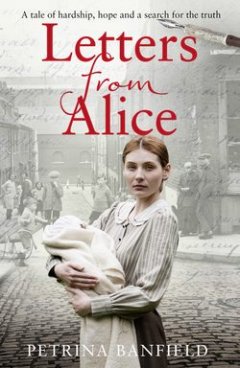

Letters from Alice: A tale of hardship and hope. A search for the truth.

Àâòîð:Petrina Banfield

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:923.11 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 272

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 923.11 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Letters from Alice: A tale of hardship and hope. A search for the truth.

Petrina Banfield

Two women. One secret. Will they be able to keep it under wraps?It was a stormy evening in 1920s London. When newly qualified almoner, Alice, stepped into the home of Charlotte, a terrified teenager who had just given birth out of wedlock, she did not expect to make a pact that would change her life forever. Thrown into secrecy after an unexpected turn, Alice was determined to keep bewildered Charlotte and her newborn baby safe. But when a threatening note appeared, she realised that Charlotte may need more protection than she first thought. But from who?Based on extensive research into the archive material held at the London Metropolitan Archives, and enriched with lively social history and excerpts from newspaper articles, LETTERS FROM ALICE is a gripping and deeply moving tale, which brings the colourful world of 1920s London to life. Full of grit, mystery and hope, it will have readers enthralled from the very first page.

(#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

Copyright (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This edition published by HarperElement 2018

FIRST EDITION

© Petrina Banfield 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover image © Jeff Cottenden (posed by model); Hawkins/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images (street scene); Shutterstock.com (all other images)

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Petrina Banfield asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008264703

Ebook Edition © August 2018 ISBN: 9780008264710

Version: 2018-06-21

Dedication (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

Happy memories

SYLVIA ELLEN LOCKYER

Contents

Cover (#u447c37e0-e0d8-542e-b5f0-3d9914ac6416)

Title Page (#ud59d7320-f72e-5c09-aa16-331ec874e8dd)

Copyright (#u3b33f18b-8ec0-5ca3-9e7f-7e711cd887e2)

Dedication (#ub1a35e8f-4ce0-5afb-acf5-f105301919e5)

Note to Reader (#u8f8a26f9-72bf-5b5f-aac8-9be146dd6275)

Prologue (#u6afb95a3-1e7f-5880-8d33-d8a5f1a65959)

Chapter One (#u48e80208-7c0c-557e-9432-488db193ef7e)

Chapter Two (#u0e9e2339-23c2-5cdb-9296-c0208f73afbe)

Chapter Three (#u4d635628-12b5-5b6d-af42-e18e8ca628dc)

Chapter Four (#u04ecb7de-51fa-5e7b-bed2-c682ca2c579a)

Chapter Five (#uf5e3c3e1-3789-5635-95c8-263fb9e0edc3)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

References (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Note to Reader (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

I was thirteen years old when I first discovered that my father spent his childhood in care. Until then he had never spoken to me about his past and, as children are so adept at doing, I somehow picked up that it was a subject to be tiptoed around, without ever having been told. The truth came out one Sunday afternoon after I plucked up the courage to ask for the names of my paternal grandparents, so that I could complete a genealogy project for school.

Perhaps he felt I’d reached an age of understanding because after a moment’s hesitation he told me that he knew very little about his parents, who had died long before I was born. Even this snippet of information was fascinating to me and I listened eagerly as he told me about the grandmother I’d never met – a petite Irish woman who had experienced too much pain and not enough love. By the age of twenty-five she had given birth to five children.

The shadow cast by childhood trauma stretched far into the future though, and in 1941 three of her children were taken into care, including my father and his twin brother – the youngest, at six months old.

Ever since hearing my father’s story I’ve been captivated by the idea of the corporate parent; society waiting with a safety net to cradle those most in need. For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to be part of that narrative. I finally applied to become a foster carer in 2006.

On my initial ‘Skills to Foster’ training course, the tutor told us that three fates awaited unwanted children of the distant past: death by exposure, prostitution or Christian adoption. We learned that homeless children and orphans in Britain were first ‘boarded out’ with foster carers in the latter part of the nineteenth century and that hospital almoners were the forerunners of modern social workers. But it was only in 2014, in trying to reassemble the scattered fragments of my father’s childhood puzzle, that I learned more about the almoners’ remarkable work.

I knew that Dad suffered with severe eczema as a child (he was separated from his twin at the age of five, his weeping wounds perhaps a physical manifestation of his sense of loss) and spent prolonged periods of time in hospital in London at some time during the Second World War, so I visited the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) and began my search there.

Not really knowing where to start, I put in a request for old files from the Royal Free Hospital and its associated hostels in London. Within half an hour, several boxes had arrived in the reading room. Excitedly, I started going through the first one and, beneath the envelopes filled with receipts and manila files tied up with string, I found a smaller box containing almoners’ reports from the 1920s.

As I worked my way through the dusty papers I read about girls ‘very young, not more than sixteen or seventeen years old’, who had ‘fallen into trouble’ as a result of living in conditions that were ‘past belief … involving very grave and unusual risks of infection’. As well as being pregnant, homeless and ‘turned adrift’ by their families, some of the poor girls were in agony as a result of a double infection of syphilis and gonorrhoea.

One almoner recorded that one of her patients, a girl suffering from gonorrhoea, was ‘one of six siblings who all slept in one bed, in a room like a cupboard, with no outer air’. Another young girl ‘lived over a stable with no access except by a ladder-like stair’.

On arrival at hospital many were ‘in a state of nervous and physical exhaustion, and of resentment requiring great tact and care in dealing with them. Some [were] put to bed, till the irritable condition of their nerves [was] soothed, and many of them [slept] for days … some descend[ing] to the depths of despair [,] bringing them to the verge of insanity’.

As I leafed through the file of fragile papers, a small bundle of handwritten letters written by one of the almoners – here, I will refer to her as Alice – fell out from between the pages. Beautifully written in a gently sloping script of fading black ink, and without a trace of the toxic condemnation that awaited the girls in society at large, they showed the almoner reaching out to her contacts in the community in search of ‘well-disposed people’ who might find it in their hearts to take them in.

A picture of Alice began to emerge: a fiercely intelligent woman from a sheltered background, filled with a sense of purpose and unafraid to challenge the conventions of the day. In Letters From Alice, Alice’s character, her attitudes and motivations are drawn from the common experiences of women of her time and social station; she belongs to a generation of women emboldened by the progress of the Suffragette movement and ready to make their voices heard. Striding around some of the poorest parts of London in her ankle-length skirts, I imagined Alice immersed in a world of complex social problems, ones that resonate strongly with me as a foster carer today: homelessness and deprivation, incarceration, domestic violence, intoxication from opium and alcohol, and, inevitably, the neglect and deliberate abuse of children.

What follows is a retelling of the experiences of one of the girls (I will call her Charlotte) through the eyes of Alice, using the letters, almoners’ reports and case files from the LMA as inspiration. Quotes have been lifted directly from the archive material, unless otherwise stated. Weather reports have been sourced from the Meteorological Office. Where the records are scant or incomplete, I have drawn on my research of the morals and expectations of society through the 1920s and my own imagination, to inject character into the disembodied voices in the reports and bring the stories to life on the page.

Prologue (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

Unlike doctors and nurses [the almoner] is a newcomer in the hospital world, but she finds all the benefits of its traditions at her disposal. Whether the almoner is there or not, a tapestry is being woven by the work of the hospital, but it may be an incomplete piece of work and apt to unravel if she does not play her part in gathering up and connecting the broken threads.

(The Hospital Almoner: A Brief Study of Hospital Social Science in Great Britain, 1910)

It was a little before seven o’clock in the evening on 17 April 1921 when twenty-eight-year-old almoner Alice Hudson summoned the police constable for help.

PC Hardwicke’s heavy boots tramped over the icy pavements in the east London district of Bow, Alice leading the way a few steps ahead. The weather during early April had been milder than usual, but over the last few days the temperature had plummeted, a depression from Iceland bringing gales over the eastern coasts and snow showers to the capital.

