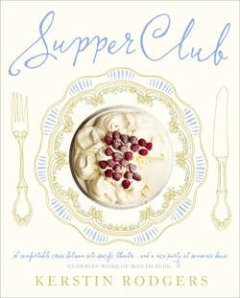

Supper Club: Recipes and notes from the underground restaurant

Àâòîð:Kerstin Rodgers

Æàíð: êóëèíàðèÿ

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:344.57 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 110

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 344.57 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Supper Club: Recipes and notes from the underground restaurant

Kerstin Rodgers

‘Outrageously Good’ – Kate NashThis is the innovative, fun and utterly delicious cookbook from London’s premier supperclub.For a fixed price and a bottle of wine, people all over the world are sitting down in the homes of strangers to enjoy a lovingly prepared, restaurant-quality dinner. From New York to London to Cuba, these supper clubs and pop-up restaurants offer an alternative experience for those looking for a new, fun and exciting dining experience. You won’t find these restaurants in any city guide – they are strictly for those in-the-know, if you’re lucky enough to get a much coveted reservation.Supper Club is homage to the secret restaurant phenomenon. In this wildly creative and wonderfully eccentric cookbook by Kerstin Rodgers, owner of London’s famous Underground Restaurant, you’ll find Kerstin’s inventive and delicious recipes and themed menus, peppered with her helpful hints, tips and wild experiences. You’ll also be treated to Kerstin’s down-to-earth advice on how to run your own home restaurant, and a directory of other supper clubs of note around the world (just don’t tell anyone). In few other cookbooks will you find recipes such as elderflower fritters alongside home favourites such as Macaroni and cheese.Supper Club will appeal to home chefs and budding underground restaurateurs alike, and is a must-have for anyone who wants to experience the cutting edge of eating in.Recipes Include:Yuzu cevicheTinda MasalaThai corn fritters with dipping sauceChav’s White chocolate trifle with MalibuSavoury yoghurt granita with caramelised pine nuts, preserved lemons and torn basilPork Belly with sage and fennel stuffingBabaganoushKissing ChutneyThai Green Spinach soupEggplant parmesan or melanzana alla parmigianaSalt Baked fishEdanamePear, walnut and gorgonzola saladBloody MarmiteyTomatillo salsa with chilli en adobeDuck breast with rhubarb compoteCrack Cocaine Padron PeppersButterbeerFocaccia bread ‘shots’Bergamot posset with crystallised thyme with lavender shortbread

To all the single parents,

you are superheroes!

Contents

Cover (#u61270c08-c929-526a-aa87-0d360da0fa57)

Title Page (#uce7e8e84-b9a0-57fa-ad6f-3933ffadcda6)

Part One – The Notes (#u720055db-dd44-59d4-a628-a23c7f876816)

Introduction (#u107286e1-d52c-5020-bafa-3f70720b84ee)

My Food (#u3e483fb9-1582-5b2b-af7e-79d98758eaa4)

The Home Restaurant (#ufa5b5b71-5b3e-570b-9993-24a180d38d81)

The ‘Pop-Up’ Restaurant (#ua08cf06e-d1b5-589f-990e-ea6441696601)

Variety (#u43ada050-0ba5-5cd0-bda9-4e614e1191ff)

Why Start a Supper Club? (#ud3f2a008-c7a9-5bcb-ac81-d447c070a19c)

The Story of MsMarmiteLover (#ue5d6140f-f772-5737-b8c6-a934f11c5f8f)

How to Start Your Own Underground Restaurant (#uff87ffcd-5032-5c9c-bf78-8af10c42e51d)

Cooking Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two – The Recipes (#litres_trial_promo)

Cocktails and Nibbles (#litres_trial_promo)

Daiquiri (#litres_trial_promo)

Kir Royale (#litres_trial_promo)

Butterbeer (#litres_trial_promo)

Butterscotch Schnapps (#litres_trial_promo)

Popcorn with Lime & Chipotle Sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Crack-Cocaine Padr?n Peppers (#litres_trial_promo)

Chipotle Sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Bombay Mix (#litres_trial_promo)

Five-Seed Roast (#litres_trial_promo)

Marinated Olives (#litres_trial_promo)

Dukkah (#litres_trial_promo)

Baba Ganoush (#litres_trial_promo)

Pitta Bread (#litres_trial_promo)

Focaccia Bread Shots (#litres_trial_promo)

A Word About Flour: (#litres_trial_promo)

Marmite on Toast with Crispy Seaweed (#litres_trial_promo)

Bloody Marmitey (#litres_trial_promo)

Edamame (#litres_trial_promo)

Nice Touches (#litres_trial_promo)

Starters and Sides (#litres_trial_promo)

Baked Jalape?o Poppers (#litres_trial_promo)

Thai Corn Fritters with Sweet and Sour Cucumber Dipping Sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Vadai with Yoghurt and Flaked Jaggery (#litres_trial_promo)

Butternut Squash & Feta Filo Triangles Edged with Poppy Seeds (#litres_trial_promo)

Gratin of Salsify (#litres_trial_promo)

Dolmas (#litres_trial_promo)

Tempura (#litres_trial_promo)

Kushi Katsu: Japanese Motorway Caf? Sarnie (#litres_trial_promo)

Steamed Artichokes with Dijon Mustard Dressing (#litres_trial_promo)

Chillies en Nogada (#litres_trial_promo)

Beef and Spring Onion Chinese Dumplings (From Mama Lan’s Supper Club) (#litres_trial_promo)

Savoury Yoghurt Granita with Caramelised Pine Nuts, Preserved Lemons and Torn Basil (#litres_trial_promo)

Gammodoki (From Horton Jupiter) (#litres_trial_promo)

Yuzu Ceviche (#litres_trial_promo)

Soups (#litres_trial_promo)

Marmite French Onion Soup (#litres_trial_promo)

Vegetable Stock (#litres_trial_promo)

Roasted Cherry Tomato and Garlic Soup (#litres_trial_promo)

Sorrel Soup (#litres_trial_promo)

Thai Green Spinach Soup (#litres_trial_promo)

Cockaleekie without the Cock! (#litres_trial_promo)

Magic Wizard Pumpkin Soup (#litres_trial_promo)

Salads (#litres_trial_promo)

French Beans with Tofu &Walnut sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Palm Heart Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Mint, Coriander, Onion &Pomegranate Cachumber (#litres_trial_promo)

Really Great Caesar Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Broad Bean, Feta & Mint salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Pear, Walnut & Gorgonzola Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

M?che with Egg & Dijon Mustard Dressing (#litres_trial_promo)

Grilled Halloumi & Roasted Pepper Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Vegetarian Main Courses (#litres_trial_promo)

Baked Vacherin (Fondue for Cheats) (#litres_trial_promo)

Eggplant Parmesan (Melanzane Alla Parmigiana) (#litres_trial_promo)

Quenelles (#litres_trial_promo)

Basic Curry Spice Mix (#litres_trial_promo)

Chilli Sin Carne with all the Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Salsa Asado (#litres_trial_promo)

Tomatillo Salsa with Chilli En Adobe (#litres_trial_promo)

Guacamole (#litres_trial_promo)

Corn Tortillas (#litres_trial_promo)

Twitter Curry (From Spicy Hardeep Singh Kholi) (#litres_trial_promo)

Kissing Chutney (#litres_trial_promo)

Sikh Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Coconut Dahl (#litres_trial_promo)

Tinda Masala (#litres_trial_promo)

Jewelled Basmati (#litres_trial_promo)

Butternut Squash & Blue Cheese Risotto (#litres_trial_promo)

Fresh Pasta Home-Made (#litres_trial_promo)

Spinach & Ricotta Cannelloni (#litres_trial_promo)

Il Timpano (#litres_trial_promo)

Really Good Mac & Cheese (#litres_trial_promo)

Cr?pes ‘You Creep in, Get a Cr?pe and Creep Out ’ Victoria Wood on a Date in a Cr?perie. (#litres_trial_promo)

Fish Main Courses (#litres_trial_promo)

Gratin Dauphinoise with Smoked Salmon (#litres_trial_promo)

Curing your Own Salmon (#litres_trial_promo)

Grilled Sardines with Mint (#litres_trial_promo)

Salt-Baked Fish (#litres_trial_promo)

Marmite Cheese on Smoked Haddock (#litres_trial_promo)

Spaghetti Al Cartoccio (#litres_trial_promo)

Thai-Style Fish in Banana Leaves with Coconut Rice (#litres_trial_promo)

Stargazy Pie (#litres_trial_promo)

Meat Main Courses (#litres_trial_promo)

