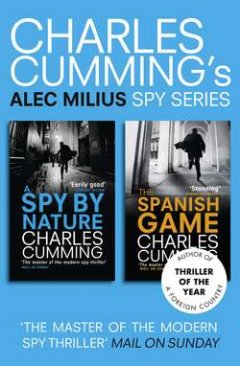

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Àâòîð:Charles Cumming

» Âñå êíèãè ýòîãî àâòîðà

Òèï:Êíèãà

Öåíà:1017.19 ðóá.

ßçûê: Àíãëèéñêèé

Ïðîñìîòðû: 357

ÊÓÏÈÒÜ È ÑÊÀ×ÀÒÜ ÇÀ: 1017.19 ðóá.

×ÒÎ ÊÀ×ÀÒÜ è ÊÀÊ ×ÈÒÀÒÜ

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Charles Cumming

This ebook omnibus edition brings together Charles Cumming’s two classic Alex Milius novels, also offering readers a sample of his following novel The Trinity Six.A SPY BY NATUREAlec Milius is young, smart, ambitious and comfortable with deceit. So when a chance encounter leads him to MI6, Alec thinks he’s landed the perfect job for his talents. But working alone, relying on instinct, he’s soon spinning a web of deception that has him caught between his new masters and powerful opponents. For in his new line of work the difference between the truth and a lie can be the difference between life and death. And Alec is having trouble telling them apart …THE SPANISH GAMEAlec Milius quit the spying game six years ago – or so he thought.Living in exile in Madrid, he is lured back into a brutal world of lies and deception by the mysterious disappearance of a prominent politician. Forced to work alone, without the support of his former masters in London, Alec comes face to face with the nightmare of modern terror. And this time there's no-one to call for help…

Charles Cumming

Alec Milius Spy Series: Books 1 and 2

A SPY BY NATURE and THE SPANISH GAME

Copyright (#uf33ecc6f-77b6-56de-9bc7-ab9c13bed6f7)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2011

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2011

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007432967

Version: 2014-12-16

Contents

Cover (#u4ff040ef-e238-5c12-8123-f52a60ab40b5)

Title Page (#uf697307a-7700-55dd-ad4f-678f6acfc68b)

Copyright

A Spy By Nature (#ulink_44b747e0-c09b-5565-8a76-4a27d0b51b7b)

The Spanish Game (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract from A Foreign Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

By Charles Cumming

About the Publisher

CHARLES CUMMING

A Spy By Nature

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarpercollinsPublishers

77-85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This HarperCollins edition first published 2011

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Books Ltd. 2001

Copyright © Charles Cumming 2001.

Cover layout design © HarperCollins Publishers 2011

Cover photographs © Silas Manhood

Extract from The Sportswriter copyright © Richard Ford.

Published in Great Britain by Harvill Press 1986

Extract from The Uses of Enchantment copyright © Bruno Bettelheim.

Published in Great Britain by Thames & Hudson 1976

Extract from Rabbit Redux copyright © John Updike.

Published in Great Britain by Andr? Deutsch 1972

‘Fake Plastic Trees’ Words and Music by Thom Yorke, Edward O’Brien, Colin Greenwood, Jonathan Greenwood and Philip Selway © 1994 Warner/Chappell Music Ltd., London W6 8BS. Reproduced by permission of International Music Publications Ltd.

Charles Cumming asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007416912

Ebook Edition © July 2011 ISBN: 9780007416905

Version: 2014-12-15

Dedication

For my wife, Melissa

Contents

Cover (#u3107c826-d38b-5980-a3a0-273f646dc5a8)

Title Page (#u89b4e5d2-2592-5554-aa3f-c29c91d4a389)

Copyright (#u7b851e55-c59b-5910-bd09-42c2ce1fc8a9)

Dedication (#u9f430ced-760b-5a3b-bc02-3cd908962b25)

Epigraph (#ua5024516-7262-5831-a15e-b1b52b4920c1)

Author’s Note (#u0a810879-1c18-5730-ba33-04312621fcd3)

Part One: 1995 (#u3af65b48-479f-5253-8430-ff36d356c9e7)

One: An Exploratory Conversation (#u6356ef49-5695-500a-bf30-6656c20e9c6f)

Two: Official Secrets (#ud67d6180-53bb-542a-b693-1c41823d7ce0)

Three: Tuesday, 4 July (#ubb09690e-0ba6-505f-9740-a2551067dd75)

Four: Positive Vetting (#ua0443f77-ea7d-5f33-8672-0e3d0332f8f9)

Five: Day One/Morning (#u4c33aede-693a-556b-89de-1f410dbdd412)

Six: Day One/Afternoon (#ub511177e-bc95-5ba3-a044-dd8f647f2298)

Seven: Day Two (#uef1cb20c-ba6c-5c12-9fc5-be938829c890)

Eight: Pursuit of Happiness (#ub28940d4-ad6d-56f4-b9a3-0afd11dc45b0)

Nine: This is Your Life (#uab6a2cc0-b66c-5d8c-ab4a-60cb96d85618)

Ten: Meaning (#u8e99dc6a-e13c-5850-ae03-bdb8270e0b9b)

Part Two: 1996 (#u10f12d09-1124-5560-8927-1ee88675717e)

Eleven: Caspian (#u234e7ae2-98a5-5f08-ad29-80ed0436f149)

Twelve: My Fellow Americans (#udbe1f139-966f-5f76-a970-af8d3d636f83)

Thirteen: The Searchers (#u1abd8b07-e21f-5b84-9a9a-84c526700521)

Fourteen: The Call (#u37010295-68c3-5d11-9549-075082512217)

Fifteen: Tiramisu (#u555f31aa-9c9e-5966-9c3b-c0b6b1ba2ccf)

Sixteen: Hawkes (#u793b5f6c-2f90-533a-bd9a-0a9e1ecf5e61)

Seventeen: The Special Relationship (#u49ca25ee-fecb-5018-9be8-9e181ea448fb)

Eighteen: Sharp Practice (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen: Seize the Day (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty: Creating Justify (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One: Being Rick (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two: Plausible Deniability (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Three: The Case (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Four: Final Analysis (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: 1997 (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Five: The Lure (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Six: The Approach (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Seven: The Sting (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Eight: Cohen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Nine: Truth Telling (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty: Limbo (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-One: Baku (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Two: End of the Affair (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Three: Caccia (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Four: Think (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Five: Fast Release (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Six: West (#litres_trial_promo)

Epigraph

I remember, in fact, the Lebanese woman I knew at Berkshire College saying to me, after I told her how much I loved her: ‘I’ll always tell you the truth, unless of course I’m lying to you.’

Richard Ford, The Sportswriter

Author’s Note

Were the events of this story entirely true, they would inevitably breach clauses in The Official Secrets Act. Nevertheless, members of the intelligence community both in London and in the United States may find that they catch their reflection in the account which follows.

–C.C.

London, 2001

PART ONE

1995

If we hope to live not just from moment to moment, but in true consciousness of our existence, then our greatest need and most difficult achievement is to find meaning in our lives.

—Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment

ONE

An Exploratory Conversation

The door leading into the building is plain and unadorned, save for one highly polished handle. No sign outside saying FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE, no hint of top brass. There is a small ivory bell on the right-hand side, and I push it. The door, thicker and heavier than it appears, is opened by a fit-looking man of retirement age, a uniformed policeman on his last assignment.

‘Good afternoon, sir.’

‘Good afternoon. I have an interview with Mr Lucas at two o’clock.’

‘The name, sir?’

‘Alec Milius.’

‘Yes, sir.’

This almost condescending. I have to sign my name in a book and then he hands me a security dog tag on a silver chain, which I slip into the hip pocket of my suit trousers.

‘Just take a seat beyond the stairs. Someone will be down to see you in a moment.’

The wide, high-ceilinged hall beyond the reception area exudes all the splendour of imperial England. A vast panelled mirror dominates the far side of the room, flanked by oil portraits of grey-eyed, long-dead diplomats. Its soot-flecked glass reflects the bottom of a broad staircase, which drops down in right angles from an unseen upper storey, splitting left and right at ground level. Arranged around a varnished table beneath the mirror are two burgundy leather sofas, one of which is more or less completely occupied by an overweight, lonely-looking man in his late twenties. Carefully, he reads and rereads the same page of the same section of The Times, crossing and uncrossing his legs as his bowels swim in caffeine and nerves. I sit down on the sofa opposite his.