Daylight was beginning to fade as they reached their destination: a two-storey boarding house flanked by a derelict pub and a paper merchants. Alice had stopped by to see Molly Rainham half an hour earlier through concern for the young mother’s welfare, she later reported to the coroner. Despite knocking for several minutes and tapping on the frosted window pane, the only response had been an unidentifiable, plaintive bleat in the distance.

Hospital almoners were accustomed to a variety of reactions to their unannounced visits, but there was something strange about the silence echoing around the hall on the other side of Molly’s front door; a ghostly stillness that had sent Alice hurrying to the local police station.

From the notes in the almoner’s file back at the Royal Free Hospital, Alice knew that Molly may have been suffering from post-natal psychosis. According to reports she had initially coped well with motherhood, but seemingly overnight her demeanour had changed. With her husband on a military posting in Constantinople and no other family to speak of, Alice made a point of calling in on her patient whenever her schedule allowed.

‘We need to break in,’ the almoner insisted, as PC Hardwicke rapped again on the front door.

He was still tapping half a minute later as Alice scrabbled at the downstairs window and wrenched it upwards. Before the PC managed to reach the almoner, his long-tailed dark blue coat flapping behind him, she had already bunched the damp hem of her long skirt up in one hand and was clutching at the window frame with the other. In one motion she crawled forwards and hauled herself over the sill, the bobby pivoting on his heels and averting his eyes behind her.

A hundred yards to the east, the bells of St Mary le Bow boomed the hour. As the policeman followed Alice through the window, a seagull cried out mournfully in the darkening sky above, a reminder to the onlookers that had begun to gather outside the small property of their proximity to the docks and the wide sea beyond.

The passageway was dark. Perhaps to soften the impact of a sudden intrusion, Alice and the PC slowed when they reached the top of the stairs, then exchanged glances. Besides an unpleasant smell, there was an undertone of something else in the air, something disturbing. With a grim expression, the bobby turned towards the master bedroom at the front of the house.

A few steps later he faltered, stopping so abruptly that Alice almost walked into the back of him. The groan that escaped him should have offered some warning of the scene awaiting her, but when Alice stepped forwards she gasped in horror. Inside the room on a bloodstained mattress, Molly was stretched out on her back, her eyes and mouth gaping. The sinews in her neck were taut, her powdered cheeks etched with the chalky deposits of dried-up tears.

It was Alice who reached the bed first. The emergency drills she had learned as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse assessing casualties during the war years came back to her instantly. She ran her eyes over Molly, methodically checking for vital signs. Half a second later, she turned to the constable, gave a grim shake of her head then hurried past him into the hall.

The door to the small bedroom at the back of the house stood open. Alice hesitated in the doorway for a brief moment, then ran over to the cot by the window, where Molly’s infant son lay. Bracing herself, she leaned over to feel the skin at the back of his neck. Her legs buckled then – it was warm to the touch. Had she been half an hour earlier in rousing the alarm, the deputy coroner for east London later reported to the inquest held in Stepney, the baby boy might have been saved.

The death of Molly and her son was the first in a series of shocking cases that Alice Hudson became involved in, one that marked a turning point in her career, redefining the way she viewed herself and the world around her. When Alice returned to the Royal Free Hospital on Gray’s Inn Road and wrote up her report of the incident, she was unaware of the tangled threads that tied Molly to a case that rocked her above all others: the web of deception that began to unravel months later, on New Year’s Eve, 1921.

Chapter One (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

The question of the abuse of voluntary hospitals is one of wide knowledge. It has led to the creation of the hospital almoner, and there is a great future in front of her … Students should be between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-five, and the more knowledge of the world and of general interests that they can bring to their training, which lasts at least eighteen months, the better.

(Pall Mall Gazette, 1915)

By the middle of the afternoon on 31 December 1921, Alice Hudson had ticked off almost all of the duties on her weekend list.

It was three degrees Celsius, the sort of weather that prescribed hot drinks and thick blankets, and the almoner might have spent the day huddled in front of the log fire in the nurses’ home instead of trudging across the icy streets of east London, had it not been for the pile of urgent home visits weighing down the desk of her basement office.

Although December 1921 had been generally mild, Londoners shouldered frequent high winds and gales towards the end of the month. Today, Saturday, there was a cloud of sulphur in the air, the sky stretching over the Thames as grey as the sediment lurking at its depths. Conditions were likely to worsen over the next few hours but, all being well, Alice would be back in her room before dark.

The signs were promising. It was 2.30 p.m. and she was already three calls down, with only one to go.

The almoner took hurried, lopsided steps along the pavement overlooking the river, a briefcase full of patient files bumping against her ankle-length cape. In the distance, the faint blue glow from the lamplighter’s pole twinkled reflectively over the surface of the Thames as he worked his way, much earlier than usual, along Tower Bridge. Several children had walked unwittingly through the vapours into the frozen waters during the last terrible smog. The flickering lights glinting over the water offered at least some degree of reassurance for pedestrians.

Fifty-seven years old and possessed of an unruly beard, portly physique and a loud but undeniable charm, Frank Worthington strode ahead, smoking his ever-present pipe. A newly appointed board member of the Charity Organisation Society, or COS, Frank had shadowed Alice in the last fortnight, apparently to report back to the board on the benefits of the almoners’ work.

Besides arranging financial assistance and practical support for patients in times of crisis, or improving their living conditions so that they were able to benefit from their hospital treatment, Alice was expected to identify those families with the means to make a small contribution, thereby increasing the hospital’s income and justifying the cost of her own salary.

Peering beneath the veneer of the family and making judgements about their financial situation while at the same time maintaining a friendly, trusting relationship was a tricky balancing act for the almoners, however, one that could easily swing out of kilter.

Some families fiercely resented the intrusion of home visits, particularly those that were unannounced. Alice quickly learned to brace herself against the inevitable shock on the faces of her subjects, the rising unpredictability that could beset any unannounced visit, the ever-present possibility of violence.

Not that it always helped to be mentally prepared. On one surprise home visit, Alice was pelted from an upstairs window with some foul-smelling, ominously yellow soggy rags. Another time, she lost her thumbnail in a ferociously slammed door.

According to the almoner’s file on the last family they planned to visit, the Redbournes persistently claimed poverty, but were known to frequent several of the newly opened jazz clubs in the West End. While the question mark over their earnings was a matter that required further investigation, however, it wasn’t the almoner’s biggest concern.

The Redbourne family file was marked with an asterisk; a code to indicate to the team that theirs might be a case that warranted closer inspection.

When Alice’s boss, Bess Campbell, had first visited the family in their small house in Dock Street, she later documented that she had found the children home alone. Mrs Redbourne had staggered back arm-in-arm with one of her neighbours singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ at the top of her voice while the Lady Almoner conducted a conversation with one of her youngest through the letterbox.

There were five children in the family, three of whom had received treatment in the outpatients department for dysentery. It was a condition feared by parents across the city: the summer diarrhoea of 1911 claimed the lives of 32,000 babies under the age of one, the plethora of flies attracted by horse manure on the streets speeding up the transmission of disease. The Redbournes’ youngest, a boy of around a year old named Henry, had fallen sick with pneumonia soon after recovering from his bout of dysentery. According to the physician who treated him, he had been lucky to survive.

As a porter on the railways, Mr George Redbourne earned a reasonable wage, one that, according to Miss Campbell, should have been sufficient to allow the family to contribute sixpence a week towards the cost of their medical treatment. A typical wage for someone like Mr Redbourne in the early 1920s was around thirty to forty shillings a week (in old money, there were twelve pennies in a shilling, and twenty shillings to a pound).

The Redbournes insisted that the rest of their income, after the eight shillings and sixpence a week they paid out in rent, was swallowed up by tram fares to and from work, payments to elderly parents and other essentials. So far, not a penny of the costs of the family’s treatment had been recouped.