Spiced Slow-roasted Leg of Lamb with Mujadara (From The Shed) (#litres_trial_promo)

Mujadara (#litres_trial_promo)

Casa Saltshaker Locro (From Casa Saltshaker, Buenos Aires) (#litres_trial_promo)

Quintessential Chicken (From Ben Greeno) (#litres_trial_promo)

Shin of Beef Rag? (From Sheen Suppers) (#litres_trial_promo)

Pork Belly with Sage and Fennel Stuffing (From Plum Kitchen, New Zealand) (#litres_trial_promo)

Rambling Sunday Roast of Pork Belly with Black Pudding, Thyme and Honey Parsnips and Cider Gravy (From the Rambling Restaurant) (#litres_trial_promo)

Duck Breast with Rhubarb Compote (From Lex Eats) (#litres_trial_promo)

Slow-cooked Sirloin Steak with Wholegrain Nut Crust, Roasted Baby Beets and Baby Spinach Catalan, Served with Truffle Potato Pur?e (From The Loft) (#litres_trial_promo)

Desserts (#litres_trial_promo)

Mousse au Chocolat Orange with Cointreau and Choc-dipped Physalis (#litres_trial_promo)

Tarte Tatin with Cr?me Fra?che Ice Cream (#litres_trial_promo)

Cr?me Fra?che Ice Cream (#litres_trial_promo)

Bergamot Posset with Crystallised Thyme & Lavender Shortbread (#litres_trial_promo)

Saffron Kulfi with Almond & Cardamom Tuile Biscuits (#litres_trial_promo)

Giant Pavlova (#litres_trial_promo)

Salted Caramel (#litres_trial_promo)

Clafoutis (#litres_trial_promo)

Easy Apple Strudel (#litres_trial_promo)

Chav’s White Chocolate Trifle with Malibu (#litres_trial_promo)

Candied Oranges, Lemons & Limes (#litres_trial_promo)

Cheese Course (#litres_trial_promo)

Rye Crispbread (#litres_trial_promo)

Fig Compote (#litres_trial_promo)

Themed Menus (#litres_trial_promo)

Elvis Night (#litres_trial_promo)

Deep-fried Peanut Butter Sandwiches (#litres_trial_promo)

Deep-fried Dill Pickles (#litres_trial_promo)

Shuna’s Cornbread (#litres_trial_promo)

Candied Yams (#litres_trial_promo)

Corn-on-the-Cob (#litres_trial_promo)

Cheese ‘n‘ Grits (#litres_trial_promo)

Collard Greens (#litres_trial_promo)

Blackened Catfish (#litres_trial_promo)

Two Types of Fries (#litres_trial_promo)

Brokeback Baked Beans (#litres_trial_promo)

7UP Salad (#litres_trial_promo)

Pecan Pie (#litres_trial_promo)

Midnight Feast: The Black Album (#litres_trial_promo)

Black Russian Cocktail (#litres_trial_promo)

Black Olive Tapenade (#litres_trial_promo)

Black Cod’s Roe on Black Bread (#litres_trial_promo)

Black Sesame Salmon Balls with an Avocado Oil and Black Vinegar Dipping Sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Nori Handrolls Stuffed with Black Rice, Black Kale, Black Carrot and Aubergine (#litres_trial_promo)

Beluga Lentils with Goat’s Cheese (#litres_trial_promo)

Squid-ink Tortelloni Stuffed with Goat’s Cheese & Lemon Zest with a Death Trumpet Mushroom Cream Sauce (#litres_trial_promo)

Marmite Chocolate Cupcakes (#litres_trial_promo)

Flower Menu (#litres_trial_promo)

Cava with Sweet Yellow Rocket Flowers or Hibiscus Flowers (#litres_trial_promo)

Courgette Flowers Stuffed with Goat’s Cheese (#litres_trial_promo)

Elderflower Champagne (#litres_trial_promo)

Ginger Beer (#litres_trial_promo)

Elderflower Fritters (#litres_trial_promo)

Marigold Bread (#litres_trial_promo)

Nasturtium Leaf Salad with Marigold petals & plum tomatoes (#litres_trial_promo)

Asparagus Mimosa (#litres_trial_promo)

Mint & White Chocolate Ice Cream (#litres_trial_promo)

Flower Ice Bowl (#litres_trial_promo)

How to Crystallise Herbs & Flowers (#litres_trial_promo)

Mint Tea with Pine Nuts (#litres_trial_promo)

Supper Club Directory

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One – The Notes

Introduction

We think of the restaurant as an ancient institution but in fact it dates back only a couple of hundred years to the French Revolution. Chefs emerging from the households of a destroyed aristocratic class no longer had jobs. The very idea of a restaurant at this time was revolutionary: a place where anybody who had the money could pay to eat. Suddenly, traders were sitting cheek by jowl with aristos; housewives next to duchesses. They were being waited on, not by their own private staff but by serveurs, people who would serve anyone with the financial means.

That was the first revolution in eating out. 2009 was the year of the supper club. A new revolution.

London is a newcomer to the supper-club scene, although in the 1930s an experimental dining club ‘The Half Hundred’, held in the modernist Isokon building in Hampstead, was attended by the artists and intellectuals of the day, such as Agatha Christie and Henry Moore.

In fact, the very idea of food being important to British culture is quite a recent phenomenon. Britain leads the world in protesting against GM foods and declining fish stocks, while also promoting vegetarianism, animal rights and the growing of your own vegetables. At the same time, Britain, especially London, is a powerhouse of youth and alternative culture. Underground restaurants were just waiting to happen…

Home restaurants have been popular in Latin America since the Cuban revolution, where paladares (Spanish for ‘roof of the mouth’ or ‘palate’) were set up in response to government restrictions and the American embargo.

The pioneers of this phenomenon in London were Horton Jupiter, musician and host of supper club The Secret Ingredient, and me, under my blogging pseudonym of MsMarmiteLover. We both sprang from an alternative sub-culture in London where people lived cheaply, ate at donation-only squat caf?s and ‘skipped’ food from supermarket bins (‘dumpster diving’), partly in response to sheer poverty, but also as a protest against consumer waste.

In January 2009, Horton opened his living room to strangers. Two weeks later I did the same thing. Now a new home restaurant or pop-up is starting every week in London, and is gradually rippling out to the rest of Britain. I get daily e-mails from all over the country, asking me advice on how to set up a home restaurant. In this book I set out a ‘how to’, a manual.

When I started The Underground Restaurant in January 2009, I announced it on my blog and was shocked when a hidden readership emerged out of the digital woodwork and left comments, asking if they could attend the first dinner. Things continued from there. It was difficult to handle the onslaught of interest from the world’s media at the same time as working out how to run a restaurant in my living room.

I called my living-room diner ‘The Underground Restaurant’, which has become a generic name for this type of restaurant. It’s not really a restaurant, more a table d’h?te with a fixed menu. It’s not literally ‘underground’ either (I have been asked this!), but conceptually, in the 60s counter-culture sense. The legality of supper clubs is not yet clear and the risks will be explored later in this book (#ulink_8c6112dc-f64e-55cb-88e9-420cdc495a2a).

My Food

I try to avoid classic restaurant dishes. I’ll make things that restaurants don’t have the time or business model to make, like Stargazy Pie (#litres_trial_promo) or a Croquembouche. Another difference from the average restaurant: I don’t cook or eat meat, I’m a pescatarian. Things like pat?, liver, kidneys, faggots and gristle in my favourite spaghetti sauce always revolted me. I feel uncomfortable with eating animals. I have to suspend my imagination even to eat fish, but I do like the taste. I’m not a proselytising vegetarian, I’ve had relationships with meat-eaters, snogged them and everything. But you won’t find any meat recipes from me in this book. Fear not, there are guest meat recipes from other supper clubs.

As the chef/patronne of my supper club, I don’t feel obliged to serve meat. I can cook whatever I feel like. I often make themed meals based on the season, the date (eg Feast of the Assumption), popular culture (film night, Elvis, Patrick O’Brian) a type of food, (umami night) or a nationality (Arabian night).

At first, I charged very little and made a loss; I could not continue like that. I now charge a price comparable with a restaurant, but at least you know you are getting everything, the whole experience – from aperitif to coffee – included. It’s not cheaper, but why should it be? To dine at The Underground Restaurant is a unique experience. I don’t ‘turn tables’: you have a table for the night. It’s economic because you can bring your own wine, and you come secure in the knowledge that you have paid for every aspect of the meal. In restaurants people often share a dessert or decide to save money by having coffee at home.

