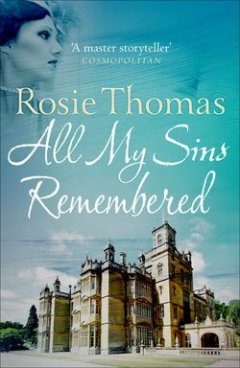

All My Sins Remembered

Àâòîð:Rosie Thomas

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:738.27 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 285

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 738.27 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

All My Sins Remembered

Rosie Thomas

From the bestselling author of The Kashmir Shawl. Available on ebook for the first time.Jake, Clio and Julius Hirsh and their cousin Lady Grace Stretton formed a charmed circle in those lost innocent days before the Great War – united against the world.Old now, Clio recounts their story for her biographer: Jake's wartime experiences, which moved him to work as a doctor in the London slums; Clio and Grace, flappers flitting through bohemian Fitzrovia to emerge as literary lion and pioneering Member of Parliament respectively; the music that drowned for Julius the crash of jackboots in thirties Berlin.But for herself, Clio remembers a different story. Desperate lies and bitter secrets, hopeless love and careless betrayal, jealous loyalties more like fetters. And above all, the truth about Grace, beautiful, destructive siren at the centre of the circle.

All My Sins Remembered

BY ROSIE THOMAS

Contents

Title Page (#u6c521e6f-dcdd-5f7b-92a5-88a271c335c4)

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Rosie Thomas

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

London, 1990

It was a lie, but it was not a lie that could do any damage.

The writer reflected on the relative harmlessness of what she was doing as she waited on the step for the doorbell to be answered. It was a cold and windy autumn afternoon, and the trees that bordered the canal in Little Venice were shedding their leaves into the water. She had turned away to look at the play of light in the ripples drawn behind a barge when the door opened at last behind her.

There was a smiling nurse in a blue dress. ‘Mrs Ainger, hello there. Come in, now.’

‘How is she today?’ Elizabeth Ainger asked.

‘Not so bad at all. Quite clear in the head, as a matter of fact. She even asked when you were coming.’

‘She’s getting used to me,’ the biographer said. ‘I’m glad it’s one of her good days.’

The nurse showed her into a drawing room at the rear of the house with a view of a small garden through double doors. There were porcelain ornaments arranged on the marble mantelpiece, a little blue painting of an interior hanging above them, embroidered cushions and faded rose-patterned loose covers. These neat, traditional furnishings were faintly at odds with the picture that hung on the wall behind the old lady’s chair. It was a double portrait, in oils, of two young women. They were looking away from each other, out of the frame of the picture, and there was tension in every line of their bodies. The painter’s peculiarly hectic style owed something to Picasso, and something to Stanley Spencer.

It was so quiet in the room, away from the noise of the traffic, that the occupant might have been sitting in some cottage in the country instead of in the middle of London.

‘Hello, Aunt Clio,’ Elizabeth said. The nurse withdrew, and closed the door behind her.

The tiny old woman in the velvet-upholstered chair was not really Elizabeth’s aunt, but her grandmother’s first cousin. But it was to ‘Aunt Clio’s’ house in Oxford that Elizabeth had been taken on visits with her mother when she was a little girl. She could just remember the rooms, with their forbidding shelves of dark books, and her childish impression that Aunt Clio was important, but in some way not easy.

When Elizabeth was seven, her American father had taken his wife and daughter back to live in Oregon, and there had only been birthday cards and Christmas presents from Oxford after that. By the time Elizabeth was grown up herself, and had come back to live in the country of her birth, the links had been all but broken. Until this series of visits had begun, the two women had not met for thirty years.

Clio turned her head a fraction to look at her visitor. ‘It’s you, is it?’

Elizabeth smiled and shrugged, deprecatingly held out her tape-recorder.

‘I am afraid so. Do you feel too tired to talk today?’

‘I am not in the least tired.’

She did not look it, either. Her body was tiny and frail, but her eyes were bright and sharp like fish caught in their nets of wrinkles. She watched Elizabeth Ainger sitting down, adopting a familiar position in the chair opposite to her own, and fiddling with her little tape-recorder.

‘I just wonder why you are not bored to death with all these old tales?’

With a show of cheerful patience the younger woman answered, ‘You can’t tell me anything that will bore me. I am your biographer, remember?’

That was the lie, but it came out fluently enough.

The biography was not of her relative, Clio Hirsh, although she would not have been an inappropriate subject, but of Clio’s first cousin.

Lady Grace Brock, n?e Stretton, was Elizabeth’s maternal grand-mother. She was the daughter of an Earl, a famous socialite in her day and then one of the first women Members of Parliament.

Elizabeth had never met her, but she was fascinated by her. And her enthusiasm had communicated itself to her publisher when they had met to discuss over lunch what Elizabeth’s next project might be as a middle-range, moderately successful author of popular biographies.

‘Diana Cooper and Nancy Cunard did well enough,’ the published mused. ‘Although your grandmother is not quite so well known, of course. Why don’t you put some material together for us to have a look at?’

Elizabeth’s mother and the rest of the family had warned her at the outset that Clio was famously reluctant to talk about her cousin and friend. The defences that the old lady duly put up against Elizabeth’s first casual enquiries were infuriating, and impregnable, but she needed her co-operation, and so Elizabeth had pretended that it was a family biography that she was researching, with particular emphasis on Clio’s own life.

Elizabeth was invited to call at the house in Little Venice. The first visit had led to a series of interviews, and Elizabeth had patiently waited and listened.

It would not matter if the finished book was not what had been promised. Books took a long time to write, and Clio was very old and no longer reliably clear in her own mind.

Clio said irritably, ‘I bore myself. Who could possibly want to read anything about me? I wish I hadn’t agreed to this rigmarole.’

‘But you did agree.’

‘I know that. And having agreed to it, I am doing it.’ She was tart, as she often was on her lucid days. Elizabeth knew that Clio did not care for her, but she took the trouble to conceal her own reciprocal irritation.

‘We were talking about Blanche and Eleanor, last time I was here,’ Elizabeth prompted.

‘You know it all. You’ve seen all their letters, the papers. What more do you want to hear?’

‘Just what you remember. Only that.’

The old woman sighed. She was almost ninety. She remembered so many things but she had forgotten more. The firm connective tissue of memory that once held the flesh of her life together had all but dissolved. There were only incidents to recall now, isolated like the tips of submerged rocks rearing out of a wide sea.

Then, in a stronger voice, Clio suddenly said, ‘I remember my Aunt Blanche’s scent. White lilac, and burnt hair. They frizzed their hair, you know, in those days. With curling tongs that the maid heated red-hot in the fire. I remember the smell of burning hair.’

Elizabeth pressed the record button, and then sat quietly, listening as Clio talked. This was the pattern of her visits.

One (#u2bf208d7-2a0d-5ee2-b00e-16756161e98b)

The old woman sat propped in her nest of cushions and rugs. Her hands rested like small ivory carvings on the rubbed velvet arms of the chair. The visitor waited, watching her to see if she would doze, or sit in silence, or if today would be a talking day.

Clio said to Elizabeth, not looking at her but away somewhere else, a long way off, ‘I remember the holidays. There were always wonderful holidays.’ She tilted her head, listening to something that reminded her.

When she thought about it, she supposed that had been Nathaniel’s doing. Nathaniel applied the same principles to holidays as to his work. He could turn the radiance of his enthusiasm equally on the business of enjoyment or the pleasures of academic discipline. And Nathaniel’s enthusiasm infected them all, all of his children. When the time came for the family migrations, excitement would fill the red-brick house with high-pitched twittering, like real birds. Clio could hear the starlings out in the garden now. It must be their chorus that had taken her back. The nurse would have tipped the crusts of the breakfast toast on the bird-table.

‘Where did you go?’ Cressida’s daughter Elizabeth asked.

‘Different places.’ Clio glanced at her, suddenly sly. ‘Grace and the others used to come with us, too.’ It amused her to see how the mention of Grace sharpened the other’s attention. It always did.

There had been different holidays, but almost always beside the sea. They would take a house, or two houses, if one was not big enough for Hirshes and Strettons together, with their retinue of nursemaids and attendants. The children and their mothers would stay there all the long summer, and the two fathers would visit when they could.