Trouble with nerves prevented Mrs Redbourne from working, or so she claimed, but she was a reluctant interviewee, and her word was not entirely trusted. The margin of the Redbournes’ file was marked with the letters ‘NF’: the almoners’ code for ‘Not Friendly’. It was a practice taught in training, one that forewarned visiting staff to be on their guard.

Across the river, a barge billowed steam into the air. Frank stopped abruptly as a horse cantered past, its cart loaded with coal. ‘Miss Hudson, you’ve made your point,’ he said, tilting his head towards the briefcase. ‘You’re as capable as any man, I accept it. I just wish you’d give up your desire to become one.’

Alice stopped, resting the briefcase on the ground and shaking her hands to get the blood flowing again. Tentatively, she loosened the silk scarf she was wearing, wincing as she tucked the end inside her cape. A collection of scarves in assorted colours hung in Alice’s wardrobe back in her room. She alternated them throughout the seasons to conceal the burn injury she sustained in the trench fire that had sent her home to England, the rough scars running across her left shoulder, up to the nape of her neck and over the back of her left hand.

‘Don’t worry, Frank,’ came the curt reply. ‘If ever I had such ambition, you are more than enough to contain it.’ Frank chuckled and set off again through the resulting cloud of smoke, unburdened but for the folded umbrella he tapped on the ground in front of him.

Alice picked up pace, the bells of Southwark Cathedral jangling in time with her steps. As they neared Whitechapel, walking the same streets stalked by Jack the Ripper a few decades earlier, they passed several tenements, silent but for the distant yowls of a stray dog. With shoeless children using stones for marbles on the icy pavements and coatless beggars huddling against crumbling walls, it was an area well known to the almoners.

Hurrying past the destitute with nothing to offer but a concerned smile must have been demoralising for a committed social reformer like Alice, but the almoners soon learned the difficult and humbling lesson that all social workers through the ages come to accept: you can’t help everyone.

Frank slowed as they neared a warren of three-storied houses with overhanging eaves. The smoke rising from chimneys all along Dock Street would likely worsen the weather conditions, but at least offered the promise of a room warmed by a log fire.

Alice reached Frank a few doors away from their destination. The trail of acrid smoke he left in his wake caught in her throat and she gave a sudden cough. Frank stopped mid-pace, draped the handle of his umbrella over the crook of one arm and held out his other hand to take possession of the briefcase. ‘May I?’ he asked, pipe dangling from between his teeth. With a slow roll of her eyes, Alice relinquished the suitcase. Frank immediately stood aside, gesturing for her to take the lead with a flourish of his brolly.

The Redbournes’ rickety wooden gate gave a resentful moan on opening, the yard empty but for a skinny cat curled up inside an old cardboard box. Lifting its head, the creature eyed them sorrowfully and then gave a mournful yowl. Alice crouched down, stroked its cold, velvety ears and whispered a soft hello.

The rug appeared out of the door without warning, just as Frank reached the front step. With a pitiful yelp he dropped both briefcase and brolly and staggered backwards to the gate, flapping his hands madly at his hair and face. Seemingly oblivious to her visitors, the woman brandishing the rug continued with the task, shaking it violently, eyes and mouth pinched tight against the spiralling dust.

It was only when Alice rose to her feet that Mrs Redbourne noticed them.

‘Oh,’ she said, staring at them agog. Frank, doubled over and gasping as he clutched at the fence post for support, looked for all the world as if he’d just left the battlefield. Alice’s mouth twitched as if stifling a giggle. A movement of the curtain at next door’s window, and the appearance of an elderly woman with curly grey hair on the other side of the glass, was a reminder of the need for discretion.

‘I am sorry to trouble you, Mrs Redbourne,’ Alice said softly. The cat raised itself and coiled her ankles in a figure of eight, disappearing beneath the hem of her skirt and reappearing at intervals. A passer-by stopped outside the house. Hat in hand, the elderly gentleman stared unabashedly at their small party. Alice lowered her voice still further. ‘We are from the Royal Free Hospital. Would you mind if we came in?’

Mrs Redbourne gave Alice a long look. The files back at the Royal Free stated that she was in her early forties, but her stern expression made her appear much older. Her hair had been combed into a grid-like pattern, each square grey tress curled, secured with pins and kept in place with a dark scarf. The rim of the scarf pulled tightly on the lined skin around her forehead, rendering her pink-rimmed eyes severe. She began to work her mouth as if chewing and then she said: ‘We’re in the middle of things just now.’

‘We shan’t take much of your time. We would like to check a few facts with you, and leave you with some information about our subscription scheme.’

The woman’s face contorted further. ‘That won’t be necessary. We have all the information we need, thank you very much.’ Steadfastly blocking their entrance with her wide girth, she folded the rug against the apron she wore like a shield, her lips stretched into a thin line.

Alice opened her mouth to speak. Before she managed to say a word, however, Frank, recomposed, grabbed his umbrella and nudged it against her skirt, half-pointing, half-thrusting it into the hall. ‘If you’d be so kind, Madam,’ he said, easing Alice aside with a fractional movement of his wrist. The expression on Mrs Redbourne’s face suggested that she wasn’t going anywhere, but a few moments later the woman flattened herself against the open door and let them through.

Alice met Frank’s satisfied look with another curt nod. She followed him into the hall, hovering at the open door for a fraction of a second before moving aside to allow Mrs Redbourne to close it behind them.

The almoner ran her eyes around the Redbournes’ hall. It was bright and clear of debris, the floor recently swept. There was a darkened rectangle where a rug must have been, the rest of the space dominated by a large coach pram.

In the front room, several logs glowed brightly in the fireplace. A pot of water bubbled away over the flames, children of varying ages playing close by. The high number of children arriving at hospital with severe burns and scalds meant that Alice frequently offered strong words of advice about the use of fireguards. It was one of the warnings that often fell on deaf ears, probably because finding the money for a guard was low down on the list of priorities for families who were worried about where their next meal might come from.

After eleven months in the post, the almoner was at least well practised in running through all of the necessary checks she needed to ensure that the financial information provided matched the family’s apparent means. She had also been trained to note down any evidence of harm to the children, bruising to the skin and other tell-tale signs of neglect, as well as any other issues that might negatively impact on a patient’s health. The rudimentary medical knowledge she had gained as a nurse with the VAD in a field hospital in Belgium helped her to discriminate between those injuries resulting from natural rough play and those of a more sinister origin.

The British Red Cross, recognising that the VADs had much to offer on their return to England, had offered scholarships to those willing to train as hospital almoners. Sent home after being injured from the fire resulting from the blast of a mortar bomb, and passionate about improving the living standards of the ordinary working people, Alice had jumped at the chance.

Back in 1916, when she had first arrived at the casualty clearing station in Belgium, unqualified and with no medical experience, she had only been allowed to carry out the most menial of chores, like cleaning floors and swilling out bedpans. The qualified nurses from Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), already battling for professional recognition, had resented the onslaught of hundreds of untrained women from middle-class homes. Inevitably, the grottiest of chores were directed towards the new arrivals.

Alice uncomplainingly cleaned up the stinking, putrid dead skin that had been scraped from the feet of soldiers suffering from trench foot. She swept up the discarded fragments of bloodstained uniform that nurses had pulled from infected wounds. She stoically hid her blushes when confronted with her first glimpse of a naked male.

Gradually the qualified staff recognised Alice’s dedication. As their attitude towards her softened and their appreciation grew, she was granted closer contact with injured soldiers. Like many of her contemporaries plunged into the aftermath of battle, she discovered that she possessed a natural ability to console. It wasn’t unheard of for Alice and the other VADs to lower themselves into the trenches to comfort dying soldiers, ignoring the roar of cannon fire and the smell of charred flesh. Mothers back in England found comfort in knowing that someone gentle had held their sons as they passed away.

Alice wrinkled her nose. There was a faint smell of drains, sour nicotine and something like old lard in the air – sometimes the dank smell inside the homes she visited was enough to make her retch – but the house was clean enough. The Redbourne children were whey-faced and snuffly with colds but there was no sign of fever or the dreaded influenza virus that had driven so many people to the Royal Free that winter. All of them were clothed and there was no sign of rickets among them. Neither were any of them possessed of that shrunken, unhealthy appearance that so worried the almoners whenever they came across it.