Five minutes pass.

On the table the fat man has laid down a strip of passport photographs, little colour squares of himself in a suit, probably taken in a booth at Waterloo station sometime early this morning. A copy of The Daily Telegraph lies folded and unread beside the photographs. Bland non-stories govern its front page: IRA hints at new ceasefire; rail sell-off will go ahead; 56 per cent of British policemen want to keep their traditional bobbies’ helmets. I catch the fat man looking at me, a quick spot-check glance between rivals. Then he looks away, shamed. His skin is drained of ultraviolet, a grey flannel face raised on nerd books and Panorama. Black oily Oxbridge hair.

‘Mr Milius?’

A young woman has appeared on the staircase wearing a neat red suit. She is unflustered, professional, demure. As I stand up, Fat Man eyes me with wounded suspicion, like someone on his lunch break cut in line at the bank.

‘If you’d like to come with me. Mr Lucas will see you now.’

This is where it begins. Following three steps behind her, garbling platitudes, adrenaline surging, her smooth calves lead me up out of the hall. More oil paintings line the ornate staircase.

Running a bit late today. Oh, that’s okay. Did you find us all right? Yes.

‘Mr Lucas is just in here.’

Prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet.

A firm handshake. Late thirties. I had expected someone older. Christ, his eyes are blue. I’ve never seen a blue like that. Lucas is dense boned and tanned, absurdly handsome in an old-fashioned way. He is in the process of growing a moustache, which undercuts the residual menace in his face. There are black tufts sprouting on his upper lip, cut-rate Errol Flynn.

He offers me a drink, an invitation seconded by the woman in red, who seems almost offended when I refuse.

‘Are you sure?’ she says, as if I have broken with sacred tradition. Never accept tea or coffee at an interview. They’ll see your hand shaking when you drink it.

‘Absolutely, yes.’

She withdraws and Lucas and I go into a large, sparsely furnished room nearby. He has not yet stopped looking at me, not out of laziness or rudeness but purely because he is a man entirely at ease when it comes to staring at people. He’s very good at it.

He says, ‘Thank you for coming today.’

And I say, ‘It’s a pleasure. Thank you for inviting me. It’s a great privilege to be here.’

There are two armchairs in the room, upholstered in the same burgundy leather as the sofas downstairs. A large bay window looks out over the tree-lined Mall, feeding weak, broken sunlight into the room. Lucas has a broad oak desk covered in neat piles of paper and a framed black-and-white photograph of a woman whom I take to be his wife.

‘Have a seat.’

I drop down low into the leather, my back to the window. There is a coffee table in front of me, an ashtray, and a closed red file. Lucas occupies the chair opposite mine. As he sits down, he reaches into the pocket of his jacket for a pen, retrieving a blue Mont Blanc. I watch him, freeing the trapped flaps of my jacket and bringing them back across my chest. The little physical tics that precede an interview.

‘Milius. It’s an unusual name.’

‘Yes.’

‘Your father, he was from the Eastern bloc?’

‘His father. Not mine. Came over from Lithuania in 1940. My family have lived in Britain ever since.’

Lucas writes something down on a brown clipboard braced between his thighs.

‘I see. Why don’t we begin by talking about your present job. The CEBDO. That’s not something I’ve heard much about.’

All job interviews are lies. They begin with the r?sum?, a sheet of word-processed fictions. About halfway down mine, just below the name and address, Philip Lucas has read the following sentence:

I have been employed as a Marketing Consultant at the Central European Business Development Organization (CEBDO) for the past eleven months.

Elsewhere, lower down, are myriad falsehoods: periods of work experience on national newspapers (‘Could you do some photocopying please?’); a season as a waiter at a leading Genevan hotel; eight weeks at a London law firm; the inevitable charity work.

The truth is that CEBDO is run out of a small, cramped garage in a mews off Edgware Road. The kitchen doubles for a toilet; if somebody has a crap, no one can make a cup of tea for ten minutes. There are five of us: Nik (the boss), Henry, Russell, myself, and Anna. It’s very simple. We sit on the phone all day talking to businessmen in central–and now eastern–Europe. I try to persuade them to part with large sums of money, in return for which we promise to place an advertisement for their operation in a publication known as the Central European Business Review. This, I tell my clients, is a quarterly magazine that enjoys a global circulation of four hundred thousand copies, ‘distributed free around the world.’ Working purely on commission I can make anything from two to three hundred pounds a week, sometimes more, peddling this story. Nik, I estimate, makes seven or eight times that amount. His only overheads, apart from telephone calls and electricity, are printing costs. These are paid to his brother-in-law who desktop publishes five hundred copies of the Central European Business Review four times a year. These he posts to a few selected embassies across Europe and to all the clients who have placed advertisements in the magazine. Any spares, he throws in the bin.

On paper, it’s legal.

I look Lucas directly in the eye.

‘The CEBDO is a fledgling organization that advises new businesses in central–and now eastern–Europe about the perils and pitfalls of the free market.’

He taps his jaw with the bulbous fountain pen.

‘And it’s entirely funded by private individuals? There’s no grant from the EC?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Who runs it?’

‘Nikolas Jarolmek. A Pole. His family have lived in Britain since the war.’

‘And how did you get the job?’

‘Through the Guardian. I responded to an advertisement.’

‘Against how many other candidates?’

‘I couldn’t say. I was told about a hundred and fifty.’

‘Could you describe an average day at the office?’

‘Broadly speaking, I act in an advisory capacity, either by speaking to people on the telephone and answering any questions they may have about setting up in business in the UK or by writing letters in response to written queries. I’m also responsible for editing our quarterly magazine, the Central European Business Review. That lists a number of crucial contact organizations that might prove useful to small businesses that are just starting out. It also gives details of tax arrangements in this country, language schools, that kind of thing.’

‘I see. It would be helpful if you could send me a copy.’

‘Of course.’

To explain why I am here.

The interview was set up on the recommendation of a man I barely know, a retired diplomat named Michael Hawkes. Six weeks ago I was staying at my mother’s house in Somerset for the weekend, and he came to dinner. He was, she informed me, an old university friend of my father’s.

Until that night I had never met Hawkes, had never heard my mother mention his name. She said that he had spent a lot of time with her and Dad when they were first married in the 1960s. But when the Foreign Office posted him to Moscow, the three of them had lost touch. All this was before I was born.

Hawkes retired from the Diplomatic Service earlier this year to take up a directorship at a British oil company called Abnex. I don’t know how Mum tracked down his phone number, but he showed up for dinner alone, no wife, on the stroke of eight o’clock.

There were other guests there that night, bankers and insurance brokers in bulletproof tweeds, but Hawkes was a thing apart. He had a blue silk cravat slung around his neck like a noose and a pair of velvet loafers embroidered on the toe with an elaborate coat of arms. There was nothing ostentatiously debonair about any of this, nothing vain; it just looked as if he hadn’t taken them off in twenty years. He was wearing a washed-out blue shirt with fraying collar and cuffs and stained silver cuff links that looked as though they had been in his family since the Opium Wars. In short, we got on. We sat next to each other at dinner and talked for close on three hours about everything from politics to infidelity. Three days after the party my mother told me that she had spotted Hawkes in her local supermarket, stocking up on Stolichnaya and tomato juice. Almost immediately, like a task, he asked her if I had ever thought of ‘going in for the Foreign Office.’ My mother said that she didn’t know.

‘Ask him to give me a ring if he’s interested.’

So on the telephone that night my mother did what mothers are supposed to do.

‘You remember Michael, who came to dinner?’

‘Yes,’ I said, stubbing out a cigarette.

‘He likes you. Thinks you should try out for the Foreign Office.’

‘He does?’

‘What an opportunity, Alec. To serve Queen and Country.’

I nearly laughed at this, but checked it out of respect for her old-fashioned convictions.

‘Mum,’ I said, ‘an ambassador is an honest man sent abroad to lie for the good of his country.’

She sounded impressed.

‘Who said that?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Anyway, Michael says to give him a ring if you’re interested. I’ve got the number. Fetch a pen.’