Only they almost never came at the same time. Nathaniel would go away for some of those summer vacations on reading parties with his undergraduates, or on visits to Paris and Berlin. And John Leominster had the estate at Stretton to attend to, and business in London, and the affairs of his club.

It was Blanche and Eleanor who were always there.

Clio and Grace and the boys ran over the expanses of rawly glittering sand, or hung over the rock pools, or dragged their shrimping nets through fringes of seaweed before lifting them in arcs of diamond spray to examine the catch. It was the mothers they always ran back to, to show off the mollusc or sidling crab, Jake pounding ahead with Julius at his heels, and shoulder to shoulder, the two girls, with their skirts gathered up in one hand and their sharp elbows sticking out. If one of them could manage a dig at the other, to make her swerve or miss her footing, then so much the better. It would mean reaching the boys first, having the chance to blurt out with them the news of the tiny discovery, while the loser came sulkily behind, forced to pretend that nothing mattered less.

The two nannies sat with the nursemaid in a sheltered corner at the top of the beach. The little brothers and sisters, Hirshes and Strettons, played at their feet or slept in their perambulators. These babies were beneath the attention of the bigger children. The flying feet swept past, sending up small plumes of silvery sand, heading for the mothers.

Blanche and Eleanor sat a little distance apart, beneath a complicated canvas awning. They were protected from the sun and the sea breeze by panels of canvas that unrolled from the roof-edge. The little pavilion was carried down to the beach every morning and erected by Blanche’s chauffeur, who also brought down their canvas chairs and spread out the rugs on which they rested their feet. One year Hugo Stretton had made a red knight’s pennant to fly from the top of the supporting pole. This spot of scarlet was the focus of the beach, however far the children wandered. The twin sisters sat beneath it in the canvas shade, watching their families and mildly gossiping. Sometimes there was a husband nearby, either Nathaniel Hirsh, with his black beard bristling over a book, or John Leominster, bowling at Hugo who stood in front of a makeshift wicket and squinted fiercely at the spinning ball. But if neither husband was there, Blanche and Eleanor were equally content. They found one another’s company perfectly satisfactory, as they had always done.

It was always Jake who reached them first.

‘Look at this, Mama, Aunt Blanche. Look what we found.’

Then Julius would plunge down into the sand beside him. ‘I found it. It came up in my net.’

And one of the girls would drop between the two of them, panting for breath and grinning in her triumph. ‘Isn’t it beautiful? Can we keep it for a pet? I’ll look after it, I promise I will.’

The second girl would stumble up, red-faced and pouting. ‘Don’t be silly, you can’t keep things like that for pets. They aren’t domestic,’ Clio would say scornfully, because it was the only option left open to her. It was usually Clio. Grace was quicker and more determined in getting what she wanted. She usually won the races. It isn’t fair, Clio had thought, almost from the time she had been able to think. Jake is my brother and Julius is my twin. They’re both mine, Grace is only an outsider.

But Grace never behaved like an outsider, and never behaved as if she owed her Hirsh cousins any thanks for her inclusion in their magic circle. She took it loftily, as her right.

The children knelt in a ring, at their mothers’ feet. Jake put his hand into the net and lifted out their catch to show it off. Blanche and Eleanor bent their identical calm faces and padded coiffures over him, ready to admire.

One of them gave a faint cry. ‘It is quite a big one. Don’t let it nip you, Jacob, will you?’

Hugo was digging in the sand nearby. His curiosity at last overcame him and he left his complicated layout of moats and battlements and strolled over to them, his hands in the pockets of his knickerbockers.

‘It’s only a stupid crab,’ he observed.

‘Stupid yourself,’ Clio and Grace rounded on him, united in defence. ‘Just because you didn’t catch it.’

‘I wouldn’t have bothered. It’ll die in five minutes, in this sun.’

Hugo turned his back on them, returning to his solitary game. Hugo was Grace’s elder brother. He was good as an extra player in field games, or for Racing Demon, or to perform the less coveted roles in the rambling plays that Clio and Julius wrote, but he never belonged to the circle. There was room for only the four of them within it.

Hugo would have said, ‘I’m not interested in stupid clubs. They’re for little girls.’

Knowing better, none of them would have bothered to contradict him.

Eleanor or Blanche would say, soothingly, ‘It is very handsome. Look at those claws. But I think Hugo may be right, you know. It will be happier under a rock, somewhere near the water. Shall I walk over there with you, so we can make sure it finds a safe home?’

Then, whichever mother it happened to be would stand up, smoothing the folds of her narrow bell skirt and the tucked and pearl-buttoned front of her white blouse. If it was a hot day she would shake out the folds of her little parasol and tilt it over her dark head, before following them across the shimmering sand. The hem of her skirt trailed on it, giving a rhythmic, languid whisper. The mothers’ feet were always invisible, even beside the sea. Even though she knew Blanche really wore elegant narrow shoes in suede or glac? kid, Grace used to imagine that her mother’s gliding step was the result of wheels, smoothly revolving beneath her rustling gowns.

When they came to the rocks the children hunched together, watching as Jake slowly opened his hands and laid the crab in the narrow slice of shade. The creature seemed to rise on its toes, like a ballerina on points, before it darted sideways. They watched until the crimped edge of the green and black shell disappeared under the ledge. Julius flattened himself on his stomach and peered after it, but he couldn’t see the stalky eyes looking out at him.

‘It’s gone,’ they said sadly.

The mother or aunt reassured them. ‘It will be happier, you know. A crab isn’t like the dogs, or Grace’s rabbits.’ And, seeing their miserable faces, she would laugh her pretty silvery laugh, and tell them to run over to Nanny and ask if they might walk to the wooden kiosk at the end of the beach road for lemonade.

When was that? Clio asked herself. Which summer, of all those summers? Grace and Julius and I must have been nine, and Jake eleven.

Nineteen ten.

And where?

It might have been Cromer, or Hunstanton. Not France, that was certain, although there had been two summers on the wide beaches of the Normandy coast. That had been Nathaniel’s doing, too. He had made the plans, and chosen the solid hotels with faded sun awnings and ancient, slow-footed waiters. He had supervised the exodus of the families, marshalling porters to convey brass-bound trunks, seemingly dozens of them, and booming instructions in rapid French to douaniers and drivers. It had all seemed very exotic. Clio was proud of her big, red-mouthed, polyglot father. Uncle John Leominster seemed a dry stick beside him, and Clio glanced sidelong at Grace to make sure that she too was registering the contrast.

But if Grace noticed anything, she gave no sign of it. She would look airily around her, interested but not impressed. Her own father was the Earl of Leominster, milord anglais, and she herself was Lady Grace Stretton. That was superiority enough. Clio writhed under the injustice of it, her pride in Nathaniel momentarily forgotten. That was how it was.

Eleanor and Blanche enjoyed Trouville. They liked the early evening promenade when French families walked out in chattering groups, airing their fashionable clothes. The Hirshes and Strettons joined the pageant, the sisters shrewdly appraising the latest styles. The Countess of Leominster might buy her gowns in Paris but Eleanor, a don’s wife, couldn’t hope to. She would take the news back to her dressmaker in Oxford.

The two of them drew glances wherever they went. They were an arresting sight, gliding together in their pongee or tussore silks, their identical faces framed by huge hats festooned with drooping masses of flowers or feathers. Their children walked more stiffly, constrained by their holiday best, under the benign eye of whichever husband happened to be present. Grace liked to walk with Jake, which left Julius and Clio together. Clio was happy enough with that, but she would have preferred it if Jake could have been at her other side.

They were all happy, except for Uncle John, who did not care for Abroad. Blanche never wanted to oppose him, and so the experiment was only repeated once. After that, they returned to Norfolk.

Nineteen eleven was the year of the boat.

The summer holiday began the same way as all the others. The Hirshes and their nanny and two maids travelled from Oxford to London by train, and stayed the night in the Strettons’ town house in Belgrave Square. It was an exciting reunion for the cousins, who had not seen each other since the Easter holiday at Stretton. Clio and Grace hugged each other, and then Grace kissed Jake and Julius in turn, shy kisses with her eyes hidden by her eyelashes, making the boys blush a little. Hugo watched from a safe distance. He was already at Eton, and considered himself grown up. The other four sat on the beds in the night nursery, locking their circle tight again after the long separation.

The next day, the two families set off by train from Liverpool Street station. There were three reserved compartments. The parents travelled in one, the children and nannies in another, and the maids in the third. The nannies pinned big white sheets over the seats, so the childrens’ hair and clothes didn’t touch them.

