d7)

THE MOVE (#ulink_5f8ecc92-22dc-59fc-a5d9-265c0e2d36d7)

‘Potential’ was definitely the word that sprang to mind the first time I clapped eyes on our new ‘house-and-garden-to-be’ in the small rural village of Chew Stoke, eight miles south of Bristol. On my partner Christina’s first viewing, the adjectives that sprung to her mind were ‘dilapidated’, ‘overpriced’ and ‘abandoned’. True, the unprepossessing semi we had just purchased was an ex-council property, hastily built in 1956 to house those displaced by the flooding of 1,200 acres of farmland that would ultimately form the Chew Valley Lake Reservoir. The house had also been sitting empty for the best part of a year, often not one of the best of signs. Don’t get me wrong, the property was more than habitable and according to our surveyor had been solidly built and was structurally sound, so at least it would be dry and warm. It was also a house perfectly designed with the phrase ‘bog-standard’ in mind, and certainly wouldn’t be the recipient of any architectural prizes.

From the outside the pebble-dashed facade smeared over concrete-block walls bore more than a passing resemblance to the colour of boiled shite; and with a combination of pine-panelling, hideously dated wallpaper and marigold-coloured walls, the interior offered little improvement. Even though the house was of cheap construction and stuck in a 1970s time warp, we had always declared this to be of little concern, as the real reason behind making the huge financial leap of faith had been the bell-bottom-jeans-shaped garden at the rear.

Surrounded on either side by mature gardens and playing fields, and book-ended with a small wooded bank leading to a stream that also represented the northern boundary of the property, the garden, whilst currently tired, unkempt and unloved, might just be in a position to offer huge promise under the right stewardship.

Along one of the boundaries – which divided the garden from an adjacent playing field – a small peeled-up section of fence and digging-marks in the lawn were a sign of the active presence of badgers. Surely, too, the stream might just play host to passing kingfishers, and the mini-woodland would certainly act as the perfect wildlife corridor for the comings and goings of everything from grey squirrels to great tits. Who wouldn’t bet on deer, foxes and woodpeckers making an appearance at some point too?

On our second viewing, endless possibilities as to how I could turn the garden into that mini nature reserve I yearned for began to run through my mind. My mouth followed suit, as I attempted to convince Christina of the simple, fun tasks we would be able to undertake to make the garden even more attractive to wildlife. ‘The bottom of the garden is where we should create the meadow, the pond would be next to the garage, we could then remove the alien species from the wooded bank and place the bug hotel in a quiet corner …’ I breathlessly declared in a soliloquy that would have left Hamlet short of a few words. Building up a head of steam, and getting even more carried away, I further stated that if we were successful in purchasing the property, I would personally take in hand the task of re-designing and re-wilding the garden, while maybe Christina could be persuaded to take on the slightly less glamorous task of redeveloping the house …

Now I hate to characterise our relationship as that of a ‘building-castles-in-the-sky’ type pitted against a cautious pragmatist, but broadly speaking it’s true. So I was in no position to argue when Christina put down a few conditions as to how the division of labour would work even IF we were to make an offer.

While on one hand she thought it churlish to ride roughshod over my naive optimism, she also felt compelled to point out the uncomfortable truth that I was not exactly the most practical of people, and so would have to give serious thought as to whether I would have the technical ‘know-how’ to carry out such ambitious plans. Not helping my argument was my track record; in my old communal garden in Bristol I had always tended to be a little work-shy when it came to any hard graft, and my ‘share’ of the gardening chores had usually consisted of little more than filling the bird-feeders. In response, I assured her in no uncertain terms that this time it would be different.

Feeling like I was winning the argument, I also offered an additional sweetener by suggesting that I would of course seek advice immediately if I felt out of my depth and promised I wouldn’t attempt anything foolhardy. Still unsure as to whom I was trying most to convince – her or myself – Christina suddenly and uncharacteristically threw caution to the wind, catching me totally off guard, by boldly stating that we should put in an offer without further ado! I could have kissed her … and in fact I did!

If anyone has ever tried to buy and sell property simultaneously they will understand why moving home is apparently right on the heels of death and divorce in that infamous list of ‘the most stressful things in life’. Once our offer was accepted the purchase moved through at double-quick time and moving day quickly followed.

It’s quite humbling seeing your worldly possessions – which have taken the best part of four decades to accumulate – reduced to a pile of cardboard boxes. This meant that Bill and his removal boys made short work of the flat’s contents, as I watched my dwelling of the last ten years reduced to an empty shell in just a couple of hours. Stopping only briefly to help themselves to more tea and the last of the biscuits, they hopped in the van and headed for our new home, leaving Christina and me behind to take the opportunity to say goodbye to a flat that had treated us to so many happy memories, but which we had now also undoubtedly outgrown. Without looking back, we closed the front door on our old lives and headed off to the vendors’ estate agents in Chew Stoke for our prize of two small keys, purchased for the mind-boggling sum of ?220,000.

We arrived at our new house just a couple of minutes after the removals lorry had pulled up on the drive – our drive. The ever-practical Christina proceeded to open up the house and take the lads on a guided tour, pointing out which boxes were to be deposited where, which gave me the chance to excuse myself from the hustle and bustle for just a moment so that I could take in the garden through an entirely new set of eyes. This time it was OUR garden!

Passing through the crude, asbestos-covered outhouse adjoining the kitchen at the back of the property and out of the back door, the functional concrete patio funnelled down to a nondescript path, bisecting a lawn which had definitely seen better days. Dotted randomly around the lawn were a couple of long-neglected rose-standards, a sickly collection of random shrubs which had been planted in all the wrong places (and in the wrong soil type), two different-sized birch trees, two rowan trees positioned far too close together for either to flourish, and a majestic if slightly lop-sided beech tree. The centre of the garden featured a huge and monumentally ugly wooden pergola that had been built in the form of an archway and which quite possibly could have been the only other man-made structure, apart from the Great Wall of China, viewable from outer space.

As I took in the view from the patio, our patio, the left-hand boundary was split between next door’s mature garden, with the further half running adjacent to a council playing field consisting of a goal post and a small playground for infants. Following down the right-hand side, the small creaky and rusting garden gate, which gave access to the drive at the side of the house, was attached to a short breeze-block wall, which in turn was adjoined to a great, hulking garage, shared with our neighbours. Finally, at the rear of the garage a panelled fence delineated the boundary between our property and that of next door’s, giving our garden privacy if nothing else.

Pacing down the garden, the lawn ran in a fairly regimented fashion for some 25 yards in a northwesterly direction, increasing in width from the patio (or hips) down to a tree-covered shady bank (or the ankles), revealing at its base the aforementioned water feature poking out of the bottom of the flares like a pair of grubby feet. From our very first visit, I had envisaged the water course, with the remarkably unprepossessing name of Strode Brook, as the ace in our deck of wildlife cards. Our section of the brook happened to join our property at the head of a large meander, meaning that the water met the garden at an angle before caressing the bank for a 10-yard stretch and retreating away again at a tangent. Inside the bend on the opposite bank was an area that looked like it was attached to a much larger and formal garden, but apart from a carefully mown strip that had been cut to allow access down to the brook, the rest of the land had obviously been left to glorious abandonment – making it great for nature.

In addition to the more formal part of the garden, the bank on our side was in desperate need of attention. Being on the outer bend of the meander, the constant water flow had acted like a huge corrosive brillo pad, and had seriously undercut the bank to such an extent that the small, steep section closest to the playing field looked decidedly unstable. Additionally, the adjacent and much shallower middle section had previously been used as a dumping ground for garden waste, giving the bank more the look of a rubbish dump than a wooded glade.