A small boy lay languidly on his tummy under a wooden clothes horse covered in linen cloth nappies and, incongruously, a white silk chemise. About a year or so old, his appearance was consistent with the description of Henry recorded in the Redbournes’ hospital file. Alice’s eyes lingered on his damp, flushed cheeks. With his head on his forearms, he looked close to dropping off, but healthy enough otherwise.

An older girl of around twelve years old was kneeling nearby, trying to field off blows from another young boy who was standing behind her. Around four years old, he alternated between slapping the top of her head and grabbing handfuls of her hair. He giggled when she pulled him over her shoulder and onto her lap, but then lashed out, slapping her in the eye when she tickled his midriff.

In light of what was to come, the child’s behaviour might have set some alarm bells ringing. As it was, the overall impression offered was one of need, but not destitution, or something graver. And yet somehow there was enough money left at the end of the week to finance nights out in the West End, and, so it seemed, luxury lingerie.

Alice scanned the room for a second time. In the corner, an older girl was sitting on a small sofa with her face turned towards the window. A sickly-looking toddler was perched on her knee. The conversation between Mrs Redbourne and Frank became increasingly loud and animated. By distracting the homeowner with his extravagant gestures, Frank was offering Alice the opportunity to carry out an inspection unhampered; one of the oft-used subterfuges employed by the almoners.

Even with the dust motes clinging to his beard, Frank looked fantastically conspicuous in the room. Alice and her colleagues had initially been perplexed at the idea of a man turning up whenever he felt like it to observe them at work, but his humour had put them quickly at ease. Beneath his buffoonery lurked a sharp mind and keen intuition, something he appeared keen to keep under wraps.

Quietly, Alice edged past the pair into the room. Frank shifted his weight subtly from one foot to the other to aid her passage. A ripple of interest at the arrival of yet another stranger rolled over the children. The young boy who was in the process of pinching his older sister sprang to his feet and walked over to her. ‘Hello,’ Alice said softly, crouching down in front of him. ‘What’s your name then?’

‘Jack,’ the boy answered and began fiddling with the sleeve of Alice’s cape. ‘You one of them busybodies?’

The almoner smiled then removed her hat and rested it on one knee, instantly softening her features. Some of Alice’s nursing colleagues were beginning to experiment with cosmetics, something that would have been considered vulgar before the war. When readying themselves for a night out, they would cajole her into darkening her lashes with a mixture of crushed charcoal and Vaseline, the more exuberant characters outlining their eyes in a dramatic sweep. Alice generally went make-up free when on duty, taming her long brown curls in a tight chignon at the back of her head. It was a style that gave her square jaw and high forehead prominence over her softest feature: her large, thickly lashed brown eyes. The resulting rather prim look came in useful when dealing with the least cooperative of patients. ‘Erm, I suppose some might say so.’

‘Mummy usually sends you lot packing.’

His older sister shifted around and gave a shake of her head. Alice pressed her lips together, eyes shining. ‘And who is this?’ she asked, kneeling in front of the young boy who was sitting on his older sister’s lap, bare knees dangling beneath a worn blanket. About two years old, the child regarded her shyly and buried his face in his sister’s chest. The latter planted a brief kiss on top of his hair. When she pulled away, her eyes remained downcast. The logs crackled in the grate as Alice stilled, waiting for an answer.

The girl, though wearing a morose expression, was pretty. Her cheeks were plump and prominent despite the thinness of her wrists, her eyes a feline green. After a few moments she met Alice’s gaze. ‘John,’ she mumbled, regarding the almoner with the sort of suspicion that anyone involved in social work quickly becomes accustomed to.

‘Hello, John,’ Alice said, with a brief touch to his knee. She looked up at his sister. ‘And you are?’

‘That’s Charlotte,’ Jack offered, stealing Alice’s hat from her knee and planting it lopsided on his own head. ‘She’s trouble, Mum says. Him’s Henry,’ he added, pointing to the young boy almost asleep on the floor. ‘And Elsa’s over there.’ The young girl sitting next to Henry chewed her lip and regarded Alice from beneath lowered lashes. Charlotte rolled her eyes and glared.

The tell-tale signs of a scabies infestation were visible along John’s forearm. Track-like burrows ran around his wrist where a mite had tunnelled into the skin, the tiny black dots of faecal matter visible around an angry rash. It was something Alice and the other VADs had often seen in the field hospitals; soldiers driven half-mad by the intense, irrepressible itch. The entire family would need to be treated with benzyl benzoate emulsion. ‘Not at school, Charlotte?’ Alice asked, in a precise but friendly tone.

It was a question designed to engage, rather than a genuine enquiry. The almoner had been taught specific interviewing strategies in training that helped her to disguise carefully planned interviews as casual chats, thereby gaining valuable insight into the living conditions of her patients: their relationships, finances, thoughts and fears. By examining individuals in the context of their social setting she was able to identify issues that might be impacting negatively on their health. Practical help honed to individual needs could then be offered, improving outcomes and the chances of a good recovery.

One way to encourage an interviewee to relax was to start a conversation with questions that were most easily answered, in much the same way as the devisers of written exams open with a problem easily solved. Since patients almost universally enjoyed talking about themselves, she learned that a readiness to listen, a keen interest in people and a sincere desire to help were all that was needed to encourage loose tongues.

‘I’m fifteen,’ the girl said, sounding offended. ‘I left ages ago.’

Alice nodded. ‘So are you working outside of the home now?’ The almoners knew it wasn’t unusual for older children to take a job so that they could contribute towards the family purse, even skipping school to do so. The income generated was often kept under wraps by families being assessed. Alice had been taught to be thorough in her questioning to uncover a true picture of a family’s finances.

‘Not really,’ Charlotte answered quickly. Her thin chilblained fingers worked continuously at the blanket on her brother’s lap, as if she had more to say. Alice waited, but the girl’s eyes flicked over to her mother and then her expression suddenly closed down. Her shoulders rounded further away so that the child on her lap wobbled and almost lost balance until she reached out and wrapped her arms around his waist.

Alice pressed her lips together, rescued her hat and rose to her feet. Over by the door, Frank’s charms were working a treat, Mrs Redbourne smiling up at him coyly. She barely seemed to notice when Alice slipped past. Behind her, Charlotte sat quietly, eyes watchful.

In the hallway, Alice hesitated. She stood in solitary silence for a few seconds, head cocked as if listening. After a moment she turned sideways to squeeze past the pram and then moved towards a closed door at the end of the hall. A soft thump stopped her in her tracks. There was a creaking sound, and then the door gave way, a pair of eyes peering through the crack.

After a short pause in which no one moved, the door was opened to reveal a fleshy, puffy-eyed man with a glossy sheen across his forehead. Alice strode towards him, thrust out her hand and smiled, as if a meeting had been planned between them. ‘You must be Mr Redbourne?’ she said. ‘Alice Hudson. Pleased to meet you.’

The man looked down at her and passed his tongue over his lips, then took her proffered hand. ‘You’ll be from the hospital,’ he said in an uncertain voice. ‘The wife could do without the added pressure,’ he added, when Alice confirmed her occupation. ‘We do what we can, but you can’t expect us to give what we don’t have.’

He followed her to the living room, but when his wife caught sight of him she shooed him away with her hand. ‘I thought you were at the market, George? Get going will yer, there’s things we need.’ Mr Redbourne pulled a pack of cigarettes from his pocket, took one into his mouth using his teeth, then, without another word, slipped out of the house.

When the front door clicked to a close, Alice entered the room he had just vacated. The back parlour was a dark room with a single bed in the centre, the wooden base held up by a pile of bricks at each corner. There was a bite to the air, the room colder than the street outside. A dozen shirts hung from a rope stretched diagonally across it, one end caught between the slightly open window and the other wedged between the top of a Welsh dresser and the wall.