At a home restaurant, people have to come with realistic expectations; it’s not a normal restaurant. For instance, I had an Italian family come for a brunch: one asked for a latte, the other an espresso. I laughed. I don’t have a big expensive coffee machine. You eat what I give you. It’s more like going to your mum’s house (if your mum was stylish and an original cook).

If going to a supper club was initially a novelty, people are getting used to the fact that home restaurants now form part of the eating-out landscape. Culturally, home restaurants are a boon for tourists: you can eat in English homes and learn about the British in this way.

The Home Restaurant

There are different types of underground restaurant. The ‘home restaurant’ is, for me, the most interesting, intimate and authentic of the supper-club genre.

The notion of the home as a private space is quite recent, only since Victorian times. The home restaurant is blurring the lines between public, work and family space. You are welcoming complete strangers into your home. Your taste in d?cor, your books, your music taste, your crockery, your bathroom toiletries, even your underwear (if, like me, you sometimes forget to tidy it from the drying line) is open to inspection.

The home restaurant appeals to the foodie and the voyeur. It is as if the TV programme Come Dine With Me (in which strangers eat at someone’s house and award them points) has mated with Masterchef (the TV cookery competition for amateur chefs hoping to become professional) and Through the Keyhole (in which the camera films inside a private home and a panel has to guess the celebrity to whom it belongs).

At a home restaurant, the food is usually cooked by a talented amateur or a wannabe professional. It can be a rehearsal for opening a commercial restaurant. In the case of Nuno Mendez, chef of former restaurant Bacchus, his home restaurant (supper club The Loft) was a way of testing out menus in preparation for opening his subsequent restaurant Viajante. His restaurant now open, Nuno retained The Loft as a showcase for talented young chefs.

For David Clasen, who has been running the supper club First Weekend since 2003, his home restaurant is ‘a slow burn. I’m building up skills, menus and a clientele for the part-time restaurant I hope to open in a few years’.

Even pop stars’ wives are getting in on the act: Ronnie Wood’s ex-wife Jo Wood has opened up her mansion and gardens to the public for ‘Mrs Paisley’s Lashings’. Does Jo, who has cooked nutritional food for The Rolling Stones on tour, stand sweating behind the stove? No, she has hired in a pro, Arthur Potts Dawson, from Kings Cross restaurant Acorn House. The price is equally starry…?160 per person. Doubtless, guests are hoping to be sat next to diners like Mick Jagger, who happens to be Arthur Potts Dawson’s uncle.

The ‘Pop-Up’ Restaurant

Occurring in unusual places – an abandoned shop, a boathouse, a garden or a hired location – it’s ‘pop-up’ because it is temporary, either in terms of the space or the amount of time it will remain open. Frequently the chefs are professionals and the waiting staff experienced. Prices tend to be higher. But it is a great opportunity for young chefs without their own restaurants to showcase their food.

Another type of ‘pop-up’ is Latitudinal Cuisine (#litres_trial_promo), organised by architect Alex Haw. Nobody pays; it’s based on participation. Every week a supper is held at a different house and the guests bring a dish based on the latitude or longitude announced in a lengthy e-mail essay by Alex. The week I went, this included an eclectic menu based on places ranging from Graz in Austria, the Congo and Svalbard, to Bari in Italy, Sweden and Libya.

For Sam Bompas, of food event artists Bompas & Carr, a pop-up restaurant is an installation, a mix of art and food. He’s held events experimenting with glow-in-the-dark jelly, the history of food, a breathable cocktail and a ‘parliamentary’ pop-up that served cocktails and food and held debates around the time of the election. Each event is innovative and researched. Sam obviously has his ear to the ground in the food world, as he attended my very first dinner, bringing along jellies for the guests.

Pop-up restaurants also include legitimate outdoor pop-ups in marquees, such as The Griffin, which opens to the public for six weeks every summer round the back of Grays Inn, London. This pop-up is more legal than most; its clients are usually barristers and judges.

Variety

There is a huge variety of styles of underground restaurant. Some operate weekly, some monthly, some just when they feel like it. The locations can vary from a council flat, a suburban semi, a bedsit, a ch?teau, a shed, a boat, a warehouse. Some underground restaurants can feed 50 people at a time; others are more intimate affairs of 6–10 people. I’ve even held private dinners for two in my garden shed!

The phenomenon is very site specific. Each underground restaurant is as individual as its host…and you have the freedom to fit it around your lifestyle. The style will depend on your space, even the amount of knives and forks you own…

David Clasen serves only 12 people because he happens to own just 12 place settings, three tables and a tiny kitchen. I have a large Victorian garden flat, so can fit up to 30 people at a time in my living room. When the weather is good, we can spill out into my garden and balcony. I host my evenings on a Saturday because my daughter is at school during the week and I felt it might be a little distracting for her to arrive home from school on a weekday faced with a horde of strangers in the living room.

Horton Jupiter can fit 10 people comfortably in his council-flat living room. Horton is in a band, ‘They came from the stars, I saw them…’ and therefore needs weekends off for gigs.

Artist Tony Hornecker’s extraordinary studio space, a little crooked house in the back streets of the East End (soon host to the 2012 Olympics, let’s really show the world how we entertain, eh?), displays his talents as a set designer. The food, although good, is almost secondary to the setting. He sits diners all over his house; couples can even book his bedroom!

Why Start a Supper Club?

Do you make money from a home restaurant? Not much. The home chef hasn’t got access to trade discounts and suppliers because they order in only small amounts. Even so, as the banking system collapsed and parliamentary democracy trembled in the wake of financial scandal, were supper clubs a response to the recession?

Many of the home-restaurant chefs certainly started up because of financial necessity. I’m a single mother, raising a child on a low income. This is a way of starting my own business from my home. Working away from home is always an issue for parents, particularly mothers, so a home restaurant is a perfect entrepreneurial match.

But it has its problems too: the rest of your family must become accustomed to sharing their private space with strangers. There are sacrifices. These I will elaborate on later in the book.

Tony Hornecker, on why he started his home restaurant, The Pale Blue Door, in his studio, says that ‘because of the recession, I wasn’t getting any work. I was literally living on onions. Now at least I can pay my rent.’

While it is probably no coincidence that the ubiquity of supper clubs in Buenos Aires increased in the wake of their financial crisis in 2003, more important, I believe, than the ‘recession story’ is the opportunity to socialise. Most home restaurants are based in big cities, where, despite the crowds, it’s hard to get to know other people. One of the things that surprised me at first was the social-networking aspect of my underground restaurant. As the weeks went on, I realised that larger mixed tables worked better than many small tables. Part of the attraction was meeting other people face to face, people that you may so far have ‘met’ only on the Internet. Even though you are with people you don’t know, there is an instant connection, you are all strangers in a strange land, and there are common subjects – the food, the house, and the cook – to talk about.

It’s also great for lone diners. Women in particular may feel uncomfortable going alone to a restaurant on a Saturday night. Large mixed tables remove the stigma, the embarrassment of dining alone publicly. You won’t feel like a saddo!

The first home-restaurant marriage surely is not far away. (Although once, a couple who had got together six weeks previously at Horton Jupiter’s restaurant split up while at my restaurant. As the hostess, I was left with the responsibility of making sure the abandoned, drunk and scantily dressed ex-girlfriend got home safely.)

I must admit, in the back of my mind, I thought I could meet someone through my supper club. The reality is that I’m too busy in the kitchen, perspiring the welcome cocktail, staggering around in heels and a smeared apron, and shouting at people, for this to have been a successful romantic venture.

In a sense, a home restaurant, which celebrates the oldest communal activity in the world – eating dinner together – has been made possible by the Internet, by new media. It’s turning the virtual into the real.

I had been blogging about food for a couple of years before starting The Underground Restaurant. I mentioned in a post that it was about to open and was delighted that some readers immediately requested an invitation.

From the beginning, The Underground Restaurant has been open to complete strangers, people I have never met. Other supper clubs trod more warily, with a long period entertaining friends and acquaintances before opening up to the public. I remember Horton announcing, slightly nervously, on Facebook, two months after opening, ‘This is the first evening that nobody I know will be coming!’

Some supper-club hosts vet their guests carefully. I had problems getting a reservation at one when I booked in my real name, sending at least ten e-mails without reply. When I booked under MsMarmiteLover, I immediately got a reply: ‘You should have said who you were,’ he announced, ‘You would have got in straight away!’ This supper-club host doesn’t want lone diners who ‘make everybody feel uncomfortable sitting there on their own,’ or anybody that he considers would not ‘fit in’. This host is as exclusive as I am inclusive. As I said, everybody has their own style.