‘You never know who else has been sitting there before you, Miss Clio,’ Nanny Cooper said, compressing her lips. They ate their lunch out of a big wicker picnic basket, and afterwards the smaller children fell asleep. Tabitha Hirsh, the youngest, was still a tiny baby.

At the station at the other end, the Leominster chauffeur was waiting to meet them. He had driven up from London with part of the luggage.

That year, there was one big house overlooking the sea. It was a maze of rooms opening out of each other, with a glassed-in sun room to one side that smelt of dried seaweed and rubber overshoes. The children ran through the rooms, shouting their discoveries to each other while the maids and nannies unpacked.

Later, in the early evening, there was the first scramble down on to the beach. The clean air was full of salt and the cries of gulls. Nathaniel put on his panama hat and went with the children, letting them run ahead to the water’s edge and not calling them back to walk properly as the nannies would have done. From the high-water mark, where the girls hesitated in fear of wetting their white shoes, they looked back and saw Nathaniel talking to a fisherman.

‘What’s he doing?’ Julius called. ‘Can we go fishing?’

When he rejoined them, Nathaniel was beaming. ‘Surprise,’ he announced, waving his big hands. The children surged around him.

‘What is it? What?’

‘Look and see.’

They followed him across the sand. There was an outcrop of rock draped with pungent bladder wrack, and an iron ring was let into the rock. A rusty stain bled beneath it. A length of rope was hitched through the ring, and the other end of it was secured to a small blue dinghy beached on the sand. A herring gull perched briefly on the boat’s prow, and then lifted away again.

Grace stooped to read the faded lettering. ‘It’s called the Mabel.’

‘Your Mabel, for the summer,’ Nathaniel told her.

‘Ours? Our own?’

‘I’ll teach you to row.’

Hugo was already fumbling with the rope. ‘I can row.’

Nathaniel and the fisherman eased the dinghy down to the water’s edge, steadying it when the keel lifted free and bobbed on the ripples.

‘Six of us. You’ll have to sit still. Hugo in the front there, Jake and Julius in the middle. Leave room for the oarsmen. The girls at the stern.’ He ordered them fluently, and they scrambled to his directions, even Hugo. The fisherman in his tall rubber waders lifted Clio and swung her over the little gulf of water.

‘There, miss. Now your sister’s turn.’ He went back for Grace, and hoisted her too.

‘She’s my cousin, not my sister,’ Clio told him quickly.

‘Is that so? She’s like enough to be your twin.’

‘He’s my real twin,’ Clio pointed at Julius.

‘But he’s nothing like so pretty,’ the man twinkled at her. Clio was sufficiently disarmed by the compliment to forget the mistake. Nathaniel dipped the oars, and the Mabel slid forward over the lazy swell.

There had been boat rides before, but none had seemed as magical as the first trip in their own Mabel. They bobbed out over the green water, into the realm of the gulls. Only a few yards separated them from the prosaic shore, but they felt part of another world. They could look back at the old one, at the holiday house diminished by blue distance and at the white speck of a nanny’s apron passing in front of it. Out here there were the cork markers of lobster pots, a painted buoy with another gull perching on it, and the depths of the mysterious water.

Grace leant to one side so that her fingers dipped into the waves. She sighed with pleasure. It was the first day of the holidays. There were six whole weeks to enjoy before she would be returned to Miss Alcott and the tedium of the schoolroom at Stretton. Jake and Julius were here. She was happy.

Nathaniel bent over the oars. The dinghy skimmed along, and the sea breeze blew the railway fumes out of their heads.

Jake said, ‘I can see Aunt Blanche. I think she’s waving.’

Nathaniel laughed. He had a big, noisy laugh. ‘I’m sure she’s waving. It’s our signal to make for dry land.’

He paddled vigorously with one oar and the boat swung in a circle. When it was broadside to the sea a wave larger than the others slapped against the side and sprayed over them. The girls shrieked with delight and shook out the skirts of their white dresses.

‘Rules of the sea,’ Nathaniel boomed, as the Mabel rose on the crest of the next wave and swept towards the beach.

The rules were that no child was allowed to take out the dinghy without an adult watching. The girls were not allowed to row unless one of the fathers came in the boat. The boys would be permitted to row themselves, once they had passed a swimming test that would be set by Nathaniel.

The boys often bathed in the summer holidays, wearing long navy-blue woollen bathing suits that buttoned on the shoulders. To their disappointment the girls were not allowed to do the same, because Blanche and Eleanor had never done so and didn’t consider it desirable for their daughters. They had to content themselves with removing their shoes and long stockings and paddling in the shallows.

‘Are the rules understood?’ Nathaniel demanded ferociously.

‘We understand,’ they answered in unison.

The keel of the dinghy ran into the sand like a spoon digging into sugar. The fisherman had gone home. The boys jumped ashore, Nathaniel lifted Clio and Grace launched herself into Jake’s arms. He staggered a little with the weight of her, and a wave ran up and licked over his shoes.

They all laughed, even Clio.

As they trudged back up to the house Grace said to Clio, ‘I must say, I think your father can be splendid sometimes.’

‘So do I,’ Clio answered with pride.

The days of the holiday slipped by, as they always did.

John Leominster was in Scotland for the shooting. Nathaniel went away to London, then came back again. Blanche and Eleanor stayed put, happy to be together, as they had been since babyhood. They wrote their letters side by side in the morning room, walked together in the afternoons, took tea with their children when they came in from the beach and listened to the news of the day, and after they had changed in the evenings they ate dinner alone together in the candlelit dining room, the food served to them by the manservant who came from Stretton for the holiday.

The children, from elsewhere in the house, could often hear the sound of their laughter. Clio and Grace listened, their admiration touched with resentment at their own exclusion. They knew that the two of them could never be so tranquil alone together, without Jake, without Julius.

For the children there were races on the beach, picnics and drives and hunts for cowrie shells, and, that year, rowing in the Mabel. The boys passed their swimming tests, and became confident oarsmen. They learnt to dive from the dinghy, shouting to each other as they balanced precariously and then launched themselves, setting the little boat wildly rocking. The girls could only watch enviously from the waterline, listening to the splashes and spluttering.

‘I could swim if they would just let me try,’ Grace muttered.

‘And so could I, easily,’ Clio affirmed. ‘Why isn’t Pappy here, so that we could at least go in the boat with them?’

They weren’t looking at each other when Grace said, ‘We should go anyway. Prove we can, and then they’ll have no reason to stop us any more, will they?’

‘I don’t think we should. Not without asking.’

Grace laughed scornfully. ‘If we ask, we’ll be told no. Don’t you know anything about older people? Anyway, Jake won’t let anything happen.’

It was always Jake they looked to. Not Hugo, even though Hugo was the eldest.

‘I’m going to go,’ Grace announced. ‘You needn’t, if you’re scared.’

‘I never said I was scared.’

They did look at each other then. The fisherman had been right, they were alike as sisters. Not identical like their mothers, the resemblance was not as close as that, but they had the same straight noses and blue-grey eyes, and the same thick, dark hair springing back from high foreheads. When they looked they seemed to see themselves in mirror fashion, and neither of them had ever quite trusted the reflection.

Grace turned away first. She lifted her arm, and waved it in a wide arc over her head. The white sleeve of her middy-blouse fluttered like a truce signal.

‘Jake,’ she called. ‘Ja-ake, Julius, come here, won’t you?’

Jake’s black head, glistening wet like a seal’s, appeared alongside the dinghy. He rested his arms on the stern, hoisting the upper half of his body out of the water. He was almost thirteen. His shoulders were beginning to broaden noticeably under the blue woollen bathing suit.

‘What?’

Hugo and Julius bobbed up alongside him. Hugo’s head looked very blond and square alongside his cousins’.

Grace’s arm signal changed to a beckoning curl. ‘Come in to shore for a minute.’

Jake began lazily kicking. Julius and then Hugo dived and swam. Under Jake’s propulsion the Mabel drifted towards the beach. Clio thought, They always do what she wants. She turned to look up the sand. The two nannies were sitting as usual on a blanket on the lee of the sea-wall. Tabitha’s perambulator stood close by. The two younger Strettons, Thomas and Phoebe, were playing in the sand. They were turning sandcastles out of seawater-rusted tin buckets. Hills the chauffeur had put up the canvas awning ready for the mothers, but they had not come down yet. They would still be attending to their volumes of correspondence. Their empty steamer chairs sat side by side, and Hugo’s red pennant flew bravely above them in the stiffening breeze.