I tried to stop her. I didn’t like the idea of her putting shape on my life, but she was insistent.

‘Not everyone gets a chance like this. You’re twenty-four now. You’ve only got that small amount of money your father left you in his Paris account. It’s time you started thinking about a career and stopped working for that crooked Pole.’

I argued with her a little more, just enough to convince myself that if I went ahead it would be of my own volition and not because of some parental arrangement. Then, two days later, I rang Hawkes.

It was shortly after nine o’clock in the morning. He answered after one ring, the voice crisp and alert.

‘Michael. It’s Alec Milius.’

‘Hello.’

‘About the conversation you had with my mother.’

‘Yes.’

‘In the supermarket.’

‘You want to go ahead?’

‘If that’s possible. Yes.’

His manner was strangely abrupt. No friendly chat, no excess fat.

‘I’ll talk to one of my colleagues. They’ll be in touch.’

‘Good. Thanks.’

Three days later a letter arrived in a plain white envelope marked PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL.

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

No. 46A———Terrace

London SW1

PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL

Dear Mr Milius,

It has been suggested to me that you might be interested to have a discussion with us about fast-stream appointments in government service in the field of foreign affairs which occasionally arise in addition to those covered by the Open Competition to the Diplomatic Service. This office has a responsibility for recruitment to such appointments.

If you would like to take this possibility further, I should be grateful if you would please complete the enclosed form and return it to me. Provided that there is an appointment for which you appear potentially suitable, I shall then invite you to an exploratory conversation at this office. Your travel expenses will be refunded at the rate of a standard return rail fare plus tube fares.

I should stress that your acceptance of this invitation will not commit you in any way, nor will it affect your candidature for any government appointments for which you may apply or have applied. As this letter is personal to you, I should be grateful if you could respect its confidentiality.

Yours sincerely,

Philip Lucas

Recruitment Liaison Office

Enclosed was a standard-issue, four-page application form: name and address, education, brief employment history, and so on. I completed it within twenty-four hours–replete with lies–and sent it back to Lucas. He replied by return post, inviting me to the meeting.

I have spoken to Hawkes only once in the intervening period.

Yesterday afternoon I was becoming edgy about what the interview would entail. I wanted to find out what to expect, what to prepare, what to say. So I queued outside a Praed Street phone box for ten minutes, far enough away from the CEBDO office not to risk being seen by Nik. None of them know that I am here today.

Again Hawkes answered on the first ring. Again his manner was curt and to the point. Acting as if people were listening in on the line.

‘I feel as if I’m going into this thing with my trousers down,’ I told him. ‘I know nothing about what’s going on.’

He sniffed what may have been a laugh and replied, ‘Don’t worry about it. Everything will become clear when you get there.’

‘So there’s nothing you can tell me? Nothing I need to prepare for?’

‘Nothing at all, Alec. Just be yourself. It will all make sense later on.’

How much of this Lucas knows, I do not know. I simply give him edited highlights from the dinner and a few sketchy impressions of Hawkes’s character. Nothing permanent. Nothing of any significance.

In truth, we do not talk about him for long. The subject soon runs dry. Lucas moves on to my father and, after that, spends a quarter of an hour questioning me about my school years, dredging up the forgotten paraphernalia of my youth. He notes down all my answers, scratching away with the Mont Blanc, nodding imperceptibly at given points in the conversation.

Building a file on a man.

TWO

Official Secrets

The interview drifts on.

In response to a series of bland, straightforward questions about various aspects of my life–friendships, university, bogus summer jobs–I give a series of bland, straightforward answers designed to show myself in the correct light: as a stand-up guy, an unwavering patriot, a citizen of no stark political leanings. Just what the Foreign Office is looking for. Lucas’s interviewing technique is strangely shapeless; at no point am I properly tested by anything he asks. And he never takes the conversation to a higher level. We do not, for example, discuss the role of the Foreign Office or British policy overseas. The talk is always general, always about me.

In due course I begin to worry that my chances of recruitment are slim. Lucas has about him the air of someone doing Hawkes a favour. He will keep me in here for a couple of hours, fulfil what is required of him, and the process will go no further. Things feel over before they have really begun.

However, at around three thirty I am again offered a cup of tea. This seems significant, but the thought of it deters me. I do not have enough conversation left to last out another hour. Yet it is clear that he would like me to accept.

‘Yes, I would like one,’ I tell him. ‘Black. Nothing in it.’

‘Good,’ he says.

In this instant something visibly relaxes in Lucas, a crumpling of his suit. There is a sense of formalities passing. This impression is reinforced by his next remark, an odd, almost rhetorical question entirely out of keeping with the established rhythm of our conversation.

‘Would you like to continue with your application after this initial discussion?’

Lucas phrases this so carefully that it is like a briefly glimpsed secret, a sight of the interview’s true purpose. And yet the question does not seem to deserve an answer. What candidate, at this stage, would say no?

‘Yes, I would.’

‘In that case, I am going to go out of the room for a few moments. I will send someone in with your cup of tea.’

It is as if he has changed to a different script. Lucas looks relieved to be free of the edgy formality that has characterized the interview thus far. There is, at last, a sense of getting down to business.

From the clipboard on his lap he releases a small piece of paper, printed on both sides. This he places on the table in front of me.

‘There’s just one thing,’ he says, with well-rehearsed blandness. ‘Before I leave, I’d like you to sign the Official Secrets Act.’

The first thing I think of, even before I am properly surprised, is that Lucas actually trusts me. I have said enough here today to earn the confidence of the state. That was all it took: sixty minutes of half-truths and evasions. I stare at the document and feel suddenly catapulted into something adult, as though from this moment onward things will be expected and demanded of me. Lucas is keen to assess my reaction. Prompted by this, I lift the document and hold it in my hand like a courtroom exhibit. I am surprised by its cursoriness. It is simply a little brown sheet of paper with space at the base for a signature. I do not even bother to read the small print, because to do so might seem odd or improper. So I sign my name at the bottom of the page, scrawled and lasting. Alec Milius. The moment passes with what seems an absurd absence of seriousness, an absolute vacuum of drama. I give no thought to the consequence of it.

Almost immediately, before the ink can be properly dry, Lucas snatches the document away from me and stands to leave. Distant traffic noise on the Mall. A brief clatter in the secretarial enclave next door.

‘Do you see the file on the table?’

It has been sitting there, untouched, for the duration of the interview.

‘Yes.’

‘Please read it while I am gone. We will discuss the contents when I return.’

I look at the file, register its hard red cover, and agree.

‘Good,’ says Lucas, moving outside. ‘Good.’

Alone now in the room, I lift the file from the table as though it were a magazine in a doctor’s surgery. It is bound in cheap leather and well thumbed. I open it to the first page.

Please read the following information carefully. You are being appraised for recruitment to the Secret Intelligence Service.

I look at this sentence again, and it is only on the third reading that it begins to make any sort of sense. I cannot, in my consternation, smother a belief that Lucas has the wrong man, that the intended candidate is still sitting downstairs flicking nervously through the pages of The Times. But then, gradually, things start to take shape. There was that final instruction in Lucas’s letter: ‘As this letter is personal to you, I should be grateful if you could respect its confidentiality.’ A remark that struck me as odd at the time, though I made no more of it. And Hawkes was reluctant to tell me anything about the interview today: ‘Just be yourself, Alec. It’ll all make sense when you get there.’ Jesus. How they have reeled me in. What did Hawkes see in me in just three hours at a dinner party to convince him that I would make a suitable employee of the Secret Intelligence Service? Of MI6?

A sudden consciousness of being alone in the room checks me out of bewilderment. I feel no fear, no great apprehension, only a sure sense that I am being watched through a small panelled mirror to the left of my chair. I swivel and examine the glass. There is something false about it, something not quite aged. The frame is solid, reasonably ornate, but the glass is clean, far more so than the larger mirror in the reception area downstairs. I look away. Why else would Lucas have left the room but to gauge my response from a position next door? He is watching me through the mirror. I am certain of it.

So I turn the page, attempting to look settled and businesslike.

The text makes no mention of MI6, only of SIS, which I assume to be the same organization. This is all the information I am capable of absorbing before other thoughts begin to intrude.

It has dawned on me, a slowly revealed thing, that Michael Hawkes was a Cold War spy. That’s why he went to Moscow in the 1960s.