Dominating the air space above the bank were a sickly-looking and ivy-festooned oak, whose exposed roots crudely protruded out of the steep bank in the precipitous northwesterly corner, and a 60-foot-tall flagpole-straight ash in the centre. Both of these trees were surrounded by overgrown rank hazels and hawthorns, which hadn’t been touched for decades, and as a result had run amok in the understory, making an already dark north-facing slope look a Tolkienesque mini-Mirkwood. To put it bluntly, it was hard to see the wood for the trees!

The wooded bank and brook were partitioned off from the rest of the garden by a 3-foot-high wooden fence, covered in chicken wire, meaning any entry to the wood could only be achieved via a straddle at the height which tends to be awkward for males. Apparently the reason for this fence lay in the fact that the house had belonged to a very senior gentleman by the name of Mr Gregory, who had lived and raised a family here for the best part of 50 years until he was removed against his will, but for his own safety, into an old folks’ home nearby. Once an extremely keen gardener, in his latter years he suffered dementia but was still prone to impromptu walkabouts. During one of his mini-excursions down to the river, Mr Gregory had apparently accidentally uncovered a wasps’ nest, resulting in him being stung numerous times before tumbling down the bank and into the brook. Unable to haul himself out, apparently Mr Gregory had lain dazed and confused in the water for several hours until his faint cries for help were heard by neighbours.

As I wandered around the garden, with my chest puffed out and a heady mixture of excitement and trepidation welling up, little seemed to have changed since our last viewing, but in other ways everything had changed – the garden was now our responsibility! Contemplating the gravitas of what we had just taken on, my mood was instantly lightened as I spotted the first basal rosettes of primroses, pushing their way up exactly where I had planned the meadow to be! In little more than a month, their flowers would be providing the first boost of nectar for any emerging queen bumblebees that had successfully navigated the perils of hibernation.

As I got to my feet, one of those unforgettable red-letter moments suddenly occurred as a bird began to sing – my first thrush song in 2011. To make the moment even more special, it was not only being sung by my favourite songbird, but the individual in question had decided to belt out its mellifluous, strident and instantly recognisable song from the top of the oak tree, our oak tree, making it our song thrush!

When comparing birdsong, many say the nightingale is the finest songster in Britain, but I reckon in full swing the song thrush gives it a damn good run for its money. It’s difficult to explain with mere words the astonishing complexity, beauty and power of the song thrush’s song. Consisting of over a 100 exquisite, different musical phrases, each is repeated three or four times before the thrush draws breath in prelude to belting out another. It’s as though the gaps in between each phrase have evolved to give the song thrush a second to retrospectively admire his artistry. If so, he wasn’t the only one. As I stood there, listening to the virtuoso performance, it sounded like the bird was actually serenading me with a welcome song. The song thrush’s timing was impeccable, birdsong had never sounded sweeter and, more importantly, it made me feel that everything would be all right.

Landing back on Planet Earth with a bump and suddenly painfully aware as to how much had to be done, I wandered back in to find Bill, the Bristolian born and bred removals gaffer, espousing his philosophy to Christina on everything from Formula 1 to the finer points of interior decoration. Despite his West Country chatter constantly reverberating around the bare walls of the house, giving the impression that there was rather more tea drinking going on than what we were actually paying them to do, both Bill and his two henchmen, Derek and, yes, Derek, made light work of unloading the van. Having distributed all the boxes, they paused only briefly to have one more round of tea and biscuits and receive their all-important tip for a job well done before hands were shaken and they were off, leaving us and our boxes to a new life in the country.

The thing that instantly hit me, as I watched the removals van disappear from view, was the sound of silence – I could hear nothing. No trains or planes, no ambulances, no road-drills – nothing. It was a far cry from my old flat in central Bristol where the constant background hum of the city had been something I had taken for granted for far too long. Undoubtedly a townie born and bred, this would be my first attempt at living in the country. It would also be the first ever house I had lived in where I would be able to lie in bed and listen to the sounds of the dawn chorus. How exciting would that be?!

My hypnotic trance of imagining how wonderful it would be to listen to blackcaps before breakfast was suddenly broken by the sight and sound of another van outside trying its best to squeeze past my hurriedly parked car on the pavement. It was only then that I realised in our rush to open up for the removals guys that we had partially blocked the entrance to next door’s drive, and the owners of the other half of our semi. Not a good start. Dashing out to both apologise profusely and greet in one fell swoop, I offered the hand of friendship to my new neighbour, a wiry chap in his late forties called Andy, for whom an apology was deemed totally unnecessary and who seemed delighted that the other half of his property would finally be occupied. With big, bucket hands the texture of sandpaper, Andy was patently not someone who whiled away his professional life shuffling papers behind a desk; this was a man with a van, a man with technical ability and therefore someone worth cultivating a friendship with!

Despite being someone who crops up on telly on a regular basis to talk about everything from bumblebees to basking sharks, I’m often genuinely surprised when people recognise me. I suppose it’s because I forget that people will make the connection between the similarity of the chap appearing on the goggle-box and the person in the flesh. And while it’s very rarely an unpleasant experience when people want to meet you purely because you make regular appearances in the corner of their sitting rooms, it is a feeling, that unless you’re Paul McCartney or David Beckham, you never really get used to. So adopting my usual tactic of quickly changing the subject from his opening gambit of ‘I saw you on the telly last week’, I was quickly able to find out that not only was Andy a married man with three kids but also jointly ran a small plumbing business – handy indeed!

Apparently our arrival had been the talk of the street for the last couple of weeks, and whether this was down to my minor celebrity status or because anyone moving into a cul-de-sac in a small rural village would get the same level of scrutiny, I wasn’t sure. After pleasantries were exchanged, and as Andy patently seemed aware of my wildlife pedigree, he immediately implored me to come and see his garden, with which we shared a boundary for some 15 yards, so he could show me the array of feeders he had installed at various locations. Being a practical fellow, he had built a couple of lovely bespoke wooden feeding tables, rather than choosing the Dilger Way, which is usually to part with the cash at an inflated price instead.

It being a cold, wintery day, the local bird community was indeed piling in to his refuelling stations, and even without my trusty binoculars, in the matter of just a couple of minutes I was able to point out the usual cast of characters including great tit, blue tit, chaffinch, robin and dunnock. What I didn’t expect, though, was to see the tell-tale flashing white outer tail feathers of an altogether more unusual garden bird coming down to Andy’s offerings.

‘Reed bunting!’ I suddenly blurted out like a Tourette’s Syndrome sufferer, crudely cutting right across the middle of an entirely different discussion about the impressive amount of building work Andy had done to their house. To be fair, Andy also genuinely seemed thrilled by this find, declaring that he had never seen one before, and for me, back once again on the more comfortable subject of garden bird ecology rather than the intricacies of building regulations, I was able to give Andy a brief, impromptu lecture on the life history of the reed bunting.

Seemingly interested in my intricate knowledge of the bird’s ecology, and warming to the theme, Andy pointed out where they fed the local fox and then showed me another wildlife feature in their garden, which up until that point I hadn’t even noticed. Nestling behind an ugly leylandii and no more than two yards from our communal fence I was delighted to be shown a pond that Andy’s wife Lorraine, who apparently adores frogs, had cajoled her husband into digging back in 2007. Despite the feature looking like it needed a clear-out, as I could barely see any standing water for plants, Andy informed me, with immense pride, that both he and Lorraine regularly came down with a cuppa to watch both frogs and newts surfacing for a gulp of air before disappearing back down below to carry on with their aquatic shenanigans.