Is all this a rejection of overpriced formal restaurants? I liken the home restaurant phenomenon to the punk revolution of 1976. At that time, young people had become frustrated with mega-rich pop stars escaping to America to become tax exiles, hanging out with Princess Margaret on the island of Mustique, and creating concept albums filled with meandering songs. (Pop is, after all, a grassroots movement in which talented people from humble beginnings can ascend the social ladder.) Young people wanted three-minute pop tunes and bands playing local venues for which they could afford tickets. Punk was born.

Most celebrated chefs today are media creatures, for the most part male, and rarely behind the stove of the restaurant that bears their name. Cooking professionally is hard work and long hours, for little pay. Bullying is rife in the industry, both physical and psychological. Even the names, the rankings – chef de rang, chef de partie – have their roots in the army. The glory of cooking in a professional restaurant lies only in repeat bookings and murmurs of ‘My compliments to the chef.’

Like dinosaur prog rockers from the 70s, ‘sleb’ chefs have sometimes turned their backs on the audience. Chefs can make more money from TV shows, cookbooks and endorsed cookware than from their restaurants. Like haute-couture fashion houses, the money is not in the clothes but in the merchandising, the perfume. Like women’s magazines, the gloss and the perfect lifestyle of today’s cookbooks can both inspire aspiration and depression.

For me, my Underground Restaurant is a chance to put into practice some of my political ideals: do-it-yourself culture, making good food available to everyone at a reasonable price, improving the image of vegetarian food. I am probably the only restaurant in the world that reserves cheaper seats for the unemployed, people on benefits, those who may not be able to afford to eat out.

Unlike France, Italy and Spain, there exists a culinary apartheid in Britain. Poorer people are confined to ethnic restaurants, fast food and chains when eating out. London is one of the most expensive cities in the world in which to eat out and most people simply can’t afford to eat at good restaurants. Our food markets, while improving, do not offer the freshness, affordability and diversity of European street markets. A home restaurant in every neighbourhood could be a route to change, raising the status of home-cooked food.

Trust is also important. Many commercial restaurants simply cannot be trusted to provide cooked-from-scratch fresh food or meals for special diets. I cheffed in a ‘vegetarian’ caf? at festivals that served bacon sandwiches in the morning because they were such a money spinner. The bacon and the vegetarian food were regularly cut up on the same chopping boards, prepared with the same knife. But the fashion for food intolerances can drive the home chef up the wall, too.

Some customers like the idea of exclusivity. Food blogger Krista of Londonelicious describes the appeal for her:

‘I went to Bacchus, but chef Nuno Mendez did not come to the table to personally describe each dish as he did at The Loft. This is way more special.’ This exclusivity comes at a price, though… ?120 per head.

Other guests love the idea of illegality, the notion that they could get busted. It’s not so much extreme sport, but the thrill of extreme dining. I have to admit, I do play up this aspect. Guests are asked to memorise a password before they can enter. I tell them that if we get raided by the police, start singing Happy Birthday! (In reality I’ve had policemen come as guests and they don’t have a problem with it!) It evokes memories of the 1920s prohibition era, as does the Argentinean term for underground restaurants, puertas cerradas – ‘closed door restaurants’.

A SUPPER CLUB IS A CHANCE TO CATAPULT YOURSELF INSTANTLY TO THE POSITION OF CHEF/PATRON:

…if you are too old or have too many family commitments to work your way through the ranks.

…if it is too late to go to catering college, to train via the accepted route.

…if you just want to cook part time, want a practice run before you open a mainstream restaurant.

…if you lack the finances to rent a premises, hire staff, enter into contracts with suppliers.

…if you have discovered, like me, rather late in the day, that this is where your heart lies.

Open an underground restaurant. I double-dare you…

The Story of MsMarmiteLover

I’ve always cooked. I remember the first dish: I was at nursery school and we baked chocolate butterfly cakes. Even all these years later, I remember how incredibly pleased I was with myself. It seemed a magical process. The trick of removing the top of the cake and cutting it in half to make wings was unbelievably cool. I became obsessed with cakes for a while after that. I’d get up early before my parents awoke and get busy cake-mixing. One day I decided to go a step further and turn the oven on. At 6 a.m. my parents awoke to the smell of burning plastic – I’d decided to bake my cake in a red plastic bowl. My mum came downstairs and opened her brand new oven; the red plastic was dripping through the bars of the rack. ‘You can’t heat up plastic!’ she cried. And for a while, that was the end of my baking career.

At the age of eight I was given a copy of Good Housekeeping’s Children’s Cookbook, which gave step-by-step instructions in black-and-white photographs of how to make a cup of tea or toast a slice of bread. Many of the instructions started with ‘First comb your hair…’ From this I learnt how to make macaroni cheese, fudge, peppermint creams and coconut ice.

When I was 15, I got a Saturday job at WHSmith. A new series of magazines had come out: Supercook. As staff, I got a ten per cent discount. Every week, a copy of Supercook was set aside for me, illustrated with typically 70s food photography showing wood-varnished chickens and earthenware pots. The colour brown was big in the 70s. Three months into the subscription, I made a Sunday lunch for the family, from Supercook recipes. As the series was in alphabetic order – a letter a month – I’d only got up to ‘C’, which limited the menu to…Cabbage, Chestnut stuffing, Chicken, Chocolate mousse.

Eventually I got the sack from WHSmith. Not for my punky spiked green and blue hair (to match the uniform, I was pushing the brand!) but for lateness. This meant that my Supercook issues stopped at ‘R’. I could not cook dishes starting with the letter ‘S’.

This didn’t deter me. I hosted a dinner party for a guy I thought fancied me. My menu was sophisticated: grilled grapefruit halves with glac? cherries, spaghetti bolognese (the only thing beginning with ‘S’ that I knew how to cook) and baked apples with custard. I had 12 guests, a ridiculously large amount for a 15-year-old. Grilling the grapefruits took forever and the main course didn’t get served until 11 p.m., by which time I was exhausted and drunk. Then my friend Clare kissed the object of my affection, a cocky guy with a mullet, whose millionaire father owned a plastic-bag factory. Story of my life: I’m sweating in the kitchen, imagining that my beautiful food would attract soul mates, while my friends are outside, wearing platforms, face glitter and flicked-up fringes, getting some action. What idiot came up with that phrase, ‘The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach’? It’s so not true.

When I left school, however, I decided to become a photographer, not a cook. Becoming a chef didn’t seem within the realm of possibilities. TV schedules were not full of cookery game shows as they are now. I loved the Galloping Gourmet and Fanny Cradock, but that was about it. My mum had a boxed set of Elizabeth David books, but there were no photos and I wouldn’t cook something unless it had a photo with it. She also had Robert Carrier cooking cards. These were in a cardboard box, like a file, and each one had a photograph of the dish.

My parents had sophisticated tastes in food. They had a house in France, a wrecked stone cottage with twelfth-century walls that were three-feet thick and a fireplace you could sit in. It was outside a small town named Condom, 100km south of Bordeaux in the Aquitaine region. Every school holiday it took us two days to drive there from London. The route to Condom was devised around recommendations in a red, plastic-bound volume, Le Guide des Relais Routiers de France. It was our job as kids in the back seat to spot the Routier logo. Usually they were proper restaurants, cheap, with a set menu and a parking lot full of lorries. Sometimes, however, you would go into a private house listed in the guide and eat in a woman’s kitchen, just one table covered with a chequered oilcloth. The woman would be wearing her flowery apron and cooking in front of you, turning around from her gas stove to plonk platters down on the table. Once for hors d’oeuvres we were given a dish of long red radishes with their green tops still on, a basket of fresh baguette with a sourdough tang, a small hunk of unsalted butter and a pile of salt. We all looked at it, including my parents, not quite knowing what we were supposed to do with this array of ingredients. The son of the woman, noticing our hesitation, laughed and showed us what to do: he cut a little cross in the end of the radish, smeared on a scrape of butter, then dipped it in salt, crunching the radish with torn-off chunks of bread. So simple, just fresh produce, but so delicious.

Wine was always included and everybody, even children, had a little carafe of rough red table wine. This impressed us kids enormously, we felt so grown-up.

In those days I ate meat. My favourite meal, when we were allowed to order ? la carte, was steak and chips. One night near Rouen, we stopped at a hotel-restaurant. We kids, as usual, ordered steak frites. There were strange mutterings from the proprietor; there seemed to be a problem. But then no, it was fine, steak frites it was.

When the steak arrived, I bit into it.

‘What do you think?’ asked my dad.

‘It’s yummy. Sort of sweet.’