Did Dad know that about him?

I must look studious for Lucas. I must suggest the correct level of gravitas.

The first page is covered in information, two-line blocks of facts.

The Secret Intelligence Service (hereafter SIS), working independently from Whitehall, has responsibility for gathering foreign intelligence…

SIS officers work under diplomatic cover in British embassies overseas…

There are at least twenty pages like this one, detailing power structures within SIS, salary gradings, the need at all times for absolute secrecy. At one point, approximately halfway through the document, they have actually written: ‘Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.’

On and on it goes, too much to take in. I tell myself to keep on reading, to try to assimilate as much of it as I can. Lucas will return soon with an entirely new set of questions, probing me, establishing whether I have the potential to do this.

It’s time to move up a gear. What an opportunity, Alec. To serve Queen and Country.

The door opens, like air escaping through a seal.

‘Here’s your tea, sir.’

Not Lucas. A sad-looking, perhaps unmarried woman in late middle-age has walked into the room carrying a plain white cup and saucer. I stand up to acknowledge her, knowing that Lucas will note this display of politeness from his position behind the mirror. She hands me the tea, I thank her, and she leaves without another word.

No serving SIS officer has been killed in action since World War Two.

I turn another page, skimming the prose.

The meanness of the starting salary surprises me: only seventeen thousand pounds in the first few years, with bonuses here and there to reward good work. If I do this, it will be for love. There’s no money in spying.

Lucas walks in, no knock on the door, a soundless approach. He has a cup and saucer clutched in his hand and a renewed sense of purpose. His watchfulness has, if anything, intensified. Perhaps he hasn’t been observing me at all. Perhaps this is his first sight of the young man whose life he has just changed.

He sits down, tea on the table, right leg folded over left. There is no ice-breaking remark. He dives straight in.

‘What are your thoughts about what you’ve been reading?’

The weak bleat of an internal phone sounds on the other side of the door, stopping efficiently. Lucas waits for my response, but it does not come. My head is suddenly loud with noise and I am rendered incapable of speech. His gaze intensifies. He will not speak until I have done so. Say something, Alec. Don’t blow it now. His mouth is melting into what I perceive as a disappointment close to pity. I struggle for something coherent, some sequence of words that will do justice to the very seriousness of what I am now embarked upon, but the words simply do not come. Lucas appears to be several feet closer now than he was before, and yet his chair has not moved an inch. How could this have happened? In an effort to regain control of myself, I try to remain absolutely still, to make our body language as much of a mirror as possible: arms relaxed, legs crossed, head upright and looking ahead. In time–what seem vast, vanished seconds–the beginning of a sentence forms in my mind, just the faintest of signals. And when Lucas makes to say something, as if to end my embarrassment, it acts as a spur.

I say, ‘Well…now that I know…I can understand why Mr Hawkes didn’t want to say exactly what I was coming here to do today.’

‘Yes.’

The shortest, meanest, quietest yes I have ever heard.

‘I found the pamphl–the file very interesting. It was a surprise.’

‘Why is that exactly? What surprised you about it?’

‘I thought, obviously, that I was coming here today to be interviewed for the Diplomatic Service, not for SIS.’

‘Of course,’ he says, reaching for his tea.

And then, to my relief, he begins a long and practiced monologue about the work of the Secret Intelligence Service, an eloquent, spare r?sum? of its goals and character. This lasts as long as a quarter of an hour, allowing me the chance to get myself together, to think more clearly and focus on the task ahead. Still spinning from the embarrassment of having frozen openly in front of him, I find it difficult to concentrate on Lucas’s voice. His description of the work of an SIS officer appears to be disappointingly void of macho derring-do. He paints a lustreless portrait of a man engaged in the simple act of gathering intelligence, doing so by the successful recruitment of foreigners sympathetic to the British cause who are prepared to pass on secrets for reasons of conscience or financial gain. That, in essence, is all that a spy does. As Lucas tells it, the more traditional aspects of espionage–burglary, phone tapping, honey traps, bugging–are a fiction. It’s mostly desk work. Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.

‘Clearly, one of the more unique aspects of SIS is the demand for absolute secrecy,’ he says, his voice falling away. ‘How would you feel about not being able to tell anybody what you do for a living?’

I guess that this is how it would be. Nobody, not even Kate, knowing any longer who I really was. A life of absolute anonymity.

‘I wouldn’t have any problem with that.’

Lucas begins to take notes again. That was the answer he was looking for.

‘And it doesn’t concern you that you won’t receive any public acclaim for the work you do?’

He says this in a tone that suggests that it bothers him a great deal.

‘I’m not interested in acclaim.’

A seriousness has enveloped me, nudging panic aside. An idea of the job is slowly composing itself in my imagination, something that is at once very straightforward but ultimately obscure. Something clandestine and yet moral and necessary.

Lucas ponders the clipboard in his lap.

‘You must have some questions you want to ask me.’

‘Yes,’ I tell him. ‘Would members of my family be allowed to know that I am an SIS officer?’

Lucas appears to have a checklist of questions on his clipboard, all of which he expects me to ask. That was obviously one of them, because he again marks the page in front of him with his snub-nosed fountain pen.

‘Obviously, the fewer people that know, the better. That usually means wives.’

‘Children?’

‘No.’

‘But obviously not friends or other relatives?’

‘Absolutely not. If you are successful after Sisby, and the panel decides to recommend you for employment, then we would have a conversation with your mother to let her know the situation.’

‘What is Sisby?’

‘The Civil Service Selection Board. Sisby, as we call it. If you are successful at this first interview stage, you will go on to do Sisby in due course. This involves two intensive days of intelligence tests, interviews, and written papers at a location in Whitehall, allowing us to establish if you are of a high enough intellectual standard for recruitment to SIS.’

The door opens without a knock and the same woman who brought in my tea, now cold and untouched on the table, walks in. She smiles apologetically in my direction, with a flushed, nervous glance at Lucas. He looks visibly annoyed.

‘I do apologize, sir.’ She is frightened of him. ‘This just came through for you, and I felt you should see it right away.’

She hands him a single sheet of fax paper. Lucas looks over at me quickly and proceeds to read it.

‘Thank you.’ The woman leaves and he turns to me. ‘I have a suggestion. If you have no further questions, I think we should finish here. Will that be all right?’

‘Of course.’

There was something on the fax that necessitated this.

‘You will obviously have to think things over. There are a lot of issues to consider when deciding to become an SIS officer. So let’s end this discussion now. I will be in touch with you by post in the next few days. We will let you know at that stage if we want to proceed with your application.’

‘And if you do?’

‘Then you will be invited back here for a second interview with one of my colleagues.’

As he stands up to leave, Lucas folds the piece of paper in two and slips it into the inside pocket of his jacket. Leaving the recruitment file on the table, he gestures with an extended right arm toward the door, which has been left ajar by the secretary. I walk out ahead of him and immediately begin to feel all the stiffness of formality falling away from me. It is a relief to leave the room.

The girl in the neat red suit is standing outside waiting, somehow prettier than she was at two o’clock. She looks at me, gauges my mood, and then sends out a warm broad smile that is full of friendship and understanding. She knows what I’ve just been through. I feel like asking her out for dinner.

‘Ruth, will you show Mr Milius to the door? I have some business to attend to.’

Lucas has barely emerged from his office: he is lingering in the doorway behind me, itching to get back inside.

‘Of course,’ she says.

So our separation is abrupt. A last glance into each other’s eyes, a grappled shake of the hand, a reiteration that he will be in touch. And then Philip Lucas vanishes back into his office, firmly closing the door.

THREE

Tuesday, 4 July

At dawn, five days later, my first waking thought is of Kate, as though someone trips a switch behind my closed eyes and she blinks into the morning. It has been like this, on and off, for four months now. Sometimes, still caught in a half dream, I will reach for her as though she were actually beside me in bed. I try to smell her, try to gauge the pressure and softness of her kisses, the delicious sculpture of her spine. Then we lie together, whispering quietly, kissing. Just like old times.

Drawing the curtains, I see that the sky is white, a cloudy midsummer morning that will burn off at noon and break into a good blue day.