Alice closed the door and peered into the nearby kitchen. Through the small window at the end of the room, a partly stone-flagged backyard was visible, a patch of bare earth beyond. An old lean-to housing the lavatory blocked what little winter light there was from entering the kitchen. There was no sign of running water; most working-class families were still filling buckets from a pump at the end of their street. The approaching twilight bathed the small area in shadows, the air fermenting with the smell of old dinners. With so many people living in the house the room was likely a place of much activity but, aside from a few black beetles scurrying across the floor and over the draining board, the overriding air was one of long abandonment.

The feeling of bleakness prevailed as the almoner made her way up the stairs. The rising wind caused a stray branch to tap rhythmically at the panes of the landing window, almost as if in warning.

It was a degree or two warmer upstairs than the kitchen had been but Alice shivered nonetheless as she ventured into the first bedroom. Bare, chipped floorboards bowed towards the middle of the room, the undulating surface and the sour tinge in the air adding to the general sense of unease.

Nothing stood out as being out of place. The bed, presumably belonging to Mr and Mrs Redbourne, stood low to the floor. Covered with a tatty, slightly stained tufted counterpane, it sagged drunkenly, as if in sympathy with the floor. Droopy curtains hung half-closed at the windows and an old leather suitcase stood up on end in front of a dressing table of dark wood, perhaps as a makeshift stool.

Back in the hall, another staircase wound itself over the first, leading to the second floor. Notes in the file showed that Mrs Redbourne had been specifically questioned about the empty rooms upstairs by the Head Almoner, Bess Campbell, who suspected that they may have been sub-let. Mrs Redbourne claimed that the space was uninhabitable due to damp walls and unstable floorboards, but the almoners had visited families who had carved living spaces into stables and coal bunkers; a loft space, however unsafe, would have been appealing enough to command at least a few shillings in rent from a desperate family.

Foreign voices and a clattering of footsteps drifted down through the floorboards, followed by a loudly slammed door. The window in the hall rattled in protest. Alice turned and stared at the cracked ceiling before moving further along the hall to a much smaller room.

Here, the entire floor was hidden by a horsehair mattress and an assortment of fraying blankets and clothes. In the twenty-six years since the first almoner was appointed in 1895, much intelligence had been gathered about the sort of secrets that could lay buried within families. As seekers of truth, the almoners knew that sometimes the sinister could be masked by a cloak of ordinariness. It was one of the reasons they were told not to hurry their home inspections, but to take their time, so that the hidden might somehow reveal itself.

Alice stood quietly in the doorway, running her eyes around the room. It was only at the sound of purposeful strides on the stairs that she finally turned around.

The face of Mrs Redbourne’s eldest daughter rose over the top of the banisters. The rustle of linen as the hem of Charlotte’s skirt brushed the stair beneath her feet seemed to whisper something other than her arrival. In the light of the upstairs hall, the shadows under the girl’s eyes became apparent, her cheeks speckled with a deep scarlet flush.

The almoner didn’t say anything; probably hoping not to attract attention from other family members. Instead, she took a step closer to the young woman and gave a reassuring smile. In that fleeting moment, the teenager’s desperation became evident.

After a wild glance behind her, Charlotte bit her bottom lip and then opened her mouth to speak. When no words came, Alice frowned and whispered: ‘Charlotte, are you alright?’

‘F-fine,’ the teenager stammered, the word at odds with her countenance. ‘But I-I think you should know –’ She stopped, then burst into tears. Alice’s fingers curled towards her palms, as if trying to encourage her to speak. ‘W-what I mean is, I should have said something sooner, but it’s too late now and …’, she faltered, her choked whispers stilted by the click of a door latch above.

Alice looked up. A middle-aged bespectacled gentleman wearing a long overcoat descended the stairs, a scarf knotted under his bearded chin. Charlotte whirled around and then scurried away, her long skirt fanning out behind her.

‘Good day, Madam,’ the man said in a heavy accented voice. Alice nodded and waited in the hall as the man traced Charlotte’s footsteps downstairs. The almoner’s expression was serious. As soon as she had crossed the threshold of the Redbourne’s home, something had struck a false note.

By the time she left, she later recorded in her case notes, it appeared as if something truly disturbing were about to unfold.

Chapter Two (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

The out-patient department, which annually receives over 40,000 cases, is at present conducted in the basement, which is ill-lighted and insufficient in accommodation … The hospital is situated in one of the poorest and most crowded districts of London …

(The Illustrated London News, 1906)

It was still dark when Alice woke two days later, on Monday, 2 January. Three years into the future, in 1925, the live-in staff of the Royal Free would move to purpose-built accommodation on Cubitt Street. The bedrooms of the Alfred Langton Home for Nurses were clean and comfortable, according to the Nursing Mirror, each one having ‘a fitted-in wardrobe, dressing table and chest of drawers combined. Cold water laid on at the basin and a can for hot water, and a pretty rug by the bed … everything has been done for the convenience and comfort of the nurses’.

As things were, the nurses managed as best they could in the small draughty rooms of the Helena Building at the rear of the main hospital on Gray’s Inn Road, where the former barracks of the Light Horse Volunteers had once stood. Huddled beneath the bedclothes, they would summon up the willpower and then dash over to the sink, the flagstone floor chilling their feet.

Alice’s breath fogged the air as she dressed hurriedly in a high-necked white blouse, a grey woollen skirt that skimmed her ankles and a dark cloche hat pulled down low over her brow. After checking her appearance in the mirror she left her room and made for the main hospital, where the stairs leading to her basement office were located. Outside, a brisk wind propelled young nurses along as they ventured over to begin their shifts, their dresses billowing around their calves. The skirts of their predecessors a decade earlier, overlong on the orders of Matron so that ankles were not displayed when bending over to attend to patients, swept fallen leaves along the ground as they went.

Just before the heavy oak doors leading to the hospital, Alice turned at the sound of her name being called from further along the road, where a small gathering was beginning to disperse. In among the loosening clot of damp coats and umbrellas was hospital mortician Sidney Mullins. One of the tools of his trade – a sheet of thick white cotton – lay at his feet, a twisted leg creeping out at the side.

Sidney, a fifty-year-old Yorkshire man with a florid complexion and a bald crown, save for a few long hairs flapping across his forehead, often strayed to the almoners’ office for a sweet cup of tea and a reprieve from his uncommunicative companions in the mortuary. Standing outside a grand building of sandstone and arches of red brick, he beckoned Alice with a wave of his cap then stood back on the pavement, rubbing his chin and staring up at one of the towers looming above him.

Shouts of unseen children filled the air as Alice took slow steps towards her colleague. She dodged a teenager riding a bicycle at speed on the way, and a puddle thick with brown sludge. ‘What is it, Sidney?’ Her eyes fell to the bulky sheet between them, from which she kept a respectful distance away.

The mortician pulled a face. ‘Forty-summat gent fell from t’roof first thing this morning,’ he said, scratching his belly. A flock of black-gowned barristers swept past them, their destination perhaps their courtyard chambers, or one of the gentlemen’s clubs nearby that were popular retreats for upper-middle-class men.

‘Oh no, how terribly sad,’ Alice said.

‘A sorry situation, I’ll give you that,’ Sidney said in his broad country accent. He rubbed his pink head and frowned up at the building. ‘But I just can’t make head nor tail of it.’

Alice grimaced. ‘Desperate times for some, Sidney. It’s why we do what we do, isn’t it?’

The mortician pulled his cap back on and looked at her. ‘Aye, happen it is. But I still can’t work it out.’

‘What?’

‘Well, how can a person fall from all t’way up there and still manage to land in this sheet?’

Alice gave a slow blink and shook her head at him. ‘Sometimes, Sidney …’

He grinned. ‘Oh, don’t look at me like that, lass. You’ve gotta laugh, or else t’pavements’d be full with all of us spread-eagled over them.’