Clio saw the fisherman a little further up the beach. He was busy with his coils of nets.

When she looked behind her again it was to see the boys plunging through the shallows in sparkling jets of spray. Mabel rocked enticingly at the end of her painter.

‘It isn’t fair,’ she heard Grace saying. ‘You have all the fun in the boat. I think you should take me out now.’

‘Us,’ Clio insisted, and Grace looked at her but said nothing. She stood characteristically with her hands on her hips, her chin pushed out. Hugo laughed and Julius began to recite Nathaniel’s rules of the sea. Jake stood and looked at Grace, smiling a little.

Grace fixed on him. ‘There are grown-up people on the beach, the nannies and the fisherman. You three have been rowing and swimming all week. What difference will there be just in having us in the boat? And once we’ve been, they won’t be able to stop us going again, will they? The rules are petty and unfair.’

‘That’s true, at least.’ Support came from Hugo, who was never anxious to accept Nathaniel’s jurisdiction.

‘But we were told,’ Julius began.

‘Stay here with Clio, then.’

The twins shook their heads, and Grace smiled once more at Jake. ‘Wouldn’t it be fun for all of us to go out together, on our own?’

He put out his hand and took hers, making a little bow. ‘Will you step this way, my lady?’

Grace bobbed a curtsey, and hopped into the dinghy as Hugo held it. Her white cotton ankles twinkled under her skirts. Clio followed her, as quickly as she could. Julius sat in the prow and Hugo and Jake took an oar each. The rowlocks creaked and the Mabel turned out to sea. The nannies were still watching the babies.

It was exhilarating out beyond the breakers. The swell ran under the ribs of the dinghy, seeming to Clio like the undulations of breath in the flank of some vast animal. The waves looked bigger out here than they had done from the shore, but Hugo and Jake pulled confidently together and the boat rode over the wave-breaths like a cork. On the beach Nanny Brodribb suddenly stood up and ran forward, with her white apron moulded against her by the wind. She was calling, but none of the children heard her or looked round.

Grace let her head fall back. Her even teeth showed in a smile of elation. The satisfaction of getting her own way together with the sharp pleasure of the boat ride and Jake bending in front of her made her eyes bright and her cheeks rosy.

‘You see?’ she murmured. The question was for Clio, wedged beside her in the stern. ‘I was right, wasn’t I?’

They rowed on, turning in an arc away from the horizon, and once again a wave caught them broadside and washed in over them. This time, instead of laughing, Clio gave a small yelp of alarm. The water seeped in her lap, wetting her legs and thighs. It was surprisingly cold.

‘Don’t worry,’ Jake told her.

‘Don’t worry,’ Grace sang. She was filled with happiness, the sense of her own strength, after being confined on the beach with the women and the babies. She saw the blue sky riffled with thin clouds and wanted to reach it. It was joy and not bravado that made her scramble up to stand on the seat with her arms spread out.

Look at me.

They did look, all of them, turning their faces up slowly, as if frozen. All except for Clio, whose eyes were fixed on Grace’s feet planted on the rocking seat beside her wet skirts. She saw the button fastenings, and the rim of wet sand clinging to the leather. A second later the dinghy pitched violently. There was a wordless cry and the shoes flew upwards.

Jake shouted hoarsely, ‘Grace.’

Clio looked then. She heard the cry cut off and the terrible splash. She wrenched her head and saw the eruption of bubbles at the stern of the Mabel. Grace was gone, swallowed up by the sea. The boat was already drifting away from the swirling bubbles. It pitched again, almost capsizing as Jake and then Hugo launched themselves into the water. The boat began to spin helplessly. The sun seemed to have gone in, the brilliant morning to have turned dark.

‘Take an oar. Steady her,’ Julius screamed.

Clio was still staring into the water. In that instant she saw Grace, rising through it. Her face under the greenish skin of the sea was a pale oval, her eyes and mouth black holes of utter terror.

‘Row,’ Julius was shouting at her.

‘I don’t know how to,’ Clio was sobbing. She stumbled forward, took up the wooden oar, warm from Jake’s hands, and pulled on it.

Grace’s head had broken the surface. She was thrashing with her arms, but no sound came out of her mouth. Then she was sinking again, and Hugo and Jake ploughed on through the swell to try to reach her.

‘Pull with me,’ Julius instructed. Clio tried to harness her gasping fear into obeying him. She stared at his white knuckles on the other oar, dipped her own and drew it into her chest. Out, and then in again.

When she looked once more, Jake and Hugo had Grace’s body between them. She was lashing out at them with the last of her strength, her staring eyes sightless, and for a long moment it seemed that all three of them would be submerged. A wave poured over them, filling Grace’s open mouth. Jake flung back his head, kicking towards the Mabel and trying to haul her dead weight with him. She hung motionless now with her head under the water.

Julius rowed, and Clio battled to keep time with him. Her teeth chattered with cold and terror and she repeated over and over in her head, Help us, God. Help us, God.

The gap narrowed between the boat and the heavy mass in the water. Hugo had his arm under Grace’s shoulders. ‘Come on,’ Julius muttered. On the beach the two nannies had run to the water’s edge. Their thin cries sounded like the seagulls. Julius saw too that the fisherman had shoved out in his much bigger boat, the one he used to row around the lobster pots. The high red-painted prow surged through the breakers.

Hugo and Julius were closer. Grace was between them, a tangled mass of hair and clothes and blanched skin.

‘Ship your oar,’ Julius ordered Clio. He leaned over the side, tilting the boat dangerously again, stretching out his arms. His hand closed in Grace’s hair. He hauled at her, feeling the terrible weight, and another wave flung the dinghy upwards so that his oar rammed up into his armpit. Hugo was choking and flailing now, and Jake’s lips were drawn back from his teeth as he gasped for breath.

‘Hold her,’ he begged Julius. In spite of the pain Julius knotted his fingers in the sodden hair, and felt the body rise as Jake put his last effort into propelling Grace towards him. Between them, they forced one dripping arm and then the other over the dinghy’s side. Julius took another handful of the back of her dress and her head rolled, pressing her streaming cheek against the blue ribs of the Mabel. Jake and Hugo could do no more than cling on to the same side. Clio leant out the other way as far as she dared.

She was dazed to realize how far out to sea they had been carried. The beach and the headland and the houses seemed to belong to another world, a safe and warm and infinitely inviting place that she had never taken notice of until now, when it had gone beyond her reach. The words started up in her head again, Please God, help us.

The red prow of the fisherman’s boat reared over Jake, Hugo and Grace. The man lifted one oar and paddled with the other, manoeuvring the heavy craft as if it was an eggshell. He leant over the side and Clio saw his dirty hands and his thick, brown forearms. He seized Grace and with one movement lifted her up and over the side of his boat, her legs twisting and bumping. The fisherman laid her gently in the bottom of his boat. The sight of the inanimate body was shocking and pitiful. Clio knew that Grace was dead. She forced her hand against her mouth, suppressing a cry.

With the same ease, the fisherman hauled Hugo and Jake in after Grace. They sank down, staring, huddled together and trembling. Their hair was plastered over their faces, fair and dark, and seawater and spittle trailed out of their blue mouths.

The man leant across and lifted the trailing bow-rope of the Mabel. He made it fast to the stern of his own boat and then lifted his oars again. The two boats rose on the crest of a wave and plunged towards the beach.

A little knot of people had gathered, watching and waiting. As soon as the red boat came within wading distance, two men splashed out and hoisted the bundle of Grace between them. They ran back and grimly spread her on the sand, rolling her on to her belly, lifting her arms above her head.

Clio let herself be lifted in her turn, and then she was set gently on her feet. She wanted to run away up the beach, away from the sea that gnawed at her heels, but there was no power in her legs. She almost fell, but someone’s hands caught at her. Part of the murmuring crowd closed around her, and then she heard the very sound of the warm world, the lovely safe world. It was the faint crackle of starch. She lifted her head and saw Nanny’s apron, and half fell against it. The scent of laundry rooms and flatirons and safety overwhelmed her, and she looked up and saw Nanny Cooper’s face. Her cheeks were wet and her eyes were bulging with fear.