‘But you like it?’ he asked, in a rare display of interest in my opinion.

‘Yeah, it’s great,’ I enthused.

At the end of the meal my dad told us that it was horse meat.

So I’ve been brought up to eat well, to eat adventurously. My parents loved to travel even before they had kids; my dad, in an attempt to woo my mum, suggested that they go on a cheap tour of Europe. They hitched everywhere. Their budget was the equivalent of 50p a day. When they arrived in Cologne, my mum perused the menu at a restaurant and chose the cheapest thing. The menu being in German, she had no idea what she would be getting.

The waiter, with a silver-domed platter held high, weaved his way through the crowded restaurant. He placed the heavy silver dish on their table and, with a dramatic flourish, lifted off the lid. There, squatting angrily on the platter, an apple between its teeth, was an entire pig’s head. That was what my mother had ordered.

She gasped.

‘I’m not eating that!’ she exclaimed.

The whole restaurant, having followed the progress of the waiter, burst into laughter.

When things had calmed down, my dad whispered:

‘Don’t worry. I’ll eat it.’

As he commenced tucking in, a smile playing around his lips, my mother breathed out heavily:

‘I think you should know that I’m pregnant.’

It turns out that I was conceived in Minori, Italy, earlier in the trip. My dad, unperturbed, gestured with his fork towards the pig’s head and said:

‘I suppose we are going to have to marry you, then.’

So, as I was growing up, my family travelled through France, Italy and Spain every summer, stopping at Relais Routiers and family-run restaurants en route. Every winter we went skiing, eating fondue, raclette and drinking gl?hwein in Austria and Switzerland.

Once, my father insisted on taking us to a very expensive and reputable restaurant in Spain, near Malaga. We drove through winding mountain roads for hours to get there. My father ordered the best Rioja wine and taught us to savour its aroma from specially designed glasses. The speciality of the house was the seafood platter, which the waiter displayed in its raw state: it was dominated by a two-foot long sprawling langoustine, its eyes waggling around on stalks. My mum and we kids recoiled. Moments later, the whole platter returned: everything was split in half like a Damien Hirst sculpture and steaming! We refused to eat anything at all. It didn’t help that we were all sunburnt and tired. My dad was very angry.

My father will eat anything. It’s probably a reaction to war-time rationing. He’ll suck the bone marrow out of bones…not just from his plate, from yours too. He was intolerant of any fussiness at the table; we were pushed to eat frog’s legs and snails.

The snail incident was traumatic; we stayed in a farmhouse in France that belonged to family friends. The back room was dedicated to keeping snails, mostly kept in buckets; their digestive systems were ‘cleaned’ by being fed on bread for three days. Some of the snails escaped, they were everywhere, shiny trails on the chalky walls and stone floor. We went to a nearby restaurant that served snails stuffed with garlic, butter and parsley. My dad exhorted us to try.

‘Go on, just one.’

We three kids spent the next couple of days in bed with terrible diarrhoea. Our bedroom was upstairs in this farmhouse, thankfully far from the snail room, but there was no inside toilet. We spent two days shitting in a communal bucket as we were too ill to make it to the outside toilet. I never tried snails again.

On this same trip, same farmhouse, my dad woke us early.

‘We are going mushroom hunting,’ he whispered.

Sleepy-eyed, we stepped out into the dark and walked what seemed like forever, down the poplar-lined French country roads to the forest. On this holiday, my dad read us a chapter every night, with all the voices, from The Lord of the Rings, by the huge fireplace. The forest, when we arrived, seemed to me to be populated by elves, trolls and hobbits. After hours of searching, dawn came, and all we had found were three orange chanterelle mushrooms and a few ceps. We carried them back to the farmhouse, where they were fried in butter and garlic. Nothing has tasted better since, although we found the texture of the ceps a little slimy. I still love to forage for mushrooms in the autumn.

In London, special occasions were marked with dinner at Robert Carrier’s restaurant in Islington. I remember my first meal there: every course was tiny and perfectly arranged on the plate. Sights that are now common in haute cuisine, like French beans all lined up in a neat pile, exactly the same size, were objects of wonder back then. You felt you wouldn’t get enough to eat, but of course you did.

One night my dad brought home an entire octopus. He laid out this huge tentacled creature, with its large body full of ink, on the kitchen table. We kids came down to stare at this monster. My dad was excited; my mum left the room, muttering, ‘I’ll leave you to it.’

In those days Google didn’t exist. My mother’s cookbooks didn’t explain how to deal with octopus either. So my dad, a journalist, dealt with this crisis just as he would a story: call an expert, a good ‘source’, and ask them. He phoned Robert Carrier, whom he didn’t know and who was at that time probably the most famous chef in Britain, at his restaurant. In the middle of service. Robert Carrier, a very helpful gentleman, came to the phone and patiently explained to my father how to remove the ink sac, prepare and cook this octopus. He followed the instructions, amazed, despite his habitual cheek (something I seem to have inherited) at getting this help.

Of course, none of us would touch it.

My background is part Italian, part Irish and entrepreneurial to the core. My great-grandmother Nanny Savino had a shop in her Holloway council flat. I loved visiting her; the hallways were lined with bottles of Tizer and R. White’s lemonade, the bathtub with pickled pig’s trotters, the kitchen provided toffee apples and apple fritters and, most excitingly, under her enormous cast-iron bed were rustling brown boxes with the illicit earthy smell of tobacco – Woodbines, Player’s Weights cigarettes and matches. People would come to the door and ask to buy cheap fags from ‘Mary’. Her real name was Assunta but no-one could pronounce it. She came to Britain at the age of 16, before the First World War, from the small town of Minori, south of Naples. During the Second World War, the Italians were our enemies and her radio was confiscated. She wasn’t put in a camp, as several of her sons were in the British army. I never met my great-grandad, but from family stories he seems to have been a skinny man, under the iron fist of my enormous, rectangular, black-clad Nan. They started small businesses: a cart selling home-made ice-cream in the streets of Islington, then an Italian caf?. Even at the age of 80, infirm with arthritis, Nan was doing business from her house. It’s the Neapolitan way; even today there are independent street-sellers in Naples.

One of my most memorable meals was when I was eight years old, and we drove to Minori to see the Italian side of the family, many of whom lived in caves (the front looked like an apartment but the back was a rocky cave). My father’s godfather turned out to be the mayor of the village. He took us to a darkened restaurant, the best in the locality. The godfather wore a crisp white shirt, a tailored dark suit and gold glinted about his cuffs. The small finger on his right hand had a long, curly, yellowing nail. This was an Italian peasant’s way of saying ‘I don’t have to work the land.’ The waiters lined up as if it were a royal visit. Nobody kissed the godfather’s ring, but that wouldn’t have been out of place.

As we left, my brother piped up:

‘Dad, I like this restaurant, we don’t even have to pay!’

My parents hushed him. A few days later, we were invited to the godfather’s house. We had to climb a small mountain of lemon groves; the lemons were half a foot long, with thick knobbly skins, so sweet you could eat them straight off the plant. I remember being so thirsty as we made our way up the dusty lemon grove. The crickets were deafening and the sun beat down. At the top we were welcomed by the widowed godfather’s two 16-year-old daughters – twins I think – who had made us dinner. This time the godfather was wearing a white vest and blue work trousers. This dinner lasted for hours; they had pulled out all the stops: antipasti, pasta, a seafood course, a fish course, a red-meat course, a white-meat course, salads, vegetables, cheeses, puddings. It was the first time I had cannelloni, large stuffed rolls home-made by the young girls. It was a tremendous feat, this banquet, especially for such young cooks. We didn’t speak Italian (they spoke in dialect) and they didn’t speak English. After a few courses, we were struggling; my brother saved the day by groaning and clutching his stomach. At first the girls found this funny and offered him camomile tea but eventually his cries grew so loud and insistent that we had an excuse to leave.

Looking back, meals like this were the inspiration behind The Underground Restaurant, an attempt to recreate the languorous feasts of the continent. You see, the buzz for me, the shiver up my spine, the ‘Oh wow, this is all worth it’ moment, lies in these words: ‘community’, ‘sharing’, ‘experimentation’, ‘dismantling boundaries’. My instrument is food, that which binds us all (sounds a bit Lord of the Rings, doesn’t it?). We all need to eat. Many of us love to cook.