All that I have wanted is to tell Kate about SIS. At last something has gone right for me, something that she might be proud of. Someone has given me the chance to put my life together, to do something constructive with all these mind wanderings and ambition. Wasn’t that what she always wanted? Wasn’t she always complaining about how I wasted opportunities, how I was always waiting for something better to come along? Well, this is it.

But I know that it will not be possible. I have to let her go. Finding it so difficult to let her go.

I shower, dress, and take the tube to Edgware Road, but I am not the first at work. Coming down the narrow, sheltered mews, I see Anna up ahead, fighting vigorously with the lock on the garage door. A heavy bunch of keys drops from her right hand. She stands up to straighten her back and sees me in the distance, her expression one of unambiguous contempt. Not so much as a nod. I push a splay-fingered hand through my hair and say good morning.

‘Hello,’ she says archly, twisting the key in the lock.

She’s growing her hair. Long brown strands flecked with old highlights and trapped light.

‘Why the fuck doesn’t Nik give me a key that fucking works?’

‘Try mine.’

I steer my key in toward the garage door, a movement that causes Anna to pull her hand out of the way like a flick knife. Her keys fall onto the grey step and she says fuck again. Simultaneously, her bicycle, which has been resting against the wall beside us, topples to the ground. She walks over to pick it up as I unlock the door and go inside.

The air is wooden and musty. Anna comes through the door behind me with a squeezed smile. She is wearing a summer dress of pastel blue cotton dotted with pale yellow flowers. A thin layer of sweat glows on the freckled skin above her breasts, soft as moons. With my index finger I flick the switches one by one. The strip lights in the small office strobe.

There are five desks inside, all hooked up to phones. I weave through them to the far side of the garage, turning right into the kitchen. The kettle is already full and I press it, lifting two mugs from the drying rack. The toilet perches in the corner of the narrow room, topped by rolls of pink paper. Someone has left a half-finished cigarette on the tank that has stained the ceramic. The kettle’s scaly deposits crackle faintly as I open the door of the fridge.

Fresh milk? No.

When I come out of the kitchen Anna is already on the phone, talking softly to someone in the voice that she uses for boys. Perhaps she left him slumbering in her wide, low bed this morning, the smell of her sex on the pillow. She has opened up the wooden doors of the garage so that daylight has filled the room. I hear the kettle click. Anna catches me looking at her and swivels her chair so that she is facing out onto the mews. I light a cigarette, my last one, and wonder who he is.

‘So,’ she says to him, her voice a naughty grin, ‘what are you going to do today?’ A pause. ‘Oh, Bill, you’re so lazy…’

She likes his being lazy, she approves of it.

‘Okay, that sounds good. Mmmm. I’ll be finished here at six, maybe earlier if Nik lets me go.’

She turns and sees that I am still watching her.

‘Just Alec. Yeah. Yeah. That’s right.’

Her voice drops as she says this. He knows all about what happened between us. She must have told him everything.

‘Well, they’ll be here in a minute. Okay. See you later. Bye.’

She turns back into the room and hangs up the phone.

‘New boyfriend?’

‘Sorry?’ Standing up, she passes me on her way into the kitchen. I hear her open the door of the fridge, the minute electric buzz of its bright white light, the soft plastic suck of its closing.

‘Nothing,’ I say, raising my voice so that she can hear me. ‘I just said, is that your new boyfriend?’

‘No, it was yours,’ she says, coming out again. ‘I’m going to buy some milk.’

As she leaves, a telephone rings in the unhoovered office, but I let the answering machine pick it up. Anna’s footsteps clip away along the cobbles and a car starts up in the mews. I step outside.

Des, the next-door neighbour, is buckled into his magnesium E-type Jag, revving the engine. Des always wears loose black suits and shirts with a sheen, his long silver hair tied back in a ponytail. None of us has ever been able to work out what Des does for a living. He could be an architect, a film producer, the owner of a chain of restaurants. It’s impossible to tell just by looking into the windows of his house, which reveal expensive sofas, a wide-screen television, plenty of computer hardware, and, right at the back of the sleek white kitchen, an industrial-size espresso machine. On the rare occasions when Des speaks to anyone in the CEBDO office, it is to complain about excessive noise or car-parking violations. Otherwise, he is an unknown quantity.

Nik shuffles his shabby walk down the mews just as Des is sliding out of it in his low-slung, antique fuck machine. I go back inside and look busy. Nik comes through the open door and glances up at me, still moving forward. He is a small man.

‘Morning, Alec. How are we today? Ready for a hard day’s work?’

‘Morning, Nik.’

He swings his briefcase up onto his desk and wraps his old leather jacket around the back of the chair.

‘Do you have a cup of coffee for me?’

Nik is a bully and, like all bullies, sees everything in terms of power. Who is threatening me; whom can I threaten? To suffocate the constant nag of his insecurity he must make others feel uncomfortable. I say, ‘Funnily enough, I don’t. The batteries are low on my ESP this morning, and I didn’t know exactly when you’d be arriving.’

‘You being funny with me today, Alec? You feeling confident or something?’

He doesn’t look at me while he says this. He just shuffles things on his desk.

‘I’ll get you a coffee, Nik.’

‘Thank you.’

So I find myself back in the kitchen, reboiling the kettle. And it is only when I am crouched on the floor, peering into the fridge, that I remember Anna has gone out to buy milk. On the middle shelf, a hardened chunk of overly yellow butter wrapped in torn gold foil is slowly being scarfed by mould.

‘We don’t have any milk,’ I call out. ‘Anna’s gone out to get some.’

There’s no answer, of course.

I put my head around the door of the kitchen and say to Nik, ‘I said there’s no milk. Anna’s gone–‘

‘I hear you. I hear you. Don’t be panicking about it.’

I ache to tell him about SIS, to see the look on his cheap, corrupted face. Hey, Nik, you’re twice my age and this is all you’ve been able to come up with: a low-rent, dry-rot garage in Paddington, flogging lies and phony advertising space to your own countrymen. That’s the extent of your life’s work. A few phones, a fax machine, and three secondhand computers running on outdated software. That’s what you have to show for yourself. That’s all you are. I’m twenty-four, and I’m being recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service.

It is five o’clock in the afternoon in Brno, one hour ahead of London. I am talking to a Mr Klemke, the managing director of a firm of building contractors with ambitions to move into western Europe.

‘Particularly France,’ he says.

‘Well, then I think our publication would be perfect for you, sir.’

‘Publicsation? I’m sorry. This word.’

‘Our publication, our magazine. The Central European Business Review. It’s published every three months and has a circulation of four hundred thousand copies worldwide.’

‘Yes, yes. And this is new magazine, printed in London?’

Anna, back from a long lunch, sticks a Post-it note on the desk in front of me. Scrawled in girly swirls she has written, ‘Saul rang. Coming here later.’

‘That’s correct,’ I tell Klemke. ‘Printed here in London and distributed worldwide. Four hundred thousand copies.’

Nik is looking at me.

‘And, Mr Mills, who is the publisher of this magazine? Is it yourself?’

‘No, sir. I am one of our advertising executives.’

‘I see.’

I envision him as large and rotund, a benign Robert Maxwell. I envision them all as benign Robert Maxwells.

‘And you want me to advertise, is that what you are asking?’

‘I think it would be in your interest, particularly if you are looking to expand into western Europe.’

‘Yes, particularly France.’

‘France.’

‘And you have still not told me who is publishing this magazine in London. The name of person who is editor.’

Nik has started reading the sports pages of The Independent.

‘It’s a Mr Jarolmek.’

He folds one side of the newspaper down with a sudden crisp rattle, alarmed.

Silence in Brno.

‘Can you say this name again, please?’

‘Jarolmek.’

I look directly at Nik, eyebrows raised, and spell out J-a-r-o-l-m-e-k with great slowness and clarity down the phone. Klemke may yet bite.

‘I know this man.’

‘Oh, you do?’

Trouble.

‘Yes. My brother, of my wife, he is a businessman also. In the past he has published with this Mr Jarolmek.’

‘In the Central European Business Review?’

‘If this is what you are calling this now.’

‘It’s always been called that.’

Nik puts down the paper, pushes his chair out behind him, and stands up. He walks over to my desk and perches on it. Watching me. And there, on the other side of the mews, is Saul, leaning coolly against the wall smoking a cigarette like a private investigator. I have no idea how long he has been standing there. Something heavy falls over in Klemke’s office.