The boys had been hurried ashore. Jake and Hugo were shrouded in rugs and all of them became part of a circle that had Grace at its centre. The desperate business of the men with their huge hands, who bent over her and pounded at her narrow chest, seemed in futile contrast with her stillness.

Nanny Brodribb stood beyond them, her hands pressed against her face, her mouth moving soundlessly.

They waited a long time, only a few seconds.

Then Grace’s mouth opened. A flood of watery vomit gushed out of her. She choked, and drew in a sip of air. They saw her ribs shudder under the soaked dress.

The crowd gave a collective sigh, like a blessing. They closed in on what had become Grace again, living and breathing. Julius stumbled forward and tried to kneel beside her.

‘Give her room, can’t you?’ one of the men said roughly.

They turned Grace so that she lay on her back, and her eyes opened to stare at the sky.

Clio became aware of more movement beyond the intent circle. Blanche was coming, with Eleanor and Hills the chauffeur just behind her. The strangeness of it made her lift her eyes from Grace’s heaving ribs. There was no elegant glide now. Blanche’s head was jerking, she was hatless and her ribbons and laces flew around her. Clio had never seen her mother and her aunt running. It made them seem different people, strangers.

The two women reached the edge of the crowd and it opened to admit them to where Grace lay. Blanche dropped on her knees, giving a low moan, but no one spoke. They were listening to the faint gasps of Grace’s breathing, all of them, willing the next to follow the last. Jake and Hugo stood shivering under their wrappings of blankets. Nanny Cooper moved to try to warm them, with Clio still clinging to her apron. The other nanny began to trudge up the slope of the beach to where the small children had been left under the nursemaid’s eye. Clio took her eyes off Grace once more, to watch her bowed back receding.

They were all helpless, most noticeably the mothers themselves, kneeling with the wet sand and salt water soiling their morning dresses. They looked to the fishermen for what had to be done.

Grace’s stare became less fixed. Her eyes slowly moved, to her mother’s face. She was breathing steadily now, with no throat-clenching pauses between the draughts of air. The fisherman lifted her shoulders off the sand, supporting her in his arms. Another of the men came forward with a pewter flask. He put it to her mouth and tilted a dribble of brandy between her teeth. Grace shuddered and coughed as the spirit went down.

‘She’ll do,’ one of the men said.

Another blanket materialized. Grace was lifted and wrapped in the folds of it. Blanche came out of her frozen shock. She began to cry loudly, trying to pull Grace up and into her own arms, with Eleanor holding her back.

‘All right, my lady,’ another fisherman reassured her. ‘I’ve seen enough drownings. This isn’t one, I can promise you. Your boys got to her quick enough. Not that they should have took her out there in the beginning.’

In her cocoon of blanket, Grace shook her head. Her face was as waxen as if she had really died, but she opened her mouth and spoke clearly. ‘It was my fault, you know. Not anyone else’s.’

The fisherman laughed. ‘You’re a proper little bull-beef, aren’t you? Here. Let’s get you inside in the warm. Your ma’ll want to get the doctor in to look at you, although I’d say you don’t need him any more’n I do.’

He lifted Grace up in his arms and carried her. Blanche followed, supported by Eleanor and Hills on either side, and the children trailed after them, back to the big house overlooking the sea.

As soon as she was installed in her bed, propped up on pillows after the doctor’s visit, Grace seemed too strong ever to have brushed up against her own death. For a little while afterwards the boys even nicknamed her Bull-beef.

Clio remembered it all her life not as the day Grace nearly drowned, but as the day when she became aware herself that all their lives were fragile, and temporary, and precious, rather than eternal and immutable as she had always assumed them to be. She recalled how the land had looked when they were drifting away from it in the Mabel, and now that inviting warmth seemed to touch everything she looked at. The most mundane nursery routines seemed sweet, and valuable, as if they might stop tomorrow, for ever.

There must have been some maternal edict issued that morning for everything to continue as normal, more normally than normal, to lessen the shock for all of them. So the nannies whisked the older boys into dry jerseys and knickerbockers, and made Clio change her damp and sandy clothes, and by the time they had been brushed and tidied and inspected, and had drunk hot milk in the kitchen, the doctor had been and gone without any of them seeing him, and it was time for children’s lunch. There was fish and jam roly-poly, like any ordinary day. No one ate very much, except for Hugo who chewed stolidly. Clio wanted to cry out, Stay like this. Don’t let anything change. She wanted to put her arms around them all and hold them. But she kept silent, and pushed the heaps of roly-poly into the pools of custard on her plate.

Later in the afternoon, Clio found the two nannies together in the cubbyhole where the linen was folded. There was the same scent of starch and cleanliness that had drawn her back on the beach into the safe hold of childhood, but now she saw that both of the women had been crying. She knew they were afraid they would be dismissed for letting Grace go out in the boat.

‘It isn’t fair,’ Clio said hotly. ‘You couldn’t have stopped her. I couldn’t, nobody could. Grace always does what she wants.’ Anger bubbled up in her. Nanny Cooper had been with the Hirshes since Jake was born. She came from a house in one of the little brick terraces of west Oxford. The children had often been taken to visit her ancient parents. It was unthinkable that Grace should be responsible for her being sent away.

‘Don’t you worry,’ Nanny tried to console her. But it was one of the signs of the new day that Clio didn’t believe what she said.

In the evening Nathaniel arrived off the London train, summoned back early by Eleanor.

He called the three boys singly into a stuffy little room off the hallway that nobody had yet found a use for. They came out one by one, with stiff faces, and went up to their beds. When it came to Clio’s turn to be summoned she slipped into the room and found her father sitting in an armchair with his head resting on one hand. His expression and posture was so familiar from bedtimes at home in Oxford that her awareness of the small world’s benevolent order and fears for its loss swept over her again.

Nathaniel saw her face. ‘What is it, Clio?’

She had not meant to cry, but she couldn’t help herself. ‘I don’t want to grow up,’ she said stupidly.

He held out his hand, and made her settle on his lap as she had done when she was very small. ‘You have to,’ he told her. ‘Today was the beginning of it, wasn’t it?’

‘I suppose it was,’ Clio said at length.

But she found that her father could still reassure her, as he always had. He told her that there was no question of any blame being placed on Nanny Cooper for what Grace had done. And he told her that the changes, whatever they were, would only come by slow degrees. It was just that from today she would be ready for them.

‘What about Grace?’ Clio asked. ‘Is today the first day for her, as well?’

‘I don’t know so much about Grace,’ Nathaniel said gently. ‘I hope it is.’

Clio wanted to say some more, to make sure that Nathaniel knew Grace had insisted on going out in the Mabel, and that she had just been showing off when she leapt on to the seat. She supposed it was the same beginning to grow up that made her decide it would be better to keep quiet. She kissed her father instead, rubbing her cheek against the springy black mass of his beard.

‘Goodnight,’ she said quietly. As she went upstairs to the bedroom she shared with Grace she heard Nathaniel cross the hallway to the drawing room where the sisters were sitting together, and then the door closing on the low murmur of adult conversation.

Grace was still lying propped up on her pillows. Her dark hair had been brushed and it spread out in waves around her small face. A fire had been lit in the little iron grate, and the flickering light on the ceiling brought back memories of the night nursery and baby illnesses. Clio found herself instinctively sniffing for the scent of camphorated oil.

‘What’s happening down there?’ Grace asked cheerfully.

Clio didn’t return her smile. ‘Jake and Julius and Hugo have been put on the carpet for letting you out in the boat.’

‘It can’t have been too serious,’ Grace answered. ‘Jake and Julius have just been in to say goodnight. I thanked them very prettily for saving my life. They seemed quite happy.’

‘Aren’t you at all sorry for all the trouble you caused?’

Grace regarded her. ‘There isn’t anything to be gained from sorrow. It was an accident. I’m glad I’m not dead, that’s all.’ She stretched her arms lazily in her white nightgown. ‘I’m not ready to die. Nothing’s even begun yet.’

Clio didn’t try to say any more. She undressed in silence, and when she lay down she turned away from Grace and folded the sheet over her own head.