The reason for my delight at this news was twofold. Firstly it was wonderful that we had neighbours who were singing from the same song-sheet as us, in being keen to embrace the wildlife coming into their garden, rather than doing their level best to shut it out in favour of a sterile and – in my opinion – utterly soulless garden. Secondly, enticing frogs and newts into both our garden and the pond I would be creating later would surely be much easier if they only needed to travel a matter of a few yards across herbaceous border, rather than risk the perilous journey across acres of concrete and decking under the watchful eye of any number of predators.

Thanking Andy for the impromptu tour, and having had my offer of a glass of wine over the next couple of weeks accepted, I took my leave with the perfectly reasonable excuse that I had a house to unpack and shouldn’t be giving Christina the impression that I was purposefully shirking my box-emptying duties. I barely had one foot through the door when I heard a small voice behind me. Marjory, as her name turned out, was our neighbour on the other side, and the lady with whom we had joint custody over the drive, although we didn’t have a wall in common. Looking, to be honest, a touch unwell, Marjory must have been in her early fifties and was married to a chap called Dennis, who wouldn’t be popping out to say hello as he was unwell and vulnerable to the sharp winter chill. It turned out that Marjory was also fighting her own battles with illness and was not keen to linger too long on the doorstep either, so she offered a brief but warm welcome to the street.

I prepared to attack the boxes with gusto, but only after one vital task was carried out. I had to get my priorities right and so immediately put up a couple of my feeders from my old flat into our new garden – we wanted reed buntings too!

As the day-to-day living essentials slowly began to be unpacked we at last began to make some progress in turning the house from a warehouse into some kind of home. Concentrating on the kitchen, so that we would at least be able to eat, and the bedroom, so that we could at least sleep, pots were placed in bare cupboards, cutlery located in empty drawers and the bed reassembled before being made. Pausing only for a cup of tea, poured out of the newly located teapot, our conversation was cut short by a knock at the door.

Having arrived back from work, Andy’s wife Lorraine’s curiosity had obviously got the better of her as she decided that meeting her new neighbours was something that couldn’t wait until the following day. Talking in a thick Bristolian accent, which I have come to adore since moving to this part of the world, this blonde, super-slim mum of three was someone for whom talking was obviously a passion – what a chatterbox! In no time at all, we were all getting on like we had been friends for years, and very kindly she had no qualms in instantly offering her husband’s services on hearing our most pressing domestic concern as to why we had no water coming out of any of the hot taps.

With hungry adolescents to feed next door, Lorraine bid us goodnight, and barely had we closed the door when the third neighbour of the day came knocking, also keen to welcome us to the street. Pausing only briefly to contemplate the difference between our warm reception in Chew Stoke and the decidedly chillier welcome I had received on purchasing my previous flat in Bristol, when it had taken weeks for my neighbours just to acknowledge my existence, I invited Stuart in to find a seat amongst the boxes. Stuart, it has to be said, was someone I already knew well, as until recently he had been a TV editor. Hailing from the West Midlands town of Stafford, I had always felt a kindred spirit with Stuart’s Black Country roots and especially after we had discovered during one previous discourse on football that we must have coincidentally been at a number of the same Wolverhampton Wanderers matches as kids.

Whilst helping us drain the rest of a bottle of champagne we had brought with us to celebrate the move, Stu regaled us with all the gossip about those neighbours we hadn’t yet had the pleasure of meeting and declared how wonderful it was going to be to have a drinking partner on hand, who was, firstly, not a southerner, secondly, liked talking endlessly about football and, last but not least, was willing to neck a couple of pints every now and then.

Seeing we were visibly tiring from the physical and emotional exertions of the day – and perhaps more pertinently noting the last of the champagne had been drained and we couldn’t immediately locate any more alcohol without emptying 15 boxes, Stu left for a nightcap at his own home some 50 yards up the road, but not before giving both of us one more of his ‘welcome to the street’ hugs.

With a slightly bizarre and utterly forgettable first meal in our new house of grilled sausages and steamed vegetables, and unable to watch TV because it hadn’t yet been unpacked, we watched a DVD on my laptop, before going up to bed. Yes, we had finally moved out of a flat, and now, being in a proper grown-up house, we had stairs … and did I also mention we had a garden as well?!

FEBRUARY (#ulink_cc5aeafe-1e40-5110-b9c4-df7e3bdbd93c)

SETTLING IN AND KNUCKLING DOWN (#ulink_cc5aeafe-1e40-5110-b9c4-df7e3bdbd93c)

For the entire first week in our new house I’m not afraid to admit that the garden hardly got a look-in. Anyone who has ever moved house knows that the list of jobs needing to be done in order to get services up and running can seem endless. In fact, most of the week was spent waiting in various electronic queuing systems as I attempted to persuade everyone from internet providers to satellite installers to actually do what they were supposedly paid to do – help me out!

Having moved in on Monday 31 January, it was the following weekend before we were even able to surface for air and actually carve out some garden time. Finally, as our first Sunday in the house arrived, we hurriedly showered, dressed, excitedly gulped down our porridge and donned warm clothes. At last, a garden day!

Equipped with notebooks, we had decided that the wisest use of time would be to take both a full stock-take of what we actually had in the garden and, importantly, what state it was in, before brutal decisions were to be made as to what was for the chop. To say that in many ways we were starting with a blank slate would have been an understatement. From even the most cursory of glances around the garden it was obvious that many of the shrubs and trees had been neglected for so long they had become so malformed and twisted that to put them out of their misery might be the kindest course of action.

First to come under our scrutiny was a mature but hideously deformed wisteria, sprawled across the central half of the garage wall. The climber gave the impression more of a mangy dog tied to a rusty fence than the stately and regal vine we know it to be when given proper care and attention. Hanging by its own weight a couple of yards away from the wall in some places and virtually nailed to it elsewhere, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a plant more in need of a bit of TLC. After much debate we decided that it might not be a lost cause, but would need a ferocious short back-and-sides and total retraining to be given a fighting chance of making the grade.

The same, however, couldn’t be said for two small cherry trees behind the garage, which had been so brutally disfigured by the seemingly totally random action of lopping off of various limbs, and were in such poor condition that they looked half dead. After somewhat less of a debate we decided the best option here would be to remove them entirely and replace them with some healthy new fruit trees.

Another plant that we also had to give the Caligula-style thumbs down was the middle rowan tree, which, sandwiched between another similar-sized rowan and a big beech tree, had, in truth, never really been given enough room to flourish, making it look like the arboreal runt of the litter. Additionally, having been planted right in the middle of the bottom part of the lawn, its foliage would undoubtedly cast a huge shadow over the area I had set aside for the meadow, which as a habitat needed to be both light and airy for the flowers to flourish. Still, cutting down a mature tree is a decision that should never be taken lightly, as the nineteenth-century parson and gardener Canon Henry Ellacombe famously once said, ‘A garden without trees scarcely deserves to be called a garden.’

As we were keen to try and make our decisions based on what we thought would best suit the birds and the bees (amongst other groups), we were also mindful of the fact that surely the single most important way to make a garden more wildlife-friendly is to plant a tree. As stated by Ken Thompson in his wonderful wildlife gardening book, No Nettles Required, the more trees gardens have, the more beetles, bugs, snails, slugs, woodlice, social wasps, leaf-mining insects and moths will be attracted to use them for bed and breakfast, which in turn will prove a magnet for animals from higher up the food chain, such as birds and mammals. In addition, trees provide an extra dimension to gardens, enabling them to house more wildlife, just like we would now be in a position to fit more stuff into our new two-floored/three-bedroom house than in my previous single-bedroom flat.