Feeding is how mothers show their love for their families. It’s how countries and communities and religions and families can identify with each other. Meals are memories, milestones in our lives; the first date, the lover that proposed, the husband that did not return for dinner (in retrospect, the first signs of divorce), the tentative feeding of your baby, the family discussions and rows around the table as the children grow up. Sunday lunch, one of the few remaining meals requiring mandatory attendance for family members, is where you might bring a prospective mate to meet the relatives. When I travel, new tastes and smells are intrinsic in recalling that country. Food divides us too: religions are distinguished via what they will not eat or drink.

My philosophy stems from a punk, do-it-yourself ethic. You don’t need a degree in music to start a band, you don’t need permission from the authorities or a catering-college diploma to start a restaurant. Some of the best chefs are self-taught: Raymond Blanc and Heston Blumenthal are two well-known examples. Sometimes, not having a formal education can help you think differently, laterally.

I had an unusual route into food. I did not go to catering college, I did not do a ‘stage’ at a top restaurant, I have not worked in ‘normal’ restaurants at all. Of course, I got the usual grounding that many receive from their mothers and grandmothers and from the societal expectation that being in possession of mammaries and ovaries should lead inevitably to being in charge of cooking dinner.

I’ve wondered, ‘Why am I doing this?’ Why am I sacrificing my social life (I never go out from Thursday to Sunday nowadays), my living room (life is lived in my bedroom, the living parts of the flat have shrunk to bedsit proportions), my mental health (my daughter says my personality totally changes every weekend; I turn into a stressed-out monster).

But then something like this happens...

One evening, from the kitchen, I heard a glass being clinked in the living room, then quiet. Somebody was speaking seemingly to the entire room.

Agog, I sneaked out to have a look. A young woman was standing up, introducing herself and saying, ‘It’s such a nice atmosphere here and I’d like to know more about the other tables so, if you like, perhaps you could say who you are, what brought you here...’

There was a little silence, then one by one, people started to stand up and say their names, where they came from, how they had heard about The Underground Restaurant.

This display of ‘show and tell’ was fantastic. It was also a little weird, like an intervention or a 12-step programme entitled ‘Supper-club addicts anonymous’. People were participating, contributing and using the space and the occasion in an unusual way. There was a lot of love in the room.

I’ve cooked at anti-G8 camps, catering for ‘barrios’ of 250 activists using local ingredients and whatever ‘The Anarchist Teapot’ catering company got delivered. Our materials were dumpster-dived; once, needing an enormous spoon to stir a large pot, we used a cricket bat instead. I’ve cooked in Belgrade for the People’s Global Action conference. Ever fed 450 hungry Serbian trade unionists, German punks and French philosophers? I have.

I cooked at a co-operative vegan cafe in Hackney, whose principles are as strong as their customers are random. It is in Crackney after all. I cooked weekly at the appropriately acronymed R.A.G., the Radical Anthropology Group, an evening class of anthropologists who mostly discuss the moon, Stonehenge, periods and Marxist sex strikes in hunter-gatherer societies. I’ve cooked at festivals, in fields, while the rest of the staff were high on E and K. I’ve cooked in squats, one of which was in a swimming pool, where I lived with my boyfriend in a changing room. I’ve cooked cans of soup on my car engine, on the way to camping. I pulled mussels from the freezing Antarctic sea, having backpacked to a national park in Tierra Del Fuego carrying white wine and garlic in my pockets to make moules marini?res. I’ve dug clams at low tide on the Ile de R? to make a campfire Spaghetti Vongole. I’ve cooked from a tiny cramped ‘vis ? vis’ apartment in Paris, on a two-ring camping gaz stove, watching my neighbour’s every movement, the routine of ‘metro, boulot, dodo’(train/work/sleep). I cooked for the fortieth birthday of a man that had just dumped me. Heartbroken, humiliated, I made sure that there was a great spread, for him and his new girlfriend. Cooking is therapy.

In the last two years, since I started The Underground Restaurant, so many things have happened. I’ve had problems with trademarks, my freeholder, and Warner Brothers (the latter because I hosted a Harry Potter-themed dinner serving Butterbeer).

All along, I have encouraged others to start up their own supper clubs, via a social-networking site (http://supperclubfangroup.ning.com/) where supper-club hosts can publicise their meals, chat to each other about problems, successes and suppliers. I’ve also recently started up a bakery from my house. There is a dearth of bakeries in the UK; every high street should have a good organic baker. The idea to start selling bread from my house came, again, from Latin America, when I stayed with a Chilean family after randomly meeting them at a countryside bus stop when I was travelling there. One morning, the man of the house started to bake bread, and I watched as he put a notice in his window, ‘Hay pan’ (There is bread). Gradually neighbours dropped by and bought hot buns from him.

‘I always make a larger batch when I bake, everybody does in the village, to sell to others,’ he told me.

It makes sense: your oven is heated, it doesn’t take much work to double or triple your recipe, plus you can earn a little money. In the old days in Britain, each street had a communal oven; people didn’t necessarily have their own. I have an Aga, a large and expensive bit of kit, which produces beautiful bread. My first attempt was nerve-wracking but very successful, although the notice in my window didn’t suffice – I had to go out on the street to collar passersby. I sold most of my bread, wrapped in brown paper, and met my neighbours. I’m assigning a regular day of the week to sell the bread now.

In 2010, I launched The Underground Farmers’ & Craft Market in my home and garden, a huge success with 40 stalls and 200 punters. The idea was to promote small businesses and local, urban and home-cooked food. As well as stalls, there were live cooking demonstrations: I showed how to bake focaccia, a porridge expert who had won a prize at The Golden Spurtle Championship showed how to make the perfect porridge, and an urban cheese maker from Peckham demonstrated how to make South-London Halloumi (#litres_trial_promo). We also had a cocktail bar on an ironing board and live music.

On another occasion, Marmite, manufacturers of my favourite spread, asked me to create recipes for Marmite cupcakes. They put my face on a jar of Marmite, a career highlight for me, the equivalent of winning a foodie Oscar! I was also asked to talk at the Women’s Institute and the Real Food Festival.

One question at the Women’s Institute did trip me up, however. A lady asked:

‘Do you mind it when other people use your toilet?’

For some reason I replied:

‘No. I’m not anal.’

I’m pretty sure this is the first time the word ‘anal’ has been used at a Women’s Institute lecture. And it’s true, I don’t mind when 200 strange bottoms use my loo. After all, I’ve been to India and Tibet.

A question people never ask: Why are you doing this?

Because I love to cook. Because I love to mother. Because I’m a feeder. Because I love to share. Because I like to be in control. Because I enjoy the potential for chaos. Because I’m lonely. Because I like to stir things up. Because I like causing trouble. Because I find it funny and it makes me laugh. Because I want to change things. Because it’s now my job, it’s my living. Because it makes me cook things I wouldn’t be bothered to try for just me and my daughter. Because I don’t have a big family. Because I love community. Because it’s fun to come up with an idea and make it happen. Because, although I love words, I like action even better.

How to Start Your Own Underground Restaurant

If you are a keen cook, a foodie or a traveller, you will probably, at some point, have dreamed about opening your own restaurant or caf?. People put their life savings into setting up a restaurant, but the reality is that around a third of all restaurants close within the first year. The long hours and small profit margins are tougher than you could ever imagine.

On the other hand, you may never have wanted a professional restaurant but simply adore cooking.

Or perhaps you are sick of inviting people to dinner, always being the host, spending a small fortune and never being invited back?

This chapter is for all of you…

So before you spend your money on buying a lease, hiring staff and equipping a professional kitchen, why not rehearse by starting a supper club? The main qualities you will need are friendliness, trust in others, faith, hospitality and a certain amount of bravery.

First of all, just do it. Go on, play restaurants. Take the plunge. It may even cure you of any urge to open a restaurant. I’m not going to hide the fact that it is a lot of work, you won’t make much money, you may even make a loss, but hell, it’s great fun. And believe me, you will never again go to a conventional restaurant with the same attitude. Suddenly all will become apparent: the mistakes, the cover-ups, the pressure and the sheer bloody slog of making food for large amounts of strangers.

Starting a supper club requires different rules to opening a restaurant. As a new phenomenon, the parameters are changing all the time. I will give you the benefit both of my experience and of the expertise of other underground restaurateurs.

So here is the 12-step programme:

1 LETTING PEOPLE KNOW................

Most guides on how to start your own restaurant focus on things like making sure your restaurant is in a good location and is obvious from the street, with effective ‘signage’. You don’t have that problem. The harder it is to find your supper club, the more obscure the location, the better. You will have no business from the street. Your clientele will come from word of mouth or word of mouse!

First of all, announce it. Tell your friends and family, and their friends and families. But you also want strangers, don’t you? Otherwise it’s just a dinner party with your mates. So you need to know how to pull in strangers. (Sounds like L’Auberge Rouge, a kind of hoteliers’ Sweeney Todd, doesn’t it?)