In the night, Grace dreamt that she was in the water again. The black weight of it poured over her, filling her lungs and choking the life out of her. When she opened her eyes she could see tiny faces hanging in the light, a long way over her head, and she knew that she was already dead and lying in the ground. She woke up, soaked in her own sweat and with a scream of terror rising in her throat. But she didn’t give voice to the scream. She wouldn’t wake Clio, or Nanny who was asleep in the room next door. Instead she held her pillow in her arms and bit down into it to maintain her silence. She kicked off the covers that constricted her, too much like the horrible weight of water, and lay until she shivered with the cold air drying the sweat on her skin.

At last, with her jaw aching from being clenched so tight, she knew that the nightmare had receded and she could trust herself not to cry out. Stiffly she drew the blankets over her shoulders and settled herself for sleep once again.

Downstairs, after Clio and the boys had gone up to bed, Nathaniel went into the drawing room where his wife and sister-in-law were sitting together. They had changed for dinner, and in their gowns with lace fichus and jewels and elaborate coiffures there was no outward sign of the day’s disturbances. He had not expected that there would be. Blanche and Eleanor were alike in their belief that civilized behaviour was the first essential of life. Nathaniel had been fascinated from the first meeting with her to discover how unconventional Eleanor could be, and yet still obey the rigid rules of her class. She had married him, after all, a Jew and a foreigner, and still remained as impeccably of the English upper classes as her sister the Countess. He smiled at the sight of the two of them.

Nathaniel kissed his wife fondly, and murmured to Blanche that she looked as beautiful as he had ever seen her, a credit to her own remarkable powers of composure after such a severe shock. Then he strolled away to the mahogany chiffonier and poured himself a large whisky and soda from the tray.

‘I still think we should try to reach John,’ Blanche announced.

Nathaniel sighed. They had already agreed that John would have been out with the guns all day, and that now he would have returned there was no real necessity to disturb him. ‘What could he do?’ he repeated, reasonably. ‘Leave the man to his pheasants and cards. Grace is all right. I have dealt with the boys.’

Blanche closed her eyes for a moment, shuddered a little. ‘It was all so very frightening.’ Her sister rested a hand on her arm in sympathy, looking appealingly up at her husband. Nathaniel took a stiff pull at his drink. He didn’t like having to act the disciplinarian, as he had done this evening to the three boys, particularly when he saw clearly enough that it was Grace who had been at fault. The business had made him hungry, and he was looking forward to his dinner. He was congratulating himself on not having to sit down to it with fussy, whiskery, humourless John Leominster for company. He did not want him summoned now, or at any time before he had conveyed himself back to Town or to Oxford.

‘It’s all over now,’ he soothed her. ‘Try to see it as a useful experience for them. Learning that rules are not made just to curb their pleasure.’

And I sound just as pompous about it as Leominster himself, Nathaniel thought. He laughed his deep, pleasing, bass laugh and drank the rest of his whisky at a gulp.

‘I’m sure you’re right,’ Eleanor supported him, and at last Blanche inclined her elegant head. The little parlourmaid who performed the butler’s duties in the holiday house came in to announce to her ladyship that dinner was served. Nathaniel cheerfully extended an arm to each sister and they swept across the sand-scented hallway to the dining room.

Nathaniel orchestrated the conversation ably, assisted by Eleanor, and they negotiated the entire meal without a single mention of death by drowning. At the end of it, when the ladies withdrew, Blanche was visibly happy again. There was no further mention of calling John back from his sport.

Nathaniel sat over his wine for a little longer. He was thinking about the children, mostly about Grace. He had not tried to lecture her, as he had done the boys. He had sat on the edge of her bed instead. Grace had faced him with the expression that was such a subtle mingling of Blanche and Eleanor and his own dreamy, clever, ambiguous Clio, and yet made a sum total that was quite different from all of them. He thought he read, behind her defiant eyes, that Grace had already been frightened enough and needed no further punishment.

They had talked instead about the girls learning to swim. He had made her laugh with imitations of the mothers’ reaction to the idea.

Now that he was alone Nathaniel let himself imagine the threat of Grace’s death, the possibility that he had denied to the women. His fist clenched around the stem of his glass as the unwelcome images presented themselves. It came to him then that he loved his niece. There was determination in her, and there was something else, too. It was an awareness of her own female power, and a readiness to use it. She was magnetic. It was no wonder that his own boys were enslaved by her, Nathaniel thought. And then he put down his glass and laughed at himself.

Grace was ten years old. There would come a time to worry about Grace and Jake, but it was not yet.

Nathaniel strolled outside to listen to the sea. He sat and smoked a cigar, watching the glimmering whitish line of the breakers in the dark. Then he threw the stub aside and went up to his wife’s bedroom.

Eleanor was sitting at her dressing table in her nightdress. Her long hair hung down and she was twisting it into a rope ready for bed. Nathaniel went to her and put his hands on her shoulders. He loved the straight line of her back, and the set of her head on her long neck.

Very slowly he bent his head and put his mouth against the warm, scented skin beneath her earlobe. Watching their reflections in the glass he thought of Beauty and the Beast. His coarse black beard moved against her white skin and shining hair as he lifted his hands around her throat and began to undo the pearly buttons.

‘Nathaniel,’ Eleanor murmured. ‘Tonight, of all nights, after what has happened?’

‘And what has happened? A childish escapade, with fortunately no damage done. All’s well, my love.’ He reassured her, as he had reassured Clio.

All’s well.

His hands moved inside her gown, spreading to lift the heavy weight of her breasts. He loved the amplitude of her, released from the day’s armour of whalebone and starch. She had a round, smooth belly, folds of dissolving flesh, fold on intricate fold. Eleanor gave a long sigh. She lifted her arms to place them around her husband’s neck. Her eyes had already gone hazy.

Eleanor had had four children. Even from the beginning, when she was a girl of twenty who barely knew what men were supposed to do, she had enjoyed her husband’s love-making. But it had never been so good as it was now, now when they were nearly middle-aged. Sometimes, in the day-time, when she looked up from her letters or lowered her parasol, he could meet her eye and make her blush.

He lifted her to her feet now so that she stood facing him. Nathaniel knelt down and took off her feathered satin slippers. Then he lifted up the hem of her nightgown to expose her blue-white legs. His beard tickled her skin as he laid his face against her thigh.

An hour later, Eleanor and Nathaniel fell asleep in each other’s arms. In all the dark house, Grace was the only one who lay awake. She held on to her pillow, and waited for the water and her fears to recede.

Two (#u2bf208d7-2a0d-5ee2-b00e-16756161e98b)

‘My mother was a Holborough, you know,’ Clio said.

Elizabeth did know. She also knew that Clio’s grandmother had been Miss Constance Earley, who had married Sir Hubert Holborough, Bt, of Holborough Hall, Leicestershire, in 1875. Her daughters had been born in April 1877.

Lady Holborough never fully recovered from the stress of the twin pregnancy and birth, and she lived the rest of her life as a semi-invalid. There were no more children. Blanche and Eleanor Holborough spent their childhood in rural isolation in Leicestershire, best friends as well as sisters.

Elizabeth knew all this, and more. She had the family diaries, letters, Bibles, copies of birth and death certificates, the biographer’s weight of bare facts and forgotten feelings from which to flesh out her people. She thought she knew more about the history of their antecedents than Clio had ever done, and Clio had forgotten so much. Clio could not even remember what they had talked about last time they met.

And yet Clio possessed rare pools of memory in which the water was so clear that she could stare down and see every detail of a single day, a day that had been submerged long ago by the flood of successive days pouring down upon it. Elizabeth wanted to lean over her shoulder and look into those pools too. That was why she came to sit in this room, with her miniature tape-recorder and her notebook, to look at reflections in still water.

‘A Holborough. Yes,’ Elizabeth said.

‘Mother used to tell me stories about when she was a little girl.’

When Blanche and Eleanor were girls, a hundred years ago.

‘What sort of stories?’

Clio gave her cunning look, to show that she was aware of the eagerness behind the question. ‘Stories …’ she said softly, on an expiring breath.

There was a silence, and then she began.

‘Holborough was a fine house. Not on the scale of Stretton, of course, but it was the first house in the neighbourhood. There was a maze in the gardens. Mother and Aunt Blanche used to lead new governesses into it and lose them. They knew every leaf and twig themselves. They would slip away and leave the poor creatures to wander all the afternoon. Then the gardeners would hear the pitiful cries, and come to the rescue.’