However, taking everything into consideration, and with heavy hearts, we agreed that the garden would be better served in the long term if the rowan were removed. This same decision was also unfortunately extended to a small, sickly birch tree cowering in the shadow of a much larger and beautifully symmetrical birch adjacent to the playing field. A couple of small, nasty alien conifers on the wooded bank would also be for the chop, but these wouldn’t be missed for a second.

With other plants, though, our concord would be severely tested. Dotted along the border of the wood, for example, were three or four random shrubs, which in their winter plumage neither of us recognised. Early on in this process, Christina declared herself to be in the ‘if in doubt, chop it out’ camp, whilst I was a follower of the ‘cut in haste, repent at leisure’ school of thought, meaning I inevitably took on the roll of defence counsel, arguing that the shrubs should receive a stay of execution until we found out what they were. After much cross-examination, however, the prosecution (Christina) eventually relented and agreed to wait and see how they turned out before making any decisions about their future. I couldn’t help feeling, though, that this was just the first of many such battles of wills and that our strong-minded obstinacies would be tested on many more occasions over the next few months.

However, one job we were both keen to see achieved as soon as possible was the removal of Mr Gregory’s fence, which stood out as an ugly junction between garden and wooded bank, in contradiction to our preferred natural blending of all the habitats from back door to brook.

Another undertaking we instantly agreed upon would be to clear as much ivy as possible from the oak tree in the northwest corner. On the very first occasion I had viewed the property, I remember being utterly thrilled to find that a mature oak tree was part and parcel of the garden. However, with many of the tree’s roots exposed due to the undercutting nature of the brook, the fact that it was festooned from head to toe with ivy and the sheer amount of standing dead wood present, all seemed clearly to indicate that the tree had been struggling for some time.

In terms of an ability to attract wildlife to your garden, no one species can come even close to an English or pedunculate oak, with some naturalists having even likened an individual tree to the status of a nature reserve in its own right. With a staggering 284 different invertebrate species having been identified as living on oak trees, a diverse array of birds and mammals reliant on their acorns, a number of bat species roosting in the hollows and crevices, and great-spotted woodpeckers, nuthatches and treecreepers scouring the wood for food and nesting holes, it’s no surprise that even a struggling oak would be one of the garden’s real crown jewels.

The other side of the coin, of course, is that ivy has pretty good wildlife credentials too! Not only is ivy our only native, evergreen climber but it also provides the most wonderful late flourish of nectar in November and a ready supply of berries for our winter thrushes too. The latticework that forms as ivy crawls like a malevolent scaffold over other plants can also provide the perfect nooks and crannies for anything from hunting spiders to nesting spotted flycatchers. On this occasion, though, due to the abundance of ivy elsewhere on the bank, and particularly in amongst the hazels, it would have to give way to our not so mighty oak.

Feeling satisfied that we now had a healthy to-do list of hard and soft landscaping tasks, the only other pressing concern would be when to carry out the work. With spring only just around the corner, the time available to carry out tree surgery tasks, which should only really be done during the dormant winter period, was rapidly disappearing. On our walk round, we had already been delighted to spot the first snowdrop shoots emerging, and so the last thing we wanted would be for the sensitive woodland flora and meadow plants to be trampled underfoot at such a vulnerable time. In other words, I would need to find a tree surgeon on Monday morning!

Taking a break from arduous life and death decisions, we were delighted to invite our first non-familial visitors over in the afternoon. Nigel and his wife Cheryle are old friends I originally met through the annual birding fest that is the Rutland Birdfair. Nige, although he is far too modest to admit it, is one of Britain’s finest birders and has probably forgotten more about our feathered friends than I will ever know, whilst Cheryle, who claims to be a birding widow, also happens to be much more interested and knowledgeable than she lets on. Much more pertinent to this book, they are also the most wonderful gardeners and Christina and I were both keen to try and emulate elements of what they had managed to achieve in their own gorgeous Sussex garden over the last decade.

Arriving with a house-warming present in the form of a basket of native primroses, we were secretly hoping that rather than coming up with specific suggestions as to what we could put where, they would think it more useful to not allow us to become daunted by the enormous amount of work ahead of us but instead to be encouraging and supportive of our vision … and they didn’t disappoint.

The party of four almost instantly split, so while Cheryle and Christina wandered around the garden excitedly chattering away about building flower-rich herbaceous borders, Nigel and I scrambled around the wooded bank, indulging in one of every birder’s favourite games: guessing which birds we could expect to record in the garden over the next year. Kingfishers, grey wagtails and bullfinches were all excitedly discussed in turn as I proudly took Nigel on the first proper guided tour of our soon to be back-garden nature reserve. Our guests couldn’t have been better first visitors as they faithfully dished out encouraging words and inspiration in huge dollops.

Being a couple that have to work for a living, it would not be until the following weekend that we would have any opportunity to get stuck into our urgent ‘to-do’ list, as the evenings were still far too dark to carry out anything meaningful outside after work. However, during this downtime Christina was also able to put her artistic bent to good use by drawing a few basic sketches of the current layout of the garden in her notebook. Onto this plan we were then able to insert potential locations for the various wildlife-friendly features we planned to install later in the year. This enabled us, for example, to trial on paper the best places to dig the herbaceous borders and the pond – two essential components of any self-respecting wildlife garden, and features that would also be added to our garden, hopefully sooner rather than later!

The weekend duly arrived, with a promise of cold and clear weather, or, in other words, perfect conditions for our first practical day in the garden. Initially, prior to bowsaws and loppers being wielded, I wanted to ensure that sufficient numbers of ‘before’ photos were taken. These would then ensure that people visiting our beautiful swan of a garden would not only be able to marvel at the end product, but also be able to appreciate the full transformation from original ugly duckling too!

Keen to ensure her secateurs saw some action immediately, Christina decided to begin work on our postage-stamp-sized front garden. Having already agreed that tackling both gardens in the first year would have been a bridge too far, we had decided that the much bigger job of the back garden would take priority. There were, however, simple measures that could be carried out in the front to make it look more presentable. So while I snapped away, Christina set to heavily pruning a couple of long-neglected roses and re-training a tired-looking Japanese quince.

When I came round to the front I found Christina armed with secateurs and slowly disappearing behind a pile of severed branches. ‘It’s going to look a lot worse before it gets better’ was her pre-prepared answer to my tremulous question asking why she had really needed to remove so much. Pointing out that she had consulted none other than the mighty Bob Flowerdew, who had written a book on pruning which I had given to her for Christmas some six weeks earlier, I had to concede that on this occasion she knew better than me what she was doing.

Tidying up after Christina is a technique at which admittedly I have had much practice over the last six years, and so while she stood back to admire her handiwork it was left to me to ferry her brash through to the designated dumping zone – a dark corner of the garden behind the garage. This done, I was then keen to encourage her to put those massacring skills to good use in the back garden – we still had a ‘to-do’ list as long as my arm!