‘Well, it’s a small world,’ I say, gesturing to Saul to come in. Anna is grinning as she dials a number on her telephone. Long brown slender arms.

‘It is my belief that Jarolmek is a robber and a con man.’

‘I’m sorry, uh, I’m sorry, why…why do you feel that?’

A quizzical look from Nik, perched there. Saul now coming in through the door.

‘My brother paid a large sum of money to your organization two separate times–‘

Don’t let him finish.

‘–And he didn’t receive a copy of the magazine? Or experience any feedback from his advertisement?’

‘Mr Mills, do not interrupt me. I have something I want to say to you and I do not wish to be interrupted.’

‘I’m sorry. Do go on.’

‘Yes, I will go on. I will go on. My brother then met with a British diplomat in Prague at a function dinner who had not heard of your publication.’

‘Really?’

‘And when he goes to look it up, it is not listed in any of our documentation here in Czech Republic. How do you explain this?’

‘There must be some misunderstanding.’

Nik stands up and spits, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ in an audible whisper. He presses the loudspeaker button on my telephone and Klemke’s riled gravelly voice echoes out into the room.

‘Misunderstanding? No, I don’t believe it is. You are a fraud. My brother of my wife has made inquiries into your circulation and it appears that you do not sell as widely as you say. You are lying to people in Europe and making promises. My brother was going to report you. And now I will do the same.’

Nik stabs the button again and pulls the receiver out of my hand.

‘Hello. Yes. This is Nikolas Jarolmek. Can I help you with something?’

Saul looks at me quizzically, nodding his head at Nik, fishing lazily about in the debris on my desk. He has had his hair cut very short, almost shaved to the skull.

Suddenly Nik is shouting, a clatter of a language I do not understand. Cursing, sweating, chopping the air with his small stubby hands. He spits insults into the phone, parries Klemke’s threats with raging animosities, hangs up with a bang.

‘You stupid fucking arsehole!’

He turns on me, shouting, his arms spread like push-ups on the desk.

‘What were you doing keeping that fucker on the phone? You could get me in jail. You stupid fucking…cunt!’

Cunt sounds like a word he has just learned in the playground.

‘What, for fuck’s sake? What the fuck was I supposed to do?’

‘What were you…you stupid. Fucking hell, I should pay my dog to sit there. My fucking dog would do a better job than you.’

I am too ashamed to look at Saul.

‘Nik, I’m sorry, but–‘

‘Sorry? Oh, well then, that’s all right…’

‘No, sorry, but–‘

‘I don’t care if you’re sorry.’

‘Look!’

This from Saul. He is on his feet. He’s going to say something. Oh, Jesus.

‘He’s not saying he’s sorry. If you’d just listen, he’s not saying he’s sorry. It’s not his fault if some wanker in Warsaw catches on to what you’re up to and starts giving him an earful! Why don’t you calm down, for Christ’s sake?’

‘Who the fuck are you?’ says Nik. He really likes this guy.

‘I’m a friend of Alec’s. Take it easy.’

‘And he can’t take care of himself? You can’t take care of yourself now, Alec, eh?’

‘Of course he can take care of himself…’

‘Nik, I can take care of myself. Saul, it’s all right. We’ll go and get a coffee. I’ll just get out of here for a while.’

‘For more than a while,’ says Nik. ‘Don’t come back. I don’t want to see you. You come back tomorrow. This is enough for one day.’

‘Jesus, what a cunt.’

Now Saul is someone who really knows the time and place for effective use of the word cunt. I feel like asking him to say it again.

‘I can’t believe you work for that guy.’

We are standing on either side of a table football game in a caf? on Edgware Road. I take a worn white ball from the trough below my waist and feed it through the hole onto the table. Saul traps the ball with the still black feet of his plastic man before gunning it down the table into my goal.

‘The object of the game is to stop that kind of thing from happening.’

‘It’s my goalkeeper.’

‘What’s wrong with him?’

‘He has personal problems.’

Saul gives a wheezy laugh, lifts his cigarette from a Coca-Cola ashtray, and takes a drag.

‘What language was it that Nik was speaking?’

‘Czech. Slovak. One of the two.’

‘Play, play.’

The ball thunders and slaps on the rocking table.

‘Better than Nintendo, eh?’

‘Yes, Grandpa,’ says Saul, scoring.

‘Shit.’

He slides another red counter along the abacus. Five–nil.

‘Don’t be afraid to compete, Alec. Carpe diem.’

I attempt a deft sideways shunt of the ball in midfield, but it skewers away at an angle. Coming back down the table, Saul saying, ‘Now that is skill,’ it rolls loose in front of my centre half. I grip the clammy handle with rigid fingers and whip it so that the neat row of figures rotates in a propeller blur. Saul’s hand flies to the right and his goalkeeper saves the incoming ball.

‘That’s illegal,’ he says. The shorter haircut suits him.

‘I’m competing.’

‘Oh, right.’

Six–nil.

‘How did that happen?’

‘Because you’re very bad at this game. Listen, I’m sorry if I interfered back there…’

‘No.’

‘What?’

‘It’s okay.’

‘No, I mean it. I’m sorry.’

‘I know you are.’

‘I probably shouldn’t have stuck my foot in.’

‘No, you probably shouldn’t have stuck your foot in. But that’s how you are. I’d rather you spoke your mind and stood up for your friends than bit your tongue for the sake of decorum. I understand. You don’t have to explain. I don’t care about the job, so it’s okay.’

‘Okay.’

We tuck the subject away like a letter.

‘So what are you doing up here?’

‘I just thought I’d come up and see you. I’ve been busy with work, haven’t seen you for a week or so. You free tonight?’

‘Yeah.’

‘We can go back to mine and eat.’

‘Good.’

Saul is the only person in whom I have considered confiding, but now that we are face-to-face it does not seem necessary to tell him about SIS. My reluctance has nothing to do with official secrecy: if I asked him to, Saul would keep his mouth shut for thirty years. Trust is not an element in the decision.

There has always been something quietly competitive about our friendship–a rivalry of intellects, a need to kiss the prettier girl. Adolescent stuff. Nowadays, with school just a vague memory, this competitiveness manifests in an unspoken system of checks and balances on each other’s lives: who earns more money, who drives the faster car, who has laid the more promising path into the future. This rivalry, which is never articulated but constantly acknowledged by both of us, is what prevents me from talking to Saul about what is now the most important and significant aspect of my life. I cannot confide in him when the indignity of rejection by SIS is still possible. It is, perversely, more important to me to save face with him than to seek his advice and guidance.

I take out the last ball.

We eat stir-fry chicken side by side off a low table in the larger of the two sitting rooms in Saul’s flat, hunched forward on the sofa, sweating under the chilli.

‘So is your boss always like that?’

It takes me a moment to realize that Saul is talking about the argument with Nik this afternoon.

‘Forget about it. He was just taking advantage of the fact that you were there to ridicule me in front of the others. He’s a bully. He gets a kick out of scoring points off people. I couldn’t give a shit.’

‘Right.’

Small black-and-white marble squares are sunk into the top of the table, forming a chessboard, which is chipped and stained after years of use.

‘How long have you been there now?’

‘With Nik? About a year.’

‘And you’re going to stay on? I mean, where’s it going?’

I don’t like talking about this with Saul. His career, as a freelance assistant director, is going well, and there’s something hidden in his questions, a glimpse of disappointment.

‘What d’you mean, where’s it going?’

‘Just that. I didn’t think you’d stay there as long as you have.’

‘You think I ought to have a more serious job? Something with a career graph, a ladder of promotion?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘You sound like a teacher.’

We are silent for a while. Staring at walls.

‘I’m applying to join the Foreign Office.’

This just comes out. I didn’t plan it.

‘You’re what?’

‘Seriously.’ I turn to look at him. ‘I’ve filled in the application forms and done some preliminary IQ tests. I’m waiting to hear back from them.’

The lie falls in me like a dropped stitch.

‘Christ. When did you decide this?’

‘About two months ago. I just had a bout of feeling unstretched, needed to take some action and sort my life out.’

‘What, so you want to be a diplomat?’

‘Yeah.’