Elizabeth had visited Holborough Hall. After it had been sold in the Twenties it had been a preparatory school and then in wartime a training camp for Army Intelligence officers. After the war it had stood empty, and then seen service as a school again. Lately it had become a conference centre. The famous maze had survived, just. It looked very small and dusty, marooned in a wide sea of tarmac on which delegates parked their cars.

‘Can’t you imagine them?’ Clio was saying. ‘Identical little girls in pinafores, whisking gleefully and silently down the green alleys?’

Elizabeth smiled. ‘Yes, I can imagine.’

‘They had to make their own amusements. There were no other children. It wasn’t like it was for me, living in the middle of Oxford, with brothers and cousins always there.’

But it had been a happy childhood, Clio knew that, because Eleanor and Blanche often spoke of it. There had been carriage drives and calls with their mother, when she was well enough. There had been outings in winter to follow the hunt, with their father’s groom. Sir Hubert was an expert horseman. There had even been visits to London, to shop and to visit Earley relatives. There had been nannies and governesses and the affairs of the estate and the village. But most importantly of all, there had been the private world that they had created between them.

It was a world governed only by their imaginations, a mutual creation that released them from the carpet-bedded gardens and the crowded mid-Victorian interiors of Holborough, and set them free. They made their own voyages, their own discoveries, even spoke their own language. The intimacy of it lasted them all their lives, even when the intricate games were long forgotten.

Their imaginary world of play was put aside, reluctantly, when the real world judged that it was time for them to be grown up. Blanche and Eleanor accepted the judgement obediently, because they had been brought up to do as they were told, but they kept within themselves a component that remained childlike, together.

Eleanor’s husband Nathaniel thought it was this buried streak of childishness that gave them their air of unconventionality buttoned within perfect propriety. He found it very alluring.

When the twins reached the age of seventeen, Sir Hubert and Lady Holborough decided that their daughters must do the Season. Constance had been presented at Court as a d?butante, and in the same year she had been introduced to and then become engaged to Hubert. There had been little Society or London life for her in the years afterwards, because of her own ill-health and her husband’s addiction to field sports, but they were both agreed that there was no reason to deny their daughters their chances of a good marriage.

Constance was apprehensive, and her nervousness took the form of vague illness. But still, a house was taken in Town, and more robust and cosmopolitan Earley aunts were enlisted to launch their nieces into Society.

The twins brought few material or social advantages with them to London in 1895. Their father was a baronet of no particular distinction, except on the hunting field. Their mother came from an old family and had been a beauty in her day, but she had not been much seen for more than fifteen years. There was no great fortune on either side.

But still, against the odds, perhaps because they didn’t care whether they were or not, the Misses Holborough were a success.

They were not beautiful. They had tall foreheads and narrow, too-long noses, but they had handsome figures and large dark eyes and expressive mouths that often seemed to register private amusement. Nathaniel Hirsh was not the first man to be attracted by their obviously enjoyable unity in an exclusive company of two. They began to be invited, and then to be courted. Young men joked about declaring their love to a Miss Holborough on one evening, and then discovering on the next that they had fervently reiterated it to the wrong one.

The joke was more often Blanche and Eleanor’s own. It amused them to tease. From infancy they had used their likeness to play tricks on nannies and governesses, and it seemed natural to extend the game to their dancing partners. They wore one another’s gowns and exchanged their feathered headdresses, became the other for a night and then switched back again. They acquired a reputation for liveliness that added to their appeal.

One evening towards the end of the Season there was a ball at Norfolk House. Blanche and Eleanor had received their cards, and because Lady Holborough was unwell they were chaperoned by Aunt Frederica Earley. Sir Hubert escorted them, although he had no patience with either dancing or polite conversation. He was anxious for the tedium of parading his daughters through the marriage market to be over and done with, so he could return home to Leicestershire and his horses. He had already announced to his wife that he considered the whole affair to be a waste of his time and his money, since neither girl showed any inclination to choose a husband, or to do anything except whisper and giggle with her sister.

The Duchess’s ballroom was crowded, and the twins were soon swept into the dancing. Their aunt, having married her own daughters, was free to watch them with proprietary approval. Blanche was in rose pink and Eleanor in silver. They looked elegant and they moved gracefully. They had no particular advantages, the poor lambs, but they would do. Mrs Earley was not worried about them.

She was not the only onlooker who followed the swirls of rose pink and silver through the dance.

There was an urbane-looking gentleman at the end of the room who watched the mirror faces as they swung, and smiled, and swung again. The room was full of reflections but these were brighter; their images doubled each other until the ballroom seemed full of dark hair and assertive noses and cool, interrogative glances.

The gentleman inclined his head to one of the ladies who sat beside him. ‘Who are they?’ he asked.

The woman fastened a button at the wrist of her long white glove.

‘They are the Misses Holborough,’ she answered. ‘Twins,’ she added unnecessarily, and with a touch of disapproval in her voice that made it sound as if it was careless of them.

‘They are interesting,’ the man said. ‘Do you know their family?’

‘The lady in blue, over there, is their aunt. Mrs Earley. I am acquainted with her. Their mother is an invalid, I believe, and their father is a bore. I would be happy to give you any more information, if I possessed it.’

The man laughed. His companion had daughters in the room who were not yet married and who were much less intriguing than the Misses Holborough. He asked, ‘And may I be presented to Mrs Earley?’

A moment later, he was bowing over another gloved hand.

‘Mr John Singer Sargent,’ Mrs Earley’s acquaintance announced.

‘I should very much like to paint your nieces, Mrs Earley,’ the artist said.

Mrs Earley was flattered, and agreed that it was a charming idea, but regretted that the suggestion would have to be put to Sir Hubert, her brother-in-law. When Sir Hubert re-appeared in the ballroom he was still smarting from the loss of fifty-six guineas at a friendly game of cards, and he was not in a good humour. Fortunately Mr Sargent had moved away, and was not in the vicinity to hear the response to his proposal.

Sir Hubert said that he couldn’t imagine what the fellow was thinking of, wanting him to pay some no doubt colossal sum for a pretty portrait of two silly girls who had never had a sensible thought in their lives. The answer was certainly not. It was a piece of vanity, and he wanted to hear no more about it.

‘You make yourself quite clear, Hubert,’ Mrs Earley said, pressing her lips together. No wonder Constance was always indisposed, she thought.

The ball was over. Blanche and Eleanor presented themselves with flushed cheeks and bright eyes and the pleasure of the latest tease reverberating between them. The Holboroughs’ carriage was called and the party made its way home, to Sir Hubert’s obvious satisfaction.

The end of the Season came. The lease on the town house ran out and the family went back to Holborough Hall. Blanche and Eleanor were the only ones who were not disappointed by the fact that there was no news of an engagement for either of them. They had had a wonderful time, and they were ready to repeat the experience next year. They had no doubt that they could choose a husband apiece when they were quite ready.

The autumn brought the start of the hunting season. For Sir Hubert it was the moment when the year was reborn. From the end of October to the beginning of March, from his estate outside the hunting town of Melton Mowbray, Sir Hubert could ride to hounds if he wished on six days of every week. There were five days with the Melton packs, the Quorn, the Cottesmore and the Belvoir, and a sixth to be had with the Fernie in South Leicestershire. There were ten hunters in the boxes in the yard at Holborough for Sir Hubert and his friends, and a bevy of grooms to tend them and to ride the second horses out to meet the hunt at the beginning of the afternoon’s sport.

The hall filled up with red-faced gentlemen whose conversation did not extend beyond horses and hunting. They rode out during the day, and in the evenings they ate and drank, played billiards, and gambled heavily.

Now that they were out, Blanche and Eleanor were expected to join the parties for dinner. They listened dutifully to the hunting talk, and kept their mother company after dinner in the drawing room, while the men sat over their port or adjourned to the card tables in the smoking room.

‘Is this what it will be like when we are married?’ Blanche whispered, trying to press a yawn back between her lips.

‘It depends upon whom we marry, doesn’t it?’ Eleanor said, with a touch of grimness that was new to her.

Then one night there was a new guest at dinner, a little younger and less red-faced than Sir Hubert’s usual companions. He was introduced to the Holborough ladies as the Earl of Leominster.

They learnt that Lord Leominster lived at Stretton, in Shropshire, and that he also owned a small hunting box near Melton. The house was usually let for the season, but this year the owner was occupying it himself with a small party of friends. Sir Hubert and his lordship had met when they enjoyed a particularly good day out with the Quorn and, both of them having failed to meet their grooms at dusk, they had hacked part of the way home together.