We had decided that, wherever possible, the wooded bank should mostly consist of native species, with the only exceptions being those ornamental aliens that had significant wildlife value. This meant that the two small confers, a leylandii cypress (my least favourite garden plant by some distance, for obvious reasons) and a stunted variegated male holly bush, were soon made short change of as I felled them with a bowsaw and Christina lopped the offending articles into more portable pieces. We then combined forces to drag the material over the fence and across to the dumping pile, which was now assuming ever-larger proportions. After all the talking and planning it felt great to at last get physical and stuck in, and the work was made even more enjoyable by the fact that the weather was so cold. As we grafted away whilst building up a sweat in the process we could see our own breath condensing in the cold air right in front of us.

Christina truly had the bit between her teeth, and, having seen off the aliens in a frenzy of lopping, wanted to turn her attentions to the ash tree in the centre of the bank, which she thought made the area look dark and dingy. Having already agreed that the rowan should be removed, to say I was incredibly reluctant to remove another mature native tree would have been an understatement. As the conversation tipped over from a robust difference of opinion into raised voices and then a full-blown argument, the crux became clear. Put simply, the subtext of the disagreement was about nothing less than the future direction of the garden; with Christina in one corner wanting primarily a garden while I wanted it to go down the Nature Reserve route.

The main battle line was going to be the wooded bank, with Christina maintaining it was too messy, and so by removing more vegetation and tidying it up, this would create more light in a dark corner of the garden. I countered that of course woodlands were often a bit dark and messy by their very nature, and therefore it would be better for the wildlife if the bank were to remain largely wild and woolly. I then hammered home my point by arguing that removing the ash tree would break a vital link in the chain, meaning that the continued canopy cover across the bottom of the garden would disappear. This would have the knock-on effect of denying lots of shy woodland birds and mammals the wildlife corridor they needed to move between the gardens. Building up another head of steam, I pointed out that in no way were we in any position to safely remove a mature tree with the tools and experience we had, so it would have to stay. But ever the conciliator, I offered as a compromise my promise that the more formal part of the garden, closer to the house, would be much more manicured and tidy.

While I would define my relationship with Christina as one consisting of reasonably regular arguments, we do make up soon after, and we were both in the act of apologising when interrupted by the sound of Lorraine’s voice next door, keen to hear how our first practical morning in the garden was going.

Pleased that our neighbours wanted to take such an interest in our plot, we filled them in on our rationale behind removing the aliens in order both to give more space to the (more cherished) native species and to attempt to open up the woodland a touch more to enable better views of the brook. On hearing the water mentioned, Lorraine’s eyes twinkled as she declared how her and Andy had always coveted our river frontage, and then surprised us by revealing that they had previously entertained the idea of trying to purchase the bottom of our garden after Mr Gregory had moved out. Privately of course both Christina and I had ‘too late now!’ thoughts; but ever the generous souls, I was quick to suggest that any time either needed a watery fix, they both had carte blanche to hop over the fence whenever they felt like it!

Lorraine also hilariously accused us of attempting to steal her garden birds with our now extensive offerings in the form of a stand-up bird table, a sunflower hearts feeder, a Niger feeder and a fat-ball dispenser. It was probably true that in the space of barely a week, and given the superior feed on offer in our garden, many of the birds had already swapped their notoriously fickle allegiances and were now choosing to spend most of their time emptying our feeders rather than theirs.

But joking aside, with our feeders in the centre, Andy and Lorraine’s to the left and a small feeding station in Dennis and Marjory’s garden immediately to our right, the local resident birds must surely have been some of the best fed in the southwest. Also, in the space of just a couple of weeks since we had moved in, it was not only astonishing how quickly the birds had found the food, but noticeable that we had already recorded a wider range of species at our feeders here than in the previous 10 years at our old garden flat in Bristol. Interestingly, the sheer quantity of birds was also much higher; it was not uncommon for us to peer out of the kitchen window to observe not only that every single perch was taken on all the feeders, but that queuing systems had often formed on the nearby bushes as well. The garden was quite literally alive with birds! This rich variety and abundance instantly brought two thoughts to my mind: firstly, what fun it would be compiling a garden bird list; and secondly, that it wouldn’t be too long before this huge concentration of small birds would register on a sparrowhawk’s radar!

With Christina away visiting friends overnight, I dragged myself out of bed the following morning for a spot of garden birdwatching, only momentarily undeterred by the miserable weather. One of the slight peculiarities, and immense irritations, of the house meant that there were comparatively few good vantage points from which to actually properly enjoy the garden, a fact we would rectify when we had sufficient cash to build the much-planned rear extension. In the meantime, the current best seat, or stand, in the house was from the landing window, halfway up the stairs.

Looking down, fully expecting a tit and finch-fest, I was aghast to see not a single bird on any of the feeders due to the dominating presence of a whole bunch of greedy grey squirrels. Four of these invaders could be counted, dotted across the garden and monopolising each feeder whilst the birds looked on helplessly from the nearby bushes, too intimidated to compete.

The grey squirrel is an animal that as a naturalist fills me with a whole range of mixed emotions. Brought over from the eastern side of North America and deliberately introduced on some twenty occasions between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, their rapid spread throughout England and Wales has proved the stuff of ecological nightmares. Now numbering as many as 2.5 million, this adaptable and hardy animal has become so widespread in our parks, gardens and woodlands that it is now quite probably the most commonly seen mammal in Britain, and as such is accepted by many as a wholly natural part of our wildlife.

To the neutral, the greys have obvious charm and appeal, and it has to be stated that they didn’t actually ask to be brought over to the UK and then become so vilified just for making an unqualified success of their new home. Unfortunately, the cold fact of the matter is that they have undoubtedly had a major impact on our native flora and fauna, which are poorly adapted to withstand their presence. Most well known is the contribution of the grey squirrel to the catastrophic decline of our native red squirrel, so much so that the red squirrel now only flourishes either in large parts of Scotland where the greys are still mostly absent, in a few grey-squirrel-free offshore islands or in large conifer belts ill-suited to the Yankee invader. Perhaps less understood by the public, though, are both the immense damage that grey squirrels cause to trees and the serious impact on many of our native, breeding woodland birds. Though many have called for their total extermination, this is totally impracticable, and, I’m afraid, irrespective of how we feel about the animal, they are definitely here to stay.

While a small part of me admired their brazen attitude as they reached across from the pergola, like supple athletes, to empty my feeders in double-quick time, the larger part of me was so indignant that I instinctively ran downstairs to shoo them out of the garden, momentarily forgetting I was in little more than my underpants. On seeing my naked flesh and hearing my accompanying ‘get out of it!’ they hurriedly spun round on their heels and triple-jumped their way back into the woodland at the bottom of the garden, disappearing in a matter of seconds.

I knew that with such a major food source on offer they would be back as soon as the coast was clear. So for the next hour I played a cat-and-mouse game with them, as I watched them quietly creep back into the garden and onto the feeders only for me to rush out and scare them off again (having got dressed in the meantime – of course!). After a while they either got the message that they were not welcome or had had their fill anyway, but no one was more aware than I was that this was little more than tokenism, and that I would ultimately have to adopt some serious anti-squirrel technologies if I didn’t want to spend the equivalent of the Greek national debt on bird food. So the ‘tree rats’ should enjoy the free handouts while they still could! With the squirrels at least temporarily pushed back, this at last gave me my first opportunity to watch the feeders being used by the animals they were designed for.

As the birds slowly returned, I delighted in the most wonderful hour watching blue tits, great tits, robins, chaffinches and greenfinches pile in despite the still awful weather. It’s been well known for at least a couple of decades that living with pets can lower blood pressure, lessen anxiety and boost our immunity, but because I can’t commit to owning a pet, due to the fact that I’m often away filming, I have to say that watching garden birds comes a very close second. It’s hard to explain the level of happiness I gain from watching the birds go about their daily business, but for someone who often spends his life dashing around at 70mph, it was important to take some time out on the hard shoulder every now and again.