Sidney recounted the exchange inside the basement half an hour later, Frank banging his barrelled chest and chuckling into his pipe nearby. The smell of smoke, damp wool and dusty shelves smouldered together in an atmosphere that would likely asphyxiate a twenty-first-century visitor, though none of its occupants seemed to mind the fug. ‘Never was a man more suited to his job than you, Sid,’ Frank said, gasping. ‘You were born for it, man. What do you say, Alex?’

Alexander Hargreaves, philanthropist, local magistrate and chief fundraiser for the hospital, was a tall, highly polished individual, from his Brilliantine-smoothed hair and immaculate tweed suit all the way down to his shiny shoes. A slim man in his late thirties, his well-groomed eyebrows arched over eyes of light grey. In the fashion of the day, an equally distinguished, narrow moustache framed his thin lips. There was a pause before he answered. ‘I prefer “Alexander”, as well you know, Frank,’ he said, without looking up from the file on his desk. ‘In point of fact,’ he added in a tone that was liquid and smooth after years of delivering speeches after dinner parties, ‘I don’t happen to think there’s anything remotely amusing about mocking the dead.’

The walls behind Alexander’s desk were lined with letters thanking him for his fundraising efforts, as well as certificates testifying to the considerable funds he had donated to various voluntary hospitals over the years. Framed monochrome photographs of himself posing beside the equipment he had managed to procure, developed in his own personal darkroom, were displayed alongside them.

Sidney’s podgy features crumpled in an expression of genuine hurt. Years in the mortuary had twisted his once gentle humour out of shape until it was dark, wry and, to some, wildly offensive, but his respect for the gate-keeping role he played between this life and the grave never wavered. ‘Right,’ he said a little forlornly, clapping his hands on his podgy knees. ‘I reckon I’d best get back to the knacker’s yard.’

Alexander’s nostrils flared. Frank arched his unkempt brows. ‘Come on, Alex, where’s your sense of humour?’

‘Lying dormant for the time being,’ came Alexander’s reply. ‘To re-emerge whenever someone manages to display some wit.’

Stocky office typist Winnie Bertram blew her nose into a hanky and tucked it back into the handbag that rarely left her lap. ‘God rest his soul,’ she said, her reedy, wavering voice momentarily cutting through the office banter.

Alexander glanced up from his work. ‘Are you coping, Winnie?’

Winnie adjusted the black silk shawl she was wearing around her shoulders, the one she had worn religiously since Queen Victoria had been interred next to Prince Albert in Windsor Great Park more than two decades earlier. ‘Not particularly, dear, no,’ she said, straightening her spectacles with a mottled hand.

Winnie could be relied upon to mourn every loss the hospital notched up, even if the first she had heard of the patient was after they’d departed. She too was in the ideal job in that regard, especially with Sidney keeping her abreast of every last gasp, choke and coronary going on above them.

‘You look tired,’ Alexander pressed gently. ‘Perhaps you should consider spending the day at home?’

Winnie patted down her short grey hair and gave Alexander a wan smile. ‘I’ve been tired since 1890, dear. Don’t worry about me, I’ll soldier on.’

Alice rolled her eyes. Witnessing the aftermath of war had left her with a sense of urgency to improve the lives of society’s most unfortunate, as well as a lack of patience for those with a tendency to complain about trifling issues.

She herself recognised her good fortune, having enjoyed a largely happy childhood. Quick intuition made her the ideal student and as she grew older, she delighted in the new opportunities becoming available to women. Influenced by her parents, who were both pacifists and active peace campaigners, Alice became aware of society’s ills at an early age. She and her elder brother, Frederick, sat quietly in the corner of the sofa during the meetings of the National Peace Council – a body coordinating smaller groups dedicated to furthering the cause of non-violent opposition across Britain – that took place in the living room of their Clapham home.

In later years Alice became brave enough to interject, shaping the skills of negotiation and the moral compass that were to guide her as she tended to wounded soldiers on the battlefield, the ear-splitting crack of shell-fire in the distance, plumes of gas looming high above her head.

‘But I don’t understand why they had to invade!’ thirteen-year-old Alice had burst out passionately, in response to an argument about the Austro-Hungarian annexing of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Her father glanced at her tenderly. ‘The Austrians are flexing their muscles, love. They want to ensure their empire is taken seriously. We’ll see where their flag-waving nationalism gets them soon enough, I suspect.’

‘War, in the Balkans and beyond, you mark my words,’ one of the men, a Quaker, answered hotly, causing a great deal of muttering and concern on the faces of those present.

A hiss of steam from the old boiler caught everyone’s attention. In the lull that followed, Alice asked Frank if he was ready to join her in outpatients. She was scheduled to spend the day conducting assessments on some of those waiting, all the while keeping an eye out for cases of fraud. It was an information-gathering exercise, and the ideal opportunity for Frank to gain a sense of her work.

‘I’ve decided to carry on with my review of the paperwork down here this morning, dear Alice,’ Frank said, checking his pocket watch and slipping it back into his waistcoat. ‘Besides, you females are so much better with the ailing than us men.’

‘But I have juggled everything around, as you asked me to. I haven’t been through the inpatients lists yet, and I need to organise wigs and prosthetics for several patients.’

‘Don’t you worry about that,’ Frank said. There was a hopeful glance from Alice, before he continued. ‘It will still be here when you get back.’

‘That doesn’t sound particularly fair,’ Alexander offered from the other side of the room.

‘No,’ Alice said, turning to him. ‘But then some men believe a woman’s sole purpose is to bend to their every whim. In fact, I suspect that some would prefer it if we didn’t exist at all.’

‘Ha! Not true, if indeed the lady is referring to me,’ Frank said. He stuck out the tip of his tongue, removed a flake of tobacco and planted it back in his pipe. ‘I love the female of the species. Fascinating creatures.’

Alice grimaced, grabbed her notepad and pen, and left the office with a cold glance towards her colleague.

When the first almoner, Mary Stewart, took up her post at the Royal Free in 1895, for which she was paid a modest annual salary of ?125, she was allocated a small corner of the outpatients’ department to work from. Visitors to her ‘office’ perched themselves on the edge of a radiator in the dark, airless space, a thin screen partitioning them from the view of the throng of patients waiting to be seen.

Six years later and a few miles away to the south, the first female almoner of St George’s Hospital, Edith Mudd, was to carry out her duties from a screened-off area in the recovery room next to the operating theatre. She got on with the job conscientiously, doing her best to concentrate despite the activity across the room as patients came round after anaesthesia. Since the almoners were used to moving around between London hospitals to cover each other’s shifts and gain wider experience, they quickly learned to adapt to unusual working environments; one of Edith Mudd’s successors at St George’s managed to run a fully functioning almoners’ office from one of the hospital’s bathrooms.

It was in a similarly small space known as the watching room that Alice seated herself in the outpatients department; somewhere from which she could keep an eye on the comings and goings with a degree of discretion. It was just before 9 a.m. but already there were few gaps on the wooden benches that were arranged in tight rows across the large atrium. Incessant rain pelted the small recessed windows of the double doors at the entrance to the building, the wind penetrating the gap beneath the doors with a ferocious whistle.

After arranging her notepad and pen on a small desk, Alice interviewed a woman who was convinced that her daughter’s knitted woollen knickers had caused a particularly nasty outbreak of intimate sores. ‘Well, what else could it be?’ the woman asked Alice earnestly, her overweight daughter cringing behind a curtain of long greasy hair beside her. The almoner suggested that the woman should return home, then discreetly booked her daughter into the VD clinic.

Her next interviewee was a charlady who was more in need of something to wear on her feet than medical treatment. When Alice told the woman that she would source some charitable funds to buy her a pair of shoes, she was rewarded by a wide, gap-toothed smile. The almoner glanced up and narrowed her eyes between interviews, checking on the comings and goings beyond the screens.

One of the most enjoyable and rewarding aspects of an almoner’s work was being able to witness the benefit of their interventions. When Alice presented her next visitor – an elderly watchman suffering with eczema whose sore hands had blistered after spending several cold nights in the watchman’s shelter – with a pair of cotton gloves, he danced a little jig in delight, drawing applause from the patients waiting on the other side of the screen.