It doesn’t feel exactly wrong to be telling him this. At some point in the next eighteen months, a time will come when I may be sent overseas on a posting to a foreign embassy. Saul’s knowing now of my intention to join the Diplomatic Service will help allay any suspicions he might have in the future.

‘I’m surprised,’ he says, on the brink of being opinionated. ‘You sure you know what you’re letting yourself in for?’

‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning, why would you want to join the Foreign Office?’

A little piece of spring onion flies out of his mouth.

‘I’ve already told you. Because I’m sick of working for Nik. Because I need a change.’

‘You need a change.’

‘Yes.’

‘So why become a civil servant? That’s not you. Why join the Foreign Office? Fifty-seven old farts pretending that Britain still has a role to play on the world stage. Why would you want to become a part of something that’s so obviously in decline? All you’ll do is stamp passports and attend business delegations. The most fun a diplomat ever has is bailing some British drug smuggler out of prison. You could end up in Albania, for fuck’s sake.’

We are locked into the absurdity of arguing about a problem that does not exist.

‘Or Washington.’

‘In your dreams.’

‘Well, thanks for your support.’

It is still light outside. Saul puts down his fork and twists around. A flicker of eye contact, and then he looks away, the top row of his teeth pressing down on a reddened bottom lip.

‘Look. Whatever. You’d be good at it.’

He doesn’t believe that for a second.

‘You don’t believe that for a second.’

‘No, I do.’ He plays with his unfinished food, looking at me again. ‘Have you thought about what it would be like to live abroad? I mean, is that what you really want?’

For the first time it strikes me that I may have confused the notion of serving the state with a longstanding desire to run away from London, from Kate, and from CEBDO. This makes me feel foolish. I am suddenly drunk on weak American beer.

‘Saul, all I want to do is put something back in. Living abroad or living here, it doesn’t matter. And the Foreign Office is one way of doing that.’

‘Put something back into what?’

‘The country.’

‘What is that? You don’t owe anyone. Who do you owe? The queen? The empire? The Conservative Party?’

‘Now you’re just being glib.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m serious. The only people you owe are your friends and your family. That’s it. Loyalty to the Crown, improving Britain’s image abroad, whatever bullshit they try to feed you, that’s an illusion. I don’t want to be rude, but your idea of putting something back into society is just vanity. You’ve always wanted people to rate you.’

Saul watches carefully for my reaction. What he has just said is actually fairly offensive. I say, ‘I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wanting people to have a good opinion of you. Why not strive to be the best you can? Just because you’ve always been a cynic doesn’t mean that the rest of us can’t go about trying to improve things.’

‘Improve things?’ He looks astonished. Neither of us is in the least bit angry.

‘Yes. Improve things.’

‘That’s not you, Alec. You’re not a charity worker.’

‘Don’t you think we’ve been spoiled as a generation? Don’t you think we’ve grown used to the idea of take, take, take?’

‘Not really. I work hard for a living. I don’t go around feeling guilty about that.’

I want to get this theme going, not least because I don’t in all honesty know exactly how I feel about it.

‘Well, I really believe we have,’ I say, taking out a cigarette, offering one to Saul. ‘And that’s not because of vanity or guilt or delusion.’

‘Believe what?’

‘That because none of us have had to struggle or fight for things in our generation we’ve become incredibly indolent and selfish.’

‘Where’s this coming from? I’ve never heard you talk like this in your life. What happened, did you see some documentary about the First World War and feel guilty that you didn’t do more to suppress the Hun?’

‘Saul…’

‘Is that it? Do you think we should start a war with someone, prune the vine a bit, just to make you feel better about living in a free country?’

‘Come on. You know I don’t think that.’

‘So–what? Is it morality that makes you want to join the Foreign Office?’

‘Look. I don’t necessarily think that I’m going to be able to change anything in particular. I just want to do something that feels…significant.’

‘What do you mean “significant”?’

Despite the fact that our conversation has been premised on a lie, there are nevertheless issues emerging here about which I feel strongly. I stand up and walk around, as if being upright will lend some shape to my words.

‘You know–something worthwhile, something meaningful, something constructive. I’m sick of just surviving, of all the money I earn being plowed back into rent and bills and taxes. It’s okay for you. You don’t have to pay anything on this place. At least you’ve met your landlord.’

‘You’ve never met your landlord?’

‘No.’ I am gesticulating like a TV preacher. ‘Every month I write a cheque for four hundred and eighty quid to a Mr J. Sarkar–I don’t even know his first name. He owns an entire block in Uxbridge Road: flats, shops, taxi ranks, you name it. It’s not like he needs the money. Every penny I earn seems to go toward making sure that somebody else is more comfortable than I am.’

Saul extinguishes his cigarette in a pile of cold noodles. He looks suddenly awkward. Money talk always brings that out in him. Rich guilt.

‘I’ve got the answer,’ he says, trying to lift himself out of it. ‘You need to get yourself an ideology, Alec. You’ve got nothing to believe in.’

‘What do you suggest? Maybe I should become a born-again Christian, start playing guitar at Holy Trinity Brompton and holding prayer meetings.’

‘Why not? We could say grace whenever you come round for dinner. You’d get a tremendous kick out of feeling superior to everyone.’

‘At university I always wanted to be one of those guys selling Living Marxist. Imagine having that much faith.’

‘It’s a little pass?,’ Saul says. ‘And cold during the winter months.’

I pour the last dregs of my beer into a glass and take a swig that is sour and dry. On the muted television screen the Nine o’Clock News is beginning. We both look up to see the headlines. Then Saul switches it off.

‘Game of chess?’

‘Sure.’

We play the opening moves swiftly, the thunk of the pieces falling regularly on the strong wooden surface. I love that sound. There are no early captures, no immediate attacks. We exchange bishops, castle king-side, push pawns. Neither one of us is prepared to do anything risky. Saul keeps up an impression of easy joviality, making gags and farting away the stir-fry, but I know that, like me, he is concealing a deep desire to win.

After twenty-odd moves, the game is choking up. If Saul wants it, there’s the possibility of a three-piece swap in the centre of the board that will reap two pawns and a knight each, but it isn’t clear who will be left with the advantage if the exchange takes place. Saul ponders things, staring intently at the board, occasionally taking a gulp of wine. To hurry him along I say, ‘Is it my go?’ and he says, ‘No. Me. Sorry, taking a long time.’ Then he thinks for another three or four minutes. My guess is he’ll shift his rook into the centre of the back rank, freeing it to move down the middle.

‘I’m going for a piss.’

‘Make your move first.’

‘I’ll do it when I come back,’ he sighs, standing up and making his way down the hall.

What I do next is achieved almost without thinking. I listen for the sound of the bathroom door closing, then quickly advance the pawn on the f-file a single space. I retract my right hand and study the difference in the shape of the game. The pawn is protected there by a knight and another pawn, and it will, in three or four moves’ time, provide a two-pronged defence when I slide in to attack Saul’s king. It’s a simple, minute adjustment to the game that should go unnoticed in the thick gathering of pieces fighting for control of the centre.

When he returns from the bathroom, Saul’s eyes seem to fix immediately on the cheating pawn. He may have spotted it. His forehead wrinkles and he chews the knuckle on his index finger, trying to establish what has changed. But he says nothing. Within a few moments he has made his move–the rook to the centre of the back rank–and sat back deep into the sofa. Play continues nervously. I develop king-side, looking to use the advanced pawn as cover for an attack. Then Saul, as frustrated as I am, offers a queen swap after half an hour of play. I accept, and from there it’s a formality. With the pawn in such an advanced position, my formation is marginally stronger; it’s just a matter of wearing him down. Saul parries a couple of attacks, but the sheer weight of numbers begins to tell. He resigns at twenty to eleven.

‘Nice going,’ he says, offering me a sweaty palm.

We always shake hands afterwards.

At 1:00 A.M., drunk and tired, I sit slumped on the backseat of an unlicensed minicab, going home to Shepherd’s Bush.

There is a plain white envelope on my doormat, second post, marked PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL.

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

No. 46A———Terrace

London SW1

PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL

Dear Mr Milius,

Following your recent conversation with my colleague, Philip Lucas, I should like to invite you to attend a second interview on Tuesday, July 25th, at 10 o’clock.

Please let me know if this date will be convenient for you.