I don’t claim to have been the only person to have uncovered this elixir of life, as the RSPB recently revealed the astonishing statistic that as many as 40 per cent of British households will feed their garden birds at some point during the year – more evidence of the power of wildlife as one of the best natural anti-depressants on the market.

The rain eventually receded and Christina returned, so we began to make preparations to launch ourselves into the garden for the afternoon’s activity: Operation Fence Dismantle. Earlier in the week I had sneakily taken a peek into next door’s garage, while they were putting out their recycling, and had noted a far more impressive collection of gardening tools and implements than we had yet been able to muster. Having made a mental note that some of these might come in handy at some point, barely a few days later I was now hoping they could be persuaded to lend us one of their crowbars. Knocking on the door, I fully expected it to be answered by Marjory and so was surprised to meet the tall, gaunt figure of Dennis, the Great Gatsby of our street, and the last of our immediate neighbours I had not yet met.

Though undeniably unwell, in addition to being both an ex-policeman and an utterly charming chap, Dennis also confirmed that he would be more than happy to lend us any of the tools we might need. Because his illness seriously affected his ability to undertake anything but the lightest of duties, he explained that he wasn’t in any position to wield tools, and so would be pleased to see them put to good use.

Since Dennis had lived in the house for the best part of 20 years, I was also to discover that he was the most enormous fountain of knowledge about both his and our garden and the adjacent brook. Both keen gardeners themselves, Dennis and Marjory regularly saw kingfishers whizzing up and down the brook, and in addition to seeing pheasants in the garden had even recorded roe deer on a couple of occasions too! He also tantalisingly revealed that whilst brown trout used to be commonplace in the brook, he hadn’t seen them for several years, possibly due to a combination of a couple of unfortunate pollution incidents upstream and a silting up of the stream bed. Trying, in part, to rectify the silt issue, he had even put a few heavy blocks in the water at the bottom of his garden to break up the water flow and perturb the bed, but this was in reality little more than piecemeal and had had little effect.

As the discussion turned to our garden, I excitedly gabbled about both the grand plans and the impressive list of birds we had already attracted to our feeders in the short time since moving in, before turning to the subject of how frustrated I was beginning to get with the bullying tactics of the squirrels. Dennis and Marjory had themselves encountered the same problems, until they had invested in special cage feeders designed to keep the squirrels at bay, and which had seemingly nipped the problem in the bud. Having not encountered anywhere near this level of mammalian feeder disturbance in Bristol, where the squirrels’ appearances were usually more novelty than irritation, it was obvious that my old feeders were now patently not up to the job and I would have to invest in some more!

Apparently I was not the first of Dennis’s next-door neighbours to have had this issue and he asked if I had heard about Mr Gregory’s battle with squirrels. Realising from my quizzical face that patently I hadn’t, he recounted how Mr Gregory had so detested their aggressive and domineering tactics that he had taken it upon himself to initiate a shooting and trapping campaign during his last few years in the house, claiming in the process a grand total of 212 squirrel scalps! What made the anecdote even more hilarious was that Lorraine (the neighbour to our other side) positively encouraged the squirrels into her garden and so was mortified to find her furry friends being so ruthlessly wiped out just over the garden fence. This meant that in order not to fall out with his neighbour, Mr Gregory had limited his operation to either night-time or when Lorraine was out at work – what a character!

Armed with all the correct tools, Christina and I quickly made short work of the fence line, as we firstly removed the wire rabbit-guard stapled to the front, then prised away the wooden rails with the borrowed crowbar and finally wiggled the posts free of their concrete footings. Standing back to admire our handiwork, the garden looked a touch strange without the one obstacle that had prevented the wildlife wandering freely between the wooded bank and the rest of the garden. Importantly, though, the garden and brook had now become one, and it was one more job off the list, too!

Stacking the wood behind the garage, we retreated to the kitchen for Christina to make a quick cuppa and for me to quickly catch up with how the English rugby team was doing against Italy. I had scarcely been given the chance to find out the score before hearing Christina’s urgent, shrill voice imploring me to come quickly to the kitchen. Seeing her nose pressed up against the window I followed suit, and was utterly astonished to see a male pheasant strutting around the garden as he cleared up the seed debris dropped by the tits and finches from the feeders, having obviously just strolled in via the new 15-yard wildlife entrance to the garden.

The pheasant is an introduced, and therefore in many purists’ eyes, a lesser species. Originally hailing from southeast Russia and Asia, it is thought to have been brought over to Britain by the Normans, and over time has become part and parcel of the British countryside and, in my considered opinion, a wonderful addition to our fauna too. The pheasant is also one of those species characterised by sexual dimorphism, which means that the sexes look completely different. The female pheasants often tend to be smaller, yellowy-brown and with marked flecking; colours and patterns which enable them to quickly melt into the background when incubating their clutch in spring; while the male, with his iridescent copper-coloured body, metallic green head, red facial wattles and ear tufts, could be described as a dandy with an attitude. Fatherhood is seemingly an alien concept for the male pheasant, as he plays little or no part in the rearing of his chicks. The males are more of the love ’em and leave ’em type, their sole aim being to assemble a harem of two or more females, which they will defend at all costs from other marauding males keen to chance their arm. Until they have been mated, that is, after which the males thoughtlessly abandon the females to their fate.

In our previous Bristol garden I would never have expected to see a pheasant, and even in our new garden I wouldn’t have shortened the odds that much at the chance of adding the species to my garden list. With a moment’s reflection, though, maybe its appearance shouldn’t have been that much of a surprise. For starters, Chew Stoke is a small, rural village set in the countryside, and due to our street being tucked away in the southeastern corner, as the pheasant walks our garden was probably no more than a couple of hundred yards from the nearest arable fields. Hadn’t Dennis also said only a couple of hours previously that they did occasionally turn up in his garden too?

I have watched pheasants in the British countryside on thousands of occasions, so what we were looking at, in isolation, wasn’t a particularly rare sighting. But watching one on our own lawn, I can officially confirm, was a hundred times better, because it was the most glorious vindication of our policy to break down one of the main barriers to our garden. By making our border porous, the effect had been the equivalent of laying down a green carpet of invitation – with the pheasant, hopefully, being the first of many more animals to accept!

True to my word that I would seek out help for those jobs technically out of my depth, and with time of the essence before spring would be upon us, I had arranged for a tree surgeon to come around and cost up some of the urgent work Christina and I had highlighted on our initial walk around. Rob was a tree surgeon of some repute in the southwest and was proud to report a wide and varied client list, which included our future monarch at his huge Tetbury estate in South Gloucestershire. If he was considered trustworthy enough for Prince Charles’s trees then he would certainly suffice for ours! What sold Rob’s services to me even more than his royal connections was the fact that Rob was not only born and bred in Chew Stoke, but by an amazing coincidence his parents still lived just around the corner. It was always good, wherever possible, to minimise the carbon footprint by keeping it local!