The day passed productively; four full financial assessments completed, several patients booked in with the relevant doctors and one fraudulent claimant given his marching orders.

At a little before 4 p.m., after securing the patient files in a tall cabinet, Alice ventured out into the main reception area.

‘Hello again,’ she said with a nod to the elderly couple who were sitting together and holding hands in the far corner of the outpatients department waiting area. Ted and Hetty Woods had spent almost every day of the last week huddled side by side in the same spot, their few belongings stowed in a dog-eared bag at Ted’s feet.

‘Hullo, Miss,’ Ted said as his pale-blue eyes fixed on Alice’s face. Mrs Woods, a plump woman with hair of faded copper, gave her a tired but cheerful smile. The lines on her face were deep, the upward edges of her mouth suggesting a character that was determined to remain hopeful, despite all the difficulties that were thrown her way.

‘We spoke about you both perhaps spending a day or two at home, didn’t we?’ Alice said, crouching down in front of them and resting a gloved hand on Ted’s knee. She was due to meet with Dr Peter Harland, the physician who had treated little Henry Redbourne’s bad chest, at the end of his shift. Their meeting had been arranged to exchange notes on other chest clinic patients, but the list of questions pinned to the front of the file in the almoners’ office reflected Alice’s hope of steering the conversation towards the Redbourne family.

The young woman, Charlotte, had said little during their welfare check on the family, but working closely with families had honed Alice’s intuition. Quickly, she had learned to distinguish between the troubles that blighted most families from time to time and those rising from something more sinister; it was a sort of occupational sixth sense.

‘We’re all at sixes and sevens at home, love. We’re alright here, if it’s all the same to you.’ Ted doffed his cloth cap, but anxiety lay beneath the civility. The skin on his face was chapped and his lips were pale and translucent, but his thin hair had been carefully combed and his clothes were clean and well pressed. Mrs Woods was similarly well groomed and yet, despite the rose water she was dabbing on her wrists and her well-scrubbed pink skin, a peculiar smell rose from beneath her clothes.

‘And you, Mrs Woods? How are you?’

‘Fine, duck. Lovely, thank you.’ Alice’s eyes lingered on the elderly woman, her brow furrowed. She had visited the couple at home months earlier after Ted’s treatment for a severe leg ulcer. With a single room in a three-storey boarding house, they were better off than some, but the mould on the walls and lack of running water meant that it was far from comfortable.

Alice sighed, glancing across the large atrium. Two doctors wearing white laboratory coats stood whispering near a set of fabric screens, nurses bustling past them into the anterooms. A few feet away, another nurse stood in front of a plump elderly woman, trying to help her onto her feet.

An unpleasant musty smell prevailed in the department, overlaid with a hint of carbolic soap; a consequence of every available space being filled with the poor. Numerous ill-clad elderly locals huddled together with threadbare blankets draped over their knees, several in the grip of severe coughing fits. It was likely that more than half of those filling the space weren’t interested in seeing a doctor. If there was a chill in the air it wasn’t unusual for the almoners to find the outpatients department thronging with people like Ted and Hetty, hopeful of passing the time in a place that was warmer and less dreary than their homes.

Alice reached into her handbag and pressed a coin into Ted’s frail hand. She had learned in training and keenly felt that it was her duty to remember the person behind the illness. She had been taught that there was little point in administering medicine to the sick only to discharge them back to a life of near destitution. Sometimes the smallest of interventions was all that was needed to relieve hardship and change lives.

‘I think perhaps –’ Alice began, but broke off at the sound of a shout. Several patients started and turned their heads towards a heavily pregnant woman who was standing by one of the curtained examination cubicles and yelling at a stocky man wearing labourer’s scruffs.

Angling herself sideways on so that she could reach him around her considerable bump, the woman landed a punch on the man’s chest and another on the side of his head. Spots of blood glistened from the resulting scratch on his cheek, and another just above his lip. ‘Will you leave off me, woman!’ the man yelled breathlessly, doing his best to dodge her blows while coughing explosively.

Alice gave Ted’s leg a quick pat and rose to her feet. She wove purposefully around the packed rows of wooden benches, the pregnant woman gesticulating and shouting as she made her way over. ‘I swear you’ve done it now, Jimmy!’ the woman screamed.

‘Excuse me,’ Alice said firmly, seizing the scruffy man’s arm. ‘Nurse,’ she called out, angling her head towards the treatment area. Several patients stared at the smartly dressed woman who had suddenly appeared, their mouths open in hushed, awed silence.

‘Sit down, please,’ she ordered the man, who was still coughing and frantically gasping for air. She motioned him away with a tiny flick of her head, her expression stern. Obediently, he backed away and collapsed onto a nearby seat.

A nurse emerged from one of the cubicles. Her eyes flicked from Alice to the pregnant woman, who was still trying to attack the heavy-set man, and then she hurried over to help. ‘Stay outta this, Miss,’ the expectant mother shouted to Alice. ‘Someone needs to sort ’im out, once and for all.’

‘No one is sorting anyone out, thank you,’ Alice said, her voice carrying across the hall. ‘I’ll deal with this.’

‘He’s a filthy lying hound!’ the woman yelled, spittle spilling out from the edges of her mouth.

‘Be that as it may, he’s now our patient,’ Alice returned, her voice low and steady. Behind her, the nurse handed the man, who was now coughing up blood, a handkerchief. ‘If you want to come back and see me later today, I’m happy to talk things through with you. But for now, please, I’d like you to leave.’

‘You’ll pay for this, Jimmy!’ the woman screamed over Alice’s shoulder, as the nurse led him away. ‘I hope you cough up your guts and strangle yourself with ’em,’ she added, before turning on her heel and waddling to the door.

Alice pulled down the cuffs of her blouse, straightened her hat and gave several still-gawping patients a reassuring smile. The almoner often needed to draw on every ounce of diplomacy she could muster to deal with the loud confrontations that sometimes broke out in the outpatients department.

The man was still coughing when Alice joined him in the watching room. ‘She’s agitated ’cos I’m not earning what I-I used to on account of this cough,’ he told Alice in a thick Irish accent. ‘And what with the baby soon to join us –’

Alice opened a new file and jotted down some notes while Jimmy spoke. A thirty-five-year-old labourer, Jimmy had sailed for England from Ireland a year earlier looking for work. He managed to find employment on the Wembley Park site, where work was under way preparing the ground for a new restaurant to be built near the planned new sports stadium, but had not yet managed to save enough to cover the cost of a deposit on his own lodgings.

Alice managed to elicit that he had spent most nights sleeping with three other workmen in a small shed on site, while his pregnant wife camped out on her parents’ sofa. Waking in the same damp clothes he had worked in the previous day, his health had worsened through the winter. ‘’Tis a fine place here though,’ Jimmy said, when Alice confirmed that his meagre earnings and imminent dependant qualified him for entirely free treatment at the hospital. ‘And you’re a fine woman, so you are,’ he gasped, after she told him that he’d been booked into the chest clinic. A deep hacking cough issued from his lungs. He rubbed his red-rimmed eyes, watery with the strain of coughing, and said: ‘Too fine to be wasting your time helping a vagrant like me.’

As the almoner made her way back across the atrium, Hetty Woods nudged her husband with her elbow. When she neared, Ted signalled to her. ‘We was wondering, Miss Alice. Do you think you might have the opportunity to visit our daughter, Tilda? She’s expecting but her husband won’t let us near the place. He’s got some sort of hold over her, I think. We haven’t seen her for months. But my Hetty thinks that if anyone can sort them out, you can.’

Alice glanced over to the double doors, where another line of people were waiting to file inside. When temperatures plummeted, as they had in London in the last twenty-four hours, it was difficult to impose some order on the chaos reigning in outpatients. The doctors found the crowded conditions near impossible to work in, but the worsening storm and poor visibility at least provided her with an excuse to grant the most destitute a temporary reprieve.