Lord Leominster had accepted his new friend’s invitation to dine.

On the first evening, Eleanor and Blanche regarded him without much favour. John Leominster was a thin, fair-skinned man in his early thirties. He had a dry, careful manner that made an odd contrast with the rest of Sir Hubert’s vociferous friends.

‘Quiet sort of fellow,’ Sir Hubert judged. ‘Can’t tell what he’s thinking. But he goes well. Keen as mustard over the fences, you should see him.’

Lady Holborough quickly established that his lordship was unmarried.

‘Just think, girls,’ she whispered. ‘What a chance for one of you. Stop smirking, Eleanor, do. It isn’t funny at all.’

The girls rolled their eyes at each other. Lord Leominster seemed very old and hopelessly shrivelled from their eighteen-year-old standpoint. They were much more interested in the cavalry officers from the army remount depot in Melton.

But it soon became clear that the twins had attracted his attention, as they drew everyone else’s that winter. Against the brown setting of Holborough they were as exotic and surprising as a pair of pink camellias on a February morning. After the first dinner he called again, and then became a regular visitor.

It was also evident, from the very beginning, that he could tell the two of them apart as easily as their mother could. There were no mischievous games of substitution. Eleanor was Eleanor, and Blanche was the favoured one.

John Leominster became the first event in their lives that they did not share, did not dissect between them.

Eleanor was startled and hurt, and she took refuge in mockery. She called him Sticks for his thin legs, and before she spoke she cleared her throat affectedly in the way that Leominster did before making one of his considered pronouncements. She made sure that Blanche saw his finicky ways with gloves and handkerchiefs, and waited for her sister to join her in the mild ridicule. But Blanche did not, and they became aware that a tiny distance was opening between them.

Blanche was torn. After the first evening she felt guilty in not responding to Eleanor’s overtures, but she began to feel flattered by the Earl of Leominster’s attention. She was also surprised to discover how pleasant it was to be singled out for herself alone, instead of always as one half of another whole. As the days and then the weeks passed, she was aware of everyone in the household watching and waiting to see what would happen, and of Constance almost holding her breath. She saw her suitor’s thin legs and fussy manners as clearly as her sister did, but then she thought, The Countess of Leominster …

One night Eleanor asked impulsively, ‘What are you going to do, Blanche? About Sticks, I mean?’

‘Don’t call him that. I can’t do anything. I have to wait for him to offer, don’t I?’

Eleanor stared at her. Until that moment she had not fully understood that her sister meant to accept him if he did propose marriage.

‘Oh, Blanchie. You can’t marry him. You don’t love him, do you?’

Blanche pulled out a long ringlet of hair and wound it round her forefinger. It was a characteristic mannerism, familiar to Eleanor from their earliest years. ‘I love you,’ Eleanor shouted. ‘I won’t let him take you away.’

‘Shh, Ellie.’ Blanche was deeply troubled. ‘We both have to marry somebody, someday, don’t we? If I don’t love him now, I can learn to. He’s a kind man. And there’s the title, and Stretton, and everything else. I can’t turn him down, can I?’

Eleanor shouted again. ‘Yes, you can. Neither of us will marry anyone. We’ll live together. Who needs a husband?’

Slowly, Blanche shook her head. ‘We do. Women do,’ she whispered.

Eleanor saw that her sister was crying. There were tears in her own eyes, and she stood up and put her arms round Blanche. ‘Go on, go on then. Make yourself a Countess. Just have me to stay in your house. Let me be aunt to all the little Strettons. Just try to stop me being there.’

Blanche answered, ‘I won’t. I never would.’

They cried a little, shedding tears for the end of their childhood. And then, with a not completely disagreeable sense of melancholy, they agreed that they had better sleep or else look like witches in the morning.

There came the evening of an informal dance held in the wooden hall of the village next to Holborough. The twins dressed in their rose pink and silver, and sighed that Beecham village hall was a long way from Norfolk House. But there was a large contingent of whooping army officers at Beecham, and there was also John Leominster. While Eleanor was passed from arm to arm in the energetic dancing, Blanche agreed that she would take a respite from the heat and noise, and stroll outside the hall with her partner.

Lady Holborough inclined her head to give permission as they passed the row of chaperones, and Blanche knew that all their eyes were on them as they passed out into the night. It was a mild evening, but she drew her fur wrap tightly around her shoulders like a protective skin. She was ready, but she was also afraid. They walked, treading carefully over the rough ground.

‘Blanche, you know that I would very much like you to see Stretton, and to introduce you to my mother.’

Blanche inclined her head, but she said nothing.

John cleared his throat. She was irresistibly reminded of Eleanor’s mimicry, but she made herself put Eleanor out of her mind, and concentrate on what was coming. It was, she knew, the most important moment of her life. If it seemed disappointing that it should have come now, outside the barn-like hall at the end of a rutted country lane, then she put her disappointment aside and waited.

‘I think you know what I want to say to you. Blanche, my dear, will you marry me?’

There was nothing more to wait for. There it was, spoken.

‘Yes, John. I will,’ Blanche said. Her voice sounded very small.

He stopped walking and took her in his arms. His lips, when they touched hers, were soft and dry and they did not move. That seemed to be all there was.

‘I shall speak to your father in the morning,’ John said. He took her hand and they turned to walk back towards the hall. ‘You make me very happy,’ he said.

‘I’m glad,’ Blanche answered.

After the engagement was announced, his lordship seemed to become aware of the bond between his fianc?e and her twin sister. It was as if he could safely acknowledge its existence, now that he had made sure of Blanche for himself. He reminisced about how he had first seen them, coming arm in arm into the drawing room at Holborough.

‘As lovely as a pair of swans on a lake,’ he said, surprising them with a rare verbal flourish. Blanche smiled at him, and he put his hand on her arm. He took the opportunity to tell the sisters he wished to have their portrait painted. The double portrait would mark his engagement to Blanche, but it would also celebrate the Misses Holborough. He had already chosen the artist. It was to be Sargent.

When the spring came, Lady Holborough and her daughters removed to London. Blanche’s wedding clothes and trousseau needed to be bought, and there were preparations to be made for Eleanor’s second Season. They settled at Aunt Frederica Earley’s house, and in the intervals between shopping and dressmakers’ appointments the twins presented themselves for sittings at Mr Sargent’s studio.

They enjoyed their afternoons with the painter. He had droll American manners, he made them laugh, and he listened with amusement to their talk.

The portrait, as it emerged, reflected their rapport.

The girls were posed on a green velvet-padded love seat. Blanche faced forwards, dressed in creamy silk with ruffles of lace at her throat and elbows. Her head was tilted to one side, as if she was listening to her sister’s talk, although her dark eyes looked straight out of the canvas. Her forefinger marked her place in the book on her lap. Eleanor faced in the opposite direction, but the painter had turned her so that she looked back over her own shoulder, her eyes following the same direction as her sister’s. Their mouths were painted as if they were on the point of curving into smiles, the eyes were bright with laughter and the dark eyebrows arched questioningly over them. Eleanor wore sky-blue satin, with a navy-blue velvet ribbon around her throat.

Their white, rounded forearms rested side by side on the serpentine back of the love seat. It was a pretty pose.

The girls looked what they were, identically young and innocent and good-humoured. There was no need for Mr Sargent to soften any of the sharpness of his vision with superficial flattery. He painted what had first attracted him in the ballroom at Norfolk House, twin images of lively inexperience.

‘You have made us look too pretty,’ Eleanor told him.

‘I have painted you as I see you,’ he answered. ‘I can do no more, and I would not wish to do less.’

‘We look happy,’ Blanche observed.

‘And so you should,’ John Sargent told her, with the advantage of more than twenty years’ longer experience of the world. ‘You should be happy.’

Even then, the girls understood that he had captured their girlhood for them on canvas, just at the point when it was ending.

The Misses Holborough was judged a success. John Leominster paid for the double portrait, and after the wedding it was transported to Stretton where it was hung in the saloon. Blanche sometimes hesitated in front of it, sighing as she passed by.

Eleanor was often at Stretton with her, but she could not always be there. Blanche missed her, but she was also occupied with trying to please her husband, and with the peculiar responsibilities of taking over from her mother-in-law as the mistress of the old house. The separation was much harder for Eleanor.