As his hulking old-school Land-Rover pulled on to the drive, (surely every tree surgeon’s chariot of choice), I was unsurprised to see a stocky chap emerging with legs only marginally slimmer than the sizes of mature tree trunks, who offered a handshake that was like having your hand placed in one of those bench-top vice-clamps – and then tightened to an uncomfortable level. While I waited for the blood to return to my hand, we moved straight into the garden, with Rob immediately proving charming and immensely knowledgeable in equal measure as he wandered around our mini-arboretum dispensing pearls of wisdom

Looking at the garden with fresh eyes, it was astonishing to see how in the space of just two short weeks, the garden had well and truly turned its head towards spring. While the male hazel catkins had been out for a while, it was only now that they had matured sufficiently to unleash their smoke-like sprinkles of pollen into the air at the slightest breeze. Some of these tiny packets of genetic material would then be ensured successful pollination by being intercepted in mid-drift by the bright-red erect styles of the tiny female flowers, arising like mini-phoenixes out of the otherwise naked hazel twigs. Daffodil leaves had also begun to emerge from a bewildering variety of locations around the garden, using the early spring rays to ensure sufficient food would be produced, via the miracle of photosynthesis, to produce a flower spike later that season. But botanical pride of place on the walk round easily went to the mini drifts of snowdrops which were scattered along the wooded bank in discrete pearly-white clusters.

The snowdrop curiously is also a plant with a whole host of synonyms, such as ‘February fairmaids’ or, according to the eighteenth-century poet Thomas Tickell, the wonderfully evocative name of ‘vegetable snow’. I personally think that the most intriguing name is ‘snow piercer’, so named because of the plant’s specially hardened leaf-tips, which have evolved to break through frozen ground. Despite some botanists harbouring doubts as to whether the snowdrop is indeed a native British flower, since many seemingly wild colonies may well have begun as garden escapes, what is without doubt is that as the austerity of winter comes to an end, the plant in full bloom is a welcome sign that many more floral delights are only just around the corner.

Looking up at the oak, and contrary to my thinking that the tree was on its last legs, Rob suggested that it would in all probability still outlive me! Having said that, he thought removing the ivy would certainly lighten the load and enable the tree to photosynthesise more easily, giving it a new lease of life. Whilst the beech tree would need no more than a few branches to be removed for safety and aesthetics, he also pointed out considerable damage to one of the main branches that I hadn’t previously spotted, which had been caused by those naughty grey squirrels’ unfortunate habit of bark-stripping.

Agreeing that the central rowan had always had insufficient space to flourish and did look in poor condition, Rob said that he would do his best to avoid too much damage to my newly demarked meadow whilst bringing it down. His chainsaw, we agreed, would also be taken to the huge rotten pergola in the centre of the lawn, which would have the dual benefit of both removing the garden’s biggest eyesore and opening up the meadow to a splash more of sunshine. I love it when a plan comes together!

As I was spending the following week away filming in Scotland, Christina had agreed to take a day’s holiday on the Friday to be both tea provider and photographer when Rob returned, this time with both chainsaw and colleagues to carry out the work. Catching the last flight back to Bristol, I arrived too late to see all the changes before nightfall and so had a frustrating wait until the following day before I was able to assess their handiwork.

Rushing out at first light with a coffee to inspect their efforts, I was flabbergasted at the difference. Just the removal of the rowan and the pergola alone had transformed the would-be meadow into one where light could penetrate. Apparently working from the top down to minimise damage to the ground flora, the rowan had been dismantled in less than an hour and had transmogrified into a neat pile of logs. Likewise the monstrous carbuncle that was the pergola had been turned into a neatly stacked pile of weathered timber – surely I would be able to find a multitude of uses for all that lovely wood? Other features permanently erased from the garden included the small birch tree cowering behind its bigger brother in the corner by the playing field and one of the two terribly disfigured cherry trees. Showing some artistic licence with the chainsaw, the other cherry tree had been thoughtfully converted to a bird table, with the table top having been fashioned out of a spliced section of the rowan’s trunk.

By systematically severing all the huge climbing stems and stripping the majority of the foliage out of the canopy, the oak was finally free of the ivy’s suffocating grip, and looked like it would now be able to breathe properly for the first time in a couple of decades. The beech had also been carefully pruned to both give it a good shape and to ensure not too many branches would fall into Marjory and Dennis’s garden. Finally, Rob had made sure that, wherever possible, trampling of all the lovely spring bulbs had been kept to a minimum – spring could now commence!

One of the little treats that we had long been planning, but until now had not found the time to carry out, was a mini-investigation of the surrounding land both upstream and downstream of our section of the brook. So, donning our wellingtons, Christina and I slithered down the bank and into the water for our very first exploratory paddle. As the water tinkled around our boots at a depth of no more than six inches, the first impression we were able to gain from this totally different perspective was how much lower the level of the water actually was below the bottom of the garden. Being a full three yards below the meadow meant that a storm of biblical proportions would have to occur before our property was in any danger of flooding. The downside of this disparity in height, however, also meant that, as the bank faced north, natural light would always be thin on the ground. It wasn’t until we were able to stand back and inspect the bank from this hitherto unseen angle that we realised how dark and dingy our little wood really was.

In fact, so dark was the steepest section of the bank below the oak tree that the only vibrant sign of life emanating from the gloom was provided by discrete clusters of the shade-loving hart’s-tongue fern, arising out of the bare earth like resplendent green shuttlecocks. With their strap-shaped leaves, which supposedly resemble a female deer’s tongue, this perennial evergreen is one of those plants that is always capable of brightening up the shadiest of woodland floors, so we were delighted it had chosen to take up residence on our bank too.

Being south-facing, the opposite bank, albeit distinctly shaded by the trees and shrubs from our bank, inevitably had more floral potential. In addition to the hart’s-tongue fern and the ubiquitous groundcover of ivy, I was a touch envious to encounter the first leaves of ramsons, or wild garlic, beginning to emerge above ground. Immediately recognisable in early spring by the sweet-and-sour cloying smell of its leaves and then later in the season by the drifts of white flowers as the plant monopolises huge areas, this was one woodland specialist I was hoping would also grace our side of the bank too.

Electing to explore downstream first, we had barely walked past the bottom of Marjory and Dennis’s garden before we heard a bird call we knew instantly. ‘Kingfisher!’ we both shouted in unison, as our ears caught its shrill characteristic whistle.

Aware of my interest in birds, I have lost track of the number of times that novice birdwatchers have asked me for any tips or advice as to how they might finally track down a sighting of a kingfisher. My response to this question is always the same; learning and recognising the call of this noisy and pugnacious little bird means it will often telegraph its arrival, giving you a moment’s preparation time to catch a glimpse as it whizzes past.

Sure enough, no more than a second after hearing the call, Christina spotted a blue bullet powering upstream towards us. Shocked at seeing our two huge looming presences standing in the middle of the brook, or its flight path, the bird veered away and took a short cut across the inner bend of the meander. Going at such speed, the kingfisher had to bank to make the turning, meaning we were treated to the most wonderful sighting of its orange underside before it righted itself and joined the brook again some 10 yards further upstream.

It was a thrilling encounter and an exciting moment as we realised that not only could we add kingfisher to our garden list, but having survived the harsh winter it might well be here all season. Breeding kingfishers at the bottom of our ex-council house garden – how good did that sound? I don’t mind telling you that at that moment I also performed a little spontaneous and aquatic jig of delight!

Buoyed by this wonderful find, we were soon brought back down to earth further downstream by the realisation that the brook, in addition to great wildlife, contained a disturbingly large amount of rubbish, both snagged in the water and littering the banks. Everything from plastic bottles to a fly-tipped pram and a bus-stop sign had somehow managed to find their way into the brook. Another job had just been added to our to-do list.