‘I will see what I can do in the next few days,’ Alice told the couple, after noting down their daughter’s address.

‘Don’t go after six though, duck,’ Hetty said warningly. ‘That’s when our son-in-law gets home.’

The almoner nodded. ‘I cannot promise anything, but I will try.’

Ted and Hetty watched Alice as she headed off for her meeting with Dr Harland, their rheumy eyes watery with gratitude.

Chapter Three (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

The almoner is a general practitioner in social healing. It is the almoner whose job it is to deal with the personal difficulties and troubles of the patient … the constructive side of the social work done by the almoner seems to know no limits.

(The Scotsman, 1937)

From its earliest days as an apothecary, doctors from the Royal Free went out into the community to treat patients who were too ill to leave their homes, or rose in the early hours to meet them at the hospital. ‘As there were no telephones,’ explained Dr Grace de Courcy, a medical student in 1894, ‘if an emergency arose at night and the resident required assistance he would go into the street and take a hansom cab or a growler to the house of the surgeon or physician in charge of the ward to bring him back.’

Dedicated to their patients and uncomfortable with the idea of their private lives being examined, medical staff at the Royal Free had initially been reluctant to share any information with the almoners. For some, the whole idea of conducting financial assessments on the sick was repugnant. Sir E. H. Currie complained to a reporter for the London Daily News in 1904 that vetting patients using ‘special detectives’ was ‘a scandal’. Currie ‘strongly condemned’ the use of inquisitorial methods to ‘denounce’ well-off patients. ‘What possible good can one woman investigator do?’ he argued. ‘It is ridiculous.’

Mr Rogers, a secretary from the London Hospital, defended the appointment of an almoner who was to ‘watch in the receiving rooms for cases of imposition’. The secretary stated that local doctors running private practices had accused the hospital of ‘robbing their profession’ by treating patients who ‘they had personally seen … driving to hospital in their own carriages’.

Like his predecessors, Dr Peter Harland was another of those people who subscribed to the view that any sort of surveillance of the private lives of others was a disagreeable pastime. He was waiting at the top of the stairs leading to the almoners’ basement office when Alice arrived. ‘I’m so sorry, doctor. Have you been waiting long?’

‘A minute or so.’ There was no reproof in his voice, but his features were strained.

Alice led the way down the dimly lit stairs, stopping before a sturdy-looking oak door inset at eye-level with a small barred window. Dr Harland waited silently as she opened the door to the office, where arrow-slit windows high up across one wall overlooked the sodden grey pavement of Gray’s Inn Road. The window sills provided neat cubby holes for reference books and medical journals, the heavy tomes blocking much of the natural light.

Before the fires were lit by the caretaker each morning, the almoners’ office lay silent, the stillness broken only by the rumble of underground trains beneath them. Now, the room was bustling with activity. Frank was seated at the nearest desk, taking ledgers one by one from a small pile and checking them against a list of the hospital’s assets. Alexander was kneeling on the floor beside a solid leather trunk and setting a trap for the mice that emerged at night to nibble the edges of his financial reports. He fumbled with the steel mechanism with a harried air, his handsome features twisted and pink with annoyance. In the far corner, Winnie sat behind her typewriter, her habitual anguished frown in place.

At the opposite end of the office, the Lady Almoner, Bess Campbell, was busy preparing lists for a post-New Year party; a get-together for those acquaintances who had missed out on the New Year’s celebration that had taken place in her considerable residence in Kensington. Miss Campbell, a woman with a flair for combining dynamic guests with those of a quieter nature so that everyone felt at ease, had a calendar packed with social events, dances and dinner parties.

She was a slim woman in her late forties, with greying shoulder-length hair and sharp but pleasant features. An accomplished and formidable character, she had a love of fine clothes and an air of authority, but she was also possessed of a natural humility, an essential quality in someone working so closely with the poor.

Like the majority of her colleagues, she had been selected from a class superior to those she served, the appointing committee believing that only someone gifted with eloquence could suitably advocate for the working class, who were generally less able to express themselves.

Each member of staff glanced up as Alice entered. At the appearance of Dr Harland, Alexander got to his feet and brushed down his trouser legs. Puffing absently on his pipe, Frank merely jutted out his chin. Miss Campbell beamed. ‘Peter, my dear, how are you?’

‘Too busy to be here. And you?’ The doctor’s expression settled as far into solicitousness as it ever went, though his face, all blunt lines and irregular angles, retained its slightly grumpy expression. About six inches taller than Alice, at just under five feet eleven, he was a tall man, sturdy and strong. In his mid-thirties, his square face was framed by a crop of thick curly black hair, his jaw displaying the hint of a beard.

‘Well, it’s most generous of you to spare some time for us, isn’t it, Alice? And I’m splendid, thank you.’ Miss Campbell ran the office with a regimen as strict as the fiercest sisters on the wards above her, but there were times when her staff caught a glimpse of the compassion she usually reserved for patients. When Alice had returned to the office after discovering the bodies of Molly and her infant son, Miss Campbell had been the first to her feet, steering Alice with tenderness towards her chair. Within minutes she had pressed a hot, disturbingly sweet cup of tea into one hand and a vinaigrette of smelling salts into the other. Alice was to take her final exam in social work the next day, but after what had happened, she told her boss that she was tempted to withdraw. ‘I’m not suited to this sort of work,’ she told Miss Campbell mournfully, after everyone else had gone home.

Miss Campbell had reached across the desk and taken Alice’s hand in her own. ‘If you’re not suited to it, my dear, I don’t think any of us are.’

‘If only I’d acted sooner,’ Alice had burst out, pulling her hands away to cover her cheeks. She shook her head. ‘I knew something wasn’t right. I should never have left Molly alone for so long.’

Miss Campbell scoffed gently. ‘Would not the world be a finer place if only we were all possessed with blessed foresight?’ She paused. Alice dropped her hands and looked at her. The Lady Almoner levelled her gaze. ‘Alice, you need to accept that we all have limitations, and that includes you. You’re not responsible for every vulnerable waif and stray in London, you know. But you have more empathy and intuition than almost anyone else I know. So you’ll go tomorrow and take your exam and then you’ll return here to carry on with your work.’

Alice’s eyes pooled with tears. ‘But I’ll fail, just like I failed Molly.’

‘Then you shall take it again,’ Miss Campbell had said with a note of finality and a short sharp squeeze of Alice’s hand.

At her desk, Alice removed her hat and gloves and tucked them into a drawer. ‘Would you like a cup of tea before we get started, doctor?’

Dr Harland nodded as he drew up a chair and sat at the end of her desk. From across the office, Frank began to cough theatrically. ‘I take it you would like one too, Frank,’ Alice said, moving towards the boiler with weary amusement.

‘I am parched, now you mention it.’

Winnie got to her feet and made efforts to convince Miss Campbell, who had declined Alice’s offer, that it would be wise to keep hydrated. She then hovered behind Alice and warned her of the perils inherent in carrying out any activity involving boiling water. ‘I have everything under control, Winnie, thank you,’ Alice said with impatience.

The almoner warmed the office teapot using the water bubbling away in a large pot on top of the boiler. After setting a few mismatched cups on top of an empty desk, she swirled the hot water around the pot and emptied the vestiges into the large porcelain sink in the corner of the room. She scooped a caddy spoon of tea leaves inside, the soothing simplicity of the act at odds with the concerns that had been swirling in her mind over the last couple of days, since visiting the Redbournes’ house.

Outside, there was a temporary reprieve from the rain. A shaft of winter sunlight shone through the grime-covered, half-blocked windows, temporarily transforming the gloomy office from dungeon to a bright, airy place. The fug of ink, damp paper and coal in the air lifted momentarily, returning less than a minute later when the sun disappeared behind a cloud.

‘What have I told you?’ Frank roared a minute later, jumping to his feet. ‘Milk in last, not first!’ He strode towards Alice, pipe in hand, his grizzled features screwed up in mock disgust. ‘If you were my wife I’d ask you to tip that away and start again.’