Yours sincerely,

Patrick Liddiard

Recruitment Liaison Office

FOUR

Positive Vetting

The second interview passes like a foregone conclusion.

This time around I am treated with deference and respect by the cop on the door, and Ruth greets me at the bottom of the staircase with the cheery familiarity of an old friend.

‘Good to see you again, Mr Milius. You can go straight up.’

Throughout the morning there is a pervading sense of acceptance, a feeling of gradual admission to an exclusive club. My first encounter with Lucas was clearly a success. Everything about my performance that day has impressed them.

In the secretarial enclave, Ruth introduces me to Patrick Liddiard, who exudes the clean charm and military dignity of the typical Foreign Office man. This is the face that built the empire: slim, alert, colonizing. He is impeccably turned out in gleaming brogues and a wife-ironed shirt that is tailored and crisp. His suit, too, is evidently custom-made, a rich grey flannel cut lean against his slender frame. He looks tremendously pleased to see me, pumping my hand with vigour, cementing an immediate connection between us.

‘Very nice to meet you,’ he says. ‘Very nice indeed.’

His voice is gentle, refined, faintly plummy, exactly as his appearance suggested it would be. Not a wrong note. There is a warmth suddenly about all this, a clubbable ease entirely absent on my previous visit.

The interview itself does nothing to dispel this impression. Liddiard appears to treat it as a mere formality, something to be gone through before the rigours of Sisby. That, he tells me, will be a test of mettle, a tough two-day candidate analysis comprising IQ tests, essays, interviews, and group discussions. He makes it clear to me that he has every confidence in my ability to succeed at Sisby and to go on to become a successful SIS officer.

There is only one conversational exchange between us that I consider especially significant. It comes just as the first hour of the interview is drawing to a close.

We have finished discussing the European monetary union–issues of sovereignty and so on–when Liddiard makes a minute adjustment to his tie, glances down at the clipboard in his lap, and asks me, very straightforwardly, how I would feel about manipulating people for a living.

Initially I am surprised that such a question could emerge from the apparently decent, old-fashioned gent sitting opposite me. Liddiard has been so courteous, so civilized up to this point, that to hear talk of deception from him is jarring. As a result, our conversation turns suddenly watchful, and I have to check myself out of complacency. We have arrived at what feels like the nub of the thing, the rich centre of the clandestine life.

I repeat the question, buying myself some time.

‘How would I feel about manipulating people?’

‘Yes,’ he says, with more care in his voice than he has allowed so far.

I must, in my answer, strike a delicate balance between the appearance of moral rectitude and the implied suggestion that I am capable of pernicious deceits. It is no good telling him outright of my preparedness to lie, although that is the business he is in. On the contrary, Liddiard will want to know that my will to do so is born of a deeper dedication, a profound belief in the ethical legitimacy of SIS. He is clearly a man possessed of values and moral probity: like Lucas, he sees the work of the Secret Intelligence Service as a force for good. Any suggestion that the intelligence services are involved in something fundamentally corrupt would appall him.

So I pick my words with care.

‘If you are searching for someone who is genetically manipulative, then you’ve got the wrong man. Deceit does not come easily to me. But if you are looking for somebody who would be prepared to lie when and if the circumstances demanded it, then that would be something I would be capable of doing.’

Liddiard allows an unquiet silence to linger in the room. And then he suddenly smiles, warmly, so that his teeth catch a splash of light. I have said the right thing.

‘Good,’ he says, nodding. ‘Good. And what about being unable to tell your friends about what you do? Have you had any concerns about that? We obviously prefer it that you keep the number of people who know about your activities to an absolute minimum. Some candidates have a problem with that.’

‘Not me. Mr Lucas told me in my previous interview that officers are allowed to tell their parents.’

‘Yes.’

‘But as far as friends are concerned…’

‘Of course not.’

‘That’s what I’d come to understand.’

Both of us nod simultaneously. Suddenly, however, for no better reason than that I want to appear solid and reliable, I do something quite unexpected. It is unplanned and dumb. A needless lie to Liddiard that could prove costly.

‘It’s just that I have a girlfriend.’

‘I see. And have you told her about us?’

‘No. She knows that I’m here today, but she thinks I’m applying for the Diplomatic Service.’

‘Is this a serious relationship?’

‘Yes. We’ve been together for almost five years. It’s very probable that we’ll get married. So she should know about this, to see if she’s comfortable with it.’

Liddiard touches his tie again.

‘Of course,’ he says. ‘What is the girl’s name?’

‘Kate. Kate Allardyce.’

Liddiard writes down Kate’s name in his notes. Why am I doing this? They won’t care that I am about to get married. They won’t think any more of me for being able to sustain a long-term relationship. If anything, they would prefer me to be alone.

He asks when she was born.

‘December twenty-eighth, 1971.’

‘Where?’

‘Argentina.’

A tiny crease saunters across his forehead.

‘And what is her current address?’

I had no idea that he would ask so much about her. I give the address where we used to live together.

‘Will you want to interview her? Is that why you want all this information?’

‘No, no,’ he says quickly. ‘It’s purely for vetting purposes. There shouldn’t be a problem. But I must ask you to refrain from discussing your candidature with her until after the Sisby examinations.’

‘Of course.’

Then, as a savoured afterthought, he adds, ‘Sometimes wives can make a substantial contribution to the work of an SIS officer.’

FIVE

Day One/Morning

It’s 6:00 A.M. on Wednesday, August 9. There are two and a half hours until Sisby.

I have laid out a grey flannel suit on my bed and checked it for stains. Inside the jacket there’s a powder-blue shirt at which I throw ties, hoping for a match. Yellow with faint white dots. Pistachio green shot through with blue. A busy paisley, a sober navy one-tone. Christ, I have awful ties. Outside, the weather is overcast and bloodless. A good day to be indoors.

After a bath and a stinging shave I settle down in the sitting room with a cup of coffee and some back issues of The Economist, absorbing its opinions, making them mine. According to the Sisby literature given to me by Liddiard at the end of our interview in July, ‘all SIS candidates will be expected to demonstrate an interest in current affairs and a level of expertise in at least three or four specialist subjects.’ That’s all I can prepare for.

I am halfway through a profile of Gerry Adams when the faint moans of my neighbours’ early-morning lovemaking start to seep through the floor. In time there is a faint groan, what sounds like a cough, then the thud of wood on wall. I have never been able to decide whether she is faking it. Saul was over here once when they started up and I asked his opinion. He listened for a while, ear close to the floor, and made the solid point that you can only hear her and not him, an imbalance that suggests female overcompensation. ‘I think she wants to enjoy it,’ he said, thoughtfully, ‘but something is preventing that.’

I put the dishwasher on to smother the noise, but even above the throb and rumble I can still hear her tight, sobbing emissions of lust. Gradually, too rhythmically, she builds to a moan-filled climax. Then I am left in the silence with my mounting anxiety.

Time is passing. It frustrates me that I can do so little to prepare for the next two days. The Sisby programme is a test of wits, of quick thinking and mental panache. You can’t prepare for it, like an exam. It’s survival of the fittest.

Grab your jacket and go.

The Sisby examination centre is at the north end of Whitehall. This is the part of town they put in movies as an establishing shot to let audiences in South Dakota know that the action has moved to London: a wide-angle view of Nelson’s Column, with a couple of double-decker buses and taxis queuing up outside the broad, serious flank of the National Gallery. Then cut to Harrison Ford in his suite at The Grosvenor.

The building is a great slab of nineteenth-century brown brick. People are already starting to go inside. There is a balding man in a grey uniform behind a reception desk enjoying a brief flirtation with power. He looks shopworn, overweight, and inexplicably pleased with himself. One by one, Sisby candidates shuffle past him, their names ticked off on a list. He looks nobody in the eye.

‘Yes?’ he says to me impatiently, as if I were trying to gatecrash a party.

‘I’m here for the Selection Board.’

‘Name?’

‘Alec Milius.’

He consults the list, ticks me off, gives me a flat plastic security tag.

‘Third floor.’

Ahead of me, loitering in front of a lift, are five other candidates. Very few of them will be SIS. These are the prospective future employees of the Ministry of Agriculture, Social Security, Trade and Industry, Health. The men and women who will be responsible for policy decisions in the governments of the new millennium. They all look impossibly young.