In some spots the brook was much more sluggish and deeper than at the bottom of our garden and so we had to either take a detour along the bank or move through the water very slowly to ensure it didn’t breach our wellington tops. Large sections of both banks seemed to be either attached to gardens or were just a tangled mess without an immediately identifiable owner. Scrambling up one area of bank, no more than a hundred yards from our garden, was a section dominated by alder trees at the water’s edge, where we were delighted to find a large and obviously very active badger sett. Occupying a little ridge which ran parallel with the stream, the sett consisted of at least half a dozen entrances, most of which were devoid of leaf litter, a sure-fire sign of recent use. Additionally, two of these entrances were so large that Christina could probably have joined the badgers down below, had she felt that way inclined, and there was evidence of fresh digging within the last 24 hours. Obviously the incumbents had just carried out their spring clean!

Retracing our steps back to the house and following the brook upstream, the bank on the south side soon flattened out to a small, wooded plateau littered with beer cans. Wondering how these had found their way here, it was not until a quick scout around that we realised that the playing field, which partly ran adjacent to our garden, also had a gate in the 6-foot-high fence, giving quick and easy access to the river bank – so this was where the local adolescents came for a clandestine lager or two! On the opposite side of the brook, the water had gouged out a steep sandy bank some 6 feet high, which seemed perfect for a nesting kingfisher. On closer inspection, my instinct had patently been right as we soon uncovered a couple of long-discarded and now partially collapsed holes that were probably indicative of breeding attempts from previous seasons. I made a mental note that I simply had to bring a four-pack back down here later in the year to spend an evening watching the kingfishers – if we were lucky enough to have them breed in the same bank again.

With many other gardens backing onto the brook, it also gave us the perfect opportunity for a nose around, or a kingfisher’s-eye view, of all of our waterside neighbours. As you would expect, the gardens were a mixed bunch, with some beautifully laid-out, whilst others were in a ramshackle state and obviously hadn’t been touched for years. Peering over the bank, we were amazed to see one large garden with a model railway running the whole way around its perimeter – how utterly bizarre!

With March rapidly approaching, the next urgent job on the ever-growing to-do list was to get some nest boxes in the garden, as the resident blue tits, great tits and robins would probably already have begun prospecting potential nest sites for the oncoming breeding season. If I were to collect house points for effort in attracting birds to our garden, then I would be awarded one point for every different species spotted actually feeding in the garden, but would be granted an immediate 10 house points for every pair which successfully raises a brood. For any self-respecting garden naturalist, playing host to nesting birds in your garden should really be the greatest accolade, as it says that you are getting much more right than wrong in your attempt to make your garden the ultimate wildlife-friendly destination.

In an ideal world, I would love to have handmade all my own nest boxes, as it is incredibly easy and instructions can be found on the internet. However, as time was of the essence, we decided that we would have to splash the cash. Anyone who has ever purchased a nest box knows that they come in innumerable shapes and sizes, so after much debate down at our local garden centre about the merits of each design, we went for four of the classic boxes as favoured by blue and great tits, three open nest boxes as preferred by robins and spotted flycatchers, and a large box fraternised by jackdaws or tawny owls. On reaching the tills with our trolley full to the brim, I was left with the distinct feeling that creating this haven of wildlife – if done properly – would not only need time and effort but possibly a large proportion of our expendable income too!

With the sun streaming through our bedroom window, it was obvious that the morning after our mercy dash to the garden centre would be beautifully cold and crisp – in fact the perfect day for putting up nest boxes. Having run out of milk for our ‘pre-erecting nest boxes coffee’, I offered to walk round to the local store to grab a couple of pints whilst Christina sorted out breakfast. Enjoying the warming effect of the low winter sun on my face, I must have gone no more than 50 yards from the house when I heard the unmistakable sound of a male chaffinch belting out his mating song – which in an instant signalled the immediate cessation of winter and beginning of spring.

My RSPB Handbook of British Birds describes the chaffinch’s song as ‘a short, fast and rather dry descending series of trills that accelerates and ends with a flourish’, which I suppose is a reasonable interpretation of an unremarkable song. But the description does nothing to explain the huge symbolism of what the song represents, as I always look upon it as signifying the gateway to my favourite season. The song operates like a drum-roll for spring to let us know that the bumblebees and butterflies are about to emerge, bud burst will begin and the breeding season can swing into action.

We had decided that the first place to erect one of the boxes would be on the oak trunk, which had just been liberated from its ivy stranglehold. Marking the northwest boundary of our property, the previous owners had erected a steel fence which butted up to the tree and then topped it off with a barbed-wire strand which had been crudely nailed straight into the oak’s trunk.

Keen to remove this impediment to the tree’s health before we put up the nest box, I attacked the fencing staples with my pliers, momentarily forgetting that I was right on the edge of the precipice created by the brook. As I reached round to remove the last staple, my foot slipped on the mud, causing me to lose my balance, and a split-second later I was careering off the edge bound for the water below – and to think, I’m ashamed to admit, that I had stifled a laugh when I heard about Mr Gregory’s unscheduled visit to the same brook a few years earlier! Also aware of the fact that my ridiculously expensive camera was still around my shoulder, I closed my eyes and prepared for a big splash, no small amount of pain on hitting the water and the instigation of a large insurance claim to replace my soon-to-be-ruined camera. Thump! I opened my eyes to find that I hadn’t hit the water at all, as I had straddled one of the huge oak roots protruding from the bank. Despite the fact that the tree had saved both me and my photography kit, I didn’t get away scot-free, as I had pulled a groin muscle, slightly bruised my err … undercarriage and cut a couple of fingers. Nevertheless, it was a lucky escape.

Elsewhere in the garden, Christina hadn’t been aware of my fall until she turned round on hearing my pathetic cries for help as I came out of my momentary daze and realised I was struggling to get either up or down. On peering over the edge of the bank Christina wasn’t sure whether to be worried for me or laugh her socks off at my ridiculous predicament. After passing the camera to her, which had fortunately not been damaged by my tumble, I was eventually able to scramble back up the bank, and recount what had happened, feeling somewhat embarrassed and chastened by the whole experience.

Deciding that because of my sore groin it would probably be easier if Christina put up the tree nest boxes, leaving her klutz of a boyfriend to hold the ladder and pass up the tools, we set about finishing the job. Starting with the tit boxes first, we elected to attach one each to the trunks of the oak and the birch whilst embedding the other two in the centre of the hazel stands. Two of the open nest boxes were nailed at differing heights to the playing field fence line whilst the other was placed on the dividing fence between our garden and Marjory and Dennis’s.

The only problem we encountered for the rest of the morning was in our attempt to put up the large nest box. We were struggling to find a place to put it where it would have a chance of being used, without endangering our lives in the process. After a half-hearted attempt to put the box some 15 feet up in the beech tree, using a combination of our ladder and then a bit of tree-climbing, we decided, after my experience a few hours earlier, that it was probably a touch too ambitious and dangerous, and so left the nest box in the garage for another breeding season. Because the nest box was of the open-fronted variety, I was also fearful that if anything did try to nest in there, the chicks would have been an easy target for those opportunistic squirrels.

We planned to spend some time in our postage-stamp-sized front garden in the afternoon, so I went in to prepare lunch, only for Christina to dash in minutes later urging me back out into the garden. As I looked down the garden you could have blown me over with a feather as we watched a prospecting blue tit stick its head back out of the nest box on the birch tree, scarcely more than an hour after we had put it up. Talk about an instant response!

MARCH (#ulink_88d2b0e4-c64c-5a81-a1b3-9ecd0b664100)

SPRINGING INTO ACTION (#ulink_88d2b0e4-c64c-5a81-a1b3-9ecd0b664100)