New media is your friend. Facebook, Twitter, blogging, Craigslist, Gumtree, Ning, these are all great methods for spreading the word. Start a Facebook group, set up a Twitter account, write a blog. By the time this book comes out there is bound to be some new fashionable social-media method, so find out what it is and use it. Age is no barrier to this: most of these media are user-friendly. Lynn Hill, who started the My Secret Tea Room near Leeds, is in her 60s and adept at making connections with new media.

But don’t forget old media: once you’ve found your feet, let your local newspaper know. You could even put ads up in newsagents and shops. (Sheen supper club did this, got a few snooty remarks but soon filled up with locals.) If you have a particular theme – say, organic seasonal food – then put up a little notice in your nearest organic produce shop.

Get cards printed; I get mine from MOO.com via Flickr. Easy-to-design, small and attractive. Personal marketing: every time you go out, take your cards with you, hand them out, explain your new venture. You could also get brochures done. Flypost, as if for a gig. All this is basic marketing and PR. You want to fill your places. Bums on seats.

Choose a name that is emblematic of your living-room restaurant. Most supper clubs use words like hidden, secret, underground or midnight in their name. This gives an indication of the clandestine and guerilla nature of the operation. Sometimes they call it after the location, such as The Shed or Ahoy there! (on a boat), or the menu served, like The Bruncheon club.

Best not to call the press until you’ve set foot in the kitchen. Go for a soft opening and practise your mistakes in private. (As one of the first, I did not have this advantage. The Guardian and several food bloggers insisted on coming for the first night even though I had explained that I probably wasn’t ready. It really added to the pressure. I had not foreseen the level of interest that my home restaurant would trigger.) However, it has not been PR expertise that got me publicity and renown: I’ve been making it all up as I go along, but I was excited about it, and that enthusiasm conveys itself to others…

It’s also a good idea to do some research. Go and visit other supper clubs. Read up on them if you are too far away to visit. Volunteer to help out for a night or two. I get e-mails all the time asking to work. Lady Grey of the Hidden Tea Room in London offered to take me to lunch to pick my brains. Feeding a cook is a perfect method of extracting information. You will soon work out what tricks and techniques you want to retain and which do not suit you. When I started, there were no others to check out. Now there are…so use them!

2 TAKING BOOKINGS................

Once you have people booking, you will need to work out a method for handling their enquiries. Do be courteous and answer all their e-mails within, say, a 24-hour period. If they have paid all or a portion up-front, remember that they don’t know you. If you don’t reply, they will get anxious, especially if you haven’t given them the address yet. I went to a supper club in Brighton that didn’t give me the address until the morning of the dinner. Anything could have happened, my e-mail could have gone down, I could have been staying the night elsewhere.

Another underground restaurateur didn’t give the address, only literary clues. It turned out she had a blue plaque of a well-known poet on the wall of her house. You could do a treasure hunt of clues, but while a little mystery is quite a good thing, don’t go over the top and exhaust your guests before they arrive!

So, bearing in mind that answering all these e-mails takes up a lot of time that you could be spending in the kitchen practising dishes, get yourself a system. Write a stock response, copy and paste it into each email. Have several replies ready:

1) I’m afraid we do not have space for that date blah blah but will put your name on a waiting list.

2) This is where to pay (bank details) or where to book tickets (web address).

3) Here is the address and time to come. How to get there, a map perhaps or transport directions. You may want to give them a phone number. But be wary of this unless you have someone to answer the phone for you. There’s nothing more annoying than last-minute phone calls from people who think nothing of pestering you endlessly with questions and requests for step-by-step directions to your doorstep. I’ve actually lost friends at my own parties by snarling at them when they called wanting to discuss their love lives, what they should wear etc., just as you are trying to organise everything and get your own make-up on.

4) Any house rules or information you might want to give.

5) Menus. I change them every week and post it up on my blog or on my Facebook group. But they are subject to change; the lack of choice is part of the appeal. You will eat what Mummy tells you!

At the beginning I would have, say, a group of four people booking and each of them would e-mail me twice. That’s eight e-mails for one group. Your head starts to explode and it can be a struggle to stay polite. Early on I had one guest who called me when I was in the bath. I tried to sound professional but he could hear the splashing. Eventually I confessed, ‘Well, this is a home restaurant, it’s not every day you get the chef taking reservations from his bath!’

If you have done a few dinners and want to continue, consider signing up with a ticket agency who will take the pressure off you and answer those e-mails. You will still get e-mails...from, say, people informing you of food allergies or birthdays, but not as many.

I forgot to give my address to one couple. My dinners start at 7.30 p.m. I was cooking all afternoon, but at 8 p.m. I just happened to check my e-mails. There were several desperate messages saying, ‘We’ve booked babysitting and we don’t know where you are! Please please call.’ I felt terrible. They did get here in the end and were rightly given a free bottle of wine.

So a website handling all that is rather a good idea. Unless you’ve got a huge amount of elves working for you for free.

3 PAYMENT.........................

Are you going to allow people to pay on the night? In cash? I knocked that idea on the head after the first week.

I had sold 15 places, the last two places booked only that afternoon. I was turning other people away. The last two people did not turn up! They had got drunk and could not be bothered. A supper club has no walk-in traffic. You need everybody to attend and pay. Profit margins, especially at the beginning, are so tight that you will, as I did, make a loss.

I had already spent the money on ingredients and increased the amount that I was cooking. Straight away I realised I needed a system of prepayment, or I would be losing money every week. One week, Horton Jupiter had ten no-shows. You can’t afford that. Nor do you want to live on the same leftovers for the rest of the week.

It’s not only the money: empty tables and spaces look bad, especially if it’s supposed to be a large mixed table and some people haven’t turned up.

Now in the confirmation e-mail I say: ‘Treat this like an invitation to a friend’s dinner party. If you can’t come, at least let the hostess know.’

So my advice is to at least take a deposit, if not to get them to pay the full amount beforehand. You can go two routes with this: they can pay directly into your bank account, in which case you are revealing your name and address. If you do not want to do that, they can pay via Paypal or a ticket seller. I started with Paypal, but I still had to respond to e-mails and their customer service is abroad. Also, let’s face it, it is a multi-national company, and part of the underground-restaurant movement’s ethos is that you are sticking it to The Man. Why sign up with a globalised corporation? It’s everything we are against.

I went with a British ticket seller: wegottickets.com. They charge ten per cent on top, to the customer not to you. There are other ticket sellers too, like brownpaper tickets, but I haven’t tried them.

You have to remember that this is still a new thing for many people. They can be quite nervous about coming and need reassurance. A ticket agency is, hopefully, reputable and gives the added guarantee that should something go wrong, the customers have a third party to complain to, get their money back from.

A good ticket agency will quickly deal with e-mails, bookings, and have English-speaking customer service. The only disadvantage is that, under British law, they will be the ones who have the mailing list, not you, and it’s an opt-in list. You need to build your mailing list for future events, so I suggest that you get a visitors’ book where people can write their comments, e-mail addresses and Twitter IDs. Or come to an arrangement with the ticket seller.

DECIDE YOUR PRICE.........................

Find out what local conventional restaurants are charging. That’s a good guideline.

While many people expect to pay less at a home restaurant – after all, you are not paying business rates and rents – at the same time you are not getting the bulk discounts and trade prices that conventional restaurants benefit from. Also, if they don’t sell a dish one night, they can sometimes sell it the next.

But remember that you are offering a unique experience that restaurants cannot offer. Don’t undersell yourself. It’s a tough balance.

Work out what you are comfortable with and stick to it. The rule is a third of your income should get used for expenditure on ingredients; a third on staff, laundry, equipment, utilities, bills, everything else; and the remaining third is profit. You probably won’t make a profit at first. In your anxiety to please, you may overspend on ingredients, buy new furniture and all sorts of equipment.

Decide on your policy about free places. I don’t give any free places except to my mother. My friends pay. The press pays. I can’t afford to give away free seats. I run a tiny little operation.

You could give discounts to friends if you like, or people could volunteer to work in exchange for dinner. I save places at cheaper rates for the unemployed. I do this for a couple of reasons: I’ve been a single mother for many years, living on very little money. I have a great deal of understanding of what it feels like to be left out of something because you simply can’t afford it. Plus I’m political, idealistic. I want the world to be a better place. That may sound mawkish but it’s true.

4 LOCATION................

As I said before, you have an advantage over a conventional restaurant. It doesn’t really matter where you are located. People are, in effect, ‘invited guests’ and you are not depending on footfall in the vicinity. In some ways, just like at the peak of the rave culture, the more obscure the location, the more exciting it is for the guests.

Are you going to have it in your home or a pop-up location? It’s easier logistically to have it at home, especially if the pop-up location doesn’t have a kitchen. You don’t have to transport all the cooking utensils, plates, silverware and ingredients to the new place.

There are plenty of locations to host pop-up restaurants: ask for the use of a caf? that is open only at lunchtimes and would be happy to get a little rent for the evenings, or one that is normally closed at weekends. Do a deal with a pub, ask to use their function room while they provide the drink. This would avoid licensing problems. Other ideas for locations: an art gallery, a squat, a loft, a boat, a factory, a garden or allotment if the weather is good.

Personally I prefer it in the home. Part of the excitement is the voyeurism of going into someone’s private space. I love looking at people’s houses.

It’s true however that this takes a certain amount of bravery; where you live, how you live, your cooking, perhaps even your family life, is exposed to public view and possibly public criticism. But, people are aware of that and are always – so far, in any case – very polite. To your face at least. Who knows what they say on the car ride home? But they don’t expect restaurant-level cooking and a spotless, luxury location. The kind of people who book will be adventurous, curious and flexible. They just want something authentic and some proper home cooking.

So, banishing any insecurities, think about your space, where you live, where people are going to eat. Play to its strengths...do you have a big balcony or garden? Have the drinks on the balcony, or use it for barbecue cooking. Is there something quirky or unusual about the design of your place? Do you have a large or particularly nice kitchen? Make sure you invite people to have a look.

Where are people going to eat? The likelihood is that your living room is the largest room. I had to move first one, then the other sofa into my bedroom, then the TV, then everything else. My bedroom, formerly a luxury boudoir, designed to ensnare men, now looks like a junkshop.

The look: part of the charm of a supper club is your personal style...whatever it may be. I lived for six years in Paris and one year in Provence (a clich?, but true) and I’ve been collecting vintage crockery and French kitchenalia for years, so that is part of my style, shabby chic Francophilia.

You may prefer a more modern and clean look. A friend of mine, originally from Zimbabwe, has only wooden crockery and bowls, much of it African. Her flat is like going into a little forest, full of birds’ nests and chunks of tree trunk.

If you haven’t got much money, you might go to Ikea, or your local second-hand and charity shops. Freecycle and eBay are also options for free/cheap furniture and crockery. I’ve been to squats where you drink out of jam jars rather than glasses, it was fun!

It’s about vaunting your style…you may love heavy, hand-made pottery, slate platters, silver cloches or Toby Jugs. Even if you have no style or very bad taste, that too can be part of the experience. If you are in a large city and there are several supper clubs, you will find that people will do the circuit, come around to see you all, and they want each one to be different.

The individuality of the place and the table settings is part of the appeal. The quirkiness, the individuality, the absence of corporate tableware, all this is key to the success of a home restaurant.

There are some supper clubs that imitate restaurants. You book a table for two, you don’t talk to other tables. You have imitation restaurant food. The portions are tiny, nouvelle-cuisine restaurant stylee. You aren’t invited into the kitchen and all signs of slovenly family life have been tucked away. The service is formal, even obsequious. The china matches, and has been bought especially for the occasion.

I don’t get it. This is our chance to muck about with the format. Frankly, if I feel like serving a dozen starters and no pud, or vice versa, well why not? Let’s play. Yes, one has to give some food, there has to be some kind of chef/dinner/guest equation, but let’s push it around a little. ‘Guests’ can help out, come into the kitchen, get their own water. They keep their cutlery between courses, just like in France. ‘Staff’ can sit down and chat. The hierarchy is horizontal. It’s anarchy, but in the true sense of the word: ‘an’ (Greek for ‘without’) ‘archy’ (a ruler). Not chaos.

Remember: you are not a proper restaurant; you don’t have to pretend to be one. At first you will probably try to ape a restaurant – after all, this is the model that we know. But afterwards, as you gain confidence, tear up the rulebook!

Work out how many tables and chairs you have. Borrow from neighbours and relatives. (I went to one supper club that was allowed to borrow neighbour’s chairs only until midnight! Like Cinderella we had to sit on the floor afterwards!) You could also buy some cheap fold-down ones, depending on the look you want. You can always paint them, add nice cushions. Chairs, crockery, glasses and cutlery do not have to match: mismatching is great if everything ‘shouts’ at the same volume.

If you don’t have enough chairs, and the guests live nearby or have a car, let them bring their own. (Two girls once brought their own chairs to my place, then went out partying later, carrying them to a nightclub. They told me it was very handy for sitting down in the club later, not to mention a great conversation starter.) I have also used piano stools, drum stools, boxes, dressing-table stools.

The tables you buy, borrow or retrieve from the garden will guide whether you put your guests on small tables with separate parties or large mixed tables.

As for the bathroom, label it and signpost it so that people know where to go. Make sure it’s clean. Always have enough loo paper. A clean towel to dry their hands is good. After several weeks during which I kept having to buy more ear buds, I realised they were being used by the guests! I think conventional restaurants are missing a trick by not providing them! You could really go to town and provide eau de cologne, hairspray and lipstick as they do in the bathrooms of New York nightclubs.

5 FOOD.........................

Obviously this is the most important element. The menu is at the heart of what you are creating.

WHAT ARE YOU GOING TO COOK?.........................

The first few times, I’d stick to the dishes you are most comfortable with cooking. You will be nervous enough, you don’t want to cock up the cooking! Later on, you can let rip with the molecular experiments!

Leave enough time to prep, and for mistakes. In your anxious state, it’s amazing how dishes you’ve cooked perfectly a hundred times can go wrong. If you do decide to experiment, practise it first. Also remember that a dish that works wonderfully for 2–6 people is very different when you are doing it for double or more than that amount of people.

The secret of good food is: spend less time cooking and more time shopping! Unusual and seasonal ingredients, even just to garnish, can add that extra flair. This is what I do, but how you do it is up to you.

~ Cocktail with olives, pretzels or nuts ~

~ Starter ~

~ Home-made bread ~

~ Main course ~

~ Salad ~

~ Cheeseboard ~

~ Dessert ~

~ Coffee ~

(sometimes fresh mint tea, depending on the meal)

For ?40 that’s not bad value. The point is, you can afford the whole experience. In conventional restaurants, a lot of mental arithmetic is involved, trying to figure out if you should share a starter, miss out pudding, have coffee at home. Those little bits really add up and that is how normal restaurants make their money, with the drink, the desserts and the coffees…in short, the extras. It can make dining a frustrating experience. Even when restaurants do fixed menus, frequently there are ‘supplements’ that are added on, generally for the dish you really want.

Other times I have done tapas or meze, up to 12 small courses.

SUPPLIERS AND INGREDIENTS.........................

So you’ve made a shopping list. But how much to buy? Another difficulty. In a conventional restaurant, what you don’t sell one night, you can sell the next. For an occasional supper club you have to get it right. Only experience can tell you that.

And where are you going to buy, say, 30 artichokes for your starters? They cost a fortune in the supermarket. Suppliers are the bane of most restaurants. Reliable suppliers are the most important element of any business. If you do have connections to professional chefs or kitchens, ask them who their suppliers are...and whether they mind adding on an order for you. You will get better deals and normally they deliver to your doorstep. That’s a huge relief when prepping can take up so much time, and you don’t want to be popping out to the shops every 5 minutes.

My local organic vegetable box scheme guy came to a dinner. He loved the concept and will now do me bulk prices. It does take a while to build these relationships but they are invaluable. Repay favours in kind, invite them to a dinner!

I do a mix of shopping between the local organic veg supplier and my local street markets. Going to a street market can be very inspirational when you are feeling a bit flat, a bit ‘What the hell shall I cook this week?’

Use good ingredients. Don’t skimp on quality. If your ingredients are good, you can’t go too far wrong. One supper club I read about didn’t cook anything. They just ordered great cheeses, hams, salamis, bread, salads, chutneys, smoked fish and set it out picnic-style.

If you or your friends have gardens or allotments, ask them to sell you their excess.

I do buy from large multi-national supermarkets sometimes. It’s convenient and they deliver, saving time for you. But I try not to do so. I feel this whole ‘movement’ is about circumventing large-scale corporations.

PLAN YOUR MENU.........................

Decide what kind of food, how many courses. When you know how many people you have coming, multiply whatever recipe you are doing to make that number of servings. Make a little extra. Many home restaurants do serve seconds, just like your mum would. Better to have more than less.